Romaan M Basit, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre

For most Muslims, hearing the word “caliphate” is an instant reminder of a golden age in Islam – a time when the entire ummah was united and strong under one leader, the caliph, after the demise of Prophet Muhammadsa. But today, this idea feels more like a nostalgic fascination than reality. Sectarianism has reached unprecedented levels and has been exacerbated by underlying political motivations. In the face of this sect-centric approach towards Islam, the dream of a single Muslim caliphate seems almost unthinkable.

This article attempts to make the case that establishing the caliphate is not merely an optimistic idea that might one day happen, but rather a compulsory religious obligation which Muslims must fulfil. The duty of establishing a caliphate is – and has always been – known as a fard kifaya (communal obligation) in Islamic law. According to the Quran, Hadith, and centuries of Islamic scholarship, if this obligation is not fulfilled by some in the community, the entire ummah remains in a state of sin. The consequences are too severe to ignore.

Furthermore, a caliph can only be elected and appointed by a council of qualified leaders and scholars known in the tradition as the ahl al-hall wa al-aqd. This body of people must first be elected before the caliph can be chosen. The issue is, however, that in today’s divided ummah, even agreeing on who should be part of such a council is close to impossible, let alone choosing a caliph accepted by all.

So, can such an important obligation ever be materialised? If not, then should the ummah continue to live, as Islamic jurists suggest, in the state of a collective sin? These and other such questions form the basis for this research.

Caliphate in Islamic discourse

The station of caliphate holds great significance in Islam. After the demise of Prophet Muhammadsa in 632 CE, Islamic leadership continued in what is accepted by the Muslim majority as the “rightly guided caliphate” (khilafa rashida), which lasted for approximately thirty years. Following this period, the leadership, whilst still holding on to the title of caliphate, gradually faded into despotism and monarchy. Prophet Muhammadsa had prophesied this exact series of events in clear words; and, in the same hadith, he also mentioned that a true caliphate would once again be established “on the precepts (minhaj) of prophethood.” After saying this, he remained silent, marking the end of the hadith.1

This prophecy of a caliphate “on the precepts of prophethood” has been a subject of interpretation throughout Islamic history. One early example involves the eighth Umayyad caliph, Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz (d. 720). Upon assuming office in 717, he received a letter from Habib ibn Salim (d. 720), one of the narrators of the aforementioned hadith. Ibn Salim wrote that, in his opinion, the “caliphate on the precepts of prophethood” prophecy had been fulfilled when Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz became the caliph.2

However, if we take the Prophet’s truthfulness and the reliability of the above-mentioned hadith as a basis, this theory cannot hold true, since neither of the two distinctly mentioned periods of kingships had yet come to pass. This view has also been expressed by modern Salafi hadith scholar al-Albani (d. 1999):

“It seems far-fetched to me to apply this hadith to Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz, because his caliphate was close to the era of the rightly guided caliphate, and there had not yet existed two kingdoms: a mordacious kingship (mulk add) and a coercive kingship (mulk jabariyya), and Allah knows best.”3

Another interpretation of this hadith by some scholars is that such a caliphate would only be established after the appearance of the Imam Mahdi in the latter days. Two contemporary scholars of this view are Amin Muhammad Jamal ad-Din,4 a professor at al-Azhar University, and Syrian scholar Muhammad al-Yaqoubi.5 The Ahmadiyya Muslim school of thought also presents this interpretation as evidence of the legitimacy of its caliphate.

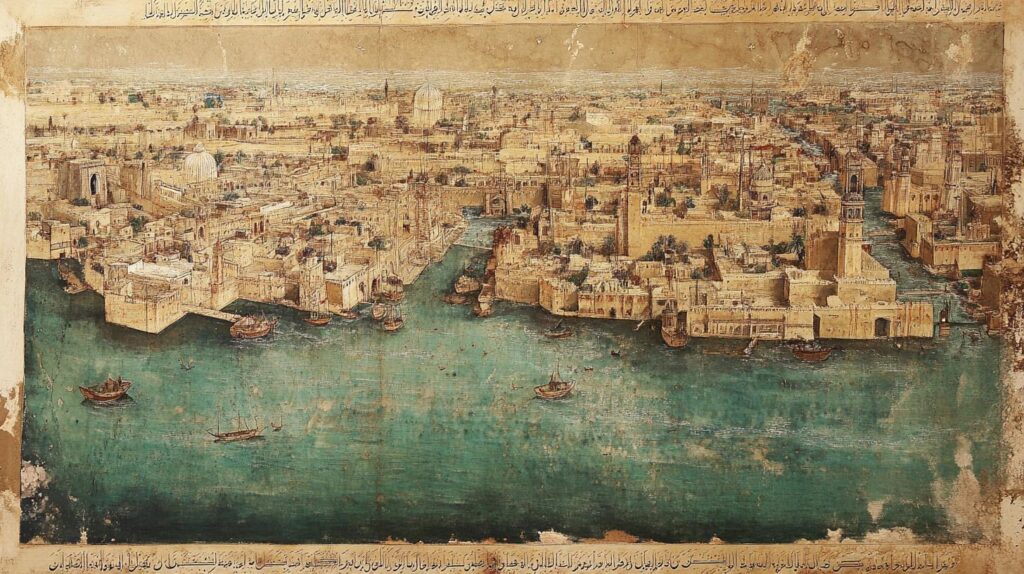

From the election of Abu Bakrra in 632 until the collapse of the self-proclaimed Ottoman Caliphate in 1924, there have consistently been different manifestations and attempts to establish a caliphate, some more questionable than others.

In the present day, a formal system of caliphate can be found in the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, which has been functioning since 1908. Although there has been controversy surrounding whether this is a legitimate caliphate or not, this has been the case with all caliphates in Islamic history. Even the rightly guided caliphate, which is accepted, revered and renowned by the majority of Muslims around the world, was not free from the question of legitimacy.

The first three rashidun caliphs are rejected by a large group of Muslims, namely the Shia. Every caliphate has faced intense scrutiny and ultimately been rejected by some Muslims; therefore, mere scrutiny is not a basis for rejection.

In any case, the idea of a caliphate being re-established is prevalent in Islamic discourse and not an alien concept. There are, however, contentions and differences of opinion about the very definition of a caliphate and how it will be manifested: the roles a caliph should carry out, the qualities he should possess, and the prerequisites required to establish a caliphate in the first place. These are just some of the questions that scholars of every era have had to grapple with. Still, the importance and necessity of establishing one has been almost unanimously agreed upon and emphasised through the ages.

