Asif M Basit, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre

Much has been written about Indian pilgrims to Mecca and Medina in the colonial days, but most of such investigation has revolved around the political interaction of various territories and their colonial masters. Discussions on epidemics are also a favourite topic, but that too is mostly rooted in geopolitical interests and concerns around border controls and measures.

While debates around sectarian conflicts have found some space in the colonial-Hajj literature, a community almost never mentioned is the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community that underwent restrictions and hardships from not only their co-religionists, but also the states involved in the process.

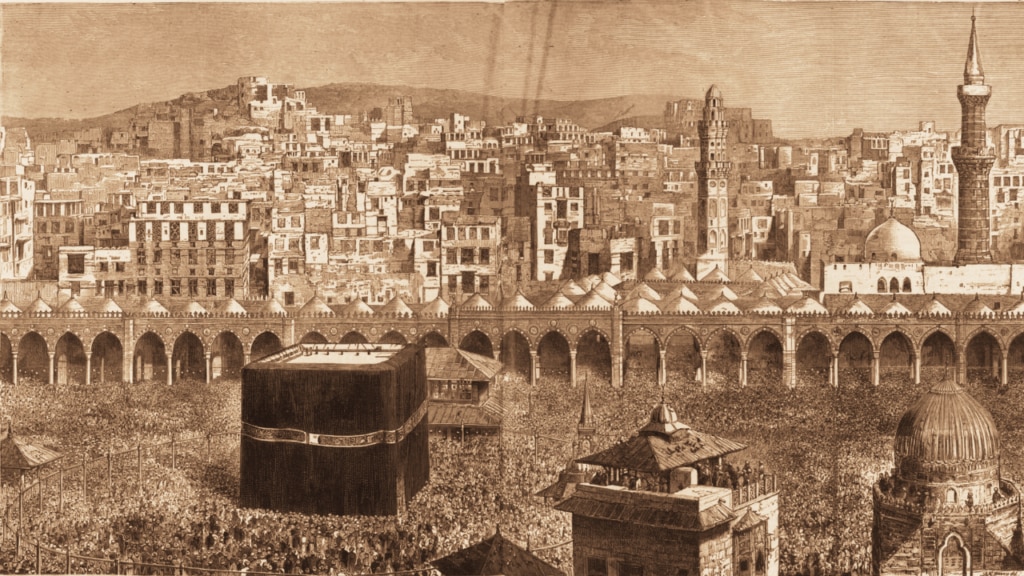

Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra, Son of the Founder of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, undertook the journey to perform Hajj in late 1912. This was two years prior to him taking on the caliphate of his late father Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas of Qadian. He was accompanied by his maternal grandfather, Hazrat Mir Nasir Nawabra, and another companion by the name of Abdul Mohyi Arab.

He left Qadian on 26 September 1912, boarded the ship to Port Said from Bombay (16 October), and arrived in Mecca via Jeddah on 7 November.

Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra and his entourage had undertaken this journey to perform Hajj and, alongside, to propagate the message of Ahmadiyyat in the Holy lands of Mecca and Medina.

The Ahmadiyya community reported on his journey based on the letters he wrote to Hazrat Hakeem Noor-ud-Deenra, then the caliph of the Ahmadiyya community in Qadian, en route and during his stay in Hijaz.

Newspaper reports suggest that he remained busy in preaching Islam right from the very start, where he often spoke to several atheists while aboard the ship. While in transit at Port Said, he had a meeting with the Shaikh-ul-Islam of the area, where Abdul Mohyi Arab, for his command on the Arabic language, introduced the Shaikh to Ahmadiyya beliefs with special reference to the death of Prophet Jesusas.

