Fazal Masood Malik & Farhan Khokhar, Canada

Nations sometimes have a way of forgetting their most interesting alliances. Among the overlooked collaborations that shaped the modern world, few are as compelling as the relationship between Muhammad Ali Jinnah and the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community during Pakistan’s struggle for independence. This partnership, meticulously documented in historical records, reveals how a faith community and political pragmatism can combine to achieve extraordinary results.

This collaboration also reflected a broader pattern – the pivotal role of Ahmadiyyat under the leadership of Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra in supporting Muslim nations and leaders during periods of colonial oppression across multiple independence movements. Beyond Pakistan, the influence of the Community extended to struggles in Kashmir, Algeria, Palestine and Indonesia, emphasising the importance of principled leadership, moral integrity, and collective support in liberation movements.

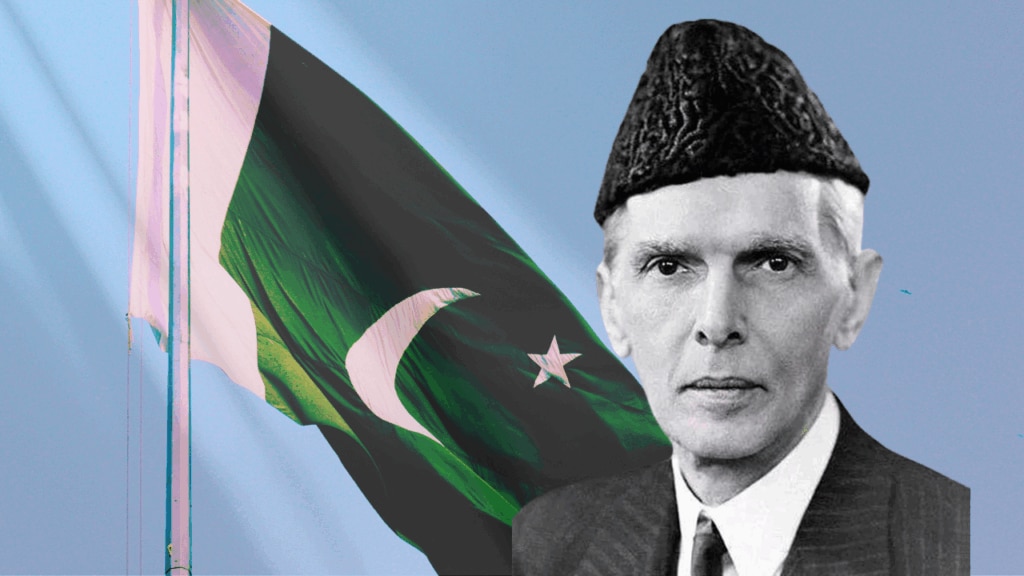

The making of a leader

Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s transformation from a Bombay barrister to Pakistan’s “Quaid-e-Azam” (meaning “great leader”) mirrors the broader Muslim awakening under British rule. Born in Karachi in 1876, he studied law in London during the 1890s, where exposure to figures like Lord Morley and Dadabhai Naoroji shaped his understanding of constitutional governance. (Jinnah, Creator of Pakistan by Hector Bolitho, p. 12)

Returning to practice law in Bombay, Quaid-e-Azam entered politics in 1908 through the Indian National Congress. His journey from Congress member to Imperial Legislative Councillor to Muslim League president by 1916 reflected his growing awareness of the particular challenges facing British India’s Muslims. (Jinnah of Pakistan by Stanley Wolpert, p. 33, 43)

Yet by 1929, frustrated with political discord and factional infighting, he abandoned politics altogether and settled in London. (Jinnah, Creator of Pakistan by Hector Bolitho, p. 80) This moment of despair would prove crucial. It was then that an unlikely saviour emerged; this saviour was none other than Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra.

A partnership takes shape

The partnership began in 1927 during a crucial meeting in Shimla. Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra, attending political discussions on religious freedom, encountered Quaid-e-Azam and quickly recognised his potential. Writing later, he described Jinnah as “a very clever, capable, and sincere servant of the nation” who cared more about national progress than personal advancement. (Anwar-ul-Ulum, Vol. 10, p. 45)

This assessment proved prescient. While most Muslim organisations (including the influential Deobandi scholars, Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind, Jamaat-e-Islami, and Majlis-e-Ahrar) opposed Jinnah’s secular approach, only the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community supported him consistently.

The relationship deepened through practical collaboration. When the Muslim League split over boycotting the Simon Commission in 1929, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra successfully mediated between the feuding factions, with Mufti Muhammad Sadiqra participating directly in reconciliation talks between Jinnah and his rival Muhammad Shafi. (Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyyat, Vol. 6, p. 103)

The partnership’s most dramatic moment came in 1933. Quaid-e-Azam, disillusioned after the Round Table Conference, abandoned Indian politics for his London law practice. Recognising the Muslims’ need for a political leadership, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra dispatched Abdul Rahim Dardra, the missionary in London at that time, with a crucial mission: to convince Muhammad Ali Jinnah to return and take charge of the perilous independence movement.