Caliphate has been described as “a pillar from the pillars of religion (din)” by the Maliki exegete al-Qurtubi (d. 1273), as “one of the greatest obligations of the din” by the proto-Salafi reformer Ibn Taymiyya (d. 1328), and “from the necessities of the Shari‘a that simply cannot be left” by the Shafi‘i jurist and mystic al-Ghazali (d. 1111).6

The technical term commonly used for this obligation is fard kifaya, which translates to communal obligation or obligation of sufficiency. It entails that until some people from within the community fulfil the obligation, the entire Muslim ummah collectively bears the burden of the sin of noncompliance. The specific group within the community tasked with fulfilling this obligation in the case of the caliphate is known as ahl al-hall wa al-aqd (lit., “those who loosen and bind,” referring to those with the authority to make decisions on behalf of the community). Further still, the death of any Muslim who dies whilst the fard kifaya has not been fulfilled may be classed as a “death of jahiliyya (ignorance)” – as per a hadith of Prophet Muhammadsa.7 This concept will be explored at length.

Before exploring the scriptural and scholarly arguments for this obligation, it is essential to clarify what is meant by the term “caliphate,” as it has been used in various ways throughout Islamic history.

Defining different types of caliphate

Broadly speaking, there are many different types of caliphate in Islamic discourse. Among them, the two major ones we find in the Quran and Hadith are “Caliph of God” (Khalifat Allah) and “Caliph of the Prophet” (Khalifat al-Rasul). The word khalifa in Arabic refers to a successor, deputy, or vicegerent – someone who takes over after another, acting on their behalf or continuing their mission.

Prophets are caliphs of God, which we know from the verses in which Prophets Adam and David have been called caliphs.8 In a similar manner, Prophet Muhammadsa also came as a prophet of God to purify mankind and teach the book (i.e., the Holy Quran) and wisdom. This was the primary objective of Prophet Muhammadsa as defined by the Holy Quran,9 as well as that of all prophets.10

To understand this concept further in simpler terms, if someone is a tailor, the person doing the same work after him is his khalifa. If a student takes up the task of conducting a class in the absence of his teacher, that student will be called the khalifa of the teacher. Likewise, the one who succeeds the work of a prophet is a khalifa of that prophet. Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra explains this in his book Barakat-e-Khilafat (Blessings of Khilafat).11

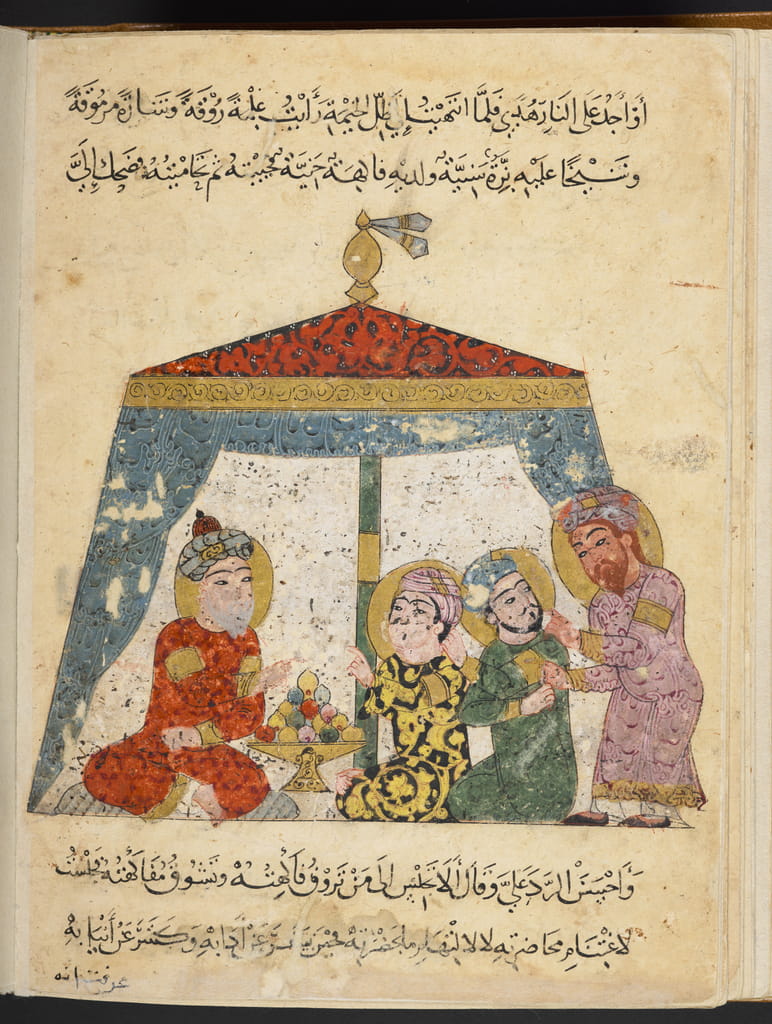

There was a degree of confusion after the demise of Prophet Muhammadsa as to who would take on the mantle of leadership and continue the prophetic mission. Within a day, Abu Bakrra was agreed upon as a suitable candidate by the companions and elected as the first khalifa of the Prophet.

The rashidun period ended abruptly with the assassination of Ali (d. 661), bringing the thirty years of caliphate prophesied by Prophet Muhammadsa to an end. After this period, “caliphate” was still used as a title, but had become more of a worldly kingship in essence, as had been prophesied. Hanafi scholar al-Taftazani (d. 1390) mentions that after Ali’s passing, “Muawiyah and those who came after him would not have been [rightful] caliphs, but rather mere kings and rulers.”12 His evidence was the hadith in which Prophet Muhammadsa said the rightful caliphate would continue after him for thirty years.

Synonymity of imamate and caliphate

Before proceeding, it is essential to clarify the relationship between the terms “caliph” and “imam,” and “caliphate” and “imamate,” since they are often used synonymously and interchangeably in this specific context.

Not only has this been allowed by scholars of the past, but it has also been a norm. Al-Nawawi (d. 1277 CE), the eminent Shafi‘i jurist and Hadith scholar, is one of the many scholars who have explained this. He writes:

“It is permitted to call the imam: The caliph, the imam or the leader of the believers (amir al-mu’minin).”13

What may cause confusion, however, is that there are two types of imamate: al-imama al-sughra (the lesser imamate) and al-imama al-kubra (the greater imamate, also known as al-imama al-uzma). The term caliphate has been, throughout history, synonymous with al-imama al-kubra, which is a specific type of imamate, not a general one.

The first type of imamate, which is general and known as al-imama al-sughra, has been described in al-Mawsu‘a al-Fiqhiyya al-Kuwaytiyya (The Kuwaiti Encyclopaedia of Islamic Jurisprudence) in the following way:

“Any leader who is followed by a people, whether they are on the straight path, as in where Allah says in the Quran: ‘And We made them leaders guiding by Our command,’ or they are misguided, as in His saying: ‘And We made them leaders who invite to the Fire, and on the Day of Judgment they will not be helped.’

“Then, the term expanded in its usage, and it came to refer to anyone who became a model or leader in a particular field of knowledge. For example, Imam Abu Hanifa is a model in jurisprudence, and Imam al-Bukhari is a model in Hadith.

