Iftekhar Ahmed, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre

In a mid-20th-century survey of Middle Eastern religions, a brief but significant assertion is made regarding the theology of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat.1 The author, AJ Arberry, a noted scholar of Islamic studies, remarks that the Promised Messiahas appeared not to accept the orthodox Muslim doctrine of the Quran’s eternal and uncreated nature, a conclusion purportedly based on a direct conversation with the then-serving imam of the London Mosque. This assertion, recorded in a reputable academic work, presents a clear puzzle, for it stands in stark and direct contrast to the voluminous textual record left by the Promised Messiahas and his immediate Successors.

This article will demonstrate that the foundational texts of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat, when examined in their own context and with attention to their specific theological terminology, articulate a consistent, multi-faceted and sophisticated position affirming that the Quran is, in fact, uncreated (ghayr makhluq).

The argument will proceed not by simple counter-assertion but by a systematic examination of the primary sources, beginning with the foundational metaphysical framework upon which the entire doctrine rests, moving to the explicit creedal statements from the Jamaat’s highest authorities, examining how the leadership framed the debate’s central question and historical context, exploring the supporting theological structure that identifies the Quran as a divine attribute, addressing the nuanced resolutions offered for apparent paradoxes regarding the mechanics of revelation and the status of the Word of God and concluding with an analysis of the remaining philosophical arguments that reinforce this core position.

The centrality of this inquiry to the Ahmadi theological tradition is explicitly established by Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIra, who identified the entire controversy as a necessary subject for any substantive study of the scripture. In a single, dense passage from his work Fada’il al-Quran, he defined the issue by its classical name, posed the pivotal research question at its heart and immediately tethered it to its most potent historical symbol: the suffering of Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal.

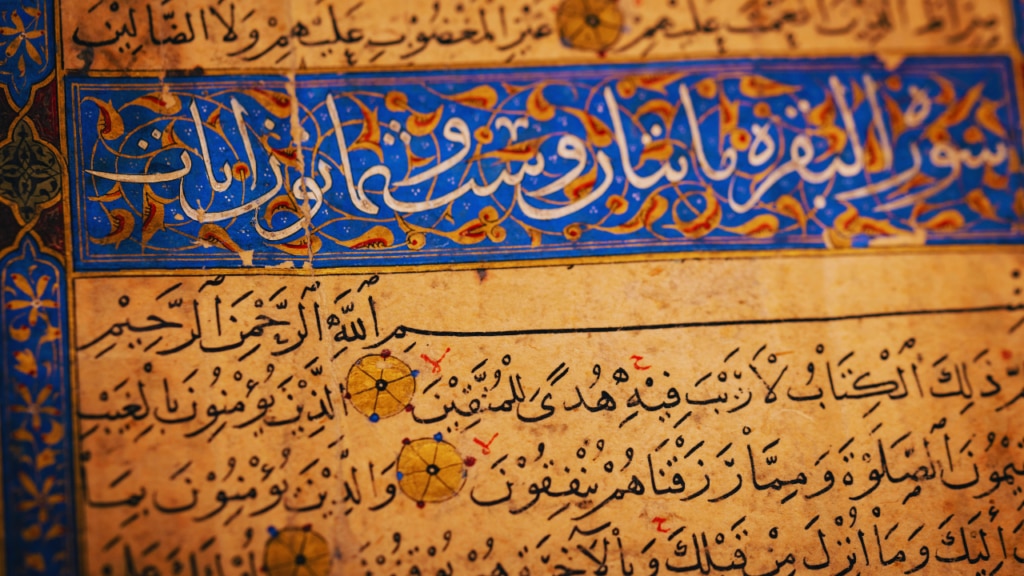

خلق قرآن کا مسئلہ

(۲۷) کلام الہی کو خدا تعالیٰ کے علم سے کیا نسبت ہے۔ پہلے زمانہ میں اس پر بہت بڑی بحث ہوئی ہے۔ اور بڑے بڑے علماء کو خلق قرآن کے مسئلہ پر ماریں پڑی ہیں۔ حضرت امام احمد بن حنبل کو عباسی خلیفہ نے مار مار کر اتنا چور کر دیا کہ وہ فوت ہو گئے۔ غرض خلق قرآن کے مسئلہ پر بھی بحث ضروری ہے یعنی خدا کے کلام کو خدا سے کیا نسبت ہے۔

“The issue of the createdness of the Quran

“(27) What is the relationship of God’s Speech to God’s Knowledge? In former times, a great debate took place on this and great scholars were beaten over the issue of the createdness of the Quran. An Abbasid Caliph had Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal beaten so severely that he passed away. In short, a discussion on the issue of the createdness of the Quran is also necessary – that is, what is the relationship of God’s Speech to God?”2

This statement, presented here at the outset, provides the internal justification for the present analysis and serves as a roadmap for the key themes – theological, philosophical and historical – that the Jamaat’s leadership considered essential to this debate.

The foundational distinction – amr vs. khalq

Any substantive examination of the Ahmadi position regarding the nature of the Quran must begin with a foundational theological principle articulated with marked consistency in the writings of the Promised Messiahas, a principle that serves as the primary hermeneutical key to the entire question – namely, the categorical distinction drawn between God’s creation (khalq Allah), a category encompassing all phenomena operating through intermediary causes, and God’s Command or Affair (amr Allah), a separate order of direct divine effectuation. This conceptual division is not a peripheral point, it is the principal framework through which the issue is consistently addressed, establishing two distinct metaphysical domains of divine action whose properties are mutually exclusive.

