Ata-ul-Haye Nasir, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre

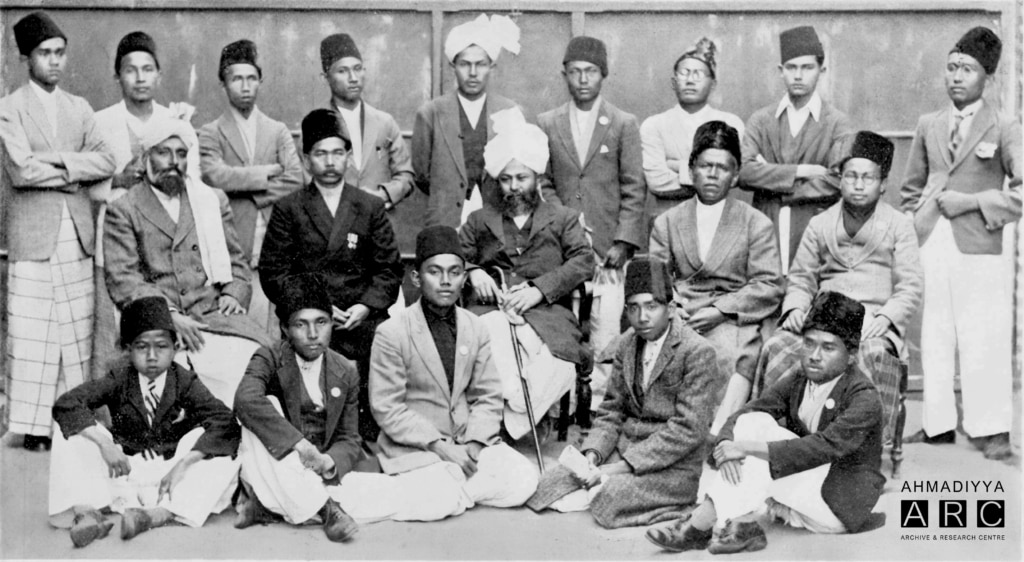

In the early 1920s, four Sumatran youth – Maulvi Abu Bakr Ayub Sahib, Maulvi Ahmad Nuruddin Sahib, Maulvi Zaini Dahlan Sahib and Haji Mahmud Sahib – came to India for their religious education. In August 1923, Allah’s decree drew them to Qadian after their visit to Calcutta, Lucknow and Lahore.

These students met with Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra and requested for their religious education and training to be arranged. Huzoorra accepted the request and arranged for their education. After being convinced about the truthfulness of the Promised Messiahas, they accepted Islam Ahmadiyyat.

After swearing allegiance in Qadian, the youth preached to their relatives back home through letters, thus paving the way for the propagation of Ahmadiyyat to those islands.

On Hazrat Musleh-e-Maud’sra return from his tour of Europe in 1924, several receptions were held in his honour. The Sumatran students also arranged a tea party on 29 November 1924 and spoke to Huzoorra in regard to preaching the message of Ahmadiyyat in their homeland.1

Hence, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra sent Hazrat Maulvi Rahmat Alira to spread the message of Islam Ahmadiyyat to the people of the Dutch East Indies – present day Indonesia. He departed from Qadian on 17 August 1925, exactly 100 years ago.2

This article will focus on presenting the historical records about the Ahmadi missionary’s arrival in the islands, his preaching activities in the early years and a glimpse of the press coverage.

