Tahmeed Ahmad, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre

History will rejoice the victor, while opponents gradually fade away. Great names endure, while those who once stood against them are pushed to the margins, remembered only in passing. This would be the fate of Abdullah Athim. Once a central figure in the famous religious debates of 1893, Jang-e-Muqaddas (The Holy War), his name has all but vanished, remembered today only in the footnotes.1

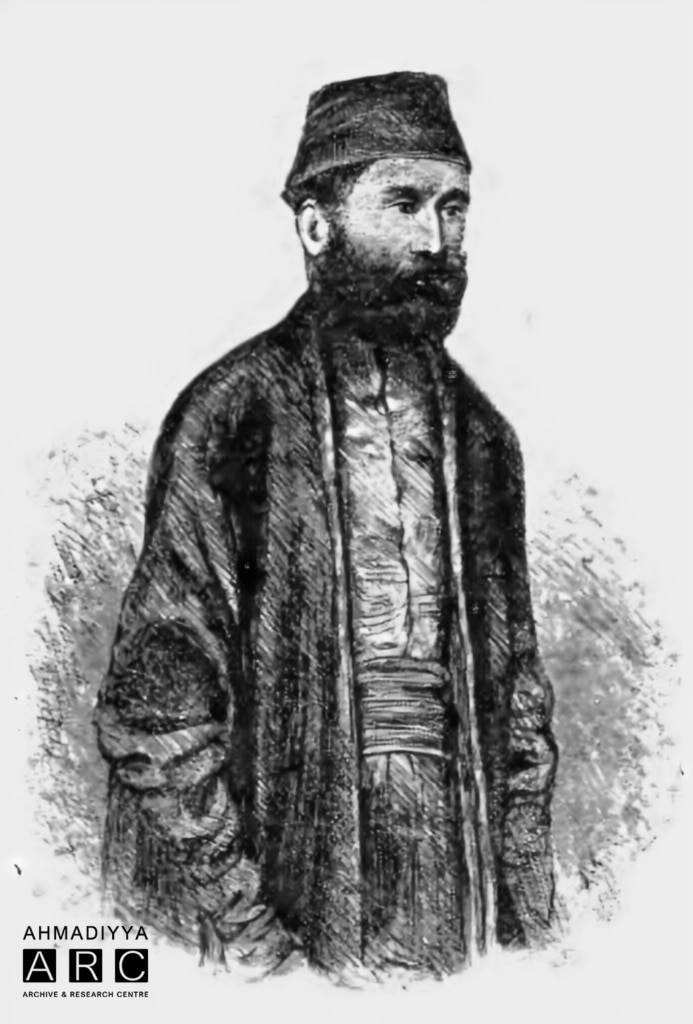

Abdullah Athim, also known as Atham in Ahmadiyya literature, was once a prominent figure in Christianity during the British Raj. He is recognised as one of the most notable native Muslim converts of the 19th century.2 Today, the only reason you and I might recognise Athim’s name is because of Anjam-e-Atham, a book written by Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas of Qadian.3 The name Athim no longer represents him, but is evidence supporting the truthfulness of Islam.

One may wonder why this chapter is even worth opening. Was it not enough that Athim was defeated on the battlefield of theological discourse? The answer lies in the context. As we move further away from the advent of the Promised Messiahas, much of the historical background risks being lost, and with it, the true weight of certain events – especially incidents from the earlier years of the Jamaat’s mission, when records were scarce and resources were limited.

The very first newspaper of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat, Al Hakam, was not established until 1897,4 four years after Jang-e-Muqaddas. In those early days, the Jamaat had few resources, yet Hazrat Ahmadas stood undaunted before towering figures of his time. Failure to gauge the stature of those he faced means we cannot truly grasp the magnitude of their fall. After all, David’s triumph can only be appreciated when we know the measure of Goliath.

So, let me present a short sketch of who Abdullah Athim really was: a sword of Christianity shattered against the shield of Islam.

Early life of Abdullah

Before his conversion to Christianity, Abdullah Athim was known as Sayyid Abdullah,5 later Munshi Abdullah.6 He was born in 1828 to a Muslim family in Ambala, India. His family was likely fairly wealthy, considering his education in Urdu and Persian, among other languages.7 However, at first, he did not know any English, and when the opportunity arose, he left with the Medhu Sudun Seal for Karachi.8 MS Seal was a catechist based in Karachi, who was touring Sindh at the time.9

Once Abdullah had learned the English language, he quickly advanced to the position of tahsildar, a high role in the civil service.10 He left this position in 1849 and entered the “Free-school” under MS Seal. There, he first encountered Christian literature written against Islam.11 Convinced of his own ability, especially in a country where literacy stood at barely 3.1% in 1872,12 Abdullah decided to write a response to these attacks.

