Asif M Basit, London

The Crown – one of the most popular series on Netflix – has now released its fourth season and is receiving great attention globally, thanks to Lady Diana’s entry once again. The series is based on a thoroughly researched script with historians of the royal family – the likes of Robert Lacey – on board.

The opening sequence proudly boasts the claim “based on true events” – a statement that simultaneously justifies the non-sequential order of events to facilitate the drama element.

The series can be called a screenplay of Queen Elizabeth II’s biography. The first season, however, suggests that the whole series rests on a single incident from the life of another monarch: The abdication of King Edward VIII. It is this incident that led to King George VI to accede to the throne and, consequently, for his eldest daughter to inherit it as Elizabeth II.

The Crown, therefore, is a story of the tragedy that befell a young woman of 27 and deprived her of a normal life. Had she been brought up as other heirs-apparent usually are – groomed for their monarchical role from the first day of their life – her coming to throne may not have been as shocking.

For someone third or fourth in line of succession to suddenly become heir-apparent and then go on to actually ascend the throne, is a rare occurrence in modern monarchical history. It is this rare occurrence that suddenly struck the life of Queen Elizabeth II with the abdication of her uncle, King Edward VIII in 1936.

So who was Edward VIII? A prince, a Prince of Wales, an heir to the crown, King of England or, eventually, only a historical figure buried in the grounds (and archives) of Windsor Castle?

Edward Prince of Wales

Prince Edward was officially invested as Prince of Wales on 13 July 1911 by his father King George V. In the years after the First World War, Edward represented the King on a number of goodwill tours of the dominions – visiting India in 1921-22.

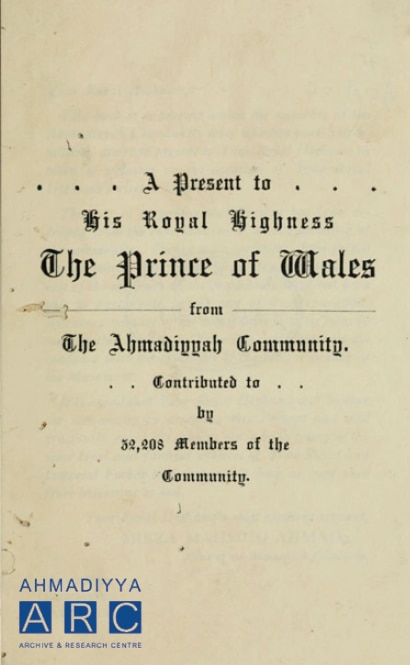

While touring up and down the Indian subcontinent, he would be presented precious gifts from the native rulers and persons of influence, a gift that might not seem precious in the usual sense of the term, was a book written specially for the prince to introduce him to Islam. It was, however, invaluable for the community and its leader who had raised 1 anna (less than a penny) each to have it published.

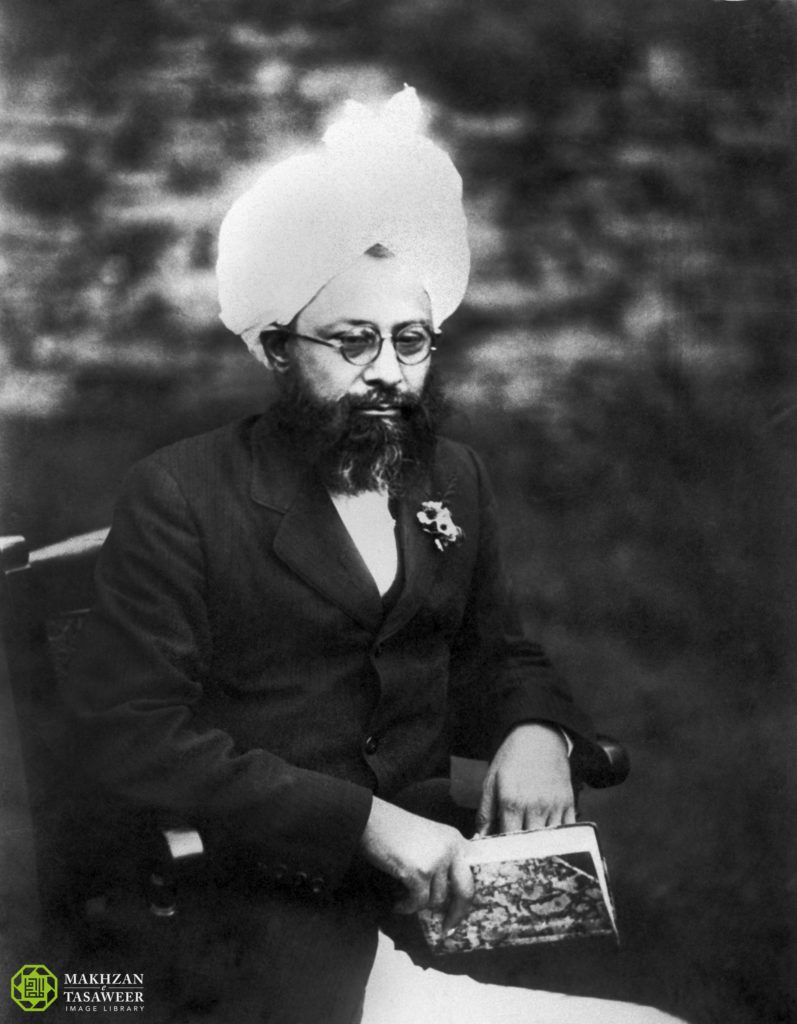

“The cost of preparing this present,” wrote the author, Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmadra, “has been defrayed from the contributions of 32,208 members of the community”. As head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community – a progressive and proselytising sect in Islam – he urged the prince to read it “at least once from beginning to end”. (Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmadra, A Present to His Royal Highness, The Prince of Wales, Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, Qadian, 1922)