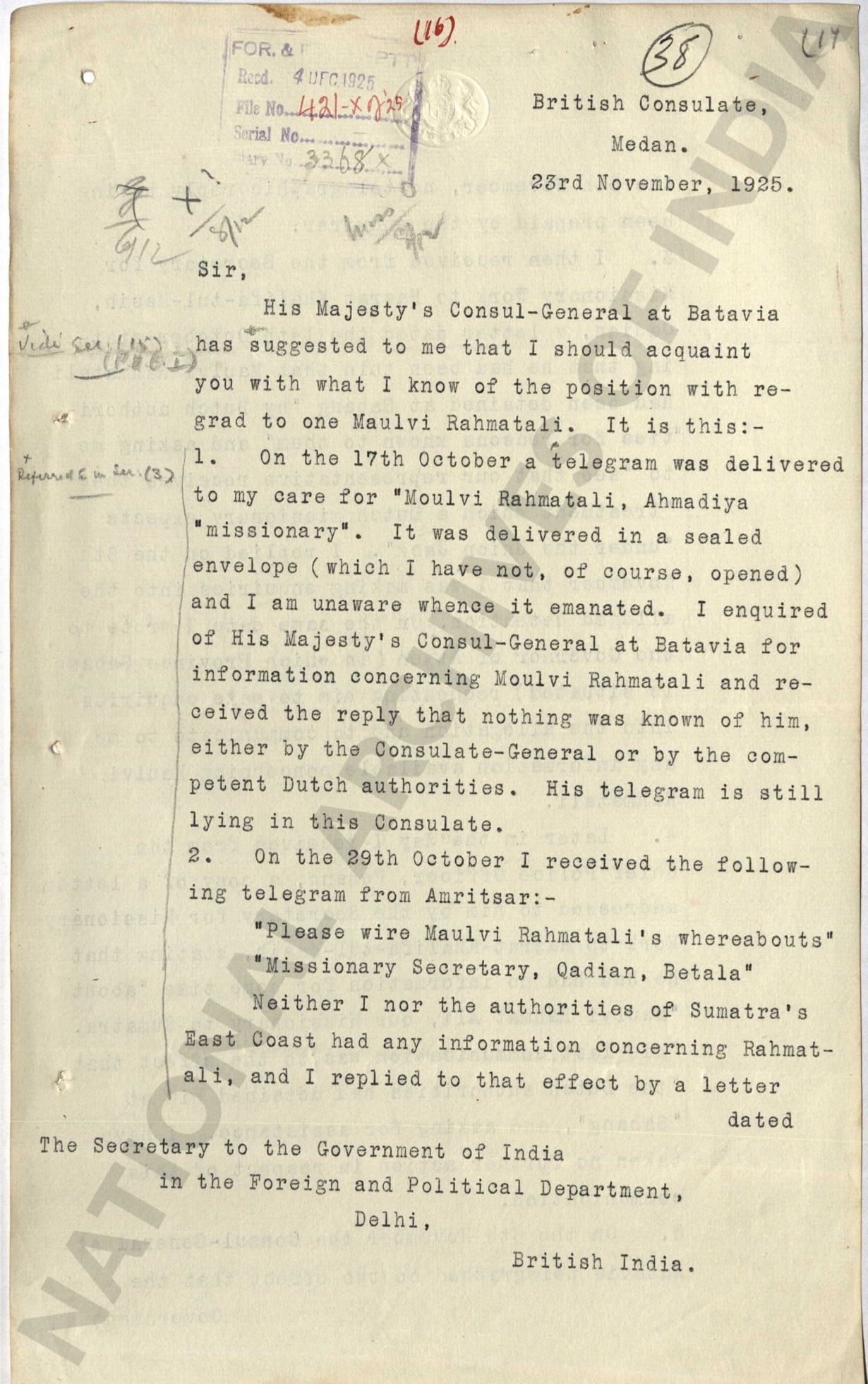

Departure, rumours and a series of telegrams

Since Hazrat Maulvi Rahmat Ali’sra departure from Qadian, no information had yet reached about his well-being and rumours began circulating that he had been detained by the Dutch authorities – who were governing Indonesia at the time.

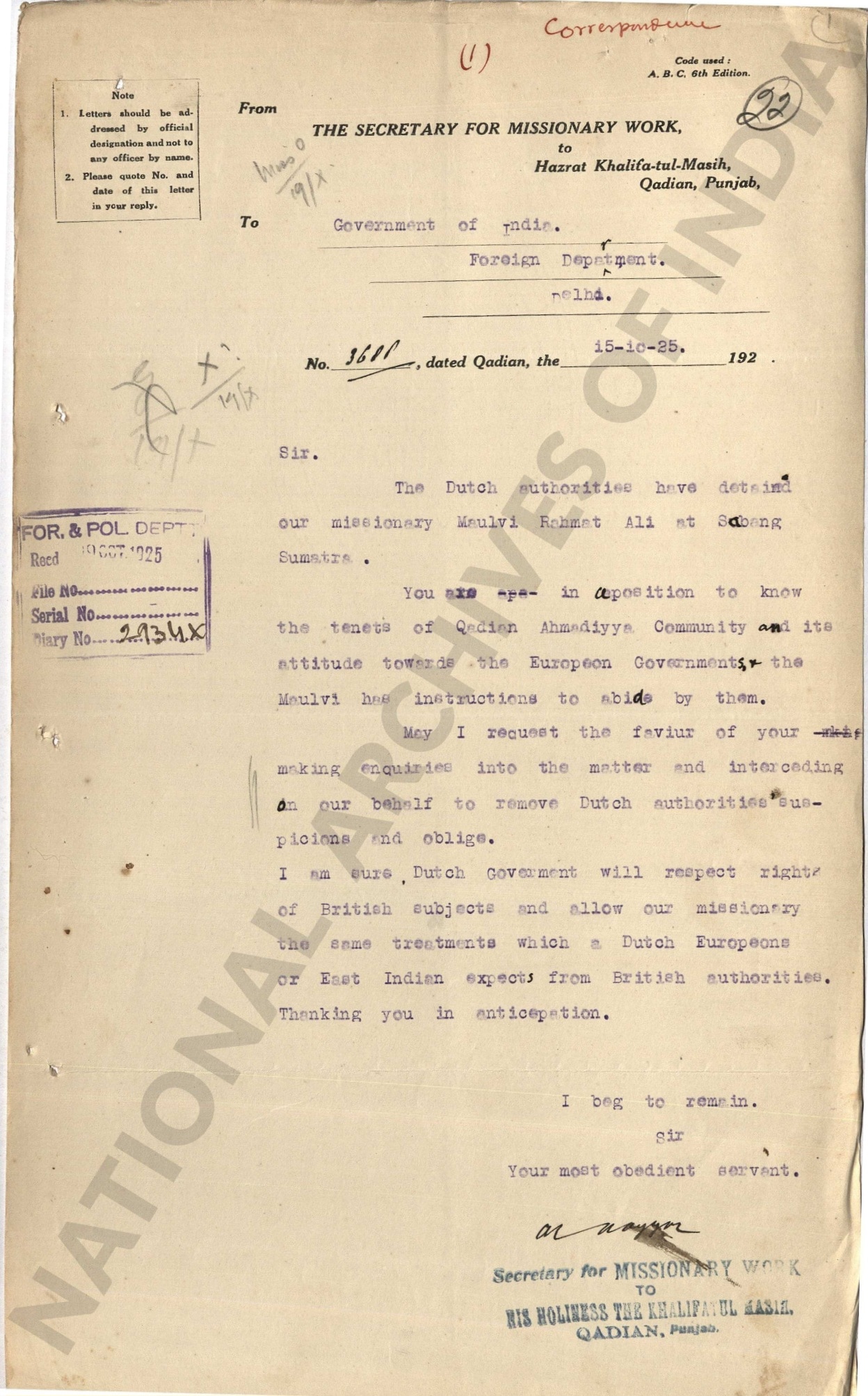

Hence, on 15 October 1925, a letter was sent to the Foreign and Political Department of the British Indian Government by Hazrat Maulvi Abdur Rahim Nayyarra, who raised concerns about the rumours, stating that the “Dutch authorities have detained our missionary Maulvi Rahmat Ali at Subang Sumatra.”3

He expressed his hope that the Dutch Government will respect the rights of British subjects which a Dutch European or East Indian expects from British authorities.4