Abdullah began writing a pamphlet to refute these allegations. But as he studied works like Mizan al-Haqq, his arguments quickly collapsed. Both Mr Seal and Rev Abraham Matchett record that Abdullah grew frustrated, abandoned his work, and eventually tore up the draft he had written.13,14

I do not believe Abdullah was ever a practising Muslim, as he admits the state of his heart in a letter to Rev KG Pfander:

“I first turned a rationalist, then I became an unbelieving philosopher, and, ultimately, a materialist and pantheist.”15

Conversion to Christianity

Just as Abdullah asserts that he was unable to defend Islam, a second tragedy struck. In 1851, his wife departed this world due to an illness, and Abdullah had to take her remains to his hometown, Ambala. These recent events led to some serious doubts about his faith. In an attempt to resolve the doubts, he reached out to scholars far and wide with his questions, but this call went unanswered. This marked the beginning of his journey towards Christianity.16

The account of his conversion was widely circulated, with numerous versions published. Since there is no need to delve into the specifics at this time, I will simply note that Munshi Sayyid Abdullah was baptised on 28 March 1853, alongside his two sons by Rev Abraham Matchett of Karachi. He subsequently took on the name Abdullah Athim.17

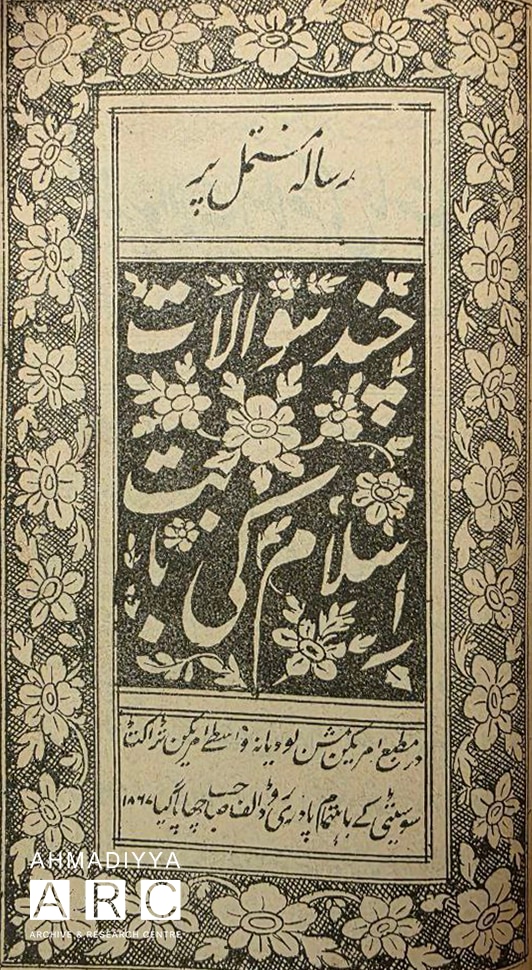

Earlier, I mentioned Athim distributing some questions to Islamic scholars. These became the basis of Athim’s initial rise to fame. Titled Chand Su‘alat Islam ki Babat was dubbed Abdullah’s 23 Questions or Kurachee [Karachi] Questions.

Missionaries like the Rev W Clark of Amritsar would relate events of Muslims running away from the mere mention of Athim or his questions:18

“On Friday last, as I was coming in from the city, I met in the dark, at my door, a native, well dressed, who had a letter for us. It proved to be from Mr. Matchett, our Missionary at Karachi, introducing a Christian gentleman, by name Abdullah. He had been a native judge at Karachi, and had just been baptized by Mr. Matchett. He has been an inquirer for eight years, and lately published several questions about Mahommedanism, and sent them to all the principal molwis of Delhi, Agra, &c. No man has ever been able to answer them.”19

His fame reached another level when, in 1852, Sir William Muir20 included the Questions as an appendix in Bahs-i-Mufidul-Am fi Tahqiq-ul-Islam, a controversy between a Hindu (Ramchandra) and the Qazi of Delhi. The appendix gained more popularity than the debate and became the reason for countless conversions across India.21