“However, when the term is used without any qualification, it specifically refers to the one who holds the greatest leadership position, and it is only applied to others with an addition, such as ‘imam of a particular field.’ Therefore, al-Razi (d. 1210) defined an imam as: ‘Any person who is followed in religion.’”14

Al-imama al-kubra, however, is different and specific in its usage. It has been explained to be:

“The Grand Leadership (al-imama al-kubra) terminologically refers to a leadership in both religion and worldly matters, as a caliphate succeeding the Prophet. It is called ‘great’ (kubra) to distinguish it from the lesser leadership (al-imam al-sughra), which is the leadership of prayer. Its place and position are to be considered.”15

In the encyclopaedia entry, under words which are connected or related, the term khilafa has been mentioned:

“The verbal noun khilafa is derived from khalafa (to succeed, to come after), meaning: to remain after someone or to take their place. Anyone who succeeds another person is called a khalifa. Therefore, the one who succeeds the Messenger of Allah in executing the religious rulings and leading the Muslims in religious and worldly matters is called a khalifa. The position is referred to as khilafa or imama (leadership).

“As for the jurisprudential (shar‘i) definition: It is synonymous with imama. Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406) defined it as: ‘It is the responsibility of guiding the entire community according to the religious perspective, in matters that pertain to their spiritual and worldly interests.’”16

Having established these broad categories, we can now turn to the scriptural evidence to understand the basis for the obligation of establishing a caliphate, specifically one that fulfils the prophetic promise of being “on the precepts of prophethood.”

Scriptural evidence of the caliphate being an obligation (fard)

– The Holy Quran

The obligation of establishing the caliphate can first and foremost be established from the Holy Quran, which Muslims unanimously believe is the unaltered word of Allah. In Islamic jurisprudence, when it comes to rulings, the Quran takes precedence over all other sources, such as Hadith and the consensus of scholars.

A conversation between Allah and the angels is found in Surah al-Baqarah in which the placing of a khalifa on earth is mentioned:

“And when thy Lord said to the angels: ‘I am about to place a vicegerent in the earth,’ they said: ‘Wilt Thou place therein such as will cause disorder in it, and shed blood? — and we glorify Thee with Thy praise and extol Thy holiness.’ He answered: ‘I know what you know not.’”17

Al-Qurtubi (d. 1273), the Andalusi-Maliki scholar and polymath better known for his tafsir, derives the obligation from this verse:

“This verse is sound evidence for having a leader and a caliph who is obeyed so that he will be a focus for the cohesion of society and the rulings of the caliphate will be carried out. None of the Imams of the Community disagree about the obligatory nature of having such a leader, except for what is related from al-Asamm [lit. the Deaf], who lived up to the meaning of his name and was indeed deaf to the Shari‘ah, and those who take his position who say that the Caliphate is merely permitted rather than mandatory if the Community undertakes all their obligations on their own without the need for a ruler to enforce them. Our evidence is found in the words of Allah Almighty: ‘I am putting a caliph on the earth’ as well as other verses (38:26, 24:55).

“All of this indicates that it [caliphate] is obligatory and is a pillar from the pillars of the din.”18

The scholar in question, Abd al-Rahman ibn Kaysan known as al-Asamm (d. 816), was a Mu‘tazili who lived in Basra and did not consider appointing a caliph to be an obligation. Al-Juwayni (d. 1085), the prominent Shafi‘i jurist and Ash‘ari theologian, has also classed him a deviant for holding this opinion and said that he is preceded by a consensus of all scholars who opposed his view, affirming that it is indeed an obligation.19

In the mentioned passage, al-Qurtubi refers to verse 56 in Surah an-Nur as further evidence of the obligation, in which Allah promises the believers that He will establish a caliphate:

“Allah has promised to those among you who believe and do good works that He will surely make them Successors in the earth, as He made Successors from among those who were before them; and that He will surely establish for them their religion which He has chosen for them; and that He will surely give them in exchange security and peace after their fear: They will worship Me, and they will not associate anything with Me. Then whoso is ungrateful after that, they will be the rebellious.”

– The Hadith corpus

Evidence is also found in the Hadith corpus. Prophet Muhammadsa is reported to have said that the one who dies without the oath of allegiance on his neck dies a death of jahiliyya (generally translated as ignorance, but more precisely means the pre-Islamic state, i.e., non-Islamic state, in this case), and, in another variation, it says that the one who dies without recognising the imam of his age dies a death of jahiliyya.20

Scholars have relied on this hadith as evidence for the caliphate being an obligation. This hadith also resolves a side issue: when a caliph is elected, the pledge of allegiance must be given to him.

Al-Shawkani (d. 1834) was a prominent Sunni scholar who specialised in many areas, including tafsir, Hadith and jurisprudence. He is seen as an influential and authoritative proponent of the Athari creed and a key scholar of the reformist Salafi movement. He uses this hadith as evidence and also attributes it to Ahmad ibn Hanbal (d. 855), at-Tirmidhi (d. 892), Ibn Khuzayma (d. 923) and Ibn Hibban (d. 965), among others:

“From the strongest evidence for the obligation of appointing an imam and pledging allegiance to him is what Ahmad [ibn Hanbal], al-Tirmidhi, Ibn Khuzayma, and Ibn Hibban in his sahih, extracted of the hadith of al-Harith al-Ash’ari in the wording (that the Prophetsa said), ‘Whosoever dies whilst not having over him an imam of the jama’a, then indeed his death is the death of jahilliya.’ Al-Hakim also narrated it from Ibn ‘Umar and Mu‘awiya and al-Bazzar narrated it from Ibn Abbas.”21

A question arises here as to what dying a death of jahiliyya actually means and entails. Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani (d. 1449), in his magnum opus Fath al-Bari – a distinguished commentary on Sahih al-Bukhari – has elaborated on the meaning of this phrase:

“What is meant by ‘dying a jahili death’ […] is dying a misguided death like those in the jahiliyya times who did not have a just and obedient imam as they had no concept of that. It does not mean that a person dies a disbeliever – rather he dies as a disobedient person.”22

It can be ascertained that the one who dies without pledging allegiance to a caliph dies a death of disobedience, which would be sinful. To pledge allegiance, a caliphate must first be present.