The Promised Messiahas deploys this core concept as a direct rebuttal to the naturalist proposition that divine revelation is merely an elevated form of human thought, identifying such thoughts as belonging to the created order:

اس کا جواب یہ ہے کہ یہ تمام خیالات خلق اللہ ہیں، امر اللہ نہیں اور اس جگہ خلق اور امر میں ایک لطیف فرق ہے۔ خلق تو خدا کے اس فعل سے مراد ہے کہ جب خدائے تعالیٰ عالم کی کسی چیز کو بتوسط اسباب پیدا کر کے بوجہ علت العلل ہونے کے اپنی طرف اس کو منسوب کرے اور امر وہ ہے جو بلا توسط اسباب خالص خدائے تعالی کی طرف سے ہو اور کسی سبب کی اس سے آمیزش نہ ہو۔

“The answer is that all these thoughts are God’s creation (khalq Allah), not God’s Command (amr Allah), and there is a subtle distinction between khalq and amr. Khalq refers to that act of God whereby God Almighty, being the Cause of all causes, creates something in the universe through the medium of causes and attributes it to Himself. And amr is that which proceeds directly from God Almighty, without the medium of causes, and with which no cause is intermixed.”3

Within this specific theological lexicon, khalq is assigned a precise and technical definition. Its defining characteristic is its operation through the medium of secondary causes (ba-tawassut-e asbab). It is the domain of mediated divine action, a process wherein God operates through the very chains of causality He has established. The Promised Messiahas further refines this concept, associating khalq not with absolute origination but with the act of fashioning a composite entity (murakkab) from pre-existing forms or elements – a process of transformation that occurs within time and space.

اور اگر ایسے طور سے کسی چیز کو پیدا کرے کہ پہلے وہ چیز کسی اور صورت میں اپنا وجود رکھتی ہو تو اس طرز پیدائش کا نام خلق ہے […] مرکب چیز کو کسی شکل یا ہیئت خاص سے متشکل کرنا عالم خلق سے ہے

“And if He creates a thing in such a way that the thing previously existed in some other form, then this mode of origination is called khalq […] to fashion a composite thing into a particular shape or form is from the realm of khalq.”4

Set in direct contradistinction to this mediated domain of causality is the concept of amr – an affair proceeding directly from God’s will without the intercession of any secondary causes or temporal processes, representing not creation through sequence but effectuation by pure command. This is the ontological reality behind the Quranic formula:

كُن فَيَكُونُ

“‘Be,’ and it is.”5

This is a command whose effectuation is described as being without suspension or delay (tawaqquf nahin hota), an instantaneous manifestation of divine intent that stands outside the sequential logic of khalq.

The Promised Messiahas clarifies this immediacy:

جو چیز علل اور اسباب سے پیدا ہوتی ہے وہ خلق ہے اور جو محض کُنْ سے ہو وہ امر ہے […] عالم امر میں کبھی توقف نہیں ہوتا

“That which is produced through causes and means is khalq and that which comes into being merely through kun [be] is amr […]. In the realm of amr, there is never any suspension.”6

This concept is further delineated by distinguishing between the legislative command (amr shar‘i), to which a created being may or may not conform, and the irresistible cosmic or ontological command (amr kawni), which is an absolute decree that cannot be contravened, as seen in the command to the fire concerning the Prophet Abrahamas.

The Promised Messiahas says:

دوسرے اوامر کونی ہوتے ہیں جس کا خلاف ہو ہی نہیں سکتا۔ جیسا کہ فرمایا يَٰنَارُ كُونِي بَرۡدٗا وَسَلَٰمًا عَلَىٰٓ إِبۡرَٰهِيمَ (الانبیاء:۷۰)۔ اس میں کوئی خلاف نہیں ہو سکتا۔ چنانچہ آگ اس حکم کے خلاف ہر گز نہ کر سکتی تھی۔

“Secondly, there are the cosmic commands (awamir kawni), which cannot be opposed. For instance, when He commanded, ‘O fire, be thou cold and a (means of) safety for Abraham!’7 There can be no opposition to this. Indeed, the fire could not act contrary to this command in any way.”8

The direct and unavoidable consequence of this meticulously established framework is the decisive placement of Divine Speech outside the created order. Having defined the terms, the Promised Messiahas applies them with analytical finality, asserting that the Quran, as God’s Speech, does not belong to the category of created things but originates from the higher, unmediated realm of divine command.

