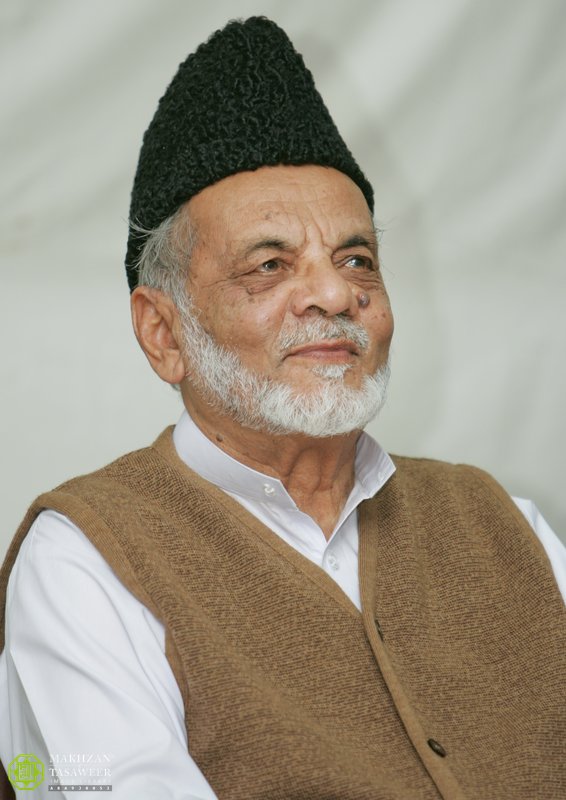

Asif M Basit, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre

To write about a personality as grand as Mir Mahmood Ahmad Nasir Sahib is truly a case of a small mouth attempting grand utterance. Had this beloved and respected elder been alive today, he would have sternly stopped me from writing this piece about him; just as he would try and stop me from many things.

For instance, whenever I requested him to grace a programme for MTA, the words would barely leave my lips when, in his distinctive manner – laced with the sweetness of affection and the flavour of elderly kindness – he would immediately say, “No, no. I won’t come. Invite someone else. Do whatever you wish. I won’t participate in your programme.”

Then I would seek permission from Hazrat Sahib and inform him that Hazrat Sahib had graciously permitted him to attend the programme. At this, he would never argue further. He would gently scold me while interjecting questions: “Where is the programme? When is it? What is the duration?” And what kind of scolding was it, really? Merely saying, “You have left me no room to refuse now!”

It wasn’t just about MTA programmes. It was about any word uttered from the lips of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih. No sooner would Mir Sahib learn of it than he would begin implementing it with full vigour.

But these aspects of Mir Sahib’s personality I observed much later. I had become acquainted with him during my youth; yet even that acquaintance began with a refusal from Mir Sahib. It so happened that after completing my secondary school in Karachi, I enrolled in a college there, but then had to relocate to Rabwah. My cousin, Muzaffar Chaudhry Sahib, was studying at Jamia at that time. As I began to socialise with him and his Jamia friends, I found the atmosphere of Jamia quite appealing and developed a desire to enrol there.

I presented myself before Mir Sahib, who was then the principal, and expressed my wish. He informed me that admissions had closed and there was no possibility of enrolment. Therefore, admission was not possible. He also advised that I should complete two years in college, earn my FA, and then come, though he added that few who came this way tended to persist. “Yes, I have two or three students who came from college but did very well and succeeded in Jamia,” he said. Here he mentioned Ataul Mujeeb Rashed Sahib, Raja Munir Ahmad Khan Sahib, and Fareed Ahmad Naveed Sahib. Fareed Sahib, who is now the principal of Jamia Ghana, was then studying in the fourth year and was also the zaeem of Nasir Hostel. Raja Munir Sahib when on to become the Sadr of Khuddam-ul-Ahmadiyya and later the principal of the junior section of Jamia Ahmadiyya Rabwah. And Ataul Mujeeb Rashed Sahib needs no introduction.

I continued visiting Jamia. In fact, my visits increased and I made new friends. When I got the opportunity to serve with Tashheez-ul-Azhan, I would frequently visit Fuzail Ayaz Sahib, the then editor, who resided in a quarter within the Jamia premises. Thus, mornings were spent at college. Upon leaving college (bunking, rather), I would go to Khilafat Library. From there, in the scorching afternoon of Rabwah, I would head home, and as soon as noon turned into afternoon, I would be in the premises of Jamia Ahmadiyya.

