Iftekhar Ahmed, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre

It strikes me that truth has a curious way of forcing itself upon even those who wish to deny it. This becomes especially clear when religious opposition meets undeniable scholarly excellence, creating what we might call a crisis of knowledge: the need to praise and condemn at the same time, to recognise brilliance whilst rejecting its source, to affirm quality whilst denying its legitimacy.

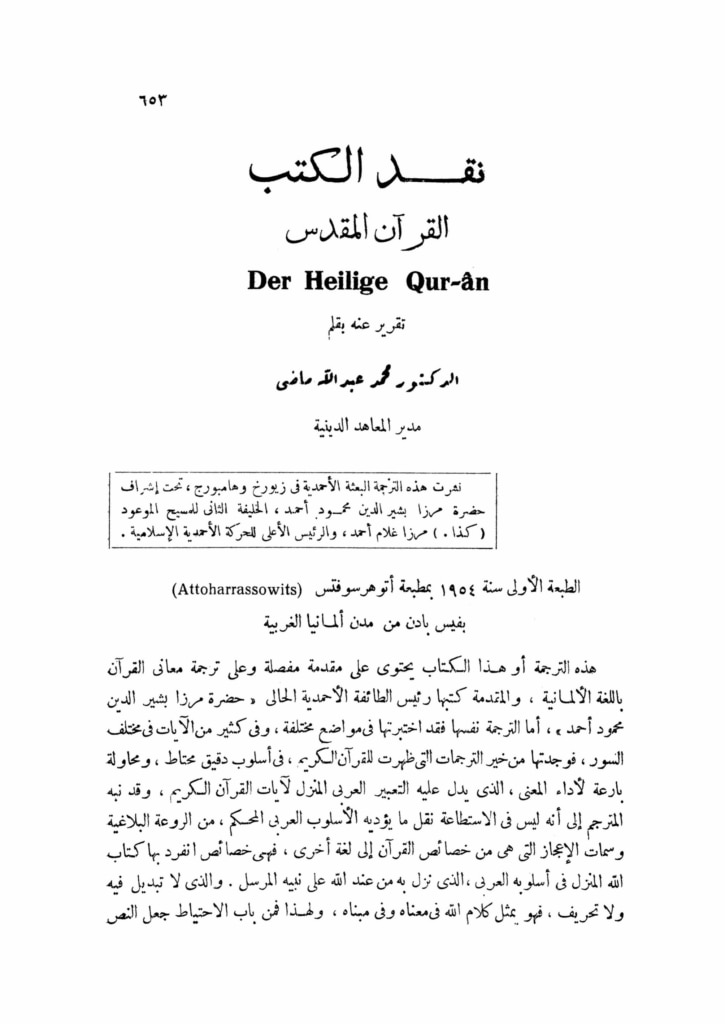

Such a crisis unfolds with remarkable clarity in Dr Muhammad Abdullah Madi’s 1959 review of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat’s first German translation of the Holy Quran, published in Majallat al-Azhar,1 the official journal of al-Azhar University. The reviewer’s credentials make this document particularly significant: Dr Madi was no peripheral figure but stood at the apex of Islamic scholarly authority. Born in 1903 in Egypt’s Beheira province, he had memorised the Quran in his village before studying under luminaries like Mahmud Shaltut – later President of Al-Azhar – at the Alexandria Institute. His educational trajectory took him from teaching at that same institute in 1930 to the universities of Berlin and Hamburg, where he earned his doctorate with distinction in 1936, specialising in Islamic history and Eastern studies. By the time of this review, he held the position of Director General of Religious Institutes, having served as Professor of History at Al-Azhar’s Faculty of Theology since 1951, and would later become Deputy of Al-Azhar itself by presidential decree in 1962.

Here, then, we have not merely any reviewer but one who represented the institutional authority of Al-Azhar – that millennium-old bastion of Sunni orthodoxy. His fluency in German, acquired during his years in Berlin and Hamburg, equipped him to assess the translation with scholarly precision. His position at the summit of the Islamic educational establishment meant his words carried institutional weight. Yet this very authority makes his review’s internal contradictions all the more revealing – a text attempting to sustain mutually exclusive positions whilst appearing coherent.

The architecture of reluctant praise

Dr Madi’s review opens with what appears to be a straightforward scholarly assessment. He examines the 1954 translation – Der Heilige Qur’an – published under the supervision of Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra, whom he cannot name without the parenthetical qualifier

(كذا)

“sic”

when referring to him as the Second Khalifa of the Promised Messiahas. Yet this very punctuation mark, this typographical grimace, reveals the central tension running throughout the review: the need to acknowledge authority whilst denying its legitimacy.