The Promised Messiahas states with explicit clarity:

پس کلام الہی جو اس قادر مطلق کی طرف سے نازل ہوتا ہے اس کا نزول عالم امر سے ہے نہ عالم خلق ہے۔

“Thus, Divine Speech which is sent down from that Absolute All-Powerful One, its descent is from the realm of amr and not from the realm of khalq.”9

This entire theological construct is not presented as a standalone philosophical innovation but is explicitly grounded in the text of the Quran itself, specifically in a verse that has historically served as the scriptural anchor for this very argument within mainstream Islamic thought. The Promised Messiahas roots his entire framework in the classical proof-text:

أَلَا لَهُ ٱلۡخَلۡقُ وَٱلۡأَمۡرُ

“Verily, His is the creation and the command.”10

The analytical force of the verse, as understood within this tradition, comes from the conjunction “and” (wa), which separates “the creation” (al-khalq) and “the command” (al-amr) into two distinct categories belonging to God, a line of reasoning, it is worth observing, that directly mirrors the primary scriptural proof used by classical Sunni authorities like Sufyan ibn ‘Uyayna and Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal to affirm that the Quran is uncreated.

The Promised Messiahas explains the verse’s implication as follows:

اَلَا لَهُ الْخَلْقُ وَالْاَمْرُ یعنے بسائط کا عدم محض سے پیدا کرنا اور مرکبات کو ظہور خاص میں لانا دونوں خدا کا فعل ہیں اور بسیط اور مرکب دونوں خدائے تعالیٰ کی پیدائش ہے

“‘Verily, His is the creation and the command,’ i.e., to create simple substances from absolute non-existence and to bring composite things into a specific manifestation are both acts of God and both simple and composite things are the creation of God Almighty.”11

By identifying the Quran as an instance of amr, the argument logically concludes that it cannot, therefore, be an instance of khalq.

Explicit statements on the uncreated nature of the Quran

While the metaphysical distinction between amr and khalq provides the foundational framework for the Ahmadi position, the argument does not rest on this conceptual basis alone. It is further substantiated by explicit and categorical statements from the Jamaat’s earliest leadership that directly address the nature of the Quran in unambiguous, creedal terms. The most decisive of these declarations comes from Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Ira, who, in the course of his scriptural exegesis, makes a clear statement of his personal belief on the matter, leaving no room for speculation.

While interpreting a verse that some might use to argue for the Quran’s createdness, he pre-empts this by stating his position directly:

ذِكْرٍ مُحْدَثٍ کے معنے ہیں نئے نئے پیرایوں میں کلام بھیجتے رہے۔ یہی معنے صحیح ہیں کیونکہ کلام کو میں اللہ تعالی کی صفت مانتا ہوں اورمتکلم خدا کی ذات ہے اور میں قرآن مجید کو مخلوق نہیں مانتا

“The meaning of dhikr muhdath is that He continued to send Speech in ever-new styles (na’e na’e payrayun mein). This is the correct meaning, because I consider Speech (kalam) to be an attribute (sifa) of God Almighty and the Speaker (mutakallim) is the Essence of God and I do not believe the Noble Quran to be created (makhluq nahin manta).”12

This statement is of considerable theological weight, containing as it does the two central pillars of the classical traditionalist argument: first, that the Quran’s essence is an eternal attribute (sifa) of God and second, the necessary conclusion that it is, therefore, not created. He approached this same conclusion from another, philosophically rich angle by identifying Divine Speech (kalam-e-ilahi) with the concept of the “Spirit” (ruh). Having established this equivalence, he proceeds to make a definitive ontological statement about its nature – namely, that this Spirit is not a created entity but an attribute of God Himself.

In his work Tasdiq Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya, his reasoning culminates in this declaration:

روح کو کتب مقدسہ اور پاک کتاب قرآن کریم نے بہت معنوں پر استعمال کیا ہے۔ اوّل، روح کلام الہی کا نام ہے۔ […] ان معنے کے رو سے روح مخلوق نہیں بلکہ اللہ تعالیٰ کی ایک صفت ہے اس لئے کہ یہ روح الہی کلام ہے اور اللہ تعالی اس کا متکلم

“The Holy Scriptures and the pure book, the Noble Quran, have used the word ruh for many meanings. Firstly, ruh is the name for God’s Speech. […] In this meaning, the ‘Spirit’ (ruh) is not created (makhluq nahin) but is an attribute (sifa) of God Almighty, because this Spirit is the Divine Speech (kalam) and Allah Almighty is its Speaker (mutakallim).”13

These direct affirmations from Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Ira are themselves aligned with the technical vocabulary employed by the Promised Messiahas, who used a term that carries immense weight and historical significance in this precise context. In describing the Quran’s pre-temporal existence in the Preserved Tablet (lawh mahfuz), he uses the word qadim, a term which, within the lexicon of this historic controversy, functions as the direct antithesis to hadith, i.e., contingent or created, and is synonymous with the ghayr makhluq position.

In A’ina-e-Kamalat-e-Islam, he states:

قرآن کریم جس کی خلق اللہ کو بہت ضرورت تھی اور جو لوح محفوظ میں قدیم سے جمع تھا تئیس سال میں نازل ہوا

“The Noble Quran, whose creation was greatly needed by God’s creation (jis ki khalqullah ko bahut zarurat thi) and which was eternally (qadim) collected in the Preserved Tablet, was revealed over twenty-three years.”14

The deliberate selection of the term qadim, i.e., eternal or pre-existent, represents a conscious act of theological positioning, one that bypasses ambiguity and directly situates his doctrine within the lexical and conceptual framework of the historical ghayr makhluq stance by affirming the Quran’s pre-existence before the creation of the temporal universe.