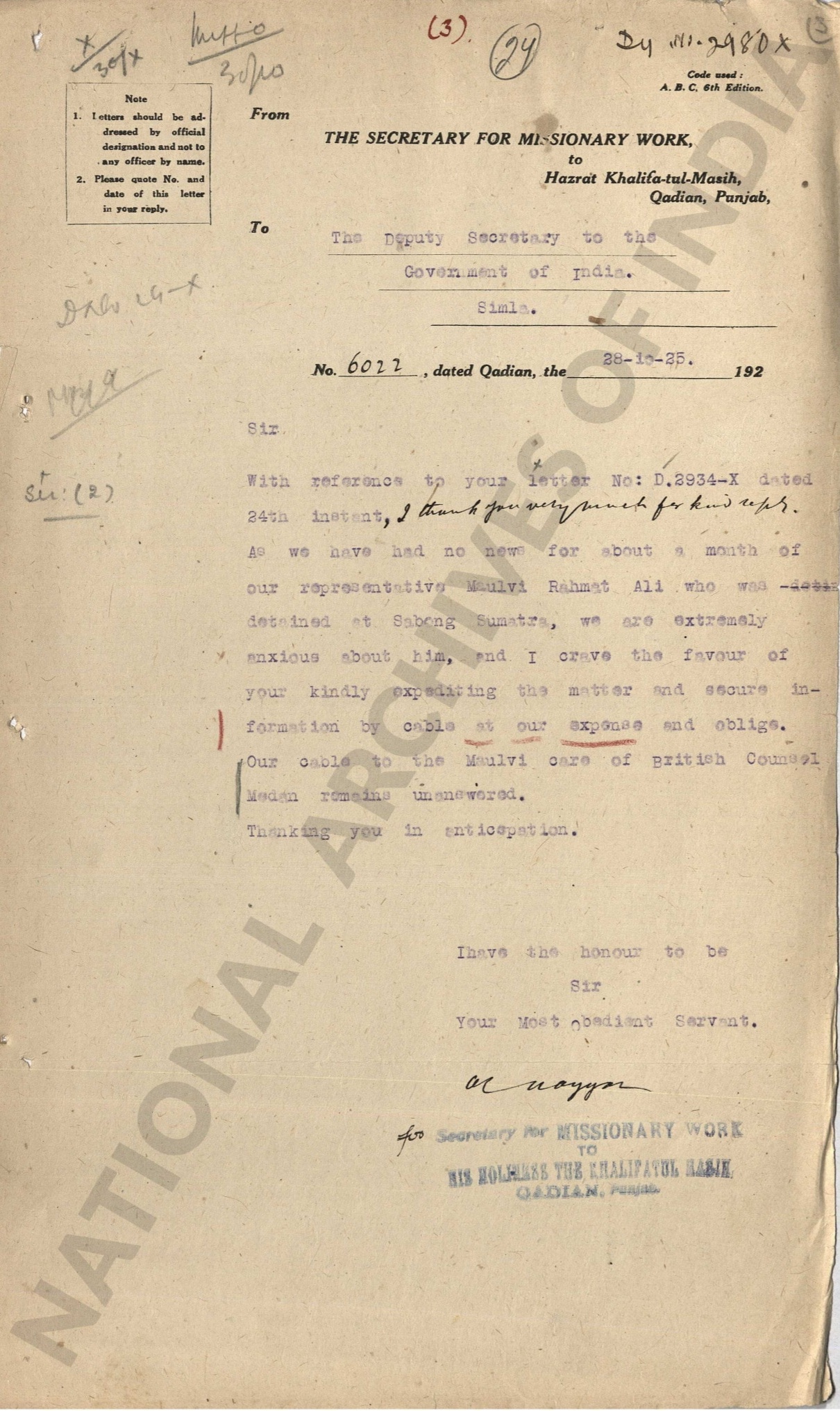

A response was received on 24 October, stating that “inquiries are being made into the matter”5 and the acknowledgement of this reply was sent from Qadian on 28 October wherein the authorities were further informed that a telegram to the missionary remained unanswered.6

Official records also suggest that – due to some misunderstanding or their usual security protocols – the British officials began an enquiry about the missionary, initiating a long correspondence between the Foreign and Political Department, Home Department, Director Intelligence Bureau (DIB) and officials in the Dutch East Indies. However, on 14 November 1925, a telegram from the Foreign and Political Department to the British Consul-General in Batavia declared that “it was believed that deputation was politically harmless.”7

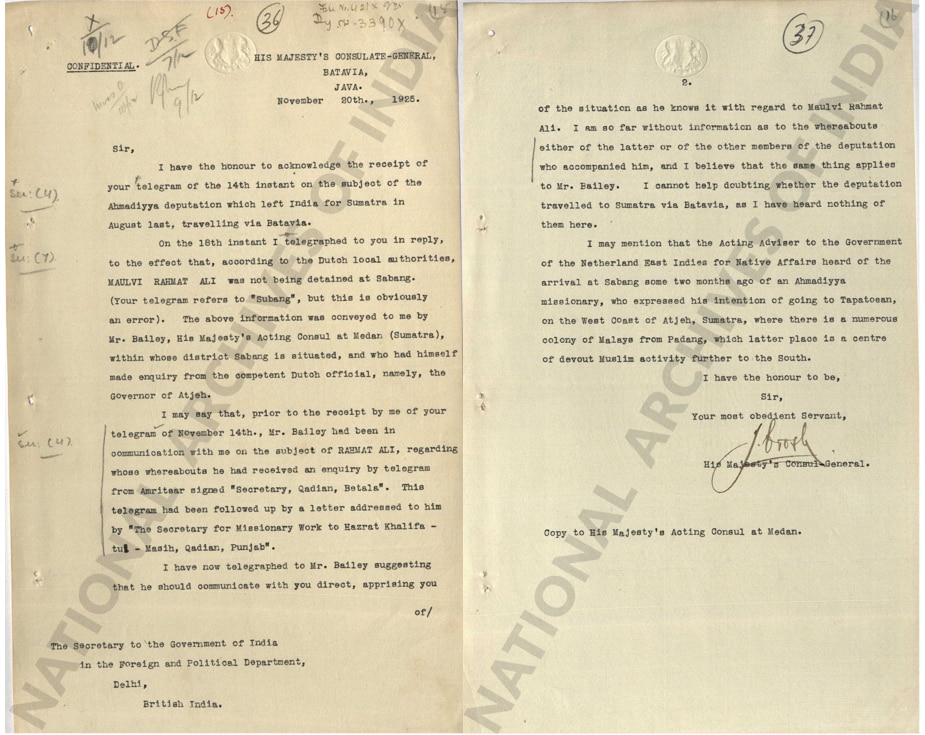

The above-quoted telegram further mentioned the Jamaat’s concerns about the missionary’s safety and thereafter, a reply from the Consul-General stated that “according to the local authorities, person named is not being detained at Sabang.”8 This response was then conveyed to Qadian.