The private secretary to the Prince of Wales wrote back that His Royal Highness had “read with interest the account given in the address” and wished to acquaint himself with fuller details of the teachings summarised therein. (Extract from Prince Edward’s Private Secretary, HE Sir Geoffrey deMontmorency’s diary, published in Programmes, Speeches, Addresses, Reports & References in the Press relating to His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales’ Tour in India, 1921-1922, compiled by M O’Nealey, Foreign and Political Department of the Government of India, Delhi, 1923)

British Empire Exhibition 1924

Despite its victory in World War I, the British Empire had suffered great economic setback and felt the need to reassure its colonies that the sun had still not set on it.

As part of a series of such efforts, a British Empire Exhibition was proposed. Edward, the Prince of Wales, agreed to be the president of the organising committee for this exhibition that aimed, as the organisers put it, “to enable all who owe allegiance to the British flag to meet on common ground and learn to know each other”. (British Empire Exhibition [1924]: Incorporated Handbook of General Information, published by the organising committee, London [British Library])

With Prince Edward in the president’s chair, the exhibition acquired royal patronage as well as the support of George Lloyd’s government and hence, the stage was all set. In a grand exhibition of a grand empire – where industry, culture and society of all British colonies were to be depicted – a group of academics felt that religion was an element that needed to be represented too. Spearheaded by the likes of Sir Denison Ross, Francis Younghusband and William Loftus Hare, a suggestion was presented before the organisers that the empire’s religious diversity deserved a fair share.

This was the genesis of the Conference of the Living Religions of the Empire, to which Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmadra was invited – a speaker who travelled the farthest distance to introduce the British people to Islam.

The founder of the Ahmadiyya community – which Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmadra was now the head of – had expressed his desire that such a conference be held in London where delegates from all faiths could introduce their teachings. He had sent this proposal, all the way from India, to the Queen Empress Victoria, in 1899. (Memorial addressed to the Empress of India by Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Tabligh-i-Risalat, published by Qasim Ali, Qadian, 1899)

The proposal saw fruition in the reign of Queen Victoria’s grandson in 1924, with her great-grandson in chair.

The abdication

Who would have known that the young Prince Edward, who was introduced to the message of Islam in India, had a very eventful, yet unfortunate, life lying ahead? After the death of his father, King George V, Edward acceded to the throne as King of England – and naturally back then, the Emperor of India and other dominions – on 20 January 1936. His tenure as Prince of Wales had left the British government suspicious of an ambitious king in the making – something that a constitutional monarch is not supposed to be.

He had addressed the issues of coal miners in South Wales and urged the government to take notice as well as bringing to its attention the rise in unemployment. He ascended, thus, amidst raised eyebrows of not only the government circles but also the Church of England – the two bodies he was to be the figurehead of.

The Church of England had its own problems with Edward VIII. He was seen by the archbishop of Canterbury as a free soul with little or no affiliation with religion. By presenting the royal family – the most respectable family, adored by the majority of the population – as practising, churchgoing, faithful Christians, the church saw a “unique selling point” in the royal household.

His affair – one of many – with an American divorced woman was painted by the church as obnoxiously unorthodox and his intentions to marry her as “sinful”.

Reaction of the Ahmadiyya Press

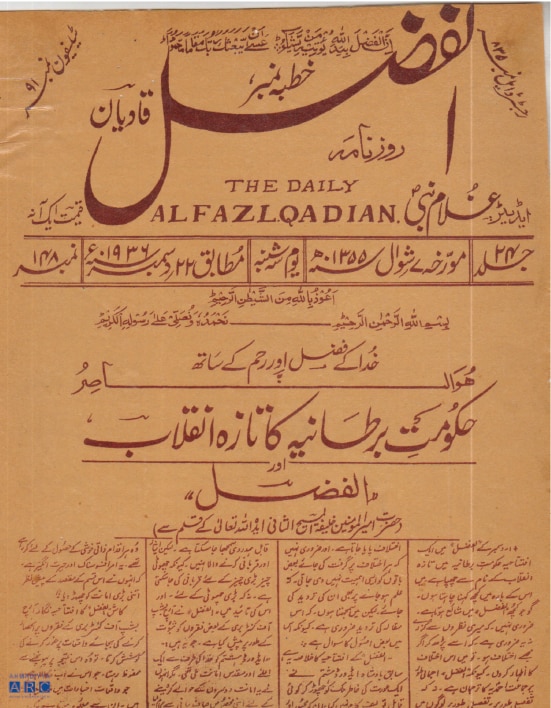

Edward VIII’s abdication made headlines across the world – British and American press in particular and the press of the dominions and India in general. We intend to undertake here a study of the unique response that came from the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in India, through their newspaper, Al Fazl, on 22 December 1936. Titled “The latest revolution in Britain”, the story dealt with the issue in line with the rest of the vernacular press. The approach taken happened to be the opinion that the British government had intended to promote across the empire. Al Fazl too had criticised King Edward VIII for giving precedence to his personal interest over the greater interest of his empire. (Al Fazl, Qadian, 19 December 1936)

This put the pen of Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmadra, then head of the Ahmadiyya community, into action. He wrote a feature article in response to the situation, which got published in the 22 December issue of Al Fazl.

He opened the article by stating that Al Fazl’s immediate and initial response (19 December) was made in haste and that it was influenced by the bigoted opinion of the British government and the Church of England.