Al-Taftazani explains that Muslims who live in a time in which a caliph has not been elected fall into disobedience and, by extension, die the death of jahiliyya. In his understanding, there was no true, rightful caliph after the rashidun period:

“After the rightly guided caliphs, the [Muslim] ummah remained without an imam, so the entire community fell into disobedience, and their death was akin to the death of ignorance (jahiliyya).”23

He also states that there is a consensus (ijma‘) on this issue:

“There is (scholarly) consensus on the appointment of an imam being obligatory. The difference of opinion is only on the question of whether the obligation is on Allah or man, and whether is it by textual or rational evidence. The correct position is that it is obligatory upon man by the text, due to his saying, ‘Whosoever dies not knowing the imam of his time dies the death of jahiliyya’, and because the ummah (i.e., the companions) made the appointing of the imam the most concerning of important matters after the death of the Prophet to the extent that they gave it priority over the burial; similarly after the death of every imam, and also because many of the other shari‘a obligations depend upon it.”24

Hanafi scholar Abu Shakur as-Salimi (d. 1066) also uses the hadith to argue in favour of the obligation and that it is a matter of consensus amongst the scholars of the ummah:

“Know that the caliphate is an established matter [in the din] and that political leadership is an established and legislated affair. It is obligatory on the people that they appoint for themselves an imam. This is proven by the Quran, the Sunna, and the consensus of the ummah. As for the Quran, Allah says, ‘O you who believe, obey Allah, obey the Messenger, and those in authority among you.’ [4:59] As for the Sunna, when the Prophet passed away the companions, the muhajirun and the ansar, gathered in the roofed shelter of Bani Sa‘ida al-Khazraji and said: “We heard the Messenger of Allah say, ‘Whoever dies without an imam over him dies a death of jahiliyya.’””25

Numerous other scholars across different schools of thought have also cited this hadith, or variations of it, as evidence for the obligation of establishing the caliphate. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas (d. 1908), the founder of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, quotes this hadith in his book Dururat al-Imam (The Need for the Imam). He writes:

“Let it be clear that an authentic hadith testifies that he who does not recognise the Imam of his time dies the death of ignorance. This hadith is enough to make the heart of a righteous man seek after the Imam of the age, for to die in ignorance is such a great misfortune that no evil or ill luck lies outside its scope. Therefore, in keeping with this testament of Prophet Muhammadsa, it becomes incumbent upon every seeker of truth to persist in his quest for the true Imam.”26

This widespread reliance on the hadith underscores its significance in Islamic legal and theological discourse. The reason for this severe consequence – dying a death of jahiliyya – is that, as will be discussed later, the appointment of a caliph is considered a fard kifaya. If this communal obligation is not fulfilled, the entire community remains and subsequently dies in a state of sin.

Centuries of Islamic scholarship and the Saqifa precedent

Alongside the textual evidence from the Quran and Hadith, which has been mentioned, the urgency with which the companions of Prophet Muhammadsa addressed the issue of leadership upon his demise is a foundational precedent for the obligation of establishing the caliphate.

The incident of the Saqifa, in which the companions prioritised appointing Abu Bakrra as the caliph over the burial of Prophet Muhammadsa, highlights the importance, immediacy and gravity of this obligation.27 This incident has been consistently used as evidence by Muslim scholars across the generations to argue that the establishment of a caliph is among the most critical of communal obligations (fard kifaya) for the Muslim ummah.

Al-Ghazali (d. 1111), who belonged to the Shafi‘i school of jurisprudence and Ash‘ari school of theology, having lived under the Abbasids in a time when the caliphate was a prime discussion, articulated:

“Let it be noted of the first generation, as to how the companions hastened after the death of the Messenger of Allah to appoint the imam (caliph) and contract the pledge of allegiance (bay‘a). Let it be noted how they believed that it was a conclusive obligation (fard), a right and mandated (wajib) with immediacy and urgency. Let it also be noted how they left the preparation of the Messenger of Allah for burial, through being busy with the appointing of the imam.”28

– Views of core classical scholars (600s-1200s)

Prominent scholars across various Islamic schools of thought have consistently reinforced the obligatory nature of the caliphate, reflecting a broad consensus on the importance of leadership in preserving the faith and guiding the Muslim community in accordance with Islamic law. The following is not an exhaustive list but presents key figures to demonstrate this widespread agreement.

The view that establishing the caliphate is a fard kifaya is not exclusive to a specific school of thought within Islam. Ibn Hazm (d. 1064), the Andalusian jurist of the literalist Zahiri school, emphasised that despite the different theological groups that emerged in early Islam, there was unanimity on this issue:

“All the Sunnis (ahl aa-sunna), all the Murji’a, all the Mu’tazila, all the Shi’a, and all the Khawarij have agreed upon the obligatory nature of imamate and that it is mandatory upon the community to submit to a just leader who establishes the laws of God among them and governs according to the rules of the Sacred Law with which the Prophet came.”29

Abu Mansur al-Baghdadi (d. 1037), the Shaf‘i jurist and Ash‘ari theologian, made a similar point, saying that the general body (jumhur) of Sunnis, including theologians (mutakallimun) and jurists (fuqaha’), along with the Shia, the Kharijites, and most of the Mu‘tazila, hold the establishment of caliphate, and pledging allegiance to the caliph, to be an obligation.30

Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal (d. 855), the founder of one of the four major Sunni schools of jurisprudence, is reported to have said that if there is no imam, dissension will inevitably occur. It was also impermissible, according to Imam Ahmad, for anyone to spend a night while considering themselves free of being ruled over by an imam, regardless of whether the imam is morally upright or corrupt.31

Abu al-Hasan al-Ash‘ari (d. 936), who split from the Mu‘tazila movement and founded the eponymous Ash‘ari school of thought, argued that imamate is an ordinance and a necessity known through revelation and that the companions unanimously agreed on this necessity, as explained by al-Baghdadi.32

This view was also echoed by Maturidi scholars such as Abu Shakur as-Salimi (d. 1066) and al-Bazdawi (d. 1100), proving that, regardless of theologically opposing views, there was an agreement across schools of thought on this view.33

Al-Juwayni (d. 1085) highlighted the urgency of the companions to emphasise the need for an imam, caliph or leader over any other matter of the ummah.34

Al-Ghazali (d. 1111), in his Fada’ih al-Batiniyya, relied on the incident to declare the caliphate and imamate a necessity for the preservation of Islam:

“[The companions] knew that even if a moment passed by, without an imam over them, then perhaps a blameworthy incident would afflict them. They would then be embroiled in a great calamity in which opinions were disparate and differed, followed by subjugation to differing opinions.

“[…] Thus, it is conclusive (qati‘) that the appointing of the imam is a necessity for the preservation of Islam.”35

Al-Ghazali could not emphasise the point enough and has also dedicated a whole chapter in his book al-Iqtisad fi l-I‘tiqad to the caliphate and imamate.

Al-Qurtubi, as mentioned earlier, cited the consensus of the companions as decisive proof of the obligation of the caliphate. He considered the appointment of a caliph essential for maintaining the unity and governance of the Muslim community.