Changing his name to Abdullah Athim

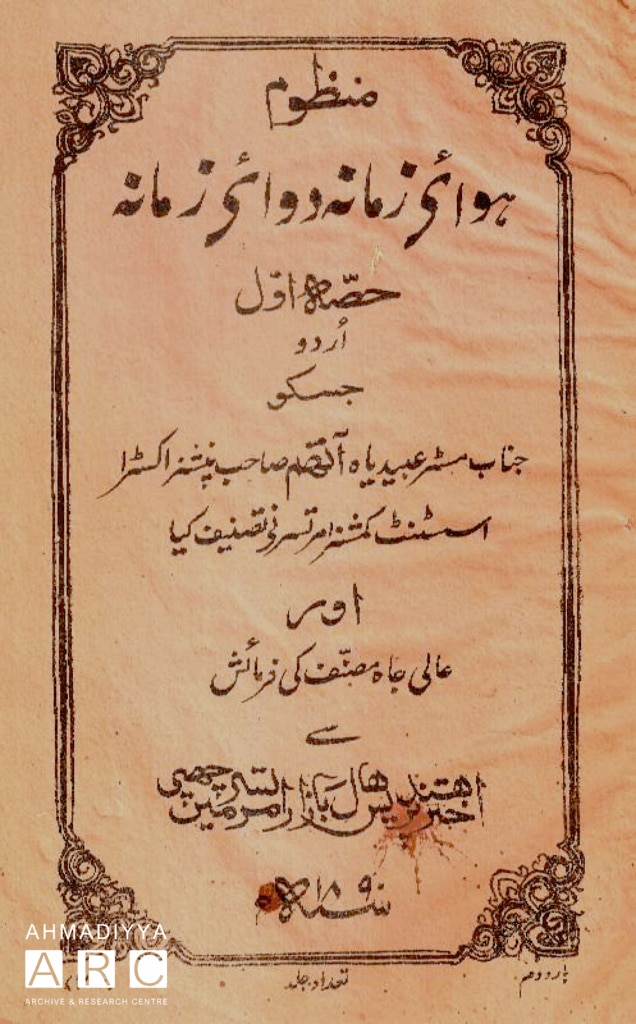

As per tradition, Abdullah wanted to adopt a Christian name to signify his “rebirth” and new faith. He chose the name Athim, which means “sinner.” In fact, the first signature he wrote as a Christian simply stated “Abdullah Ism,”22 meaning “sin.” He replaced his old name, Abdullah, and transformed it into “Ubaid-Yah,” with ‘Ubaid’ derived from “abd” and “Yahweh” substituting for “Allah.”23

Official documents, such as those from the CMS and his gravestone, however, use the spelling Abdullah Athim. He personally preferred to sign his name as “Ubaid-Yah.”24 In recent years, the spelling and usage of his name has changed to Abdullah Atham.

Working for the Church Mission Society

Athim began working for the Church Mission Society in 1853, starting with volunteer work for the mission in Karachi. One of his earliest experiences was joining Rev Abraham Matchett on a tour through Sindh:

“The Rev. A. Matchett, in the early part of the year, made tour in Sindh, accompanied by convert from Mahommedanism called Abdullah. They went to the north as far as Khanghar, preaching Christ to the natives.”25

He also translated St Matthew’s Gospel into Sindhi,26 and in 1855, he was married to the eldest daughter of Rev William Basten of the American Presbyterian Mission.27 Thus, Athim embarked on a remarkable career, engaging in debates, giving lectures, and writing many books.

“So began the Missions in the Punjab. The province of Sindh through which the Punjab rivers, united in the Indus, find their way to the sea, had already been entered. Converts were quickly granted; few in number, but men of mark, Mohammedans, Brahmans, and Sikhs, such as Abdullah Athim, the Moslem disputant, at Karachi”28

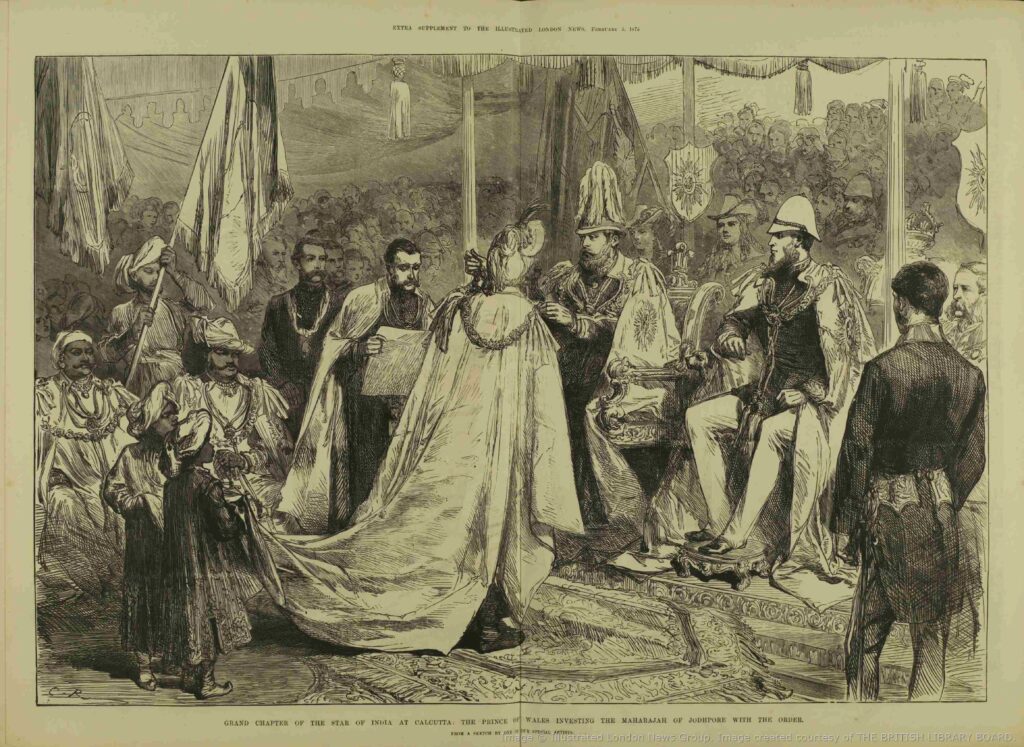

The Prince of Wales in 1876

In January 1876, during his tour of India, the Prince of Wales visited Amritsar and was received at the City Mission House by Rev R Clark. Abdullah Athim, then an Extra Assistant Commissioner, presented an address and copies of the Bible in several languages on behalf of the Native Christians, alongside two other individuals.29

The Prince’s acceptance of these gifts, later acknowledged in a letter of thanks, was widely reported in the press.30 The event made it clear that Abdullah Athim was their representative to the CMS.