The British Consul-General wrote to the Foreign and Political Department, on 20 November, mentioning further details including a letter from Qadian that was sent on behalf of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIra – addressed to the missionary. The British official also shared information about the whereabouts of the missionary.

Mentioning all these details, the British Consul-General stated that the Acting Consul-General at Medan, Mr Bailey, had been in communication with him on the subject of Rahmat Ali Sahibra, regarding whose whereabouts Mr Bailey “had received an enquiry by telegram from Amritsar signed ‘Secretary, Qadian, Betala’”. This telegram, according to the British Consul-General, had been followed up by a letter addressed to Mr Bailey from “The Secretary for Missionary Work to Hazrat Khalifatul Masih, Qadian, Punjab.”

The British Consul-General continued by mentioning that the Acting Adviser to the Government of the Dutch East Indies for Native Affairs “heard of the arrival at Sabang some two months ago of an Ahmadiyya missionary, who expressed his intention of going to Tapatoean, on the West Coast of Atjeh, Sumatra, where there is a numerous colony of Malays from Padang, which latter place is a centre of devout Muslim activity further to the South.”9

Thereafter, on 23 November 1925, the Acting Consul-General at Medan sent a detailed report to the Foreign and Political Department in regards to the enquiry on Hazrat Maulvi Rahmat Alira. He mentioned the telegrams received from Qadian on 17 and 28 October. He went on to mention further correspondence he had with the Jamaat and the government officials, regarding the same matter.

On 4 December, the British Consul-General in Batavia informed the Government that Rahmat Ali Sahibra was in Tapatoean. The British official stated that according to the latest information received by the Dutch authorities, Maulvi Rahmat Ali Sahibra arrived at Tapatoean on 2 October and intended to proceed to Padang within a month’s time.10

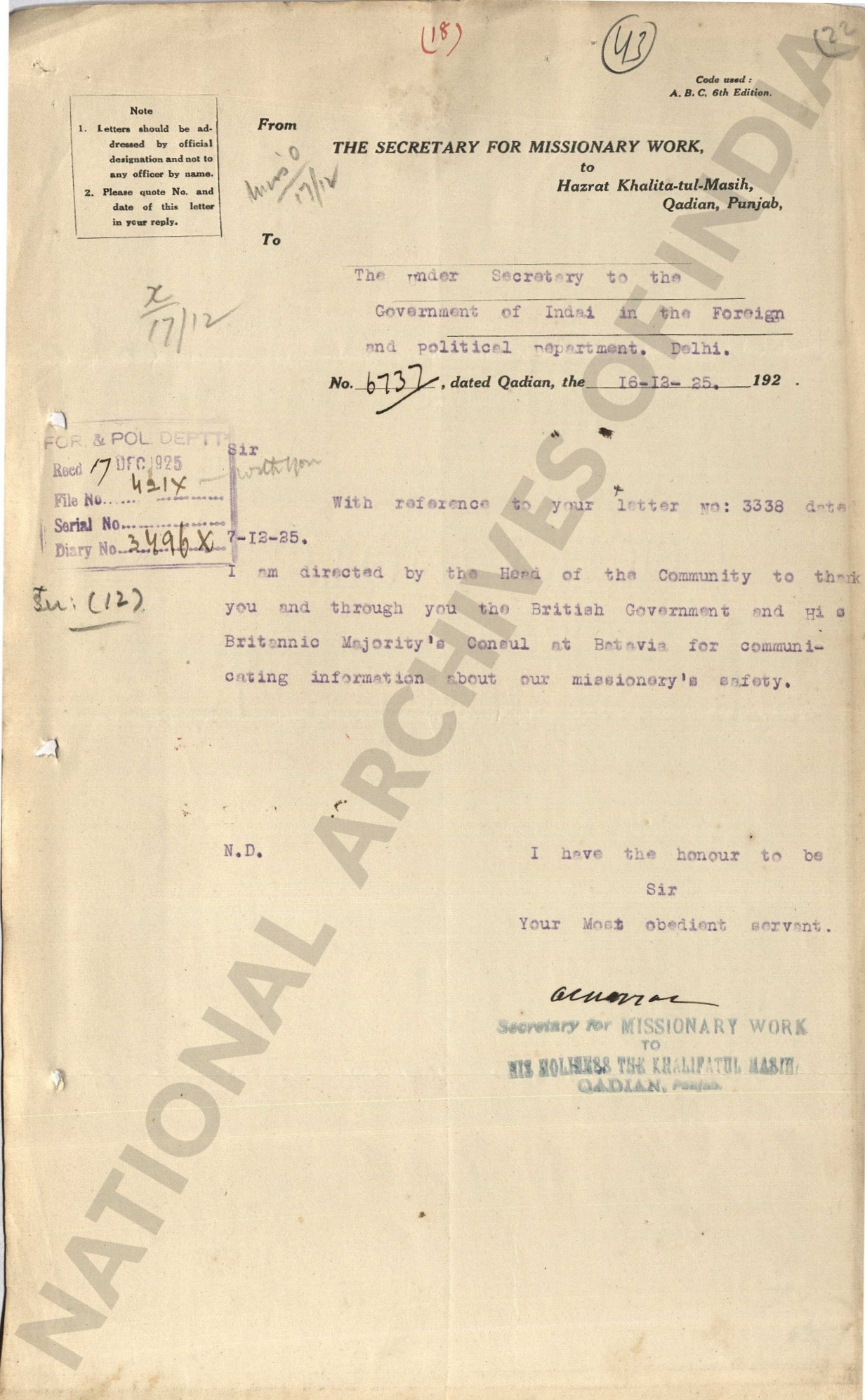

This message was conveyed to Qadian on 7 December. In response, a letter of thanks was sent to the Under Secretary to the Government of India, on behalf of Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra, stating:

“I am directed by the Head of the Community to thank you and through you to the British Government” and the British “Consul at Batavia for communicating information about our missionary’s safety.”11