He suggested that it was inapt for a newspaper to base their editorial opinion on the content of the archbishop of Canterbury’s speech that had been broadcast on BBC and widely publicised and, in consequence, was heavily relied upon by the press in formulating their opinion.

He quoted the following words from the archbishop of Canterbury’s speech:

“From God, he had received a high and sacred trust. Yet, by his own will, he has abdicated – he has surrendered the trust. With characteristic frankness, he has told us his motive. It was a craving for private happiness.

“Strange and sad it must be that for such a motive, however strongly it pressed upon his heart, he should have disappointed hopes so high, and abandoned a trust great”.

(The part quoted in the original article in Al Fazl, 22 December 1936, is in Urdu. Quoted here is not a translation from Urdu, but the original speech of Cosmo Lang, the archbishop of Canterbury; acquired from the British Library Sound Archives, T8077/0404)

Hazrat Mirza Mahmud Ahmadra urged that instead of relying on the archbishop’s speech, it was essential that the circumstances leading up to the king’s abdication be examined in detail before forming any opinion. Below are some excerpts from his article:

“It is apparent from press reports that:

“1. Mrs Simpson is not new to the royal family. She had been acquainted to George V and has ever since frequented the royal circles.

“2. Edward VIII had not started seeing her recently, but had had a long-time relationship with Mrs Simpson. American press had been speculating for quite some time that she would seek divorce and marry King Edward VIII. She was often invited to royal events where the prime minister too would be present. She stayed in royal palaces and was driven around in royal cars. All this was known to the people of England, just as it was to the prime minister and the archbishop. Th e question is why they decided to stay silent.

“3. Mrs Simpson got her decree of divorce from an English court. The proceedings took place in strict supervision of the police and the press was not allowed to publish a photo of the event … If the British government was unaware of her situation in the palace, then why did it have to exercise such caution?

“4. The king went on a cruise with Mrs Simpson in August. Everyone knew of this yet no condemnation is on record … The prime minister has said in a statement that he had discussed this with the king only in late October … The fact is that everyone who attended royal parties in Mrs Simpson’s presence knew about her [affair] …

“The fact of the matter is that the problem started with a speech of the bishop of Bradford who had expressed that the king should show more inclination towards faith.

“With these words of the bishop of Bradford, the newspapers of North England, followed by the press of the whole of England created a hubbub that the bishop was referring to the king’s affair with Mrs Simpson …

“The bishop of Bradford denied any such reference, but the newspapers kept insisting that the bishop was now lying … But those who are aware of the circumstances know that the bishop had not alluded to the king’s affair with Mrs Simpson but had only indicated that the king should show more association to his Christian faith …

“Thanks to Colonel Wedgwood who stood up during the parliamentary debate and clarified that Mrs Simpson’s affair had come about as a coincidence and that the actual intention of the bishop was only to urge the king to show more affiliation to Christianity.

“Wedgwood went on to say that if the king had expressed his desire not to follow the religious ritual of the coronation ceremony, it was no reason to show antipathy – the coronation is only ceremonial and not a religious assembly – nor should it be a cause of abhorrence if the archbishop or the bishop or York or the prime minister decided not to attend …

“This, added to other happenings, goes to show that the issue of Mrs Simpson was not the actual bone of contention; the actual issue is that when the Coronation Committee met the king and presented the details to him, the king refused to take the religious vows …

“I now want to ask whether the actual issue was the king’s choice between a woman and the monarchy, or was it a matter of choice between monarchy and a matter of principle which meant more for him?

“The church was fearful to have a king – titled the Defender of Faith – who declined to take religious vows. The king, on the other hand, was reluctant in accepting something only for the sake of coming to the throne …

“We cannot say anything for sure about the king’s religious beliefs, but we now know for certain that he chose his principles over the throne.

“I now come to the issue that worked as a basis for the outcome in this conflict … Although the king’s faith was in question, but his decision to abdicate lay on marrying Mrs Simpson. How, then, is this a sacrifice?” (Al Fazl, Qadian, 22 December 1936)

Hazrat Mirza Mahmud Ahmadra went on to show how the question of marriage with a divorcee was, for the Church of England, an issue of faith. He asserts that the church did not object to the moral character of Mrs Simpson, but to the fact that she was twice-divorced and both her ex-husbands were still alive.

The question he raised was that the decree of divorce was issued by an English court under a law passed by parliament; if divorce was such a vicious act, why did parliament pass such a law? And if it is not, then why object to the king marrying a divorcee?

“The former king,” he stated, “had the lawful right to marry. This given, how true is it to say that the king rejected the throne for a woman?”

The article went on to prove that the actual problem, thus, was not whether the king could marry or not, but the fact that if he married, the dominions – especially those with Roman Catholics in majority like Canada and Ireland – would show resentment, leaving the empire in an unstable state. The king’s offer to the government of his morganatic marriage with Mrs Simpson is also discussed in the article, as well as the government’s denial of the proposal.

Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmadra described the king’s predicament as such:

“The king had before him not the people of the country, but a small minority that suggested not marrying a divorcee and, on the other hand, a woman who was ready to marry him and to whom he had pledged to marry …

“The minority’s opinion has no legal standing, whereas the woman in question has the full right to marriage by law. The only way forward for the king was to side with the one who sided with the law …”

The latter part of the article takes a very interesting turn. The episode of Edward VIII’s abdication is linked to Islamic eschatological vision of Christianity, as well as highlighting the Islamic edict on divorce. To quote from the actual text:

“The whole issue is even more important for us and that is what made me write this article. It is in itself a fulfilment of a prophecy of and a means to refute an allegation on the Holy Prophetsa of Islam.