Government Position: Tahsildar to Extra Assistant Commissioner

Abdullah Athim’s government career was closely tied to his Christian conversion and the support of Rev Robert Clark. After Athim resigned his earlier high rank for work in the CMS, Clark personally advocated on his behalf to senior officials in Lahore. He explained Athim’s sacrifice and persuaded the Lieutenant-Governor and Financial Commissioner to appoint him to the government service as a Tahsildar.31

Athim went on to serve in Ajnala, Tarn Taran, and Batala with distinction, earning promotion as Extra Assistant Commissioner. By 1873, he was recorded in this role at Sialkot,32 later serving in Ambala and Karnal33 with a strong reputation for honesty and competence. Advanced to 2nd Class, 2nd Grade in 1882,34 he retired on pension in 1884.35

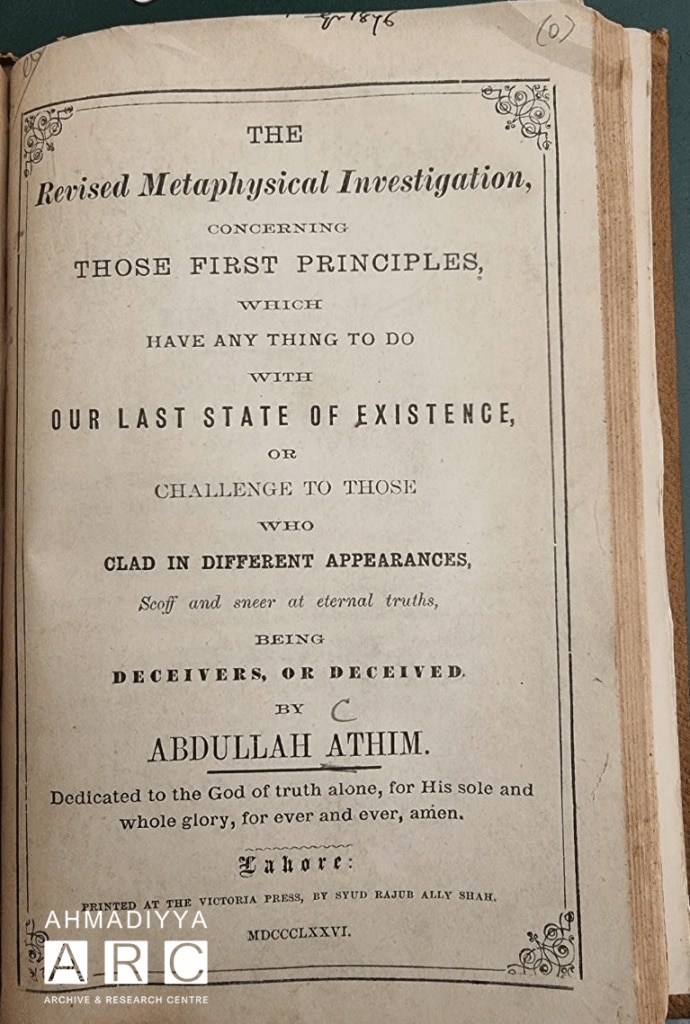

Literary contributions

In addition to his position in the CMS and his public service, Athim was a highly prolific author. Nevertheless, since this article – as it currently stands – cannot thoroughly delve into his works, I shall list the writings I managed to locate here, reserving the discussion of their content for a later date.

Chand Sualat (Reprint 1867)

Asligt i Qur’an (1873)

Kalid i Taurit (1873)

Hikmat i Usal i Hamah-ost (1873)

Dahakti bhatti ka bayan (1876)

Krishna ka ahwal (1876)

Ek Badshah Ki Hikayat (1876)

The Revised Metaphysical Investigation (1876)

Kari mashiyat (1887)

Zuf i umur i ahamm (1893)

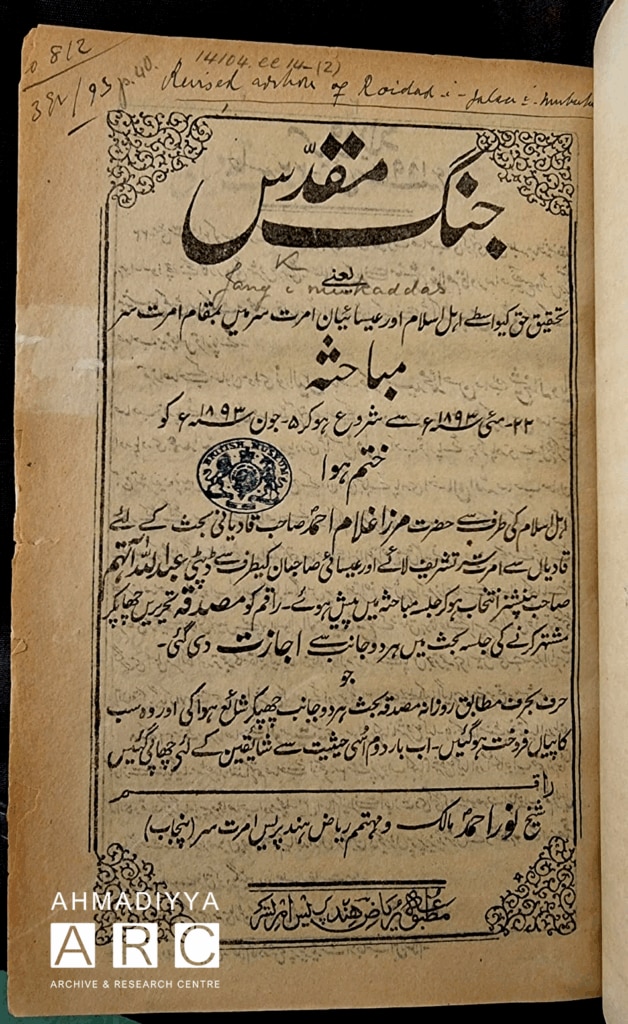

Jang i Mukaddas (1893)

These are just the books I have been able to locate to date. If I were to list all the books affiliated with him, the list would need to be expanded threefold. We have also not yet included speeches, lectures, and translation works.