I would often encounter Mir Sahib at Jamia who always treated me with great affection. I never felt offended by his refusal to enrol me at Jamia because the reason he gave was entirely justified. On the contrary, I had taken a great liking to Mir Sahib, and with time, I continued to admire him even more. On occasions when I would meet him, or if he passed by on his bicycle, he would invariably share some affectionate remark accompanied by his gentle laughter: “Who have you come to have tea with today?” “Your friend was just leaving!”

On cold winter mornings, Mir Sahib would sit in the sun in front of the beautiful Jamia building, wearing a warm coat, warm cap, and gloves, reading something. I would stop my bicycle in front of his desk, dismount, greet him, ask for prayers, and after hearing one or two affectionate phrases or prayers from him, I would go and sit at the Jamia canteen. He never stopped me. I was perhaps the only outsider who roamed freely in Jamia (or rather, strutted about). And not only did Mir Sahib never stop or rebuke me, but I myself never tried to keep my visits to Jamia discrete. I would always meet him and offer my greetings. He would treat me with great affection. Perhaps he had in mind his refusal and the sentiments of a young man. Also that how this young man, instead of taking offense at the refusal, continued to maintain and strengthen the relationship. But the young man wasn’t doing any favour. He was captivated by the charm of Mir Sahib’s personality and satisfied his heart by meeting him for his own sake.

My visits to Jamia continued in this manner and so did Mir Sahib’s love and kindness. Over the course of two years, I completed my college education. But throughout all this, much water had flowed under the bridge and my priorities had somewhat changed.

I never went back to Mir Sahib for admission, nor did Mir Sahib ever ask, however, Mir Sahib allowed this relationship of affection to be maintained. And by relationship, I mean those brief roadside encounters where he would pause to give attention to a wayward young man, bestowing upon him the grace of his kindness.

Then came the days of Punjab University, and Lahore entangled me in its web. I would reach Rabwah on Saturday nights for the weekly holiday, spend Sunday partly resting and partly wandering about, and depart for Lahore early Monday morning. I would visit Jamia occasionally, and even in those occasional visits, I would sometimes have the honour of a brief meeting with Mir Sahib in the same manner.

He would inquire about my education and my wellbeing. I would request prayers, to which Mir Sahib would always raise his index finger in any direction and say that I should write “there” for prayers. While waving his finger, Mir Sahib wouldn’t calculate east or west. But everyone knew that the needle of the compass in Mir Sahib’s heart always pointed towards the court of Khilafat.

Then I moved to England, and the series of meetings with Mir Sahib was suspended. Two years later, I had the blessing of pledging to devote my life (Waqf-e-Zindagi) and was assigned duty at MTA. The Annual Jalsa was approaching when I received instructions from Hazrat Sahib to present myself for mulaqat. When I presented myself, I was instructed that the elders coming from Rabwah for this Jalsa were not only familiar with the Jalsa’s history but had been part of the Jalsa management for many years and were acquainted with every component of the Jalsa machinery: Chaudhry Hameedullah Sahib, Mirza Khurshid Ahmad Sahib, Sahibzada Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Sahib, and Mir Mahmood Ahmad Nasir Sahib. As I write these names, the disheartening realisation dawns that all have departed from this world. The last name departed a few days ago. Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raji‘un.

I informed all these elders. All agreed. Mir Sahib clearly refused, saying, “Ask the others; they know everything. What do I have to tell? They know it all.”

I simply said, “Mir Sahib! Hazrat Sahib himself has mentioned your name.” Silence fell for a moment and then came the words: “Oh? If Hazrat Sahib has said so, then tell me where the studio is in the Jalsa Gah. When should I arrive? How long will the programme last?” and so on.

This was the first programme where I had the honour of sitting with Mir Sahib and asking him questions. This humble man, free from any desire for pomp or vanity, did not even wait for the closing of the programme. I was still saying the concluding remarks to the viewers when Mir Sahib removed his microphone and, unknowingly, passed in front of the live camera and departed. The duty assigned to him by Hazrat Khalifatul Masih had been fulfilled and after this, he did not remain seated before the camera, and left the studio.