Framing the debate: The central question and its historical symbol

The dense and multi-faceted statement from Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIra presented in the introduction serves as the primary lens for understanding how the Ahmadi leadership framed this historic debate. By positing the relationship between God’s Speech and God’s Knowledge as the central point of investigation, he demonstrates an acute and theologically precise understanding of the classical debate’s core problematic. His question thus functions as a guide, directing the inquiry towards the specific theological premises upon which the ghayr makhluq position is constructed, for in that historical context, to affirm that Speech is an expression of God’s eternal and uncreated Knowledge is, by logical necessity, to affirm that Speech itself must partake in that same uncreated nature.

The immediate invocation of Imam Ahmad’s persecution within the same breath is not incidental. It frames the ghayr makhluq stance as the one for which the righteous have historically suffered. This veneration is not an isolated reference but a consistent theme. In a separate Friday Sermon, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIra again held up the Imam as a heroic exemplar, clarifying his creed with explicit approval:

خلق قرآن کے مسئلہ پر بحث ہوئی تو امام احمد بن حنبل نے مار کھا کر اپنے ہاتھ تڑوا لیے مگر بادشاہ سے دبے نہیں۔ وہ یہی کہتے رہے کہ قرآن مخلوق نہیں مقول ہے۔ یعنی یہ خدا تعالیٰ کا قول ہے۔ کوئی ایسی چیز نہیں جو پیدا کی گئی ہو۔

“When the issue of the createdness of the Quran was debated, Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal was beaten and had his arms broken, but he did not yield to the king. He kept insisting that the Quran is not created (makhluq nahin), it is Speech (maqul hai). Meaning, it is God Almighty’s Speech, not something that came into existence.”15

The significance of this praise is amplified when, in the next paragraph, he elevates Imam Ahmad to a status akin to the Companionsra of the Prophet Muhammadsa, applying to him the famous hadith that they are like “guiding stars” from whom a world obtains guidance. To consistently lionise the primary historical champion of the ghayr makhluq doctrine and to do so by specifically highlighting his steadfastness on that very issue functions as a powerful rhetorical and theological endorsement.

The Ahmadi position notably avoids the sectarian extremism that characterised the classical debates. The Promised Messiahas explicitly recognised the Mu‘tazila as remaining within the fold of Islam despite their position on this issue:

ولا شك أنهم من المذاهب الإسلامية

“There is no doubt that they are among the Islamic schools.”16

This irenic approach – respecting those who defended the Quran’s uncreated nature while refusing to anathematise those who held different views – distinguishes the Ahmadi position from the mutual excommunications that characterised the classical period.

The theological framework: The Quran as a divine attribute

While the historical framing of the debate demonstrates the high stakes and pious alignment of the Ahmadi position, the intellectual core of the doctrine rests upon a deeper theological principle concerning the nature of God’s attributes (sifa). The explicit statements affirming the Quran’s uncreatedness are not isolated pronouncements but the direct and necessary consequence of this principle, which was articulated with definitive clarity by the Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIra, when directly questioned on this matter – a format that leaves little room for interpretive ambiguity. His response serves as the foundational premise for the entire argument: that all of God’s attributes are co-eternal with His Essence and are, therefore, not created.

The exchange was as follows:

سوال: خدا کی صفات اس کے ساتھ ہی ازلی ہیں یا پیدا شدہ؟

جواب: صفات الٰہیہ مخلوق نہیں ہیں بلکہ وہ ذات کے ساتھ ہی ازلی ابدی ہیں۔

Question: “Are the attributes of God co-eternal with Him or are they created?”

Answer: “The attributes of God are not created (makhluq nahin hain). Rather, they are co-eternal and co-everlasting (azali abadi hain) with His Essence (dhat).”17

With this axiom established, the argument proceeds by identifying the Quran not as a created object separate from God, but as the tangible manifestation of one of these eternal, inherent attributes – namely, the attribute of Speech (kalam).

This direct application of the doctrine of attributes to the Quran is made most forcefully by Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Ira who, in the creedal statement previously cited, identifies Speech (kalam) as an eternal attribute (sifa) as the very reason for his belief that the Quran is not created.

The logical integrity of this framework, which posits an eternal attribute manifesting in time, depends on resolving a classical theological problem: if Speech is eternal, why is revelation not perpetual? The Promised Messiah’sas writings address this directly by drawing a fine distinction between the permanent suspension of an attribute (ta‘attul dai’mi), which he deems impossible for a perfect Being, and its temporary non-manifestation according to divine will (ta‘attul mi‘adi), which he affirms is permissible. God remains eternally the Speaker, even if He is not revealing new scriptures at every given moment.

He explains this principle in his work Chashma-e-Ma‘rifat:

کسی صفت کے لئے تعطّل دائمی جائز نہیں ہاں تعطّل میعادی جائز ہے

“For any [Divine] attribute, permanent suspension (ta‘attul da’imi) is not permissible, though temporary suspension (ta‘attul mi‘adi) is permissible.”18

This concept directly addresses the core philosophical challenge posed by rationalist theologians like the Mu‘tazila: that an eternal attribute of Speech or Creation would necessitate an eternal audience or an eternal creation, thus implying the existence of other eternal entities alongside God and violating pure monotheism. The Promised Messiah’sas writings answer this objection with a sophisticated distinction between two types of eternality: the eternality of an individual (qadamat-e shakhsi), which he rejects for any created thing, and the eternality of a species or genus (qadamat-e naw‘i), which he affirms. This means that while no single universe or individual soul is co-eternal with God, the genus of creation, in some form, has always existed as a manifestation of God’s eternally active attributes.