The Native Church

After retiring, Athim dedicated all of his time to the CMS. Given his prior role as a catechist in Karachi in 1860,36 it came as no surprise that he became an honorary priest in April 1884.37 He was now more engaged than ever and joined the likes of Rev Robert Clark, Dr Henry M Clark, and Rev Imad-ud-Din at Amritsar:

“About that time a valiant-hearted man, Abdulla Athim, declared for Christ in Amballa. He is now enjoying his pension after years of honourable service as Extra Assistant Commissioner. He is now with us in Amritsar.”38

By this point in the article, for those even briefly acquainted with Athim’s life, the dots should begin to align. Abdullah Athim was getting to the pinnacle of his life. In 1888, when his benefactor, Rev A Matchett, passed, one-third of his obituary was spent on Athim’s achievements.39

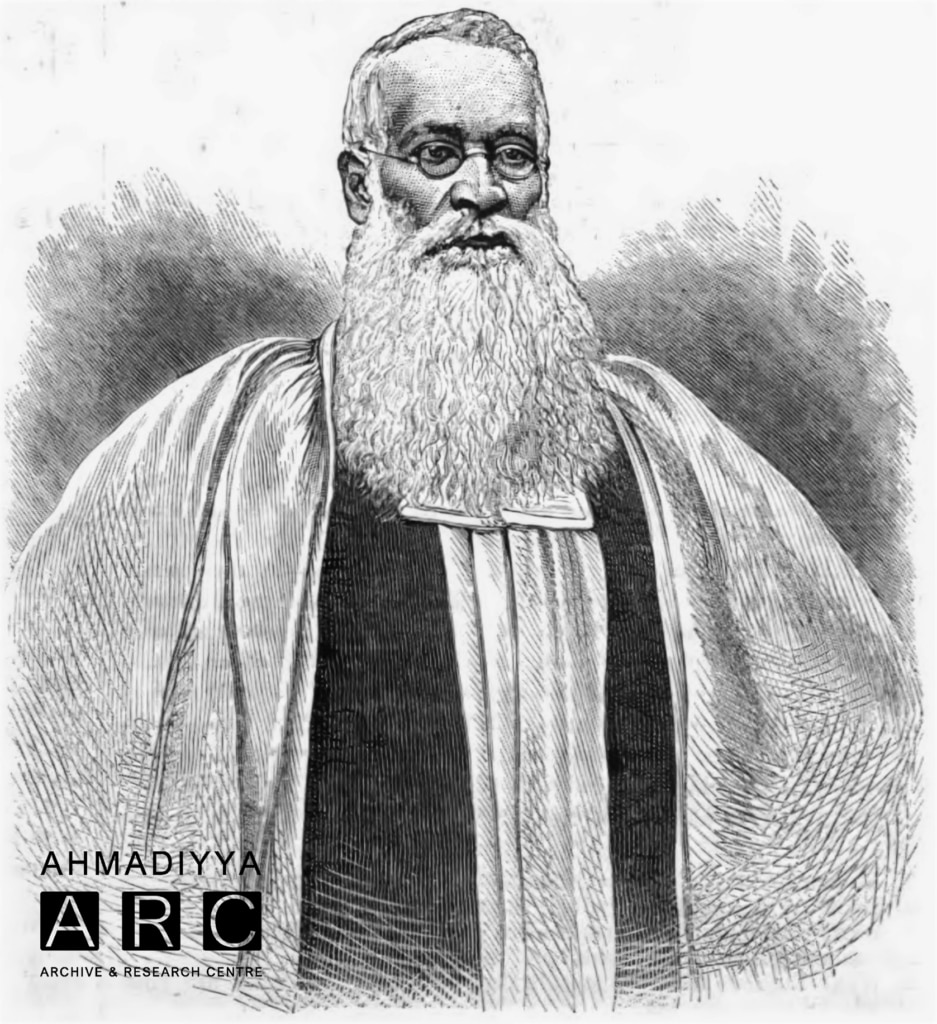

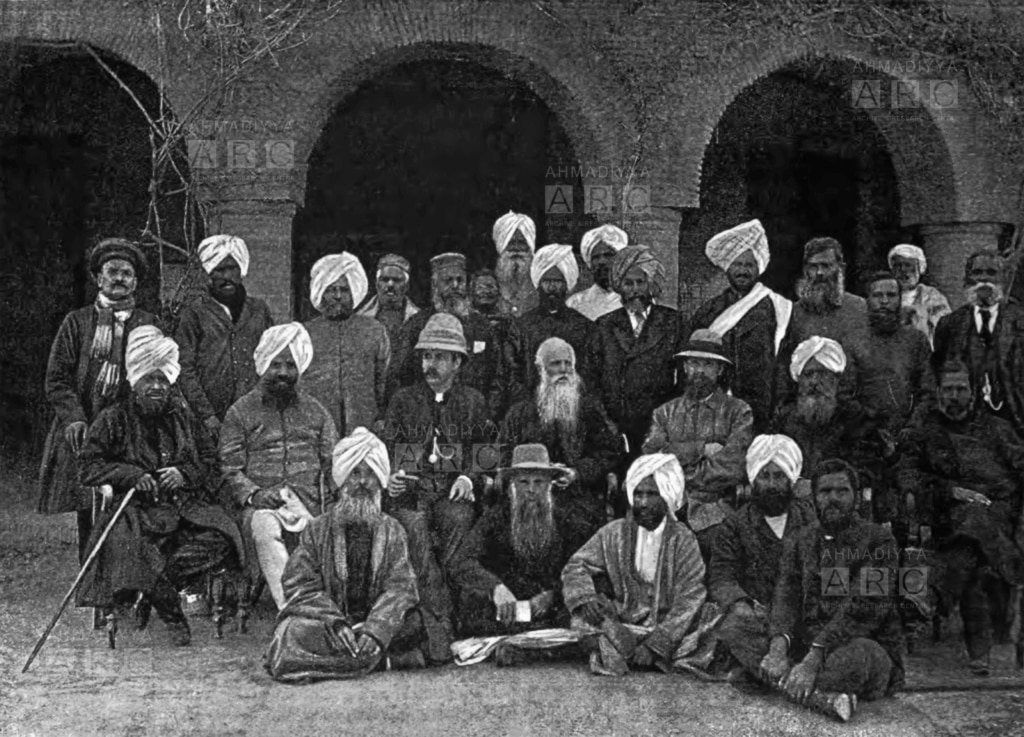

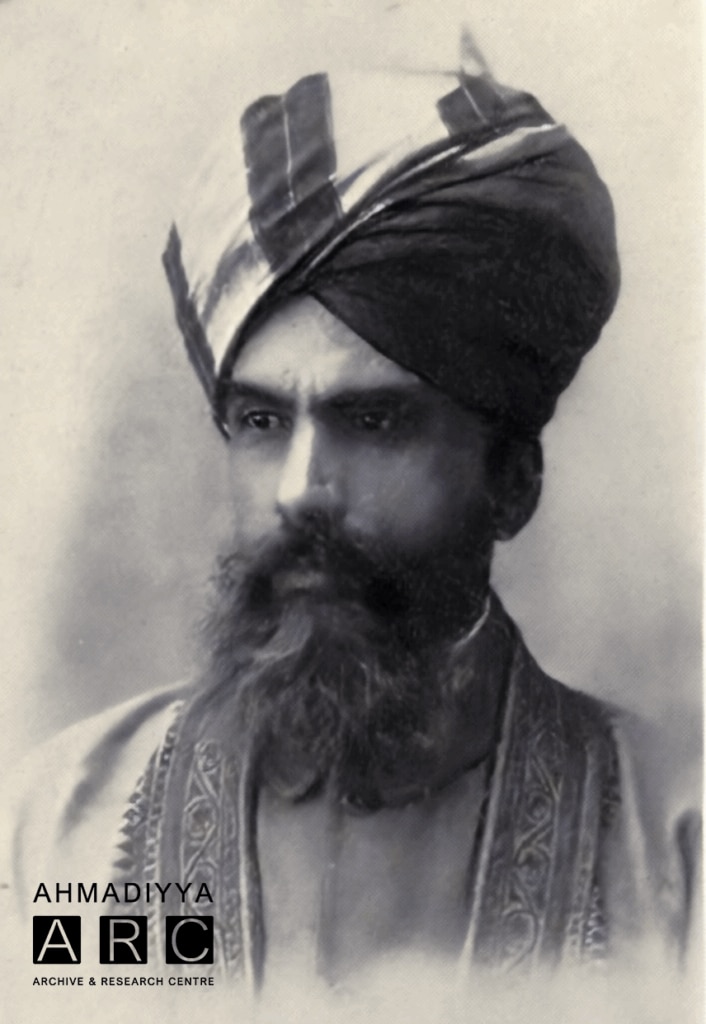

Born as a Sayyid and having grown up a Munshi, Abdullah Athim had served as a catechist in the Sindh Mission and was now an honorary priest. He was a retired Extra Assistant Commissioner and the head of a Christian village (possibly Clarkabad) and had recently (1888) taken up a prominent part in the first councils and formation of the Native Church in Lahore.40 It is from the very council’s meeting that the image above is taken from.

The Christians had their eyes fixated on the Punjab, and there was a genuine belief that this would be a stepping stone to turning India Christian. With a season General at its helm (Athim), an army was being prepared for war:

“[…] the transformation from heathen to Christian will be affected in India in less than half the time that separates Christ from Constantine.”41

The Great Controversy of 1893

By the early 1890s, the Christian army was adequately prepared for war, with Abdullah Athim at its helm. Its members included notable figures such as GL Thakur Das, Rev Imam-Ud-Din, and Rev Fateh Muhammad. However, they had yet to prove themselves to the rest of the world and had no significant accomplishments.