During this Jalsa and in the days that followed, wherever Mir Sahib met me, he would tell his admirers walking with him, “He ties me up and takes me to programmes.” Then in the many years that followed, whenever I invited him to a programme and told him that Hazrat Sahib had granted approval, he would laugh and repeat that I had learned how to tie him up and take him.

Mir Sahib would always inquire about the details of the programme. For many years, he stayed in a suite attached to a guest house across from Fazl Mosque. I had the opportunity to go there multiple times to explain the details of programmes. Next to Mir Sahib’s bed was a reading desk, a chair, and a reading lamp. And on the desk, Mir Sahib’s books were neatly arranged.

Upon receiving permission, I would enter, and Mir Sahib would be reading or writing something in the lamplight. Sometimes he would share what he had been reading. And what variety there was in his subjects of interest! Primarily known as an expert on Christianity and the Bible, Mir Sahib never missed an opportunity for the acquisition of knowledge in any discipline. The Quran, Hadith and writings of the Promised Messiahas were like his universe; but alongside these, from science to current affairs, and from global politics to environmental studies – no subject remained outside his sphere of interest. Yet never once did he flaunt his scholarship. If someone like me sought guidance on any topic, he would offer it with downcast eyes and a shy, hesitant voice, with the pure intention of providing direction. These were the cracks through which those present in Mir Sahib’s company could glimpse his profound scholarship. Otherwise, Mir Sahib himself never felt that he had drunk his fill from the ocean of knowledge and could now quench the thirst of others. Whatever he hesitantly offered was intended as guidance, and never as self-display.

Mir Sahib’s writings are numerous and if collected and published, they would form several volumes. His articles were of solid scholarly nature, distilling his deep research. It was my good fortune that occasionally I would receive an instruction from Mir Sahib that a certain reference was needed, or that a reference from a particular author’s work published by a certain publisher was meant to go in his article, and that I should obtain permission from the publisher.

The first time this happened, looking at the nature of the reference and the word count, I respectfully said, “Mir Sahib, permission isn’t required for this as it falls under fair use, and citing the source would suffice.” He replied, “Very well, please convey this to me through the publisher. I don’t want to cause any difficulties for the Jamaat’s publications.”

To satisfy Mir Sahib, I spoke with the publisher by telephone and informed Mir Sahib, but he remained unconvinced. I realised that his satisfaction would not be attained in any form short of written permission from the publisher; and it wasn’t attained until the written approval was procured and sent to Mir Sahib.

The next time I received a similar request from Mir Sahib, drawing on the previous experience, I submitted that the same principle applied to this reference as it had the last time. But for Mir Sahib, even the thought of Jamaat’s newspapers and magazines – already under restrictions and prohibitions – facing additional difficulties was unbearable. Thus, he had raised the threshold of precaution.

Mir Sahib’s research articles were free from the tint of confirmation bias; he presented facts, backed them with references, and where there was opportunity to express his personal beliefs, he took full care that they were contextually appropriate. Mir Sahib has departed, but his research articles will live forever and continue to guide those who walk the paths of research and writing – especially in avoiding bias, making timely expressions of personal opinion or belief, and in the subtleties of caution regarding citations.

Mir Sahib served as principal of Jamia Ahmadiyya Rabwah for many years. Students who graduated during his tenure, who were his direct pupils, meaning he taught them lessons himself, number in the hundreds and are serving around the world. Many of them are entrusted with key responsibilities.

During his stays in London, he would write a letter to Hazrat Sahib every day, personally take it to the Private Secretary’s office to present it. Hazrat Sahib’s Private Secretary, Munir Ahmad Javed Sahib, had also been Mir Sahib’s student. As much respect as Munir Sahib showed Mir Sahib, Mir Sahib approached him with equal respect, as though Munir Sahib had been his teacher. This was certainly Mir Sahib’s humility, but even more, it was respect for those who assisted in the work of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih, which kept Mir Sahib’s heart bowed with love.

After the programme “Rah-e-Huda” began, I met Mir Sahib outside Fazl Mosque during the next Jalsa season. He greeted me very warmly, extending his hand for a handshake – an honour he rarely, if reluctantly, bestowed on anyone. Then, as if sharing a secret but in a humourful tone, said: “See, it’s good I didn’t admit you. Who knows where you would have ended up. It was written in your destiny to come near Khalifa-e-waqt, dedicate yourself, and have the opportunity to serve.”