“Prophecy has it that Christianity would automatically melt away in the time of the Promised Messiah; the allegation was that the Holy Prophetsa had permitted divorce and had married divorced women.

“What better proof for the fulfilment of the prophecy could there be when a state that stands for Christianity and more so, whose king is meant to be the ‘Defender of Faith’ denies Christian rites for not having faith in them.

“The world has now come to realise the social importance of divorce and, if not found morally corrupt, a divorced woman’s honour is protected to the extent that a king emperor has forsaken his throne for her …

“Bishops declare victory in this conflict, but Edward’s sacrifice will not go in vain as it is backed by prophecies. There will come a day when England will not only destigmatise divorce, but will also consult Islamic teachings in law-making …

“Only God knows what the religious beliefs of Edward were in his final days as king, but we know from facts surrounding the situation that he was in full or partial disagreement with the religion of the state. Seeing that the church’s establishment was coercing restraint from a matter permissible by law, he must have considered what else they might go on to demand in future …

“The thought process of the church on the other hand seems to revolve around the king’s lack of faith in Christianity. Bishops, in their effort to please their Catholic counterparts in the dominions, saw in it a win-win situation: if they were able to subjugate the king’s opinion, he would forever remain under their thumb; if he chose to abdicate, they would get rid of a king who they saw as standing in their way …

“In short, the conflict was not what is generally understood, but that of faith and the supremacy of law. The king insisted on his personal faith on maintaining the state religion (although a state religion becomes merely politics, especially when it starts to intervene in matters of principle). The king wanted to respect the law and follow it. His opponents thought that the law of divorce was only but a showpiece; the law allowed it, the Church did not.

“Since the king did not approve of Christianity, fully or partially, he decided to side with what satisfied his conscience: the law of land. To save the empire from unrest, he hence gave up his throne.

“Those aware of this detail and the truth behind it tend to cry, ‘Long live Edward, long live!’ “That too is right, but the facts compel me to cry, ‘Long live Muhammad, long live!’” (Al Fazl, Qadian, 22 December 1936)

The above article was written only days after the abdication. Where it surprises one to note how well informed the writer was, it calls for a closer look at the issue at the heart of the abdication conspiracy – the crisis as it brewed in the government and church circles and, even more to one’s surprise, within the royal palace.

Royal family’s concern

To better understand Edward’s personality today, he can be seen as a forerunner of Lady Diana – of a non-monarchical bent, obsessed with public engagement, popular in the general public and devastated through marriage. The Prince of Wales was, as historian Adrian Phillips describes him, “the first member of the royal family to have extensive contact with public in Britain and abroad; he became the first celebrity royal”. (Adrian Phillips, The King Who Had to Go: Edward VIII, Mrs Simpson and the Hidden Politics of the Abdication Crisis, Biteback Publishing, London, 2016)

While it appealed to the general British public, the royal family did not approve of such non-royal behaviour. He appeared to be a “clear contrast to the stern and conservative image of his father” and hence, a “breath of fresh air” (Ibid).

This very factor that earned him a place closer to the public’s hearts left his future precarious in the eyes of his father and the rest of the royal family. Prince Edward openly resented to the way his father wanted him to always dress: formal and complex to carry the air of royalty. Edward on the contrary chose to dress in a way that was closer to general public, albeit to the gentlemen’s class. His father would openly criticise him, even publicly, usually keeping his criticism inconspicuous but also otherwise occasionally. (Philip Ziegler, King Edward VIII, Harper Collins, London, 2012)

The king also despised the men that Edward kept close to himself as friends and associated the prince’s violent habits with such company. Edward’s reproach to a full-time prince was another fundamental bone of contention between him and his father. He desired to play prince when on duty and a private individual in his personal time. This, again, was very un-royal for the household that he belonged to.

His affairs with women, and that too of all sorts, remained a major reason for the king’s concern all through the eventful youth of Edward. George V saw his heir’s casual, illicit and indiscrete affairs as a stigma that could result in loss of popularity of the future king and consequently, of the royal family; he was, after all, to be titled the Defender of Faith when he came to the throne. (Phillips, The King Who Had to Go)

While the modernistic appeal of Edward, Prince of Wales struck a chord with the young and the populace in general, it was seen by the royal family as a danger to the future of the royal family, especially at a time when monarchies were falling left, right and centre. It was essential that the royal family remained aloof, beyond public access and, as they say, “holier than thou”.

The government’s concern

Stanley Baldwin had served two of his prime ministerial terms in the reign of King George V – Prince Edward’s father. He had had cordial relations with the monarch and their correspondence reveals that the king would comfortably share with him what otherwise remained concealed emotions.

Writing to Baldwin on one occasion, King George V expressed his concerns for Edward – his son and heir to the throne – in stating, “After I am dead the boy will ruin himself in twelve months”. (Windham Baldwin Papers, 3/3/14, Cambridge University Library)

Biographers of George V, as well as of Edward VIII, associate the king’s dreads to Edward’s wayward behaviour. For Baldwin, and the government for that matter, it was not the flamboyant, playboy image of Edward that raised dismay and concern.

His ever-growing popularity in the general public – an unprecedented phenomenon for a royal in modern history – paired with his practice of openly voicing his opinion on political matters, is what alarmed Baldwin and his associates; When he comes to throne, what will we have? A constitutional monarch or a king who wants control in political affairs?