The Promised Messiahas explains this as follows:

قدیم سے سلسلہ مخلوق کا اُس کے ساتھ چلا آیا ہے مگر کسی چیز کو اُس کے مقابل پر قدامت شخصی نہیں ہاں قدامت نوعی ہے۔

“From eternity, the chain of creation has run alongside Him, but no thing possesses individual eternality (qadamat-e shakhsi) in opposition to Him, yes, it does possess generic eternality (qadamat-e naw‘i).”19

This doctrine allows for God’s attributes to be eternally active in principle without necessitating that any specific, individual object of those attributes be co-eternal with Him, thereby resolving the apparent philosophical tension and preserving the principle of tawhid.

Resolving the theological status of the ‘Word’ as applied to creation

This rigid theological distinction between the eternal attribute (sifa) and its created result (khalq) provides the necessary framework to resolve a historical polemical objection often levelled against the doctrine of the uncreated Word. Christian theologians, most notably John of Damascus (d. 749), historically argued that if Muslims admit the Word of God (kalam Allah) is uncreated and the Quran acknowledges Jesusas as the “Word of God” (kalimat Allah), then Muslims must logically concede that Jesusas is uncreated and divine.

Foundational Ahmadi texts deconstruct this conflation by distinguishing between the Word as an eternal attribute and the Word as a title for a created entity. The Promised Messiahas argues that if the title “Word of God” implies uncreated divinity, then by the logic of the Quran, all souls would share in this status, for all souls are fundamentally words of command from the realm of amr.

He explains in Izala-e-Auham:

اس جگہ خدائے تعالیٰ نے روح کا نام کلمہ رکھا۔ یہ اس بات کی طرف اشارہ ہے کہ در حقیقت تمام ارواح کلمات اللہ ہی ہیں جو ایک لا یدرک بھید کے طور پر جس کی تہ تک انسان کی عقل نہیں پہنچ سکتی روحیں بن گئی ہیں۔

“Here, God Almighty has named the soul ‘Word’ (kalima). This points to the fact that, in reality, all souls are Words of God (kalimat Allah) which, through an inscrutable mystery that human intellect cannot reach, have become souls.”20

Furthermore, he argues that even entities emerging from the realm of Command (amr) are not the Divine Essence itself but are shadows (zill) or effects of the Command. Here, a crucial distinction must be made between amr as an uncreated Divine Attribute, i.e., the eternal power to Command, and the objects of that Command, i.e., souls or spirits. While the attribute is uncreated, the resultant Spirit is explicitly defined as created (hadith) and a servant of God, possessing no share in divinity.21

If the term “Spirit from Him” (ruh minhu) implied being a part of God’s uncreated essence, then Adamas would have a superior claim to divinity than Jesusas, for the Quran describes the Divine Spirit being breathed directly into Adamas.22

The Promised Messiahas writes:

فيجب أن يكون مقام آدم أرفع منه وأعظم، ويكون آدم أول أبناء ربّ العالمين […]. فإن منطوق الآية يدل علی أن روح الله نزل فی آدم بنزول أجلى

“[T]hen it follows that the status of Adam must be higher and greater than that of Jesus. Adam would be the first of the sons of the Lord of all the worlds […]. The above-mentioned verse indicates that the Spirit of Allah descended into Adam, and that this was a more luminous descent”.23

Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Ira addresses this objection by employing a reductio ad absurdum, noting that in scriptural idiom, the “Word of God” often refers to specific prophecies or commands. If being a “Word” made the recipient uncreated, then the entire creation would lay claim to godhood.

He writes in Ibtal-e uluhiyyat-e Masih:

اگر قرآنی محاورہ سے کسی چیز کا کلمۃ اللہ ہونا اس چیز کے خدا ہونے کی دلیل ہے تو تمام کلمات الہیہ کو چاہئے کہ خدا ہوں […] اگر کوئی چیز کلمۃ اللہ ہونے سے عین اللہ ہو سکتی ہے تو تمام وہ تامہ جملے جو انبیاء علیہم السلام اور ان کے پاک اتباع کو مکالمہ الہیہ اور مخاطبہ ربانیہ سے پہنچے چاہئے کہ وہ سب خدا ہوں۔

“If in the idiom of the Holy Quran something being called the kalimat Allah, ‘the word of Allah’ is an argument in support of that thing being God, then all the words of Allah would have to be God. […] If something could be Allah precisely by virtue of being kalimat Allah, then all those complete sentences that came to the prophets, peace be upon them all, and their holy followers by way of Divine discourse and communications from their Lord, should all be God.”24

He concludes that Jesusas is called “Word” specifically because his birth was the result of a specific verbal prophecy (kalam) delivered to Maryas. In neither case does the recipient of the Command become the Command itself. As Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Ira states in Tasdiq Barahin-e Ahmadiyya, Jesusas remains “His creature (makhluq)”, distinct from the uncreated attribute that brought him into being.25

