Fazal Masood Malik and Farhan Khokhar, Canada

Governments and powerful institutions in developing nations have a troubling propensity for abusing their authority to undermine citizens’ fundamental rights. This suppressive tendency mainly targets minority religious and ethnic groups. Pakistan presents a notable example, as evident in how election laws disenfranchise the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community—stripping away their fundamental democratic right to vote.

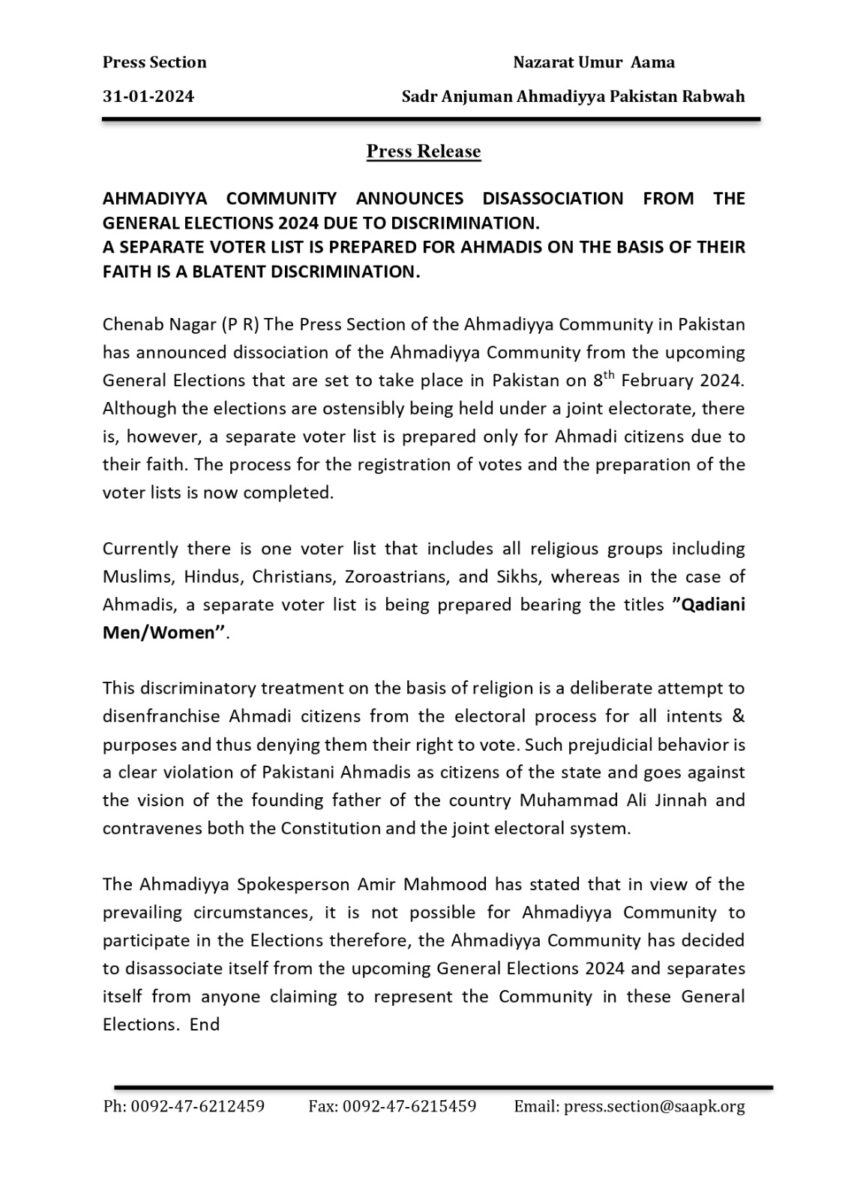

As Pakistan gears up for the 2024 general elections, voter regulations specifically disadvantage Ahmadi citizens in a deliberate attempt at systemic exclusion. Ahmadi Muslims are treated as a separate electorate, with voter lists marked as “Qadiani Men and Women” to segregate them from the general voter roll. This two-tiered system revokes civic rights that ultimately bar Ahmadi Muslims from participating meaningfully in the elections. In protest, the Community has declared it will disassociate entirely from the polls rather than consent to such discrimination.

The underlying drivers and motives here may be complex, steeped in religious clerical politics and constitutional manoeuvres dating as far back as the 1970s. However, the outcome clearly contradicts the principles of equitable treatment. By placing administrative hurdles on Ahmadi voting, based solely on their religious identity, institutions like Pakistan’s Election Commission essentially overstep their power, employing it to disempower and marginalise.

This tendency towards suppressive conduct by governing agents escalates in countries whose foundations lie in religious or nationalistic ideologies, especially where deep polarisation exists between majority and minority adherents. Ironically, such majority-based exercising of authority ultimately weakens the integrity of democratic functions for all citizens, irrespective of belief systems. As the unchecked power vested in agencies grows, pathways for people to recoup break down, ultimately creating societal breakdown. This is why political power must be shared.

Moreover, since electoral processes form the bedrock of representative governance, selectively barring subsets of citizens from inclusion strikes at the heart of a pluralistic system. Here, decision-makers should reflect the diversity of constituencies. Ahmadi Muslims and others subject to unequal treatment become doubly disempowered—locked out of elections as well as governance policymaking. Such excluded groups can then only rely on civic leaders and judicial redress for recourse. However, the leaders of these institutions are often uninterested in extending civic rights or confronting bigoted clerics.

Pakistan presents a prominent example of intertwined democratic and non-democratic tendencies, where executive directives, electoral rules, and government agency workflows layered over a parliamentary base routinely undermine citizen accountability. Similar patterns unfurl elsewhere, too, whether against Kurds in Turkey, Uighur Muslims in China, Muslims in India, or migrant refugees in Hungary.

As Pakistan’s institutions and administrative organs have evidenced, there exists a constant tension between expanding authority and preserving citizens’ rights. Western democracies faced this, too, with their legacy of slavery, segregation, and disenfranchisement along racial lines or loyalty tests. That dark phase took generations of activism and moral awakening to rectify into today’s relatively more equitable civic ecosystem.

Safeguarding rights requires continuous vigilance, even in developed democracies. Public institutions, to a large extent, act as a barricade against extremism and the tyranny of the majority. Complacency is not an option.

For multi-religious, post-colonial states like Pakistan, the path forward lies in reconciling diversity and democracy by protecting—not suppressing—pluralism. The yardstick for governing authorities cannot be the loudest, majority-based voice but rather universal human rights.

The treatment of Ahmadi Muslims and their voting predicament will serve as a critical test case. It is challenging for institutions to take ethical positions and serve as moral guides when they cater to violent clerics dictating popular ideologies. But where courage and conscience exist, opportunities for progress inevitably emerge. This represents the only hope for a progressive society.

[Note: Last week, Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya issued the following press release on the above issue of Ahmadis’ exclusion from Pakistan’s upcoming general elections, being held on Thursday, 8 February 2024.]