Attending a dinner with government dignitaries and foreign diplomats, Edward engaged the Russian ambassador, Ivan Maisky, in a fairly long conversation (Gabriel Gorodetsky [Ed], The Maisky Diaries: Red Ambassador to the Court of St James’s 1932-1943, 15 November 1934) – something very unconventional as a royal is only expected to engage in small talk and that too, limited to pleasantries. As if the prolonged interaction itself was insufficient to leave the establishment and the archbishop of Canterbury to exchange glances in shock, the issues he brought up left them stunned. The content revolved around British diplomacy and that of Germany and France. (Phillips, The King Who Had to Go)

After this dinner in 1934, a chain of similar events kept shovelling more coal to the already ablaze anguish of government circles. Addressing the British Legion, he urged for some members to be sent to Germany by way of extending a hand of friendship and to yield better diplomatic terms (The Times, London, 12 June 1935).

This was taken not only as a royal’s involvement in politics, but also as one that contradicted with the policy of the Foreign Office. Soon after this, Edward was at Berkhamsted School where, in his speech, he criticised the government’s policy of discouraging pupils to train with even light airguns. Anticipating another war, he went so far as to call those in charge of such policies as “misguided people”, adding, “I will even go as far as to call them cranks.” (The Times, London, 13 June 1935)

Enraged, Prime Minister Baldwin brought both the speeches to the table of the cabinet and sought advice. Having agreed that the king should be informed and asked to pull the prince’s reins, minutes of the cabinet’s meeting were forwarded to the palace for the king’s attention. (National Archives, CAB 23/82, 19 June 1935)

Had it been for encroachment in political realms only, the ministers could have pulled certain strings – which we will see that they often did – and got the prince confined to his royal nook. But as his popularity in the general public crept higher, and that too on a steep trajectory, the government was alarmed. What they saw was not a constitutional monarch-tobe, but a president or – as his fondness for Nazi Germany suggested – a Führer in the making.

Edward’s tours across the length and breadth of the Empire earned him a great deal of popularity not only in but beyond the British Isles. “HRH really does work very hard,” reported Admiral Halsey, who had accompanied him on such journeys abroad. Halsey’s letter to Lord Stamfordham goes on to tell how the prince loved to be around common people “especially as he talks to practically every soldier who is bedridden, and his sympathy with them is so genuine that if finds it hard to go on for any length of time” (Phillips, The King Who Had to Go).

This affectionate approach was reciprocated with even more warmth and fervour. By the time he acceded the throne, he was known to be one “too very well known by most of the people of the Kingdom and … very popular with them” (Duke of Connaught to Princess Louise, Royal Archives, RA Vic Add A 17/1590); to be a “genuine solicitude for the unemployed” (Clement Attlee, As it Happened, William Heinemann, London, 1954); one who was with “enormous amount of general knowledge” (Hugo Vickers, Cecil Beaton: An Authorised Biography, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 2020) and who never forgot names and was good at statistics.

But from how the events unfolded, it appears that all this panegyric by politicians and bureaucrats was in fact to mask their dread of a rising revolution. Edward was himself aware of his popularity and of the advantages he had had through his career as Prince of Wales.

“At forty-one I had seen about as much of life as my position had allowed”, the Prince was to write, many years later, in his memoirs.

“The First World War had made it possible for me to share an unparalleled human experience with all manner of men. I had visited practically all the important countries of the world, except Soviet Russia, and many of the smaller ones. I had seen the good and the bad in the Empire, its triumphs and its failures. Princely progresses, diplomatic and commercial missions, not to mention the continuous travelling that I did on my own account, had taken me again and again into realms previously unknown to Royalty.” (Edward, Duke of Windsor, A King’s Story: The Memoirs of HRH the Duke of Windsor KG, Cassell & Company, London, 1951)

Edward went on to boast the titles that he had received through public opinion and had been reflected in the newspapers:

“Britain’s First Ambassador” and “Britain’s Best Salesman”. He held these titles, which acknowledged his services as being above all titles “hereditary or complimentary” ever applied to him. (Ibid)

Edward’s popularity among the general public and his insight of the state machinery and that of the Empire was seen by Westminster and Whitehall as a storm that loomed the horizon. The fear masked under the above pleasantries becomes conspicuous from Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin’s statements to his confidants. One of the three goals that he set for his civil service at the very outset of his term, stated:

“To enable the Prince of Wales (should he succeed to the throne) to make a favourable start as a king”. (National Archives, PREM 1/466)

The very short statement is much sufficient to uncover Baldwin’s doubts and anxieties. The same becomes even more doubtless when Baldwin describes the king as “an abnormal being, half childish, half-genius … It is almost as though two or three cells in his brain had remained entirely undeveloped while the rest of him is a mature man.” (Baldwin Papers f418, University of Cambridge Library, The Royal Box)

Then there are accounts of the private secretary of the Prince of Wales, Allan Lascelles confiding in Baldwin and listing the Prince’s defects. Lascelles bitterly resented the Prince’s “drinking, womanising and pursuit of selfish pleasure” and doubted if he was fit for his future role as king.

Protocols were not only breached by Lascelles in directly approaching the prime minister, but by Baldwin also in entertaining the grievances of a royal’s private secretary. Lascelles’ despise for the Prince was even bolder when he told the prime minister that “the best thing that could happen to [the prince], and the country, would be for him to break his neck”.

Even bolder was Baldwin’s endorsement:

“God forgive me, I have often thought the same.” (Duff Hart-Davis [Ed], King’s Counsellor: Abdication and War: The Diaries of ‘Tommy’ Lascelles, Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London, 2006)

With these deep-seated loathsome anxieties for King Edward VIII, from the time he was next in line to the throne, Baldwin’s role surfaces even more when he collaborates with the Church in conspiring to bring the king down; to this we will return later.