Addressing nuances and apparent contradictions

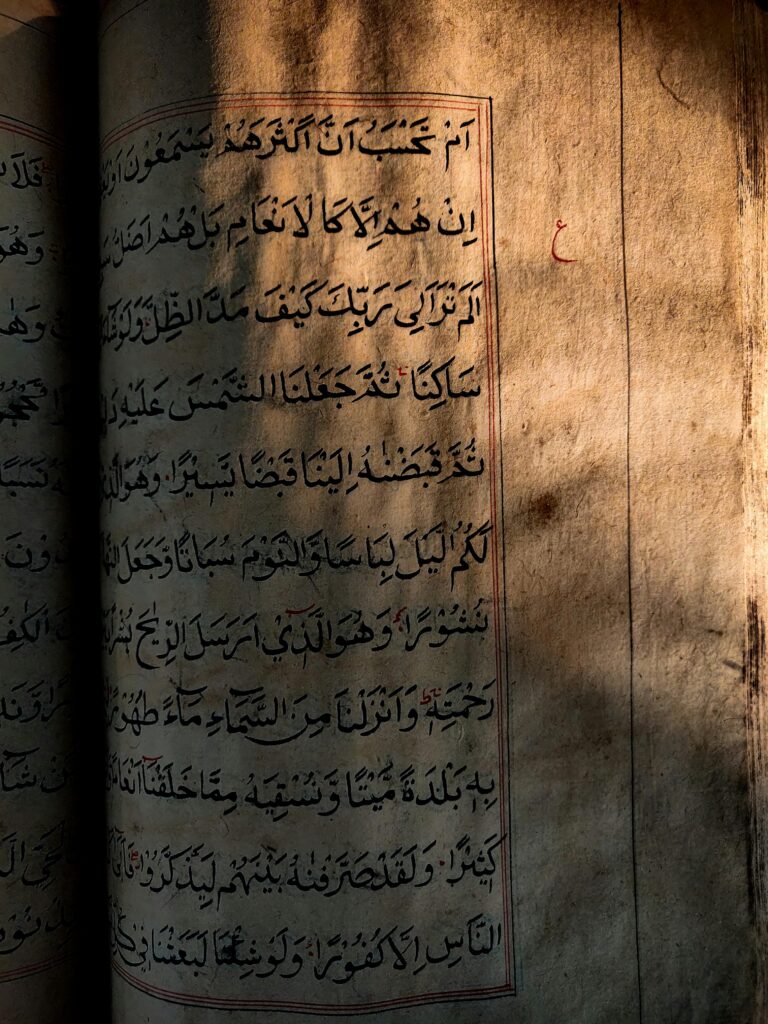

The sophistication of the Ahmadi position is demonstrated not merely in its foundational affirmations but in the capacity of its primary sources to address the nuanced questions that arise from the doctrine of an uncreated Quran. The conceptual groundwork for understanding how eternal, uncreated Speech can be received by a temporal, created being is laid by the Promised Messiahas himself. He describes the revelatory process as one that requires the complete suspension of the prophet’s created human faculties to ensure the purity of the divine transmission.

The Promised Messiahas explains this in his work Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya:

خدا کا پاک کلام وہ کلام ہے کہ جو انسانی قویٰ سے بکلی برتر و اعلیٰ ہے۔ […] جس کے ظہور و بروز کے لئے اول شرط یہی ہے کہ بشری قُوَتیں بکلّی مُعطّل اور بیکار ہوں نہ فکر ہو نہ نظر ہو۔ بلکہ انسان مثل میّت کے ہو۔ اور سب اسباب منقطع ہوں اور خدا جس کا وجود واقعی اور حقیقی ہے آپ اپنے کلام کو اپنے خاص ارادہ سے کسی کے دل پر نازل کرے۔

“God’s pure Speech is that Speech which is completely superior and exalted above human faculties. […] The first condition for its appearance and manifestation is that human faculties (bashari quwwaten) be completely suspended (mu‘attal) and useless (be-kar). There should be neither thought (fikr) nor reflection (nazar). Rather, the person should be like a corpse (mithl-e mayyit ke ho) and all means should be cut off. And God, whose existence is real and true, Himself sends down His Speech upon someone’s heart by His special will.”26

This description of the prophet as a passive recipient – “like a corpse” – whose own created faculties of “thought” and “reflection” are rendered “useless,” provides a direct explanation for how uncreated Divine Speech can be received by a created being without being admixed with created human elements. The process itself purifies the channel, ensuring the Speech remains purely divine in its transmission.

This nuanced understanding extends to the mechanics of revelation itself. The founder’s writings bypass the paradox of an eternal entity entering the contingent world by defining the process not as the physical transport of an object but as a purely spiritual influence or manifestation – a process for which he uses the specific theological term tamaththul.

The Promised Messiahas explains in his work A’ina-e-Kamalat-e-Islam:

اگر یہ لوگ اس بات کو قبول کر لیتے کہ کوئی فرشتہ بذات خود ہر گز نازل نہیں ہوتا بلکہ اپنے ظلی وجود سے نازل ہوتا ہے جس کے تمثل کی اس کو طاقت دی گئی ہے […] اور جیسا کہ حضرت مریم کے لئے فرشتہ متمثل ہوا تو کوئی اعتراض پیدا نہ ہوتا

“If these people were to accept that no angel ever descends in its own person, but rather descends through its shadowy existence (zilli wujud), for which it has been given the power of manifestation (tamaththul) […] and just as the angel manifested (mutamaththil hu’a) for Mary, then no objection would arise.”27

This non-physical process is further illustrated with the analogy of the sun, which remains fixed in its station while its light and energy spread across vast distances.