I recalled that day fifteen or sixteen years ago when I had presented myself to Mir Sahib seeking admission. I had left disappointed after being refused, but had never turned back to complain. Mir Sahib had left no room for complaint anyway. He always met me with great affection and even overlooked my frequent visits to Jamia, never making me feel an outsider. And if he remembered that refusal for sixteen years, then on that day I became convinced that Mir Sahib had held good wishes for my desire to dedicate my life. And what he used to say about prayer, gesturing eastward and westward with his hand, “Write there” – perhaps he himself had sometimes surely prayed for me.

When Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Vaa established the Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre and granted me the opportunity to serve in it, more avenues of contact with Mir Sahib opened. It was a new department with responsibilities around the Jamaat’s history. Hazrat Sahib, on multiple occasions, would say, “Ask Mir Sahib.” And I would ask Mir Sahib, and he would always provide guidance with great kindness. I always witnessed that Hazrat Sahib would view Mir Sahib’s opinion with great esteem and direct us to act according to his suggestion.

Much of the material related to the department’s responsibilities was scattered across various offices in Rabwah and hence, our department needed a full-time worker there. I submitted this to Hazrat Sahib, who instructed, “Tell Mir Sahib to suggest some names and then bring them to me.” I asked Mir Sahib, who suggested just one name; that only name was presented to Hazrat Sahib, and was graciously approved.

Eight years on, every day during these years, prayers for Mir Sahib have emerged from my heart, and insha-Allah, they always will. The person whose name Mir Sahib suggested proved to be a very diligent worker, quickly learning the work and implementing it meticulously.

What I learned from this was that although Hazrat Sahib had directed “suggest some names,” Mir Sahib found only one name suitable. Mir Sahib considered it a demand of honesty to suggest only what his heart testified was right – and nothing else just for the sake of it. Only that one name was presented to Khalifatul Masih, and the passage of time showed that what Mir Sahib had suggested was indeed appropriate. And after all, Allah always preserves the honour of Khalifa-e-waqt’s decisions.

Then another staff member from Rabwah was needed for a similar responsibility. This time, a very good understanding of English was an additional requirement. I submitted this to Hazrat Sahib, who again directed, “Ask Mir Sahib.” During those days, Mir Sahib had come to the UK for Jalsa. During the Jalsa days, I spotted Mir Sahib sitting in a car in Hadeeqatul Mahdi. As the moving car passed by, I raised my hand in greeting. Mir Sahib had the car stopped. Opening the door, he showed his kindness. I submitted that Hazrat Sahib had directed thus, and that I would also submit it in writing after the Jalsa. Mentioning the name he had previously suggested, he said, “For such tasks, there was only one name, which I already gave. And there are few now with English skills. But I’ll think and let you know.”

Along with this, he began to recall by name his former students skilled in English: “Mustansar Qamar is now in such-and-such department. So-and-so is here, so-and-so is there. Students don’t show keenness to learn English anymore.”

Our issue wasn’t immediately resolved then, but what gave me pleasure was that Mir Sahib hadn’t simply loaded his students with books and let them go. He was aware of everyone’s abilities and qualifications. He knew everyone’s talents and this memory hadn’t dimmed. He even knew that Hazrat Khalifatul Masih had instructed him to give suggestions, so what precautions needed to be kept in mind, and that one shouldn’t casually offer suggestions on the fly.

And speaking of Mir Sahib’s memory, I can’t help mentioning that Mir Sahib seemed to know the Jamaat’s history by heart. Not only did he know it but remembered those details that remain unrecorded in history books or are left out for various reasons.

One day I was walking with him towards the studio. Mir Sahib usually kept his gaze lowered. A young man passing by greeted Mir Sahib. After he had gone, Mir Sahib asked me, “Who was that?” I replied that his name was such-and-such. Then he asked, “Whose son is he?” Since the young man’s father had been residing in England for ages, I said, “You probably don’t know him, but his father’s name is such-and-such.” But I was astonishingly shocked when Mir Sahib laid out details of not only the young man’s father but even his grandfather in such depth that perhaps even the young man himself wouldn’t know. He shared many things about the family, and some things he suppressed under a sweet smile.