Abu Ya‘la ibn al-Farra’ (d. 1066), a prominent Hanbali scholar who has written extensively on this topic in his al-Ahkam al-Sultaniyya, also cites the consensus of the companions as evidence. He adds that had such a discussion and debate not taken place between the companions during the Saqifa incident, it could simply be argued that establishing a caliphate is not an obligation.36

Al-Shahrastani (d. 1153), who was an Ash‘ari follower of the Maliki school, presents the elections of all the rightly guided caliphs as evidence:

“When the death of Abu Bakrra neared, he said [to the companions], ‘Consult amongst yourselves about this matter [of the Caliphate]’. He then described the attributes of ‘Umar [praising him] and chose him as successor. It did not occur to his heart, or that of anyone else, in the least, that it is permissible for there to be no imam. When the death of ‘Umar neared he made the matter one of consultation between six, and they agreed upon ‘Uthman, and after that upon ‘Ali. All of this indicates that the companions, the first and best of the Muslims, agreed that having an imam was necessary. […] This type of unanimous consensus (ijma‘) is a definite evidence (dalil qati‘) for the obligation of the imamate.”37

Al-Baghawi (d. 1122), a renowned Shafi‘i scholar and mufassir of the Quran, explained that when such a period comes upon the Muslims in which there is no appointed leader, it becomes obligatory on those who enact and repeal community decisions (ahl al-hall wa al-aqd) among them to gather and appoint an imam.38

Other classical scholars who emphasised this obligation include al-Mawardi (d. 1058), al-Nasafi (d. 1142), and al-Nawawi (d. 1277).39

– Post-classical and early modern scholars in the Islamic timeline (1300s-1700)

Ibn Taymiyya (d. 1328), the prominent Hanbali scholar and theologian, writes in his al-Siyasah al-Shar‘iyyah:

“It is imperative to know that the office in charge of governing the people is one of the greatest obligations of the deen. Nay, there is no establishment of the deen or the dunya except by it.”40

Al-Taftazani (d. 1390), the Hanafi scholar and Ash‘ari theologian, declared the imamate “the most important of obligations” upon the Muslim community.41

Mansur al-Buhuti (d. 1641), a Hanbali Egyptian scholar and jurist, explicitly labelled the establishment of a greater imam – i.e. a caliph – a fard kifaya in his book Kashshaf al-Qina.42

Other prominent scholars who affirmed the caliphate as a communal obligation during this period include Ibn Taymiyya (d. 1328), al-Iji (d. 1355), Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406), Ibn Hajar al-Haytami (d. 1567), ar-Ramli (d. 1596), and al-Haskafi (d. 1677).43

– Modern voices (1700s onwards)

Shah Waliullah al-Dehlwi (d. 1762) writes in his book al-Hujjat al-Baligha:

“Know that it is obligatory for there to be in the jama’a of the Muslims a khalifah for interests that simply cannot be fulfilled except with his presence…”44

Al-Shawkani (d.1834) understood the importance of the Saqifa incident regarding appointing an imam, and that too with urgency.45

Rashid Rida (d. 1935), the 19th-century reformist and intellectual, highlighted the unanimous position of the early generations in considering the establishment of the caliphate to be a fard kifaya:

“The pious ancestors (salaf) of the ummah were in consensus, and the Sunnis, as well as the masses of the other sects that the position of the imam – that is, the appointing him as trustee over the ummah, is obligatory for Muslims according to the shari‘a […] the position of the caliph is a fard kifaya (an obligation contingent upon sufficiency) and that those who are obliged to fill it are the ahl al-hall wa al-aqd in the ummah.”46

Egyptian scholar Abdul Rahman al-Juzayri (d. 1941) states that the four Imams unanimously agreed that appointing a caliph is obligatory, and that Muslims cannot have two Imams simultaneously.47

Muhammad ibn Ibrahim al-Tuwaijri, who is a contemporary Salafi scholar from Burayda, described the caliphate as a communal obligation with specific roles assigned to two specific groups:

“The caliphate is a communal obligation and addresses two groups of people: The consultative body (ahl al-shura) whose responsibility is to choose the caliph, and those qualified for leadership (ahl al-imama), who must be prepared to assume the role of caliph if selected.”48

Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas has emphasised on many occasions the importance and obligation of establishing a caliphate. In his book Dururat al-Imam (The Need for the Imam), he cites the hadith about recognising the Imam of the age, and the severe consequences of not doing so, as mentioned earlier. In Al-Wasiyyat (The Will), he discusses his view on two Divine manifestations: the first being prophethood and the second being the caliphate that succeeds a prophet. He was also of the view that the caliphate “on the precepts of prophethood” would continue after the coming of the Imam Mahdi.

Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra, the second successor of Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas, also writes regarding the urgency of establishing a caliphate, which is in line with the practical example of the companions of Prophet Muhammadsa:

“The issue of khilafa is indeed a very important one and should be resolved as early as possible.”49

However, this opinion has not gone unopposed throughout Islamic intellectual discourse. There have been scholars such as Hatim al-Asamm (as mentioned earlier), some from the Kharijites, and others from the Qadarites, who have mildly, and sometimes strongly, opposed the urgency and even sometimes the very obligation of establishing a caliphate.

While dissenting voices exist, the overwhelming weight of scholarly opinion across centuries and schools of thought supports the view that establishing the caliphate is a fard kifaya. The practical example of the companions during the Saqifa incident further underscores the urgency and importance of this obligation.

Due to brevity, references from the following scholars, who also hold the view that caliphate is an obligation, have not been added to the article and can be consulted as further reading: Hanafi scholars including Abu Shakur al-Salimi, al-Bazdawi, al-Kasani, al-Andakani, al-Qutlubagha; Shafi‘i scholars Abu al-Abbas ibn al-Rifaa and Jalal al-Din al-Mahalli; and Maliki scholar Ibn Abdillah al-Tamimi al-Siqilli (d. 1061).

Understanding fard kifaya and its implications

In Islam, actions which are compulsory to be carried out are called obligations. These are classified into two types: individual obligations (fard ayn), which pertain solely to the individual, such as obligatory prayers and fasting, and communal obligations (fard kifaya), which Muslims are required to fulfil collectively.

A fard kifaya is a duty that, if fulfilled by some members of the Muslim community, absolves the rest from individual responsibility. This is why it is also known as an obligation of sufficiency, as a sufficient number of people are needed to complete it, and they are sufficient for this purpose. However, if no one fulfils it, the entire community is considered sinful. Examples include the funeral prayer, Eid prayers, and the issue at hand: the establishment of the caliphate.

Hanbali scholar Ibn al-Lahham (d. 1400), in his book al-Qawaid wa al-Fawaid al-Usuliyyah, defines each type of obligation and explains the difference between the two:

“If an obligatory act is required to be performed by every individual specifically or by a designated individual (as in the unique obligations of the Prophet), it is classified as fard ayn (individual obligation). However, if the purpose of the obligation is simply the performance of the act itself, regardless of who performs it, it is called fard kifaya (communal obligation).