During this ongoing correspondence between the government officials, it was stated that “Enquiries made by the D.I.B. have elicited that there is nothing politically objectionable against Rahmat Ali.”12

A comprehensive personal introduction to Maulvi Rahmat Ali Sahibra was included in the official correspondence which stated that “he is reported to take no interest in politics.”13

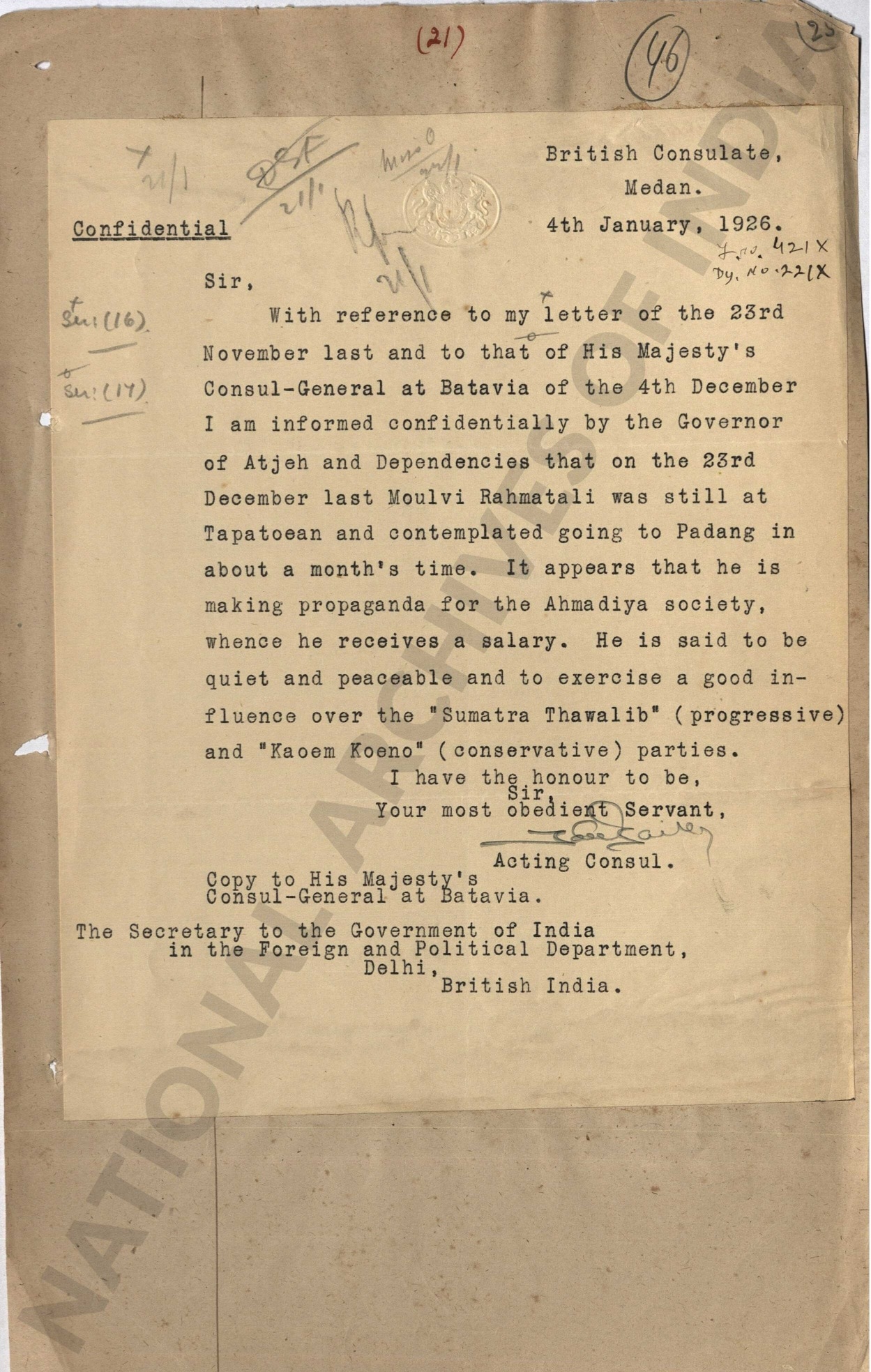

On 4 January 1926, the Acting Consul-General at Medan informed the Government about the activities of Maulvi Rahmat Ali Sahibra, stating:

“It appears that he is making propaganda for the Ahmadiya society, whence he receives a salary. He is said to be quiet and peaceable and to exercise a good influence over the ‘Sumatra Thawalib’ (progressive) and ‘Kaoem Koeno’ (conservative) parties.”14

Sowing the seed in the islands

Upon reaching the islands – now Indonesia – Maulvi Rahmat Ali Sahibra propagated the message of Islam Ahmadiyyat with great zeal, as a result of which Allah the Almighty blessed his efforts with good results.

