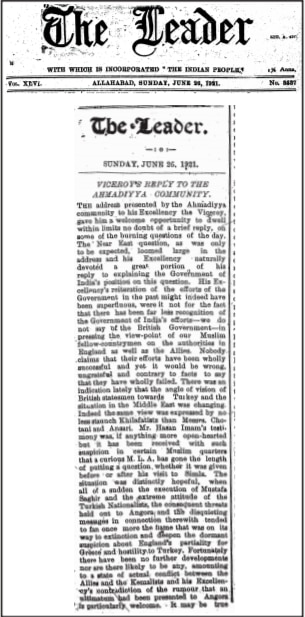

The Review of Religions (English), June 1921

Before we present the speech of Lord Reading, the then viceroy of India, a glimpse of this event mentioned in the 27 June 1921 issue of Al Fazl is as follows:

“The delegation reached the Viceregal Lodge, Shimla, on 23 June 1921 at 11 am to welcome the Viceroy of India, Lord Reading, on behalf of the Ahmadiyya Jamaat.

“The delegation comprised of 30 members who had come from different provinces of India in their distinctive local dresses. Four uniformed military officers who were also wearing their medals were part [of the delegation].

“This entire party left the rest house in rickshaws for the Viceregal Lodge. The line of rickshaws was about a furlong [660 feet] long. This view had a special effect on the people of the city. Consequently, it also became a means of tabligh because everyone who saw that sight enquired about the people and asked as to what has happened.

“The viceroy’s aide-de-camp was present for the reception at the door. When all the members of the delegation were seated in their respective places, the viceroy came. His private secretary first introduced Chaudhry Zafrulla Khan, Barrister Lahore, Secretary to the Delegation, and then Chaudhry Sahib introduced the members of the delegation one by one. The Viceroy shook hands with everyone and went to his chair.

“After this, Chaudhry Zafrulla Khan Sahib read out the address in which the viceroy was welcomed by the Ahmadiyya Jamaat and the family of the Promised Messiahas, and his teachings were mentioned. The Jamaat’s services for peace were also presented briefly. Then there was a mention of the current state of affairs and unrest in India and in this regard, the attention of the government was drawn to certain issues.

“After the address, Hazrat Nawab Muhammad Ali Khan Sahib presented the address [to the viceroy] in a casket. The viceroy then responded to the address and spoke for about 25 minutes. Acknowledging the services rendered by the Ahmadiyya Jamaat and expressing his delight on behalf of the government, the Viceroy said, ‘I thank you for your statement that you are all to be depended upon in whatever emergency may occur.’ The Viceroy also gave detailed answers from his point of view on the issues that were brought to his notice, save for one matter which was not explicitly mentioned by him.

“At the end, he again thanked the Ahmadiyya Jamaat and members of the delegation, and concluded his speech […] On this occasion, the relevant literature of the Jamaat was also presented to the Viceroy through his private secretary.”

Below is the speech of the viceroy in response to the Ahmadiyya Jamaat’s welcome address (Editor, Al Hakam):

I am glad to have the opportunity today to meet you, the representatives of the Ahmadiyya community, and to thank you for the congratulations which you have been good enough through your secretary to express in the address to me upon my assumption of the office of Viceroy of India. I have listened with very deep interest to the account of the origin and growth of your community, and have heard with real satisfaction of the loyal services which your community has been able to render to the king-emperor. Let me say that I was impressed on the introduction of your members by finding so many representatives of different professions, and of different vocations of life, and in particular may I be permitted to say how pleased I was to find that among the members of this deputation today were two sons of the holy founder of your religion.

And again let me add that it was a special satisfaction to see amongst you so many who by their costume, by the uniform they wear, and the medals upon their breasts, are clearly ready to defend with their lives in the future, as they have done in the past, whenever the necessity may come, the loyalty that they owe to their king-emperor.

The services of your community, let me assure you, are not less appreciated by me than by my predecessor. I congratulate you heartily on the spirit of loyalty which you have displayed sometimes in the face of very great difficulties, as well as on the measure of assistance which you have been able to render.