“It is referred to as such (kifaya or sufficiency) because the performance by some suffices to remove the burden of sin from the rest.”50

Al-Zarkashi (d. 1392) described the purpose behind each: Fard ayn is intended to test the individuals obligated with it, as it requires each person to fulfil the duty personally. In contrast, the purpose of fard kifaya is to ensure that the action itself is carried out, regardless of who performs it.51

To further elaborate on the distinction between the two, Ibn al-Lahham cites a statement by Sunni scholar Shihab al-Din al-Qarafi (d. 1285). He explains that the benefit of a fard ayn is repeated with its repetition, such as the five daily prayers. Their benefit lies in submission to Allah, glorifying him, engaging in private conversations with him, humbling oneself before Him, and standing in His presence. These manners increase as the prayers are repeated.52 This increase in reward is not only limited to mandatory actions, but also applies to recommended acts such as the witr prayer, fasting on virtuous days, performing tawaf, and giving voluntary charity.

Fard kifaya, on the other hand, al Qarafi explains, refers to obligations whose benefit does not increase with repetition, such as the rescuing of a drowning person. Once one individual fulfils the obligation, a second rescuer entering the water does not provide any additional benefit. Therefore, it is classed as a fard kifaya in Islamic law to avoid redundancy in the action.

Because the establishment of the caliphate is a fard kifaya, if it is not carried out and the responsibility for it is not taken by anyone, all members of the Muslim community bear the burden of the sin collectively. This was also explained earlier by Shafi‘i jurist al-Mawardi (d. 1058), and Hanbali jurist Abu Ya’la ibn al-Farra‘ (d. 1066).53

Ibn al Lahham writes that it is sufficient for the obligation of fard kifaya to be lifted if there is a strong presumption (ghalabat al-zann) that another group has fulfilled it. This view has been expressed by Abu Ya’la ibn al-Farra‘, Ibn Taymiyya, and others.54

The role of ahl al-hall wa al-aqd in establishing the caliphate

The ahl al-hall wa al-aqd play an integral role in establishing the caliphate. This term, in a technical sense regarding the appointment of caliphs and imams, was not used during Prophet Muhammad’ssa lifetime. During the time of the four rightly guided caliphs, it started to be used but in a general sense, referring to deputies and rulers of different regions that had been appointed by the caliphs. It was later that this term began to be used in a technical sense.

One of the earliest uses of this term in a technical sense was by Abul Hasan al-Ash‘ari, who described the companions who recognised the caliphate of Hazrat Alira as the “ahl al-hall wa al-aqd of the companions.”55

Alongside al-Mawardi and Abu Ya’la ibn al-Farra, there are many scholars who have mentioned the necessity of this group. The modern-day Egyptian intellectual and reformist Rashid Rida has written that the establishment of the caliphate is a fard kifaya, and that “those who are obliged to fulfil it are the ahl al-hall wa al-aqd of the ummah.”56

But who exactly are they, and what kind of people is this electoral body made up of? The following definition of the group can be found in the Kuwaiti Encyclopaedia of Islamic Jurisprudence:

“The term ahl al-hall wa al-aqd refers to the influential individuals among the scholars, leaders, and notable figures of society who ensure the objectives of governance are achieved, namely, the ability and authority to manage affairs effectively. The phrase is derived from resolving (hall) and binding (aqd) matters.”57

In a similar manner, the contemporary Hanbali scholar Muhammad ibn Ibrahim al-Tuwaijri, in his Encyclopaedia of Islamic Jurisprudence, writes:

“The selection and pledge of allegiance to the caliph are carried out by the ahl al-hall wa al-aqd – the people of authority, including righteous scholars, leaders, and prominent figures. They act on behalf of the nation in choosing the caliph, in the way that the Muhajirun and Ansar selected the rightly guided caliphs.”58

The responsibility of electing the caliph is a heavy one. For this reason, there are certain qualities which should be present in the people who make up this electoral body. These have been collected in the Kuwaiti Encyclopaedia from various sources, such as al-Ahkam al-Sultaniyyah by al-Mawardi:

- Justice: This includes all the conditions required for justice and uprightness in bearing witness, such as being Muslim, sane, mature, free from sin (fisq), and possessing complete moral integrity.

- Knowledge: They must have sufficient knowledge to discern who is eligible for the position of imamate based on the required conditions for leadership.

- Sound judgment and wisdom: These are essential for selecting the most qualified and suitable individual for the imamate.

- They must be individuals of authority and influence (shawka) whose opinions are followed by the people and whose decisions are heeded so that the objectives of governance can be effectively achieved.

- Sincerity and a genuine desire for the well-being of the Muslims.

There is an opinion held amongst scholars, such as al-Mawardi, who writes in his al-Ahkam al-Sultaniyya that there is a group from within the ahl al-hall wa al-aqd who will be entrusted with the task of choosing the caliph, and that is the ahl al-ikhtiar. It is possible that the ahl al-ikhtiar consists of all of the members of ahl al-hall wa al-aqd, or only a select number from them.59

The appointment of the ahl al-ikhtiar is carried out in one of two ways. Either the caliph appoints them directly, such as when Umarra designated six members from the ahl al-hall wa al-aqd to choose one among them as the next caliph for the Muslim after him. Or, if the caliph does not designate a specific group of ahl al-ikhtiar, then those who are able to attend from the ahl al-hall wa al-aqd suffice to conduct the election – meaning, whoever is present and able to attend. In this case, their presence is equivalent to a formal appointment.60

There has been a difference of opinion among Muslim scholars as to the number of ahl al-hall wa al-aqd that are required and necessary to establish the caliphate. This is the number of people needed in agreement in order for the caliphate to be valid.

One opinion is that the caliphate is not valid until the majority of ahl al-hall wa al-aqd from every region agree, ensuring widespread acceptance and collective submission to the leader. This view is upheld by the Hanbali school. Ahmad bin Hanbal stated, “The legitimate leader is the one whom everyone agrees upon, saying, ‘This is our leader.’”61

Another view is that at least five members must agree to establish leadership. Either all five must collectively appoint the leader, or one of them does so with the approval of the other four.

Additionally, a third opinion suggests that no specific number is required. This is according to the Hanafi and Shafi‘i schools, who believe that leadership can be established by the appointment of a group of ahl al-hall wa al-aqd without specifying the exact number.62

The tasks that are meant to be carried out by the ahl al-hall wa al-aqd include not only appointing the caliph, about which there is an ijma among the Sunni scholars with no disagreement as stated by al-Mawardi, but also, if the elected leader is absent when the current leader dies, the ahl al-hall wa al-aqd are responsible for summoning him. During his absence, they can also appoint a deputy to serve temporarily on behalf of the caliph until he arrives. They pledge allegiance, according to al-Mawardi, to this deputy as a representative, not as a full caliph.63

It is important to note that the concept of deposing a caliph is highly contested, and there is no consensus among scholars on this issue. While some hold the view that the ahl al-hall wa al-aqd have the authority to remove a caliph for valid reasons, such as a clear violation of Islamic law, others strongly oppose this, arguing that it leads to instability and fitna (strife).