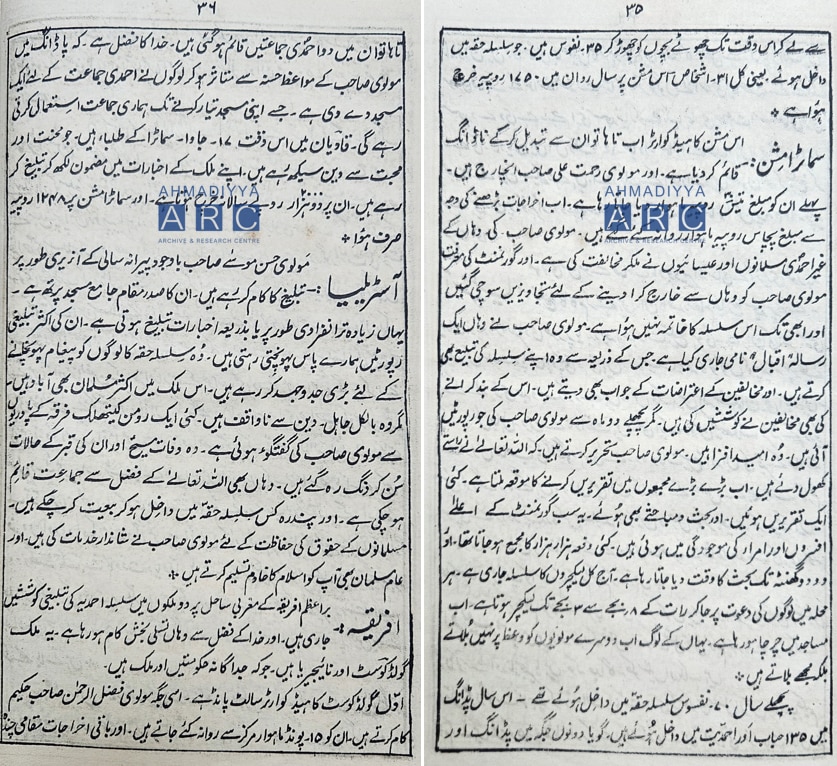

During a speech at the Jalsa Salana 1925, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra informed the Jamaat about the establishment of Ahmadiyyat in Sumatra and stated that around 15 people had accepted Ahmadiyyat within a few days.15

During the 1927 Majlis-e-Shura, held on 15-17 April, a summarised report of the Indonesian Mission was presented. According to this report, the headquarters had been changed from Tapak Tuan to Padang and the missionary had to face severe opposition from the non-Ahmadi Muslims and Christians. The opponents were making all possible efforts to urge the government to expel him from the country. The missionary reported that he delivered various speeches in large gatherings and discussions were also held, attended by high-ranking government officials and dignitaries as well.

In 1926, the number of new converts was 70, while during the year 1927 – thus far – 150 more people had accepted Ahmadiyyat in Padang. By that time, there were 17 students from Java and Sumatra who were attaining religious knowledge in Qadian and writing articles for the newspapers of their country as well.16

The above-quoted Shura report also mentioned a periodical called “Iqbal”. Its full name was Iqbaloel Haq. In a previous speech, at the Jalsa Salana 1926, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra had stated that a distinguished local non-Ahmadi Muslim launched a periodical at his own expense and invited Ahmadis to publish articles about Ahmadiyyat in that periodical.17

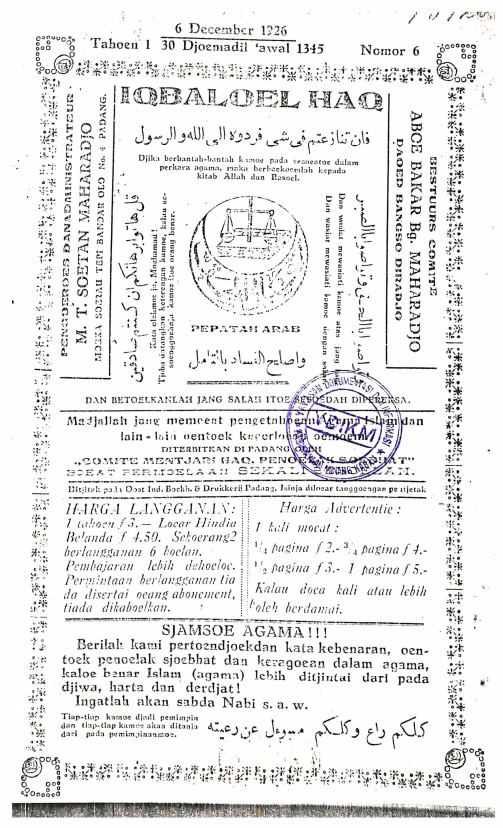

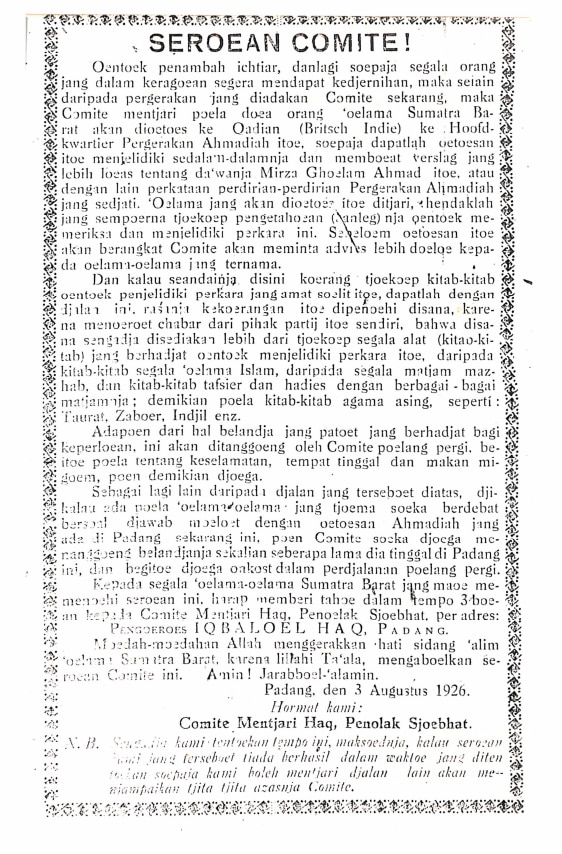

We learn from the Indonesian press that considering the increasing hostility shown by the opponents of the Jamaat, a committee was established with the cooperation of some good-natured non-Ahmadi Muslims. Its aim was to invite the non-Ahmadi scholars to dialogue and to resolve the differences in a peaceful manner by presenting theological arguments. This committee was called “Mentjari Hak Penoelak Sjoebahat”. The committee launched the periodical Iqbaloel Haq in July 1926.

In addition to the articles by Ahmadis, articles by many non-Ahmadi scholars were published in which they presented their arguments against the Ahmadiyya beliefs. In the 3 August 1926 issue, an announcement from this committee was published, outlining a plan to send a delegation of non-Ahmadi scholars to Qadian so that they could themselves thoroughly get to know the beliefs of Ahmadiyyat and claims of the Promised Messiahas.

A report from Maulvi Rahmat Ali Sahibra stated:

“The Ulema are bitterly opposing our movement here. They are trying to keep the people away from us by all sorts of means. Some of them reported us to the Government, saying that we believed in a bloody Mahdi who proclaims a holy war against the ‘infidels.’ I had to send a telegram to contradict this misrepresentation of our Movement.