The incidents Mir Sahib related about this young man’s father were mostly from the time of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IV. And what aspect of his “Mian Tari” could Mir Sahib possibly not remember? Mir Sahib was among the true lovers of Khilafat. He had lived through the eras of four Khalifas and remained intoxicated with love for all four. He was of the same age as Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IVrh, they had spent their childhood and gone through the stages of youth together, stayed together in London for education, and had a relationship with him that was informal before his Khilafat. And this “Mian Tari” that occasionally slipped from his tongue in private gatherings wasn’t a lack of respect but was due to that love which, transcending the boundaries of respect, had touched the heights of devotion.

Memories of those times would flock like clouds, and Mir Sahib would keep relating them, smiling with joy. I took him in my car from Fazl Mosque, and as we turned the corner of the street onto the A3 road, Mir Sahib told me that he and Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IVrh, had travelled much on this road. Every weekend, he would come from his flat to the mosque, and we would travel in his small car (or in Mir Sahib’s words, motor) here and there, often taking this road. Then, with sorrow written across his face, he related that when Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IV’srh funeral was being taken along this same road to Islamabad for burial, and these scenes were being shown on MTA, he was strongly reminded of those times when the two of them used to travel together on this road. “It should be named Mirza Tahir Ahmad Road,” he said, letting his smile return to his face.

He remembered with great affection his time as a student in London with Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IVrh. He remembered the names of his teachers too. Mentioning one teacher, he told that they had given him a gift of the Holy Quran, which he had received with great love and respect. He had later moved to Canada. “I don’t know if he’s still alive,” he said.

The words “I don’t know” sounded unfamiliar coming from Mir Sahib. When I took leave of his company, I left with the burden of this “I don’t know” on my heart. Mir Sahib had mentioned the teacher’s name, so much of my night was spent searching for every resident of that name in Canadian directories. It came in handy that Mir Sahib had awakened this yearning in my heart on a London evening, so that all of the night here was daytime in Canada. I called every person bearing that name, and finally found one who had been the teacher. By then, Mir Sahib must have been about 80 years old, so you can imagine what stage of life the teacher would be in.

When I mentioned the motive of my call, he couldn’t recognise either name. When I mentioned the gift of the Holy Quran, both came back to him immediately, and also that one of them had later become the head of his community. I informed him of the death of that distinguished head, and also mentioned to the other student that he was well and remembered him. That teacher also drifted into the flourishing memories of those lush green days – paths which Mir Sahib often walked upon and took others along. And thanks to that teacher-student relationship, I, who am a user of the School of Oriental and African Studies Library, became even more enamored with it.