In 1893, tensions arose in Jandiala, where a local panda (religious teacher) firmly resisted the activities of the Christian medical mission.42 His opposition drew the attention of Dr Henry Martyn Clark in Amritsar. Seeing this as an opportunity, Dr Clark issued a public challenge to a religious debate. The Muslims of Jandiala were anxious and sought someone to represent them. Only Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas of Qadian accepted the challenge that no one else dared to face.43

Representatives from both parties gathered at Dr Clark’s residence to establish the rules for the upcoming debate. This debate would take place in Amritsar from 22 May to 5 June, 1893. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas of Qadian was the champion of the Muslims, and Abdullah Athim, retired EAC, was representing the Christians.45 The Promised Messiahas was to face this newly brewed army of the Christian clergy. That year, a Holy War took place in Punjab, India:

“Another unique feature was that the attack on Islam and the exposition of the truths of Christ were, for the first time in such a discussion, almost exclusively carried out by members of the Punjab Church. Indigenous Christians fought the battle, and this was keenly felt by the Mohammedans.”46

Fall of the Native Church

The debate raged on continuously for 15 days; the attendees were among some of the most influential people in India. Alas, towards the end, it became clear that the Christians had chosen to deal in bad faith.

“When our turn came, I must candidly confess our champion did not make the best of our case against Mohammedanism. Despite much advice…Mr. Atham pursued a course of his own…It was scarcely the type of war required.”47

Athim was under the illusion that he was untouchable and no power on earth could do him any harm. Unfortunately for him, this Balam had encountered the Mosesas of this age.

On the last day of the debate, 5 June 1893, a powerful prophecy was revealed by Allah the Almighty to the Promised Messiahas, which would shake the very core of Abdullah Athim and his Native Church:

“Nevertheless, I kept praying for this, and last night it was made clear to me after I had prayed to Allah the Almighty with great humility and beseeched Him to give a verdict in this matter and that we are humble servants and can do nothing without His verdict. So, He gave me this Sign in the form of a glad tiding that in this debate, whichever party from among the two is delib-erately adopting falsehood and abandoning the True God and is making a mere mortal into God, will be cast into Hell and utterly disgraced corresponding to the very days of this debate—in other words, taking one month for each day, meaning, within fifteen months—on the condition that he does not return to the Truth; and the one who is on the path of Truth and believes in the True God, his honour will be manifested through this; and at the time this prophecy will come to pass, some of the blind will begin to see, and some of the lame will begin to walk, and some of the deaf will begin to hear.”48

The debate and surrounding intricacies of the prophecy have been a longstanding topic of discussion. Much has already been said on the subject,49 and I encourage readers to explore the proceedings of the Holy War for further insights. Currently, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat is the only group widely distributing the Jang-e-Muqaddas50 (Holy War) to the public, perhaps an indicator of the conclusion of the Holy War. The reader may decide for themself.

Death or punishment?

Was death the punishment, or was it the wait? For one reason or another, the word of the Almighty, which Athim had once proudly denounced, lingered over him until July 1896. He was constantly on the run, traveling from Amritsar to his son-in-law, Judge George Lewis, in Ludhiana. Eventually, he barricaded himself in the mansion of another son-in-law, Rai Bahadur Maya Das, in Ferozepur.51

On 27 July 1896, a once arrogant and powerful man found himself utterly broken. He had long since lost the use of his right hand and had recently told his wife that he felt death was near. Just a few days later, he lost his voice as well. On his final day, he lay in bed beside his wife, pointed to the sky with his remaining left hand, and passed away.52

Death visited Athim twice: first in the physical sense and then in the realm of memory. After the clergy had said their farewells, Athim’s memory began to fade. His closest friend, Dr Henry M Clark, even undermined Athim’s performance at the debate. Nur Afshan would never again mention his name. The pride of the clergy had now turned into their greatest embarrassment, a far cry from when Rev Robert Clark once wrote that:

“No account of the Indian Christian congregation in Amritsar would be complete without some mention of Mr. Abdullah Athim.”53

I am afraid, Mr Clark, that many such accounts have been completed without mentioning Abdullah Athim.

Endnotes

1. Both sides of the 1893 debate published their own accounts. The Ahmadiyya Jamaat issued The Holy War (translation of Jang-e-Muqaddas), available online at alislam.org, recording the daily proceedings from 22 May to 5 June, 1893. On the Christian side, an edition of Jang-i-Muqaddas (The Holy War) was edited by Dr HM Clark, while Tanqih-i-Mubahisa (Report of the Discussion) was authored by GL Thakur Dass and serialised in the newspaper Nur Afshan. Rev Elwood Morris Wherry has referred to both Clark’s and Thakur Dass’s versions in his book The Muslim Controversy.

2. “Proselytising in India” was a section of the old Echo (London). ‘Proselytising’ refers to the act of converting someone from one religion or belief to another. Arthur J Dadson, a member of the Democratic Federation and a known socialist, wrote regarding the missionary work in India under this section on 20 August 1878. His letter sparked frenzy across the missionary circles, it kicked off a series of articles and letters being submitted to rebut Mr Dadson. One of his most quoted lines was: “I can truthfully assert that I never met with a respectable native-Hindoo or Mussulman-who had embraced the Christian religion.”