“We have started a monthly paper from here in Malaya, the vernacular of the people, and we are thinking of making it a weekly if it proves a success. The Ulema are issuing fatwa after fatwa against us, and people abuse me openly. Some of the nobles are favourably disposed towards us, and they are beginning to defend our movement against the Maulvis.”18

Press coverage

The activities of the Ahmadiyya Mission in Indonesia caught the attention of the local press. A glimpse is presented below:

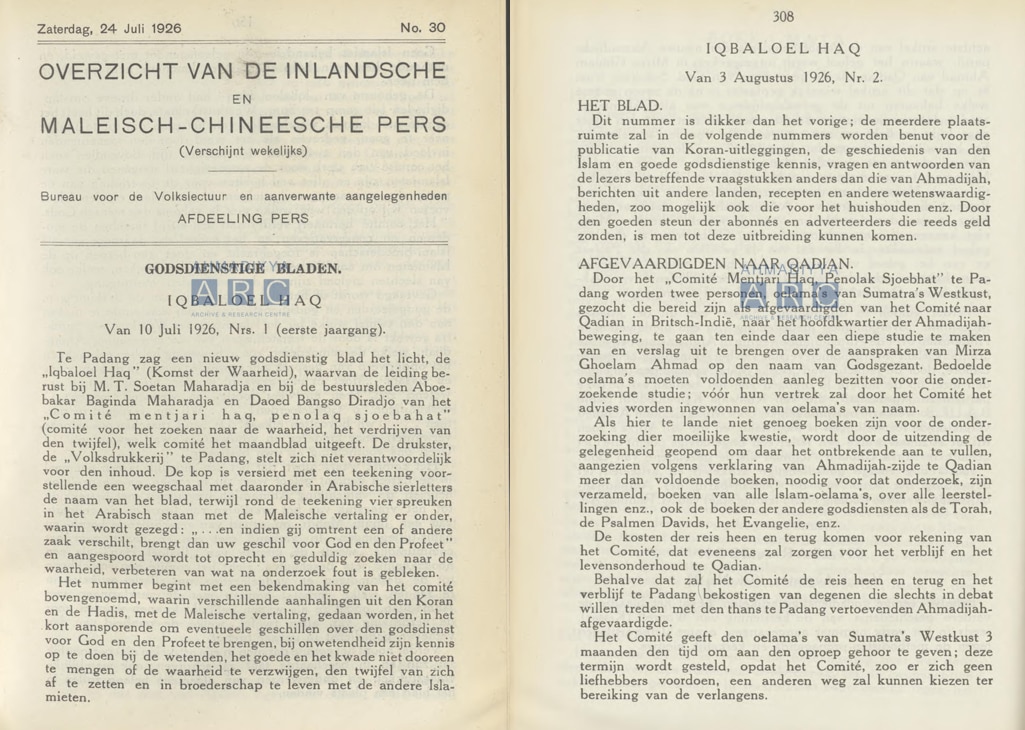

A Dutch periodical wrote about the above-mentioned committee and the launch of the magazine, stating:

“In Padang, a new religious magazine saw the light of day, the ‘Iqbaloel Haq’ (Acceptance of the Truth), headed by M. T. Soetan Maharadja and by the board members Aboebakar Baginda Maharadja and Daoed Bangso Diradjo of the ‘Comité mentjari haq, penolaq sjoebahat’ (Committee for the search of the truth, the dispelling of doubt).”19

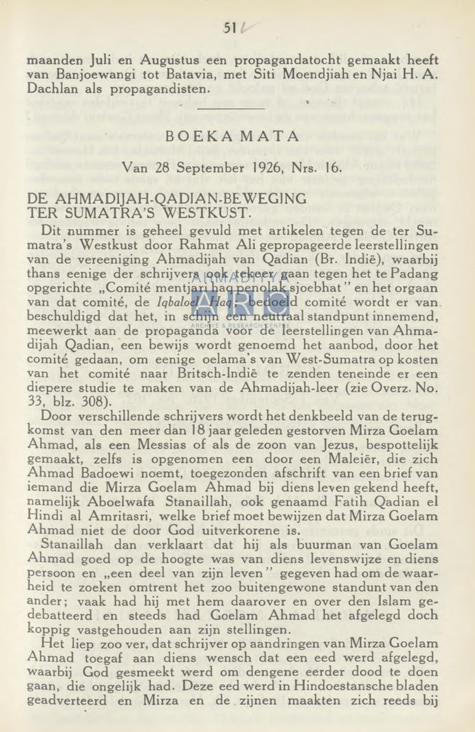

Another issue of the same periodical published an article, titled “The Ahmadiyya-Qadian Movement on Sumatra’s West Coast”, and mentioned the preaching activities of Hazrat Maulvi Rahmat Alira.20

This was followed by another article21 which mentioned another local periodical, Boeka Mata of 26 November 1926. The latter was devoted to the arguments against the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat and a letter to the editor from some Aboezeed bin Hilal was also mentioned in which he asked the editor for some details about the Ahmadi missionary and some local Ahmadis.

Another local journal, Mededeelingen: Tijdschrift voor zendingswetenschap – in its 1926 issue – wrote that a British-Indian Ahmadiyya missionary, Rahmat Ali, is travelling through Sumatra and propagating his beliefs. It also mentioned the magazine Iqbaloel Haq.

An announcement was made about a debate that was scheduled to be held on 9 January 1927 between Maulvi Rahmat Ali Sahibra and some Pakih Hasim.22

A detailed account was published about the missionary activities of Maulvi Rahmat Ali Sahibra which also mentioned the committee called “Mentjari Hak Penoelak Sjoebahat”.23

Another local newspaper published an article about his missionary activities. The article began with the introduction of the Promised Messiahas and his claims. It was stated that during the past two years, the missionary had succeeded in converting many locals to Islam Ahmadiyyat, for instance in Padang, Pandang, Fort de Kock, Fort van der Capellen and some other places. It was mentioned that the message is being spread through a magazine, titled Iqbaloel Haq. This was followed by some details of the debates with the non-Ahmadi Muslims of the local area.24

The same article was published by De Nieuwe Vorstenlanden on 3 December 1927.