This would practically mean that the ahl al-hall wa al-aqd are the people in absolute control and not the caliph, for they possess the power to depose him. Going against the sharia can be subjective, as is quite evident in the state of the ummah today, and if he goes against their variant of the sharia, then they can remove him.

Then, a review of historical events reveals a further distinction between ahl al-shura and ahl al-hall wa al-aqd. The defining characteristic of ahl al-shura is “knowledge,” whereas the defining characteristic of ahl al-hall wa al-aqd is “authority” (shawka, or strength).

It has been narrated that Abu Bakrra would consult individuals like Umar ibn al-Khattabra, Uthman ibn Affanra, Abdur-Rahman ibn Awf, Mu’adh ibn Jabal, Ubayy ibn Ka‘b, and Zayd ibn Thabit when faced with significant matters. All these companions were known for issuing religious verdicts during the caliphate of Abu Bakrra, and he sought their counsel, making them from among the ahl al-shura.

On the other hand, among those who participated in pledging allegiance to Abu Bakrra at Saqifa from ahl al-hall wa al-aqd was Bashir ibn Sa‘d. However, Bashir was not known as one of the scholars issuing religious verdicts among the companions. Instead, he was influential and respected in his tribe, the Khazraj. It is said that he was the first from the Ansar to pledge allegiance to Abu Bakrra on the day of Saqifa.64

Due to the seeming impossibility of electing even the ahl al-hall wa al-aqd, electing a caliph of all the Muslims in the world turns into a mere romantic fantasy. Establishing the caliphate, thus, becomes a humanly impossible task, where divine intervention will have to come into effect, taking us back to the promise of Allah in Surah an-Nur.

Conclusion: The apparent impossibility in the present day

We have seen that establishing the caliphate is a fard kifaya – a ruling derived from the Holy Quran, Hadith, and the practical example of the companions of Prophet Muhammadsa. Based on these sources, Islamic scholars throughout the ages have agreed that it is imperative to establish a caliphate. Allegiance must also be pledged to the caliph as per the hadith of Prophet Muhammadsa.

This obligation, as a fard kifaya, carries serious implications: if unfulfilled by a sufficient group from within the ummah – in this case, the ahl al-hall wa al-aqd (those qualified to elect a leader) – the entire ummah bears the weight of collective sin. Further still, neglecting this obligation could result in dying a “death of jahiliyya” as per the hadith of Prophet Muhammadsa, which everyone can agree is a spiritually dangerous state.

Yet, in today’s fractured Muslim world, the practical establishment of a unified caliphate acceptable to all Muslims appears nearly impossible. The idea of forming a credible ahl al-hall wa al-aqd accepted by all, let alone agreeing on a single leader with universal legitimacy, is beyond current political and sectarian realities.

It is precisely this impasse that suggests that the election of such a caliph is not possible without divine intervention, as mentioned in Surah an-Nur. In the promise found in verse 56, Allah takes it upon Himself to implement this task. This does not detract from the need for the ahl al-hall wa al-aqd. They are simply the means of Allah’s action. This is the only way Muslims will begin to unite under one leadership. Allah does not merely make the promise of caliphate and stop there, but rather, by way of Arabic grammar, stresses and emphasises this fact a great deal. Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra writes:

“In this verse [an-Nur: 56], Allah the Almighty’s promise is mentioned with the words wa’ada Allah [Allah promises], and then this promise of giving khilafat is emphasised with the imperative lam (lam takeed) and imperative nun (nun takeed). This tells us that Allah Himself will do this, and will most definitely do so. Then the verse goes on to say that Allah will definitely, most definitely, grant those khulafa a prestige. And then says that Allah will definitely, most definitely, convert fear into peace. Hence, by using the imperative lam and imperative nun thrice, the point has been emphasised greatly that it is Allah Himself that will make this happen, and nobody or nothing will interfere.”65

In this context, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community presents a modern example: a functioning caliphate which was established in 1908. There is no doubt that a theological debate and varied responses exist across the Muslim world regarding this caliphate, but mere scrutiny does not necessitate falsehood – every caliphate in the past has been scrutinised heavily, including the rightly guided one. The very definition of what a caliph should be, and how a caliphate should look and function, has never been agreed upon. There are differences of opinion in almost every matter related to this, so simply rejecting a claimant of caliphate due to scrutiny is not only unfair and unreasonable, but also lacks academic integrity.

We know there will definitely be a caliphate based “on the precepts of prophethood”. Some scholars believe this will occur after the appearance of Imam Mahdi, as mentioned earlier. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas claimed to be the Imam Mahdi and Promised Reformer of the latter days, and after him, caliphate continued in the same way as it followed after Prophet Muhammadsa. The parallel is there. Whether his claim was legitimate or not is a valid question, but one which requires a thorough and unbiased investigation.

Given the gravity of the obligation and the potential consequences of its neglect, a passive stance is not an option. The bottom line is that until Muslims unite under one caliph and pledge allegiance to him, the state of the ummah will not improve.

Without recognising the Imam of the age and pledging sincere allegiance to a caliphate, every Muslim carries the risk of dying the death of jahiliyya and consequently in a state of sin. No Muslim in his right mind would want this, so this is not a matter to sit back and not worry about. It is extremely important, and it’s about time Muslims took this seriously.

Therefore, on the one hand, the obligation of the caliphate remains, while on the other, the ummah continues to grapple with intense division. The consequences of this neglected duty are immense and too grave to ignore. It is upon every Muslim individually to do their research and not reject something based on mere hearsay and prejudice.

Endnotes:

1. Musnad Ahmad, Vol. 5, Hadith 23885

2. Ibid.

3. Al-Albani, Silsila al-Hadith al-Sahiha

4. Amin Muhammad Jamal ad-Din, Al-Qol al-Mubeen fi al-Ashrat al-Sughra li Yaum al-Din, pp. 128-131

5. “Shaykh Muhammad Al-Yaqoubi: Refuting ISIS (FULL)”, www.youtube.com, 24 February 2016

6. Al-Qurtubi, al-Jami‘ li al-Ahkam al-Quran, Vol. 1, pp. 264-265; Ibn Taymiyya, al-Siyasah al-Shar‘iyyah, p.129; Al-Ghazali, al-Iqtisad fi al-Itiqad, p. 199

7. Sahih Muslim, The Book on Government, Hadith 1851a; Musnad Ahmad, Vol. 4, Hadith 16876

8. Surah al-Baqarah, Ch.2: V.31; Surah Sad, Ch.38: V.27

9. Surah al-Baqarah, Ch.2: V.152

10. Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad, Barakat-e-Khilafat (Blessings of Khilafat)