The Church of England’s concerns

Lambeth Palace seems to have remained indifferent of Prince Edward’s womanising and other wayward characteristics. What seems to have concerned them most is his lack of religious affiliation, which, in view of his public popularity, could weaken the grip of the church on state affairs. He was known to be non-practising, but that he had drifted even farther away from Anglican beliefs became apparent with his ascension.

Edward VIII’s official biographer, Philip Ziegler, notes that “even if there had been no Mrs Simpson, a clash between the King and the Establishment was inevitable.” Explaining his stance further, Ziegler explains that the Establishment had deep-rooted traditions and that to shake these roots was bound to come with lethal results for a constitutional monarch.

“Edward VIII recognized,” he says, “that he would be offending vested interests and injuring people who felt that they deserved better of him, but he was a strong proponent of the view that omelettes are only made by breaking eggs.” (Ziegler, King Edward VIII)

Edward VIII’s characterisation by HG Wells is worthy of note:

“He betrays the possession of a highly modernized mind by his every act, he is unceremonious, he is unconventional, and he asks the most disconcerting questions about social conditions …” (Baltimore News Post, 9 December 1936)

The Church of England would naturally be far from comfortable with a king who had “an enquiring mind, was disinclined to accept dogma as invariably correct, grew impatient if told that something could not be done because it had never been done before”. (Ziegler, King Edward VIII)

With such a figure on the throne, Cosmo Lang, the Archbishop of Canterbury, decided to personally, but discretely, intervene. With his shrewd intellect, he was to be instrumental in the abdication, yet maintain his image of being aloof from the politics that was to rampage the Crown.

It is not hard to imagine what the Archbishop would have felt when his principal adviser, Alan Don, reported to him that the new King intended to turn Roman Catholic to “escape from his unwelcome task”. “This was told to me,” he wrote in his diary, “by as Diocesan Bishop who had just been talking to an ex-Cabinet Minister”. (Alan C Don’s diaries, Lambeth Palace Library, MS 2864, 19 February 1936)

While Don’s above statement came as a reminder at the outset of Edward VIII’s reign, his reproach for Anglican faith was quite commonly known from many years before. He himself admitted to not being versed with the “Protestant faith, of which, by virtue of my birth, I was destined one day to be the ‘Defender’”. (Edward, A King’s Story)

During his early days on the throne, Edward VIII was swamped in conflicting emotions. That he expressed them added fuel to the fire of anxiety already giving sleepless nights to the Archbishop. The King knew that the popular opinion of his subjects saw him as progressive and had invested in him their hopes for change.

“It became increasingly plain to me,” he recalled later, “… that however wholeheartedly I might adapt myself to the familiar outward pattern of kingship … I could never expect wholly to satisfy the expectations of those for whom the rigid modes of my father’s era had come to exemplify the only admissible standard for a King … But I was also acutely conscious of the changes working in the times, and I was eager to respond to them as I had always done.” (Ibid)

The King was in this conflicting state of mind when the Archbishop had his first audience. It was on the day after George V died. This first meeting struck the wrong chord for both these stalwarts of the Church of England. Cosmo Lang, the Archbishop, recorded the meeting in his chronicle:

“… I had quite a long talk with the King. I told him frankly that I was aware that he had been set against me by knowing that his father had often discussed his affairs with me … He did not seem to resent this frankness, but quickly said that of course there had always been difficulties between the Sovereign and his heir.” (Cosmo Lang Papers, Lambeth Palace Library, Vol. 223)

The King’s account on this meeting matches Lang’s account but also captures the negativity that this meeting had sown in their relationship.

“No man likes to be told,” the King wrote, “that his conduct has provided a topic of conversation between his father and a third person. At any rate the Archbishop’s disclosure was an unpropitious note with which to inaugurate the formal relations between a new sovereign and his Primate.” (Edward, A King’s Story)

Lang’s account also confirms that the meeting had left a somewhat bad taste: “It was clear that he knows little, and I fear, cares little, about the Church and its affairs.” (Lang Papers, Lambeth Palace Library, Vol. 223)

The King concluded his recollection of the meeting in saying, “That encounter was my first intimation that I might be approaching an irreconcilable conflict”. (Edward, A King’s Story)

Lang proactively maintained an active connection with anyone who could bring him ammunition for his battle against a king that he desired not to stay on the throne. Disgruntled staff from the palace – mostly for being sacked or demoted by King Edward – would approach Lang to further nourish his ambitions against the King.

Just as Lascelles had confided in Baldwin, Admiral Lionel Halsey is reported to have headed straight to Lambeth Palace as soon as he was told by the King that he was no longer required on the household staff.

Halsey continued to visit Lang and write to him, originals of which are archived in the Lambeth Palace Library. He had been Edward VIII’s private secretary, replaced soon by Wigham. Halsey’s letters to Lang contained information acquired from Wigham which only go to show the King’s own staff’s disloyalty to him but loyalty to the establishment.

Halsey’s letters also indicate that Wigham had been providing information about the King to Baldwin. That the Viceroy of India, Lord Linlithgow, discussed the situation with both Baldwin and Lang during a visit to London, reveals that the Establishment had taken the dominions on board their malicious intents; Baldwin and Lang knew very well that dominions will have to play their part when the time came.

Very soon after Edward VIII’s ascension to the throne, the government and the Church of England – notoriously known as the Establishment – had joined hands in their conspiracy against a King who did not suit their agenda. The King himself was generous in providing the Establishment with stories to further stack their growing piles.