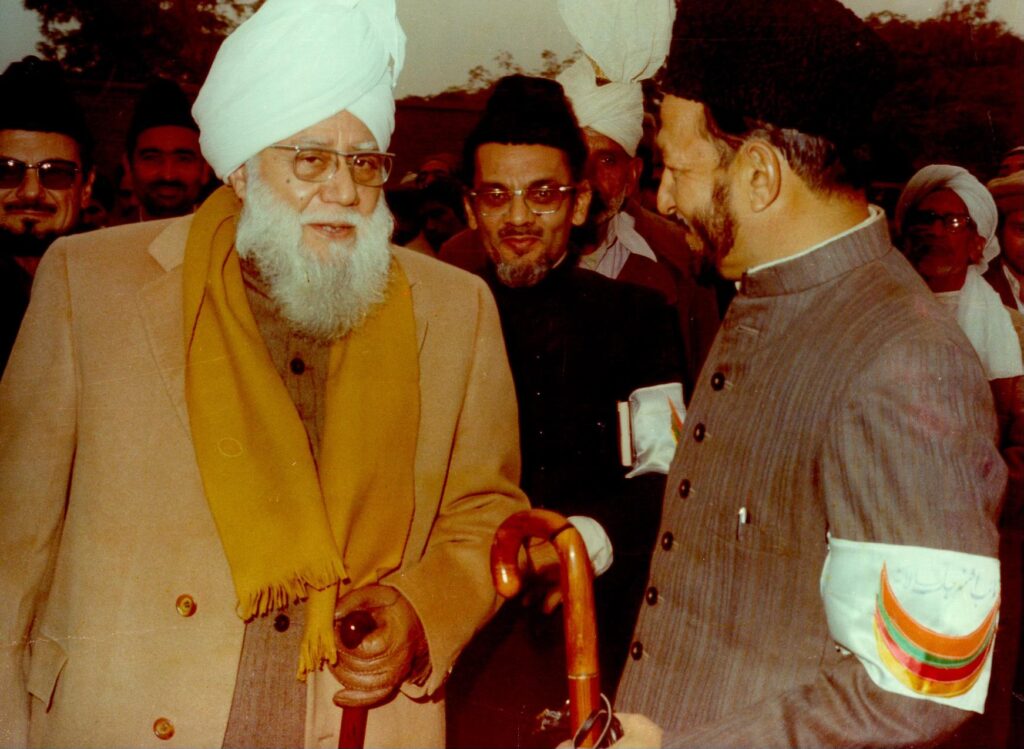

Speaking of Mir Sahib’s love for Khilafat, the relationship that Mir Sahib held with Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra was unparalleled. Also having the honour of being his son-in-law, Mir Sahib recounted that the match with his daughter, Amatul Matin Sahiba, was arranged in London. This was when Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra had come to London for treatment in 1955 and was residing at 63 Melrose Road, adjacent to the Fazl Mosque.

Mir Sahib narrated these memories with a gentle smile, reliving those beautiful moments. He reminisced how someone had told him that Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra had summoned him. Having sought permission, he entered the room where Huzoorra was staying. Huzoorra was facing the window and looking out of it, and continued to do so. At that moment, a proposal was made and he accepted the proposal immediately.

Mir Sahib was very cautious in his choice of words when speaking of the Khulafa, and he was particularly adept at this careful selection of words. Perhaps the words “accepted the proposal” had slipped from his tongue unintentionally. He then added that who even was I to accept or not; he said that everything he had was given by Huzoor, and what greater blessing could there be than that?

Whenever I asked him about Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra, he would always begin by saying, “How can I even start to tell? It cannot be narrated. Whoever has not seen Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra, cannot even imagine the extent of his astonishingly lovable persona […]” He would start with this phrase and then be very kind to his audience and quench their thirst of the inquirer.

I have always had a special interest in Hazrat Musleh-e-Maud’sra European tour of 1924. Wherever he went, wherever he stayed, and wherever he delivered speeches, I was fortunate by Allah’s grace to identify those locations. When all this was done, I sat and waited for Jalsa, meaning I waited for Mir Sahib to come to London.

The days of Jalsa arrived, and so did Mir Sahib. After the busy days of the Jalsa, I requested him to visit those places with me. Mir Sahib’s joy was overwhelming. At each site, we would pause, and speak about the significance of that place in relation to the 1924 tour. We recorded these moments because the very next day, these recordings were to be played in a programme of MTA.

We visited all the sites, and finally reached the place where the remarkable speech of that tour had been delivered at the conference of religions. Many years ago, I had learnt from Mir Sahib that what is known in the Jamaat as the Wembley Conference actually took place not in Wembley but at the Imperial Institute.

When we reached the site where the Imperial Institute no longer exists and has been replaced with the renowned namesake college and a museum. We were just beginning to envision and visualise that great conference and the revered Musleh-e-Maud when my colleague called to inform me that a fire had broken out in the Bait-ul-Futuh.

Upon informing Mir Sahib, he immediately returned from memory lane and urged me to return to Bait-ul-Futuh as soon as possible. For the entire journey back, he was visibly concerned and kept praying that no damage happens.

The very next day, our programme was scheduled to be recorded with the same footage, in the studio of Bait-ul-Futuh. However, due to the fire, at the behest of Hazrat Sahib, preparations were swiftly made to record all programmes in the Fazl Mosque studios of MTA.

That programme was recorded there the day after the fire, and I had the privilege of sitting beside Mir Sahib and benefitting from his knowledge – an opportunity also enjoyed by millions of viewers through MTA.

I mentioned earlier that Mir Sahib was intoxicated with love for all the Khulafa, often speaking fondly of Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra and also of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IVrh. Yet I feel it is my duty to declare, as I observed, that Mir Sahib did not remain confined to any one Khalifa’s era. He was immersed in this flowing spring – this river of the Khilafat-e-Ahmadiyya – and drank wholesomely from its clear waters. My testimony might be insignificant but countless others will also testify this observation and share more details. I simply state that I have seen Mir Sahib so immersed in love for Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Vaa, that those like myself, who claim the love for Khilafat, are simply put to shame.