11. Ibid.

12. Al-Taftazani, Sharh al-Aqaid al-Nasafiyyah, p. 242

13. Al-Nawawi, al-Rawdat al-Talibin, 10:49

14. The Kuwaiti Encyclopaedia of Islamic Jurisprudence, Under entry of ‘imamate’

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. Surah al-Baqarah, Ch.2: V.31

18. Al-Qurtubi, al-Jami‘ li al-Ahkam al-Quran, Vol. 1, pp. 148-149

19. Al-Juwayni, Ghiyath al-Umam fi-Iltiyath al-Zulam, pp. 22–23

20. Sahih Muslim, The Book on Government, Hadith 1851a; Musnad Ahmad, Vol. 4, Hadith 16876

21. Al-Shawkani, al-Sayl al-Jarrar al-Mutadaffiq ala Hada’iq al-Azhar, Vol. 1, p. 936

22. Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani, Fath al-Bari Sharh Sahih al-Bukhari, Commentary of Hadith 6530, 13/7

23. Al-Taftazani, Sharh al-Aqaid al-Nasafiyyah

24. Al-Taftazani, Sharh al-Aqaid al-Nasafiyyah, p.353-354

25. Al-Salimi, Al-Tamhid fi Bayan al-Tawhid, p. 309

26. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Dururat al-Imam (The Need for the Imam), p. 1

27. Al-Tabari, Tarikh, Vol. 2, p. 452

28. Al-Ghazali, Fada‘ih al-Batiniyya wa-Fada‘il al-Mustazhiriyya, p.171

29. Ibn Hazm, al-Fisal fi al-Milal wa al-Ahwaʿ wa al-Nihal, 4:148

30. Al-Baghdadi, Usul al-Din and al-Farq bayn al-Firaq

31. “Impermissible to spend a night”: Al-Barbahari, Sharḥ al-Sunnah, p. 77; “Dissension is inevitable”: Abu Bakr al-Khallal, al-Sunnah, p. 32 (#11)

32. Cf. Lambton, Ann K. S., State and Government in Medieval Islam: An Introduction to the Study of Islamic Political Theory – The Jurists, pp. 77-78

33. Al-Salimi: mentioned earlier; Al-Bazdawi, Usul al-Din, p. 191

34. Ibn al-Rif‘ah, Kifayat al-Nabih, 18:4

35. Al-Ghazali, Fada‘ih al-Batiniyya wa-Fada‘il al-Mustazhiriyya, p.171

36. Abu Ya‘la ibn al-Farra‘, al-Ahkam al-Sultaniyya, p. 19

37. Al-Shahrastani, Nihayat al-Iqdam fi Ilm al-Kalam, Vol. 1, p. 268

38. Al-Baghawi, al-Tahdhib fi Fiqh al-Imam al-Shafi‘i, 7:264.

39. Al-Mawardi, al-Ahkam al-Sultaniyya; al-Nasafi, al-Aqa’id al-Nasafiyyah, p.354; al-Nawawi, Sharh Sahih Muslim, 12:205 & 7:36

40. Ibn Taymiyyah, al-Siyasah al-Shar’iyyah, p.129

41. Al-Taftazani, Sharh al- Aqa’id al-Nasafiyyah, p.353-354

42. Al-Buhuti, Kashshaf al-Qinaa’ an Matn al-Iqnaa’, 6:158

43. Al-Iji, al-Mawaqif fi Ilm al-Kalam, 3:579-580; Ibn Khaldun, al-Muqaddimah, Chapter 3, Section 26; Ibn Hajar al-Haytami, al-Sawaa’iq al-Muhriqah, 1:25; al-Ramli, Ghayat al-Bayan fi Sharah Zabd ibn Raslan, 1:15; al-Haskafi and Ibn Abidin, Radd al-Muh ala al-Durr al-Mukhtar, 1: 548 (Ibn Abidin’s hashiya [annotation] on Haskafi’s work)

44. Shah Waliullah al-Dehlawi, Hujjat Allahi al-Baligha, 2:229

45. Al-Shawkani, al-Sayl al-Jarrar al-Mutadaffiq ‘ala Hada’iq al-Azhar, 1:936

46. Rashid Rida, al-Khilafa aw al-Imamah al-Uzma, (From the Nation State to the State of the Khilafah: Renewal of ‘Islamic Legal Politics'”. The State in Contemporary Islamic Thought, pp. 73, 81.)

47. al-Juzayri, al-Fiqh ala al-Mathahib al-Arba’a, 5:416

48. Muhammad ibn Ibrahim al-Tuwaijri, Encyclopedia of Islamic Jurisprudence, Vol. 5, p. 286.

49. Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad, Barakat-e-Khilafat (Blessings of Khilafat), p. 21

50. Ibn al-Lahham, Al-Qawa‘id wa al-Fawa’id al-Usuliyyah, Qa’idah 49, p. 253

51. Al-Zarkashi, Al Bahr al-Muhit, 1:242

52. Al-Qarafi, Al-Furuq, Vol. 1, p. 166; Ibn al-Lahham, Al-Qawaid wa al-Fawa’id al-Usuliyyah, Qa’idah 49

53. Abu Ya‘la ibn al-Farra‘, al-Ahkam al-Sultaniyya, pp. 19-20; Al-Mawardi, al-Ahkam al-Sultaniyya, pp. 5-6

54. Ibn al-Lahham, Al-Qawa‘id wa al-Fawa’id al-Usuliyyah, Qa’idah 49

55. Abu al-Hasan al-Ash‘ari, al-Ibanah an Usul al-Diyana, p. 258 (Taken from Ummatics.org)

56. Rashid Rida, al-Khilafa aw al-Imamah al-Uzma, (From the Nation State to the State of the Khilafah: Renewal of ‘Islamic Legal Politics'”. The State in Contemporary Islamic Thought, pp. 73, 81.)

57. The Kuwaiti Encyclopaedia of Islamic Jurisprudence, Under “ahl al-hall wa al-aqd”

58. Muhammad ibn Ibrahim al-Tuwaijri, Encyclopaedia of Islamic Jurisprudence

59. Al-Mawardi, al-Ahkam al-Sultaniyya

60. The Kuwaiti Encyclopaedia of Islamic Jurisprudence

61. Abu Ya‘la ibn al-Farra‘, al-Ahkam al-Sultaniyya

62. Abu Mansur Abdul Qahir al-Baghdadi, Usul al-Din; Abu Ya‘la ibn al-Farra‘, al-Ahkam al-Sultaniyya; Al-Mawardi, al-Ahkam al-Sultaniyya

63. Al-Mawardi, al-Ahkam al-Sultaniyya

64. Ibn Athir, Usd al-Ghabah fi Ma‘rifat al-Sahaba

65. Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad , Mansab-e-Khilafat, p. 60