Breaking away from his father’s practice, he refused to subscribe to ecclesiastical charities right at the start of his reign. Chaplains of the Archbishop brought to his knowledge that the King did not attended the Chapel Royal – confirming doubts that he had no interest in Christian faith. (Diaries and Papers of Rev Alan C Don, Lambeth Palace Library, under various dates of March 1936)

Such a petty observation that the “king had also fidgeted all through the Royal Maundy Service” was important enough a piece of information as to be worthy of reporting to the Archbishop. (Ibid)

Launcelot Percival, who had been the precentor at the Chapel Royal for 14 years when Edward VIII acceded to the throne, would report every action of the King to Archbishop Lang; that the King and Mrs Simpson stayed out late at night and that the King laid expensive gifts at the feet of his mistress are some of the issues on record that he conveyed to Lang. Trivial they might seem, but that even such issues reached the Archbishop reveals a lot about the gravity of the conspiracy.

A collection of cuttings from the American press – that had remained vocal about the Edward/Simpson affair – held at Lambeth Palace archives points to the level of interest that the Archbishop had in the situation; that letters with these cuttings were addressed directly to him tells even more. Adding insult to injury was Edward VIII’s disinclination to consult the Archbishop who had, during all his career, been consulted in every matter by George V.

How the Church would hold the monarch under its thumb seems to have become a matter of greater concern for Archbishop Lang. Baldwin and his government also faced the same predicament. It would not be wrong to conclude that it was at this crossroads that their paths crossed and it was here that the Church and the Government united in their efforts to topple their own King. It was here that they might have continued to sing “Long live the King!” – hand on heart – quite contrary to their actions.

The Church and government against the King

The Establishment – which here means the Church and the Government combined – now united and turned all guns in the King’s direction; even though the king is meant to be the third pillar of the establishment.

By this point, the American press had gained significant momentum about the King’s affair with Mrs Simpson. It was at this point that the Establishment unbolted and flung open the sluice that had so far been holding the British press at bay.

Confidential meetings with Geoffrey Dawson, Editor of The Times, with Archbishop Lang, and their correspondence – both on record and held at the Lambeth Palace Library and Bodleian Library, Oxford University – speak volumes about how all major state institutions had their strings tied to the Archbishop’s fingers.

The Archbishop recorded this meeting with Dawson in his diary:

“I had a long and very confidential talk with him in which he spoke to me about the possibility at some early date of The Times intervening in an article”.

The Archbishop was so thankful for his support that he wrote to Dawson the next day (12 November 1936). Half of the letter has been torn off but the remaining sits in the shelves of Lambeth Palace Library:

“I need not tell you how grateful I was to you for our confidential talk yesterday. Since I saw you I have talked to other responsible people and it becomes increasingly apparent that some decisive clearing of the air must be achieved within the shortest possible time. I only hope that the Prime Minister will now take some further definite step.” (Cosmo Lang Papers, Lambeth Palace Library, Vol. 129)

Although the letter does not reveal who these “other responsible people” were, but since Baldwin has been mentioned, it only goes to mean that the Archbishop had all instruments of the Empire’s machinery under his thumb. Dawson had also been to see Prime Minister Baldwin and had found him equally concerned about the situation. (Geoffrey Dawson Papers, Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, Vol. 55)

The Establishment let the British press off the lead and newspapers, especially tabloids, were soon buzzing with sensational stories. As Hazrat Mirza Mahmud Ahmadra had rightly assumed, the Establishment had Mrs Simpson’s story ready as their scapegoat.

The Archbishop had carefully engineered the search for a sacrificial lamb and had finally managed to find a femme fatale. A letter of his, written after the storm of abdication had settled, is quite indicative of his approach:

“… as the months passed and his relations with Mrs Simpson became more notorious the thought of my having to consecrate him as King weighed on me as a heavy burden.” (Cosmo Lang Papers, Lambeth Place Library, Vol. 223)

“Think of pouring all those sacred words into a vacuum” is a remark that Archbishop Lang made to one of his confidants. Not only is his intention to not let the King make it as far as his coronation evident, but even more striking is this intention’s similarity to that of Baldwin’s – “should he succeed to the throne”. (Ibid, Vol. 318)

Archbishop Lang took his Bishops in confidence before moving on to the big step. He invited them all to his room “of which windows were fast closed, and the atmosphere stifling”, as Herbert Henson, one of his bishops, later described. No minutes of this in-camera meeting were taken but Bishop Henson’s diary holds most of the secrets discussed. He recalls the Archbishop briefing them about the coronation:

“It would not be edifying to stir up the nation to a religious preparation for the King’s crowning when the King himself was making it apparent that he himself took anything but a religious view of the ceremony.” (Bishop Henson Papers, Durham Cathedral Library, under 17 November 1936)

This statement of Lang’s refers to the King’s intention to dismiss the Christian vows that have remained at the heart of a British monarch’s coronation. Soon after Edward VIII’s ascension to the throne, during a meeting to map out coronation plans, Archbishop Lang “had to defend the importance of the Christian ritual involved in the coronation service when challenged by sovereign who wanted to scale back what he perceived as humbuggery of royal ceremonial”. (Edward Owens, The Family Firm: Monarchy, Mass Media and the British Public 1932-53, University of London Press)

It is concluded by most historians and biographers that the above was “just one example in a catalogue of offences” compiled by Archbishop Lang against Edward and one that compelled him to pave the way to topple a king with a modernising agenda; an agenda that did not suit the Church of England and, for that matter, the status quo. (Ibid)

Edward VIII seems to have tried all possible ways to exercise his lawful rights as well as stay on the throne. Although he thought that he could lawfully marry Mrs Simpson, he was flexible enough to respect the sentiments of the Establishment by proposing a morganatic marriage with Mrs Simpson.