Once I asked, “You must remember the childhood days of Huzoor.” He replied, “What childhood? When Huzoor turned forty and joined Ansarullah, one day we happened to walk together toward Masjid Mubarak for prayers. I said, ‘It seems like you were born just yesterday, and today you’ve joined Ansarullah?’”

Through his actions, we learned from Mir Sahib that the relationship with Khalifa-e-waqt transcends the worldly standards of time and space. The Khalifa is God’s chosen one, God’s beloved. Before him, age, experience, knowledge – all bow down at his feet.

Despite him being many years older than Hazrat Sahib, whenever Mir Sahib was in the company of Hazrat Sahib, he stood like a simple child, melting in devotion. And if Hazrat Sahib sat down, I saw Mir Sahib sitting at Hazrat Sahib’s feet. On many occasions, I observed that when a group photo was about to be taken, Mir Sahib would rush to sit at Hazrat Sahib’s feet. This was an expression of his belief that no matter what a person becomes in life, their true place is at the feet of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih. This was not only an expression of Mir Sahib’s faith and conviction but also a profound lesson for us.

I continued to have the opportunity of receiving spiritual nourishment from Mir Sahib during the days of Jalsa Salana UK. Then Mir Sahib’s health was not what it once was. I consider it necessary to share another matter, and obviously Mir Sahib didn’t tell me this himself.

One day, due to poor health, Mir Sahib couldn’t cross the road to offer Maghrib and Isha prayers behind Hazrat Sahib in Masjid Fazl. The next day, he submitted a written apology: “Huzoor, despite living so close, I couldn’t attend prayers at the mosque yesterday.” What he wrote further need not be disclosed as those were the heartfelt words of a devout lover of Khilafat.

Then came the infamous coronavirus, and, unfortunately, Mir Sahib’s visits for Jalsa came to an end. May Allah bless Dr Ghulam Ahmad Farrukh Sahib who, at my request, would arrange phone calls with Mir Sahib. The day after Hazrat Sahib mentioned the late Chaudhry Hameedullah Sahib upon his death, I spoke with Mir Sahib on the phone. It’s difficult to put into words the emotions with which Mir Sahib concluded our conversation that day. He said, “Tell Hazrat Sahib that whatever he said about Chaudhry Sahib, I am an eyewitness to all those things. All that Hazrat Sahib has said is exactly as it happened. I was there when Chaudhry Sahib became Sadr Khuddam-ul-Ahmadiyya. When Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIIrh expressed affectionate words about him, I saw it all with my own eyes and heard it with my own ears. Tell Huzoor that I don’t have the strength to write these days, otherwise I would have written it myself.”

There were some other words he asked me to convey to Hazrat Sahib, but they were his trust to be delivered to Hazrat Sahib alone. So I cannot betray that trust and cause distress to Mir Sahib. But those words made my heart sink. For thirty years I had heard Mir Sahib saying, “My time is now near.” But that day, although he didn’t use those exact words, they echoed in a very painful way.

My last meeting with Mir Sahib was during the Jalsa Salana days of 2019. This was the last Jalsa before the Coronavirus pandemic spread. It had only been a few months since Hazrat Sahib and the headquarters had moved to Islamabad. Islamabad was in full bloom in the English summer, and Mir Sahib was witnessing this beauty for the first time; and also for the last time.

Mir Sahib was sitting in a wheelchair, and his son Syed Muhammad Ahmad Sahib was taking him toward his residence. I stepped forward to greet him and requested Muhammad Ahmad Sahib to let me push the wheelchair. He asked Mir Sahib, who, as always, refused. And as always, compelled by my innocent insistence, he finally granted permission.

When the wheelchair reached in front of Mir Sahib’s residence, and I could go no further, I asked for permission to leave. Here Mir Sahib said something that proved to be his final words to me in person. He said, “You were so insistent on pushing the wheelchair. Make sure you come to shoulder my coffin!”

My most respected Mir Sahib! The morning you departed this world, you were buried that same evening after Asr prayers. In such a short time, what flight could have taken me to you to obey your command? I am sorry!