Their meeting lasted four hours. Abdul Rahim Dard Sahibra argued that abandoning Muslims at such a critical juncture “would be tantamount to betrayal of the nation.” The intervention worked. Shortly after, Jinnah appeared at Fazl Mosque in London for an Eid ceremony, beginning his speech with these memorable words: “The eloquent persuasion of the Imam left me no escape.” (Encyclopedia Quaid-e-Azam by Zahid Hussain Anjum, p. 780)

His address on “India’s Future” attracted widespread press attention, marking his return to active politics. The Sunday Times reported on the “large gathering” where “Mr Jinnah, the famous Indian Muslim spoke on India’s future.” (Sunday Times London, 9 April 1933)

Without this intervention, Pakistan’s history might have unfolded very differently, if at all. The alliance proved its worth during critical moments. In 1947, as Punjab’s future hung in balance, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra provided crucial advice about the Boundary Commission. His letter to Quaid-e-Azam outlined a negotiating strategy: “Indeed, you should insist on Sutlej, but at the same time say that if we are pushed beyond Beas, we will not accept it.” (Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyat, Vol. 9, p. 479)

More remarkably, the community helped orchestrate the Muslim League as the sole representative of Muslims by ensuring the resignation of Punjab’s Chief Minister Malik Khizar Hayat. This cleared the path for the Muslim League’s control of a crucial state. Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra wrote to Quaid-e-Azam: “Sir Muhammad [Zafrulla Khan] came there yesterday and discussed the matter with me. […] They have agreed to resign. […] Now you have a great lever to get Muslim rights from your opponents.” (Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah Papers, Vol. I, Part 1, pp. 164-165)

The personal dimension of their relationship emerges in an extraordinary episode during the 1945 elections. Quaid-e-Azam sent a message through Sardar Shaukat Hayat requesting prayers from Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra. When the message arrived at midnight in Qadian, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra “came down immediately” and assured the messenger, “Please convey to the Quaid-i-Azam that we have been praying for his Mission from the very beginning. […] No Ahmadi will stand against a Muslim Leaguer […].” (The Nation that Lost its Soul by Sardar Shoukat Hayat, p. 147)

A trusted “son”

The trust that Quaid-e-Azam placed in the Community manifested in his repeated appointments of an Ahmadi, Sir Muhammad Zafrulla Khanra, to key positions. Speaking in India’s Central Assembly in 1939, he declared: “I wish to record my sense of appreciation […] to the Honourable Sir Muhammad Zafarullah Khan, who is a Muslim and it may be said that I am flattering my own son.” (Speeches, Statements & Messages of the Quaid-e-Azam, Vol. II, p. 973)

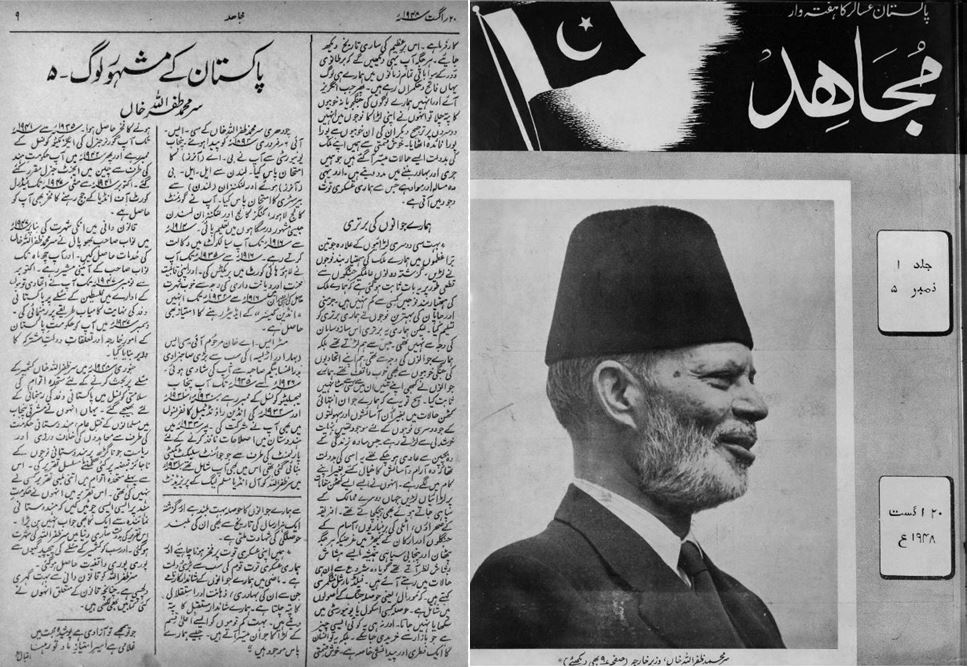

Zafrulla Khan’sra contributions were substantial. He drafted the Pakistan Resolution of 1940 – the foundational document demanding a separate Muslim state. (Facts are Facts: The Untold Story of India’s Partition by Wali Khan, p. 40) Quaid-e-Azam later appointed him to represent the Muslim League in the Punjab Boundary Commission, lead Pakistan’s first UN delegation, and serve as the new nation’s first Foreign Minister.

In 1947, he was specially nominated by Quaid-e-Azam to represent Pakistan in the United Nations, where he brilliantly advocated the case of Palestinian Muslims. (The Muslim, 2 September 1985) For a leader famously particular about trust and competence, this pattern of appointments spoke volumes.

Conclusion

On a matter of principle, Quaid-e-Azam supported the community. At the 1944 Muslim League session, when clerics sought to bar Ahmadi Muslims from membership, he intervened to defeat the resolution. (Nawa-i-Waqt, 10 October 1953)

During the crucial 1945 elections, Quaid-e-Azam released the community’s endorsement to the press, fully understanding the

value of its impact on public opinion. (Dawn Delhi, 8 October 1945)

While other Muslim groups opposed Quaid-e-Azam for theological or political reasons, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community supported him based on character assessment and shared commitment to the welfare of Muslims. Most importantly, the collaboration between Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra and Quaid-e-Azam is a reminder that liberation movements succeed through coalitions united by shared values rather than identical beliefs.

Ironically, a nation central to this collaboration is trying to erase this relationship from history. But as Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra wrote in his condolence message upon the death of Quad-e-Azam, “Great people always remain alive because of their achievements.” (Daily Al Fazl Lahore, 12 September 1948)