This meant that Mrs Simpson would legally be the King’s wife, but would not be titled the Queen-consort, nor would their children from the marriage be placed in the line of succession to the crown. This too was rejected by Baldwin who, as is now quite obvious, was not acting alone.

Archbishop Lang wanted to see the King’s removal from the throne “as soon as possible”, an intention that he had quite plainly expressed in a letter to Baldwin – in an envelope marked “Strictly Private”. (Stanley Baldwin Papers, Cambridge University Library, Vol. 176, 25 Nov 1936)

The letter concluded with these words:

“Only the pressure of our common anxiety – and hope – can justify this letter”. (Ibid)

Not everyone in the Parliament was an ally of Baldwin and his cabinet. There were ministers, including the likes of Winston Churchill, who had a soft corner and sympathy for the king. (Montgomery Hyde, Baldwin, the Unexpected Prime Minister, Hart-Davies, MacGibbon, London, 1973)

Although The Times was hijacked by the Establishment, the popular press continuously expressed allegiance to the king. The public did not want their king to go and that too for a matter that they saw as a trivial one. It was beginning to seem highly likely that there could form a “King’s Party” in the Parliament. This is something that Edward VIII did not desire for his country and the Empire. He could not bear the bifurcation of the nation on an issue of so personal a nature.

On the dull evening of 2 December 1936, Prime Minister Baldwin headed to the Palace to see the King to tell him that it was now a matter of urgency and that the decision must now be made. He presented the King with three options:

- To give up Mrs Simpson

- The morganatic marriage option (which was by then an invalid option)

- Abdication

(Cosmo Lang Papers, Vol. 318, Lambeth Palace Library)

Baldwin, as a matter of fact, knew that the King was now only left with the third choice to opt for. He reported the details of his audience back to Lang the next day. Through a very opportunistic move, they thought that they had finally toppled the King. And they were right.

Edward VIII, seeing that he would not be allowed by the Establishment to remain on the throne, decided to abdicate. He signed his abdication notices on 10 December and announced it to the public through a radio broadcast on 11 December 1936.

Braggers of “freedom of speech”

Going through the archives and records of this crisis, one is shocked to notice how the King was cornered and pinned down by the British Establishment. Edward VIII, with the intention to know how his subjects saw the whole situation, expressed his desire to address the nation through a radio broadcast. Edward VIII later recalled:

“I thrust at once to the point of the meeting, the project of the broadcast. The idea seemed to startle him and, if I correctly read his thoughts, he seemed to be saying to himself rather irritably, ‘Damn it; what will this young man be thinking up next?’” (Edward, A King’s Story)

He was absolutely right in reading Baldwin’s mind. Baldwin took the proposal to the cabinet and came back to tell the King that the proposal had been rejected. (Baldwin Papers, Vol. 176)

In their dread of a monarch who could challenge the status quo, the Establishment denied him the right to even address his people. Thrown out was the fact that he was still the King; ignored were the crowds outside the palace who sang “Long live the King!” and “For he’s a jolly good fellow” in showing their support for their King; brutally disregarded was the notion of “freedom of speech” that the British Government was, and is, very proud of.

Archbishop Lang was, however, allowed to broadcast his message to the nation a few days after the abdication. Having observed that the public opinion was bewildered (Lang Papers, Lambeth Palace Library, Vol. 318), he broadcast his address on radio.

Lang’s biographer, Robert Beaken, is rightly of the opinion that the Archbishop’s voice sounded “nervous in comparison with other recordings”. (Robert Beaken, Cosmo Lang: Archbishop in War and Crisis, IB Tauris, London, 2012)

It was this speech that Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmadra had referred to in his Al Fazl article – only having read excerpts and with no access to the audio. Robert Beaken’s observation is absolutely correct, which can be confirmed by listening to the speech preserved at the British Library. (British Library, Sound Archives, T8077/0404)

Lang’s close confidant, Alan Don, recorded in his diary how the Archbishop was found kneeling in prayer beside his desk just before leaving for the broadcast. (Don Diaries, Lambeth Palace Library, under 15 December 1936)

Don also noted down his own impressions about the address:

“I am a little apprehensive about it, for I think it may have the effect of confirming suspicion … that he had engineered the whole thing”. (Ibid)

Conclusion

It is incredibly amazing to note how a man in a small town of the Punjab – thousands of miles away from the hubbub of the abdication crisis – could so minutely understand the facts behind the fictional presentation of the story.

How right was Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmadra in asserting that the King’s abdication to protect his lawful right to remarry a divorcee would set up a legacy – a legacy of allowing, along the Islamic lines, to divorce when inevitable and to remarry when divorced.

There is no need to delve into how members of the Royal Family have ever since been able to divorce and to remarry of their own freewill. There are many! (And counting, it seems!)

Despite the flamboyant claims of being secular, are the so-called modern Western governments still puppets of the church? This too is not the scope of this article. Does the church still try to control state affairs or is that now a bygone? Or is it that the church’s establishment in the West is more skilled at the cunning art of keeping their interventions discreet (as opposed to the clergy pressure groups of the Muslim East)?

The answers are still hazy. We may find out in another few decades.

This is extremely interesting. I had no idea Hazrat Musleh-e-Maud had such a deep insight into this matter. Inshallah, looking forward to the next part.