Momentous problems

You have referred in moderate language to the momentous problems with which my government is confronted, and you have made certain suggestions with regard to them. You have particularly referred to certain difficulties with which the government is confronted in the near East, and upon those you have laid special stress. Reference is to be found also to other difficulties such as internal problems, and the conditions of the Indian, and a recognition of citizenship in the British Dominions and Colonies. You will appreciate that it is not possible within the limits appropriate to a reply to your address to traverse the whole ground covered by these difficult and complicated questions, and you have the advantage that though in making these representations to me you have the responsibility of expressing your views, it is upon government that the duty devolves of giving practical effect to them. But in general terms, I can assure you that all these questions receive the constant and anxious attention of government.

The Treaty of Severs

In particular, I would ask you to bear in mind the efforts that the government of India have consistently made to secure terms of peace with Turkey, more in accordance with the religious susceptibilities of our Moslem fellow-subjects in this country.

I speak from personal knowledge when I tell you that no reproach can justly be made by Indian Moslems against Lord Chelmsford or the present Secretary of State, for both of these distinguished gentlemen persistently and most forcibly represented the Indian Moslem views, and left no stone unturned to place them before the Allied Powers. If the facts were more fully known, a more generous acknowledgment would be made to both of these distinguished friends of India.

Since I have been Viceroy, I have done the utmost in my power to continue to represent these views to his Majesty’s government, and as you are well aware, this deputation has received the most sympathetic consideration. I do not mean by that that everything that they asked was promised to them. That was hardly possible, and indeed the Prime Minister explained that he could not fully accept those representations. But he went a very long way, as I am sure you will admit, when he made the promise, and when he used his powers, as he has used them, for the purpose of getting the Treaty of Sevres modified very much in favour of Turkey.

That these terms have not yet been accepted by the Powers involved cannot be laid to the fault of the Prime Minister or of the British Government. I wish that the facts to which I have just referred were a little more generally recognized. I know that many Mahomedans are free to admit that a great change has been made in the situation by the reception which the Prime Minister gave to the deputation, and by the statements that were made afterwards by Mr Montagu embodying the terms the British government was prepared to put forward to Greece and Turkey, and of which the British government is seeking its best to obtain acceptance. But it does seem as if there are some among the Indian Moslems who are more anxious to find fault with the British government and more desirous of embarrassing the British rule in India than they are of recognising the efforts that are made to placate, and indeed even to content, the Indian Moslems.

Baseless rumours

There is at the present moment a recrudescence of the tendency in some quarters to represent Great Britain as hostile to Islam, and to indulge in references to the attitude of his Majesty’s government towards the Kemalist government at Angora, which do not seem to be warranted by the facts. The rumour that an ultimatum has been presented to that government by the British is, so far as I am aware, untrue. I don’t know whence the rumour comes. I have heard nothing of it his Majesty’s ministers have on repeated occasions emphatically contradicted the suggestion that they are giving the Greeks any assistance in the campaign now proceeding in Asia Minor.

A great responsibility rests upon those who choose to make themselves the means of disseminating the notion in India that in its relations with the Angora government his Majesty’s government has only shown another example of its alleged hostility towards Islam, and of its resolves to crush the last remnant of Islamic temporal power. There is not a vestige of truth in that statement. Nothing could be further from the truth than to say that Britain is out to destroy the Islamic power, and let me tell you that no statement is more calculated to tend to trouble and unrest among Indian Mahomedans.

I most earnestly hope that as a result of events that are now proceeding, and of the efforts which are being made, as shown by the reports of Mr Winston Churchill’s speeches on behalf of his Majesty’s government, that their desire to bring about a reasonable peace with Turkey will succeed. I fervently trust that the neutrality so recently re-affirmed by his Majesty’s government in the struggle between Greece and Turkey may be continued, and that if the conflict in the near East must proceed, Britain may not be compelled to depart from her declared policy, and I trust also that a just and reasonable peace may result from the endeavours of the Allied Powers between Greece and Turkey, which will content the Moslems, and particularly the Indian Moslems, who constitute so great and important a portion of the population of his Majesty’s subjects.