What follows is extraordinary in its surgical precision of praise. Dr Madi declares after testing various passages across different Surahs:

فوجدتها من خير الترجمات التى ظهرت للقرآن الكريم

“I found it among the best translations of the Holy Quran that have appeared.”

Coming from someone of his linguistic competence and institutional standing, this assessment carries considerable weight. Not simply acceptable, not simply adequate, but “among the best.” The superlative cannot be retracted. It stands as testimony.

He continues, noting the translation’s

أسلوب دقيق محتاط

“precise and careful style”

and its

محاولة بارعة لأداء المعنى

“skilful attempt to convey the meaning.”

These are not grudging concessions but professional assessments from one whose entire career had been devoted to Islamic scholarship. The accumulated adjectives – precise, careful, skilful – build a fortress of quality that cannot later be demolished by theological disagreement.

The test of jihad: Where prejudice meets precision

Most revealing is Dr Madi’s specific examination of verses relating to jihad and fighting in the way of Allah. Here, one suspects, he hoped to find his smoking gun – evidence of Ahmadi “distortion” that would justify wholesale dismissal. He approaches these verses with explicit suspicion,

بحثاً عما عساه يكون قد ضمن الترجمة مما يتصل بما يراه الأحمدية في الجهاد

“searching for what might have been included in the translation relating to Ahmadi views on jihad.”

The Ahmadi position on jihad – emphasising its spiritual and defensive dimensions whilst rejecting aggressive warfare – has long been a point of theological contention. Dr Madi clearly expected to find this interpretation smuggled into the translation, providing grounds for scholarly and religious objection. Instead, he encounters something that confounds his expectations:

فوجدتها سليمة لا تتضمن أدنى الإشارات إلى هذا الذي كنت أخشى أن تتضمنه

“I found them sound, not containing the slightest indication of what I feared they would contain.”

This admission from a scholar of his calibre is striking not for what it says but for what it demonstrates about the review’s underlying structure. Dr Madi approached the text actively, searching for flaws, bringing to bear all his scholarly expertise to hunt for ideological contamination in the most controversial areas. His failure to find such flaws – indeed, his public admission of this failure in Al-Azhar’s own journal – establishes the translation’s integrity more convincingly than any positive endorsement could achieve.

The Introduction: “Wonderful Islamic research”

The review’s treatment of Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad’sra extensive Introduction to the Study of The Holy Quran represents perhaps its most striking contradiction. Dr Madi, whose own doctoral dissertation had involved rigorous textual analysis and historical research, methodically catalogues the Introduction’s contents, listing its comprehensive treatment of Islamic theology, Quranic sciences and spiritual philosophy. His assessment:

بحوث إسلامية رائعة

“wonderful Islamic research.”

From someone like him, the adjective

رائعة

“wonderful”, “splendid”, “magnificent”

exceeds mere adequacy. It expresses genuine scholarly admiration.

He notes how the Introduction addresses humanity’s need for divine guidance, the corruption of previous scriptures, the preservation of the Quran, prophecies fulfilled, the nature of prayer, fasting, pilgrimage, charity, women’s rights, economic systems, the soul, divine attributes – a comprehensive presentation of Islamic thought. Each topic, he acknowledges, receives sophisticated treatment. The phrase

في ثوب وإطار إسلامى

“in an Islamic garment and framework”

confirms that this representative of Al-Azhar recognises this as authentically Islamic scholarship, not some syncretic innovation.

Yet embedded within this praise lies the review’s central tragedy. Dr Madi – recipient of the Order of the Republic First Class for his services to Islamic education – cannot simply acknowledge excellence; he must qualify it with hypothetical conditions. If only – the perpetual subjunctive of sectarian prejudice – if only the author were not who he is, what beautiful things he writes! This hypothetical framing imprisons him – he can acknowledge excellence but never accept it.

The volta: “But!”

The review’s pivot arrives with theatrical emphasis:

ولكن!

“But!”

Dr Madi even repeats it:

نعم ولكن مع الأسف الشديد

“Yes, but with great regret.”

This linguistic performance – the affirmation followed by negation, the “yes, but” structure – reveals the review’s impossible position. Great regret indeed, but regret for what? For the excellence that must be rejected? For the truth that must be denied? Or for the reviewer’s own inability to transcend the sectarian boundaries that his position at Al-Azhar required him to maintain?