As the Promised Messiahas clarifies:

محققین اہل اسلام ہرگز اس بات کے قائل نہیں کہ ملائک اپنے شخصی وجود کے ساتھ انسانوں کی طرح پیروں سے چل کر زمین پر اترتے ہیں […] اصل بات یہ ہے کہ جس طرح آفتاب اپنے مقام پر ہے اور اُس کی گرمی و روشنی زمین پر پھیل کر اپنے خواص کے موافق زمین کی ہر یک چیز کو فائدہ پہنچاتی ہے اسی طرح روحانیات سماویہ […] اپنے اپنے مقام میں مستقر اور قرار گیر ہے

“The accomplished scholars of Islam are by no means of the view that angels, with their personal existences, descend to the earth walking on their feet like humans. […] The real matter is that, just as the sun is in its place and its heat and light spread over the earth, benefitting every single thing on earth according to its properties, in the same way, the celestial spiritual beings […] are established and settled in their own respective stations.”28

This principled hermeneutic is demonstrated quite convincingly in the direct engagement of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Ira with a key verse that could be used to argue for the Quran’s createdness: Surah al-Anbiya’, Ch. 21: V. 3, which mentions the arrival of a dhikr muhdath or “new reminder.” Confronted with a term that implies temporal newness, he explicitly rejects the interpretation that this refers to an ontological creation. Instead, he argues that the “newness” pertains only to its phrasing and presentation for a new audience. The justification he provides for this exegesis is the crucial element, for, as seen in the full quotation already presented, he explicitly grounds his interpretation in the foundational doctrine by concluding his reasoning with the decisive clause: “because I consider Speech to be an attribute of God Almighty.” This passage is of singular importance, as it shows the ghayr makhluq doctrine operating not as a passive belief, but as an active, determinative principle of scriptural interpretation, used to resolve textual challenges in a manner that preserves the core theological position on the uncreated nature of divine Speech.

Philosophical reinforcements

The argument’s historical framing is complemented by several deep philosophical reinforcements articulated by the Promised Messiahas, beginning with a position that posits a direct correspondence between the infinite nature of the Creator and the properties of His unmediated Speech, for an effect cannot possess qualities that transcend its cause. The logic is that since the Quran displays limitless wonders, its source cannot be a finite, creative act but must be the infinite Divine Essence itself.

In his work Karamat as-Sadiqin, the Promised Messiahas develops this argument from infinity:

جو چیز غیر محدود قدرت سے وجود پذیر ہوئی ہے اس میں غیر محدود عجائبات اور خواص کا پیدا ہونا ایک لازمی اور ضروری امر ہے […] پس کیونکر قرآن کریم جو خدا تعالی کا پاک کلام ہے صرف ان چند معانی میں محدود ہو گا

“It is a necessary and essential matter that a thing which has come into existence from an infinite Power (ghayr mahdud qudrat) should possess infinite wonders and properties (ghayr mahdud ‘aja’ibat). […] How, then, can the Holy Quran, which is God Almighty’s pure Speech, be limited to only those few meanings?”29

Finally, the founder establishes the high theological stakes of this debate, concluding the very same foundational exposition on amr and khalq that was detailed before with a stern warning against the alternative view. He argues that to categorise Divine Speech as khalq is to effectively reduce it to the level of human thought, a reduction that leads to a grave theological error bordering on disbelief (kufr), for it implies that the infinite knowledge of God can be fully contained within the finite vessel of the human mind – an implication which is, in its essence, a claim to divinity.

He explains this critical point in Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya:

اس سے زیادہ تر اور کیا کفر ہو گا کہ انسان ایسا خیال کرے کہ جس قدر خدا کے پاس خزائن علم و حکمت اور اسرار غیب ہیں وہ سب ہمارے ہی دل میں موجود ہیں اور ہمارے ہی دل سے جوش مارتے ہیں۔پس دوسرے لفظوں میں اس کا خلاصہ تو یہی ہوا کہ حقیقت میں ہم ہی خدا ہیں

“What greater disbelief (kufr) could there be than for a person to imagine that all the treasures of knowledge, wisdom and unseen mysteries that God possesses are present within our own heart and gush forth from our own heart? In other words, its summary is just this: that in reality, we ourselves are God.”30

This concluding argument frames the ghayr makhluq position not merely as a preferred opinion, but as a necessary safeguard for the absolute transcendence of God and the core principle of pure monotheism (tawhid).