The local newspapers announced about an upcoming gathering where a debate was scheduled to be held between the Ahmadiyya missionary and the non-Ahmadi clerics. However, the opponent did not come for the debate, hence, Rahmat Ali Sahibra delivered a speech about the prophecies mentioned in various scriptures in regards to the advent of the Promised Messiah.25

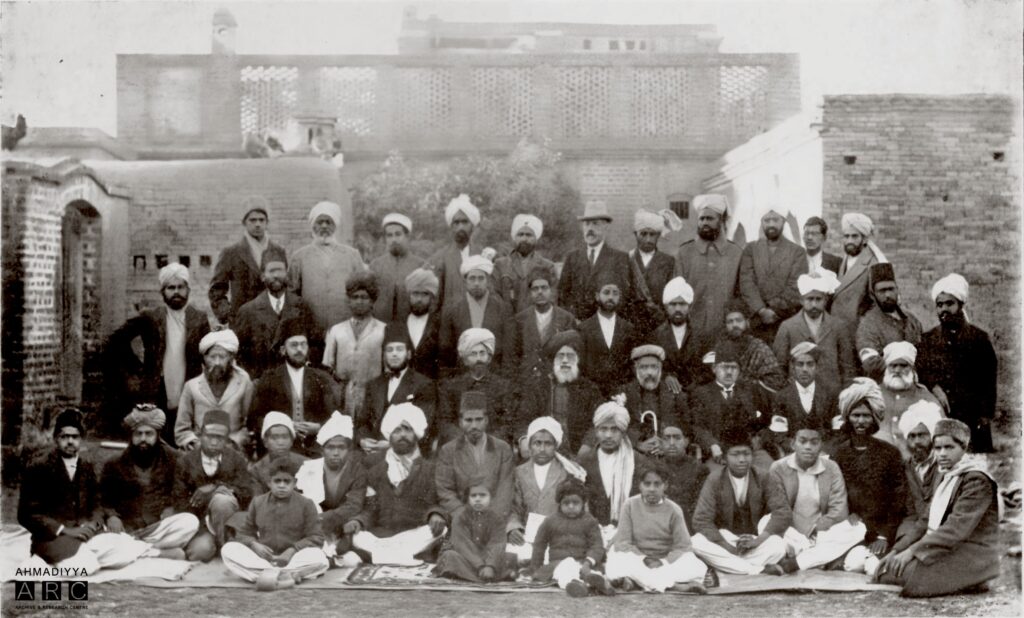

Another article emerged, featuring a group photo of the speakers who delivered speeches in 24 different languages at a historic Jalsa in Qadian on 29 January 1926.26

The speech in Dutch was delivered by an Indonesian, Ahmad Sarido Sahib27, who was studying in Qadian at the time. The article stated that in one of their previous issues they had mistakenly written that Hazrat Mufti Muhammad Sadiqra was the head of the Ahmadiyya Community. So, correcting its statement, the periodical wrote:

“Dr. M. M. Sadik, a leader of Ahmadiyya and a great scholar, said, ‘The head of the Ahmadiyya Community is Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad[ra] who is currently in Qadian.’”

The article continued by mentioning Hazrat Musleh-e-Maud’sra visit to England, and stated that he laid the foundation of the Fazl Mosque in London which was later inaugurated in 1926. The article further mentioned Hazrat Maulvi Abdur Rahim Dardra and Hazrat Malik Ghulam Faridra, and the missionary activities in London.

A lengthy article was published in a local newspaper about a local Ahmadi who had studied in Qadian for three years. This article narrated his experience in Qadian during those three years.28

According to a local newspaper, Maulvi Rahmat Ali Sahibra was supposed to go back to Qadian, however, this plan was postponed since no replacement had arrived yet.29

Eventually, in October 1929, Hazrat Maulvi Rahmat Alira returned to Qadian. It was reported by an Indonesian newspaper that he would soon return to Indonesia and that another missionary, Maulvi Muhammad Sadiq Sahib, would also come with him.30

These two missionaries reached Indonesia in December 1930, and hence began the second phase of the Ahmadiyya Mission in Indonesia. Their activities continued to attract the attention of the local press which served as a great means for spreading the message of the Promised Messiahas. For instance, a local newspaper published the photograph of the Promised Messiahas and gave an extensive introduction of his claims.31

The message continues to echo in Indonesia

The above was just a glimpse into the press coverage received by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat in Indonesia in the early years. The message of Islam Ahmadiyyat continued to echo in that country during the coming years as well, under the blessed guidance of Khilafat-e-Ahmadiyya.

Indonesian Ahmadis also played a huge role in the country’s independence from the Dutch and rendered great services for their homeland despite facing severe persecution. More details have been narrated in our previous article, titled “Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya’s role in Indonesia’s independence from the Dutch”.32

During this blessed era of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Vaa, Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya Indonesia is making even greater progress, and it will continue to flourish, insha-Allah.

Endnotes

1. Al Fazl, 4 December 1924, p. 2

2. Al Fazl, 20 August 1925, p. 1

3. National Archives of India, Foreign and Political Department, External (Secret), 1925, File No. 421-X

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Minhaj-ut-Talibeen, Anwar-ul-Ulum, Vol. 9, p. 169

16. Report Majlis-e-Mushawarat 1927, pp. 35-36

17. Anwar-ul-Ulum, Vol. 9, p. 412

18. The Review of Religions, September 1926, p. 1

19. Overzicht van de Inlandsche en Maleisisch-Chineesche pers, 24 July 1926

20. Ibid., 9 October 1926

21. Ibid., 4 December 1926

22. Bintang Timoer, 5 January 1927

23. Tjaja-Soematra, 17 November 1927

24. De Sumatra Post, 1 December 1927

25. Sumatra-Bode, 27 December 1927

26. Pertja-Timoer, 10 March 1928

27. Al Fazl, 2 February 1926

28. Tjaja-Soematra, 8 June 1928

29. Tjaja-Soematra, 23 August 1928

30. Sinar Deli, 16 May 1930

31. Pemandangan, 4 October 1933

32. Al Hakam, 24 December 2021