3. Anjam-e-Atham (The Death of Atham) was published after Atham’s demise on 27 July 1896 and includes the prophecy made about him during the 1893 debate, its explanation, and its fulfillment. Available in urdu here.

4. Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyyat, Vol. 1, p. 641

5. Rev Elwood Morris Wherry, The Muslim Controversy, “Being a Review of Christian Literature Written in the Urdu Language for the Propagation of the Christian Religion and the Refutation of Islam and India”. John P. Jones, Its Life and Thought, 1908, p. 335

6. Rev Abraham Matchett reports the name “Munshi Abdullah” in Proceedings of the Church Missionary Society for Africa & the East, 1855.

7. Church Missionary Intelligencer, 1897, p. 366

8. A Brahmin convert from Bengal, he had studied in Duff’s college. (Eugene Stock, The history of the Church Missionary Society, its environment, its men and its work, Vol/ 2, p. 204)

9. The Church Missionary Intelligencer of 1853 gives Medhu Sudun Seal’s personal account of Abdullah Athim’s conversion and he goes into great detail. (Church Missionary Intelligencer, 1853, p. 153)

10. Church Missionary Intelligencer, 1897, p. 366

11. Church Missionary Intelligencer, 1853, p. 153

12. A students’ history of education in India (1800-1973), p. 18

13. Rev Abraham Matchett was in charge of the mission in Karachi and baptised Abdullah in 1853.

14. Church Missionary Intelligencer 1853, pp. 153-156 and also verified by Rev Abraham Matchett in CMS Missionary Register, 1855, “India within the Ganges”, pp. 346-349

15. Church Missionary Intelligencer, 1853, pp. 153-156

16. Church Missionary Intelligencer, 1853, p. 154

17. Athim or Atham means ‘sinner’. He replaced his old name Adbullah and christinised it to ‘Ubaid-Yah’. ‘Ubaid’ for ‘abd’ and ‘Jahweh’ for ‘Allah’.

18. The Church Missionary Gleaner New Series, 1853, Vol. 3, p. 125

19. Ibid., p. 123

20. Sir William Muir KCSI was a Scottish orientalist and colonial administrator, later Principal of the University of Edinburgh and Lieutenant-Governor of the North-Western Provinces, India. Author of Life of Mahomet and The Mohammedan Controversy.

21. Life of Professor Yesudas Ramchandra of Delhi, pp. 47-53

22. Chand Su’alat, p. 8

23. The Book and the Prophet, “The Contribution of Indian Christians to the Muslim-Christian Debate of the 19th Century”, p. 156

24. See, front cover of Abdullah Athim’s poetic works given above.

25. Bombay Gazette, 12 February 1855

26. Proceedings of the Church Missionary Society for Africa & the East, 1855, p. 74

27. Church Missionary Intelligencer, 1897, p. 367

28. One hundred years: being the short history of the Church Missionary Society, p. 80

29. The missions of the CMS & CEZMS in the Punjab and Sindh, pp. 235-236

30. Indian Statesman, 3 February 1876

31. The missions of the CMS & CEZMS in the Punjab and Sindh, pp. 43-44

32. Civil & Military Gazette (Lahore), 23 April 1873

33. Civil & Military Gazette (Lahore), 19 November 1880

34. Civil & Military Gazette (Lahore), 07 August 1882

35. Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, 1884, p. 312.

36. The Church missionary record, 1860-1861, pp. 179-180

37. Church Missionary Intelligencer and Record, 1884, p. 312

38. Mohammedan converts to Christianity in India, p. 8

39. The Church missionary review, Vol. 34, 1883. p. 691

40. Ibid., p. 691

41. Widnes Examiner, 1 April 1893

42. Proceedings of the Church Missionary Society, 1894/95, p. 167

43. The Sunday at home: a family magazine for Sabbath reading, 1893/94, p. 351

44. Dr Clark reports that: “An enterprising Mohammeddayscontinuouslyan publisher in Amritsar issued the verbatim reports daily, and it was a sight to see how the papers were bought up. The street in which the press is situated was a mass of heads, waiting for the daily issue. The first edition went like wild-fire; a second has now also been exhausted.” This cover is from the second edition. (The Sunday at home: a family magazine for Sabbath reading, 1893/94, p. 351)

45. See, the cover page of Jang-e-Muqaddas (The Holy War]) above.

46. Proceedings of the Church Missionary Society, 1893/94, p. 120

47. Church Missionary Intelligencer, 1894, p. 99

48. Jang-e-Muqaddas, pp. 287-288

49. The Holy War: The great debate between Christians & Muslims in the subcontinent, available on reviewofreligions.org.

50. Available online at alislam.org, recording the daily proceedings from 22 May to 5 June, 1893.

51. Letter from Dr Martyn Clark presented in the article by Asif M Basit, The Holy War, “The great debate between Christians & Muslims in the subcontinent”, reviewofreligions.org.

52. Church Missionary Intelligencer, 1897, p. 367

53. The missions of the CMS & CEZMS in the Punjab and Sindh, p. 43