Conclusion

The cumulative weight of the textual evidence, drawn directly from the writings of the Promised Messiahas and his immediate Successors, presents a clear and internally consistent theological position regarding the nature of the Quran. This position is built upon a foundational metaphysical distinction between the unmediated Divine Command (amr) and the realm of mediated creation (khalq), it is substantiated by direct, creedal affirmations of the Quran’s uncreated (ghayr makhluq) and eternal (qadim) nature and it is rooted in the theological principle that the Quran is the manifestation of an uncreated divine attribute (sifa) of Speech. The doctrine’s integrity is maintained through sophisticated resolutions to apparent philosophical and textual challenges – including the differentiation between the eternal attribute of Speech and its created recipients – as well as concepts such as generic eternality (qadamat-e naw‘i) and the temporary suspension of divine attributes (ta‘attul mi‘adi).

This entire intellectual structure is further reinforced by a consistent historical alignment with the traditionalist camp, evidenced by a distinct veneration for Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal, and is ultimately presented as a necessary bulwark for safeguarding the absolute transcendence of God. This comprehensive theological edifice stands in direct opposition to the statement reported by AJ Arberry, suggesting that the comment from the imam of the London mosque may have represented a misunderstanding or an incomplete articulation of a complex doctrine – perhaps mistaking the contingent nature of the Quran’s temporal manifestation for a denial of the uncreated nature of its essential, divine reality. The textual record itself, however, remains unambiguous, demonstrating that the Ahmadi position upholds the doctrine of the uncreated Quran not merely as a point of classical dogma, but as a necessary consequence of its understanding of divine unity, action and revelation.

Endnotes

1. A. J. Arberry, Religion in the Middle East: Three Religions in Concord and Conflict (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969), Vol. 2, p. 352.

2. Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad, Fada’il al-Quran, in: Id., Anwar-ul-Ulum (Qadian: Nazarat-e Nashr-o-Ishaʻat, 2008), Vol. 10, p. 503. It is historically noted that while Huzoor’sra statement speaks of the Imam having “passed away”, Imam Ahmad in fact survived the ordeal. He endured 28 months of imprisonment and torture, was eventually released and resumed his teaching for many years before his death in 241/855.

3. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Barahin-e Ahmadiyya: Part 3, in: Id., Ruhani Khazain (Farnham: Islam International Publications, 2021), Vol. 1, p. 235.

4. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Surma-e Chashm-e Arya, in: Id., Ruhani Khazain (Farnham: Islam International Publications, 2021), Vol. 2, pp. 175-176.

5. This formulation appears at least eight times throughout the Quran, for instance, Surah Ya Sin, Ch. 36: V. 83.

6. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Malfuzat (Farnham: Islam International Publications, 2022), Vol. 5, p. 75.

7. Surah al-Anbiya’, Ch. 21: V. 70.

8. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, ibid., pp. 182-183.

9. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Barahin-e Ahmadiyya: Part 3, ibid.

10. Surah al-A‘raf, Ch. 7: V. 55.

11. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Surma-e Chashm-e Arya, ibid., p. 176.

12. Hazrat Hakeem Noor-ud-Deen, Irshadat-e Nur (Rabwah: Nazarat-e Isha‘at, 2015), Vol. 2, p. 456.

13. Hazrat Hakeem Noor-ud-Deen, Tasdiq Barahin-e Ahmadiyya (Rabwah: Nazarat-e Isha‘at, 2015), p. 182.

14. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, A’ina-e-Kamalat-e-Islam, in: Id., Ruhani Khazain (Farnham: Islam International Publications, 2021), Vol. 5, p. 306.

15. Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad, Khutbat-e Mahmud (Rabwah: Fazl-e Umar Foundation, 2017), Vol. 38, p. 152.

16. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Itmam al-Hujja, in: Id., Ruhani Khaza’in (Farnham: Islam International Publications, 2021), Vol. 8, p. 279.

17. Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad, Farmudat-e Musleh-e Maud: Darbarah Fiqhi Masa’il (Rabwah: Nazarat-e Isha‘at, 2013), p. 3.

18. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Chashma-e-Ma‘rifat, in: Id., Ruhani Khaza’in (Farnham: Islam International Publications, 2021), Vol. 23, p. 272.

19. Ibid.

20. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Izala-e-Auham, in: Id., Ruhani Khaza’in (Farnham: Islam International Publications, 2021), Vol. 3, p. 333.

21. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Surma-e Chashm-e Arya, ibid., p. 173.

22. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Nur-ul-Haqq: Part 1, in: Id., Ruhani Khaza’in (Farnham: Islam International Publications, 2021), Vol. 8, pp. 135-136.

23. Ibid.

24. Hazrat Hakeem Noor-ud-Deen, Ibtal-e uluhiyyat-e Masih (Qadian: Matba‘-e Diya’ ad-Din, 1904), pp. 19-20.

25. Hazrat Hakeem Noor-ud-Deen, Tasdiq Barahin-e Ahmadiyya (Rabwah: Nazarat-e Isha‘at, 2015), p. 183.

26. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Barahin-e Ahmadiyya: Part 3, ibid., p. 236.

27. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, A’ina-e-Kamalat-e-Islam, ibid., p. 96.

28. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Taudih-e Maram, in: Id., Ruhani Khaza’in (Farnham: Islam International Publications, 2021), Vol. 3, pp. 66-68.

29. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Karamat as-Sadiqin, in: Id., Ruhani Khaza’in (Farnham: Islam International Publications, 2021), Vol. 7, p. 60.

30. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Barahin-e Ahmadiyya: Part 3, ibid., p. 237.