The final section of the Introduction, discussing the Promised Messiahas, triggers Dr Madi’s institutional antibodies. Suddenly, all previous praise becomes irrelevant. The “wonderful Islamic research” transforms into

وضع السم فى العسل

“placing poison in honey.”

The metaphor illuminates much: even the Deputy of Al-Azhar acknowledges the honey’s sweetness whilst declaring it contaminated. Yet honey’s sweetness remains honey’s sweetness, regardless of what one claims has been added to it.

The extraordinary conclusion

The review’s conclusion represents a masterpiece of cognitive dissonance. After praising the translation as among the best available, after finding no fault even where he most expected it, after acknowledging the Introduction’s comprehensive excellence, Dr Madi calls for the book’s confiscation:

ينبغى مصادرته

“it should be confiscated.”

Yet even here, he cannot maintain consistency. He immediately qualifies:

وحبذا لو كان من المستطاع فصل هذا الجزء الأخير

“How wonderful if it were possible to separate this last section.”

He wishes to preserve the excellence whilst removing what challenges Al-Azhar’s theological assumptions. The tragedy is that he recognises the value –

لكان فيه خير كثير

“there would be much good in it”

– but his institutional position prevents him from accepting the source.

The inadvertent testimony

What Dr Madi achieves, despite himself, is to provide one of the most compelling testimonies to Ahmadi scholarship from within the Sunni establishment itself. His review, published in Al-Azhar’s official journal and carrying all the weight of his institutional authority, intended as a warning, becomes a witness. His very inability to find fault where he desperately sought it, his compulsion to acknowledge excellence even whilst calling for suppression, his recognition of authentic Islamic scholarship even whilst denying the authors’ Islamic credentials – all serve to highlight the intellectual poverty of sectarian prejudice when confronted with genuine achievement.

The significance of this testimony cannot be overstated. Here was not some marginal figure but one who had ascended through every level of Islamic scholarly authority. His training in both traditional Islamic sciences and modern Western academia prevents him from simply dismissing what his eyes read and his mind comprehends. He must acknowledge quality because quality exists independently of his theological preferences or institutional obligations.

This creates a document of extraordinary historical importance: evidence that even at the height of anti-Ahmadi sentiment in the Arab world, even from the very pinnacle of Sunni religious authority, even from one whose entire career was built within orthodox institutions, excellence could not be denied. The translation’s precision, the Introduction’s comprehensiveness, the scholarship’s authenticity – all had to be acknowledged by Al-Azhar’s own Deputy, even if immediately followed by calls for suppression.

The universal structure illuminated

Dr Madi’s review illuminates a universal pattern in religious discrimination: the simultaneous recognition and rejection of the other’s humanity, scholarship and spiritual insight. It is not ignorance that drives such prejudice but precisely the opposite – the recognition of excellence that threatens established hierarchies. The call to confiscate emerges not from finding flaws but from finding none. The demand for excision comes not from discovering poison but from tasting honey.

The great irony – and Dr Madi seems partially aware of this – is that his review serves the opposite of its intended purpose. By so thoroughly documenting the translation’s excellence whilst simultaneously calling for its suppression, this representative of orthodox Islam provides future generations with evidence of both Ahmadi achievement and establishment prejudice. His review, published in Al-Azhar’s own pages, becomes a monument to the very scholarship it attempts to deny.

Perhaps most poignantly, Dr Madi’s wish to separate the final section and preserve the rest demonstrates a deep truth: even from his position at the summit of Sunni orthodoxy, he recognises that the Islamic scholarship is genuine, the Quranic translation authentic, the theological insights valuable. His objection is not to the content but to its source – a position that indicts not the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat but the institutional framework that required such intellectual contortions from even its most educated representatives.

The review thus stands as inadvertent testimony from the highest echelons of Islamic authority – evidence against its own position, witness to what it attempts to deny, proof of the very excellence it must reject. In attempting to warn against Ahmadi scholarship, Dr Madi has instead preserved for posterity one of its most compelling vindications: that even Islam’s most authoritative institutions, when confronted with Ahmadi reality rather than its caricature, cannot help but recognise its truth.

Endnotes

1. Muhammad Abdullah Madi, “Al-Qur’an al-Muqaddas: Der Heilige Qur-ân,” Majallat al-Azhar, Vol. 30, no. 8 (Sha‘ban 1378/February 1959), pp 653-659.