Indians in the Dominions

I will not detain you by reference in detail to other matters. I have to say that I am naturally impressed with the difficulties which have arisen here in India as to the position of Indians in the Dominions and Colonies of the Empire. India’s cause has always found a stalwart champion in this respect in the government of India.

At this moment, India’s representatives are in London, and will sit at the Imperial Conference. Thus you may be assured that the views of the people of India will be ably represented to the representatives of the Dominions, and I need scarcely say that for my own part I shall always give this problem, closely affecting as it does position in the Empire, the very earnest attention that it most unquestionably merits. It has been my good fortune to meet round the conference table, or at the Imperial War Cabinet, all those who now represent his Majesty’s Dominions, they are statesmen who are never blind to the considerations of equity and I feel convinced that they will give every heed to the Indian representations, always remembering their own responsibilities to their own constituents and to their own country, and to me the very fact that they will meet and discuss the problem is a great gain. Such a meeting always gives me hope and confidence.

Internal problems

With regard to internal problems, let me only add that, as you are aware, I have given constant attention to them from the time that I landed in India, and assumed office. My most earnest wish and I know it is shared by every one of my colleagues, is to promote a calmer and healthier political atmosphere based on mutual understanding, mutual respect, mutual sympathy and on racial equality.

I am in full accord with you that wrongful acts must not be vindicated in a spirit of false pride, or to uphold an imaginary prestige, and I agree of course that justice must be meted out without fear or favour to all who offend, whether they be British or Indian. Our aim is by means of patience and tolerance, combined with firmness in the maintenance of order, and the protection of peaceful and law abiding citizens, to arrive at better relations between the rulers and the ruled.

British officers’ attitude towards Indians

One observation only I must make in reference to your address. You speak of British officers and you make some observations with regard to their attitude towards Indians. I am not sure what is meant. If you mean British officials, then I am sure that even though it may well be that errors are sometimes committed, they are not purposely made. There may be mistakes of judgment as will happen to us all, but there is no foundation, I verily believe, for any suggestion that the British official is anxious to assert racial superiority over the Indian with whom he comes in contact. I am not sure that the suggestion is made, but as the language might imply it, I could not pass it.

I have watched with the greatest care the reports which come to me from the various provinces of the actions of the officials. I know that here, as at Delhi we are at a great distance from a number of our officials, but from my own observation up to this moment and I am still naturally watching with care, I am deeply impressed by the high sense of duty and responsibility of these men, who are serving the king-emperor and India in their endeavours to govern in the districts to which they are appointed, and who manifest a great desire to act wisely and justly.

If you mean by British officers, those who hold the King’s Commission, then I again am rather at a loss to understand your observations. I am brought into close contact with those at the head of military affairs here, and who have particular charge of British officers in this country, and I have made it my business to enquire and am persistently enquiring, as to whether or not there is or is not any foundation for the suggestion of an assertion of racial superiority by British officers.

I am assured by those who share my views, and are in the best position to know there is none. I make these remarks lest there might be a misunderstanding in reference to the expression that fell from you, but do not think for a moment that we claim infallibility, either for ourselves at Simla [now Shimla] or for those who administer in remote districts. Far from it, we know how difficult the situation is, we know that human judgment is not infallible. All we can achieve is to act according to the dictates of our own honour, of our own conscience, with a supreme desire to do our duty, both to the king-emperor and to India.

India’s momentous voyage

In conclusion, I am very grateful to you for your cordial wishes and congratulations to Lady Reading, who daily finds greater satisfaction in her duties. For myself, I am encouraged by your support. India has embarked on her momentous voyage towards representative government and equal partnership in the Empire. With all my heart, I wish her success.

I am privileged in that I have been entrusted for a time by the king-emperor with the task of assisting in setting her course truly and guiding her safely on her great enterprise, but the captain on the bridge must have the cordial and ready assistance of all on board, officers, crew, and passengers, and I know gentlemen that I shall receive that assistance from you in whatever capacity you may be called upon to perform it. I thank you for your expressions of loyalty, I thank you for your statement that you are all to be depended upon in whatever emergency may occur.

(Transcribed by Al Hakam from the original article in The Review of Religions [English], June 1921)