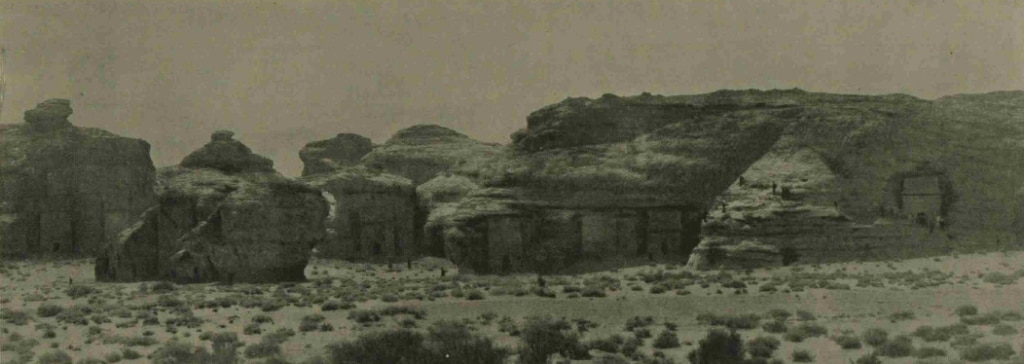

He remained busy in tabligh (proselytising) while staying in Jeddah1, before departing for Mecca on camelback.

Hazrat Mahmud Ahmadra soon got recognised, and the news that he was in Mecca spread quite rapidly.2 As he walked the streets, some would point towards him, saying “Ibn Qadiani”, or the son of Qadiani.3

Some Indians from Bhopal – one of them his distant maternal uncle and another from the nobility, named Khalid – had launched a campaign against Hazrat Mahmud Ahmadra, claiming that he and his associates were spreading kufr in the holy lands of Hijaz.

This he had found out from a scholar, namely Abdus Sattar Kibti, whom he preached and invited to accept Ahmadiyya Islam. Kibti warned him not to go about doing tabligh, as some mischief-makers had even put up posters against him and his entourage; the public could hence be in a rage and could resort to violence.

Kibti also informed him that the two men had also incited the government of Hijaz to take action against the “Qadianis”.4

This reminded Hazrat Mahmud Ahmadra of a debate he had had earlier that day, with a scholar who, after listening, had said that had there been a sword available, he would have beheaded him straight away.5

Despite the precarious circumstances, he also had a meeting with the Sherif of Mecca,6 the details of which are not known.

Reminiscing about his Hajj experience almost a decade later, Hazrat Mahmud Ahmadra once stated:

“Back then, the authorities could arrest anyone they wished, but I did tabligh quite a lot and quite openly. However, after the day we left Mecca, the house where we had stayed was raided, the landlord taken into custody and questioned about our whereabouts.”7

With the outbreak of cholera in Hijaz, the entourage had to sail back to India on the next available ship.

Ottomans behind the scenes

This persecution that had taken Hazrat Mahmud Ahmadra by surprise had not just emerged out of nowhere. The stage had been set even before they set foot on the ship from Bombay.

As the entourage boarded the Hijaz-bound ship on 16 October 1912, the Ottoman Ministry of Foreign Affairs at Istanbul had sent a communique to the Ministry of Interior Affairs of the Hijaz, on the very same day:

“Sublime Porte

“Ministry of Foreign Affairs

“General Directorate of Political Affairs

“Number: –

“Bombay Consulate dated 16 October.

“Mirza Ghulam [sic. Bashir-ud-Din] Mahmud Ahmed, the 23-year-old son of Mirza Ghulam Ahmed, who is from Qadian Town of Punjab and claimed to be the Mahdi while he was alive, left for Hijaz yesterday with his entourage to perform the hajj. Mahmud Ahmed is accompanied by a man named Abdulhay ibn Abdullah. This man is from Hille (حله) but in reality, he is from Hilye (حلیە). When he applied for a passport at the consulate, he was asked to bring a witness to prove his identity. Then, when he tried to get a visa with the passport he received from the Iranian consulate, it was understood that he had bad intentions, and his passport was detained for a while. Finally, we gave him a document. Although his book seems ordinary on the surface, its content is harmful. He is a follower of Hakim Nureddin, whom Ahmed left as caliph. His purpose in going to Hijaz is to spread his mezheb [sect]. Nuruddin has books claiming that Ahmed is the Mahdi. Ahmed has also written several books on the subject. However, I sent a letter to the Hijaz Province asking for measures to be taken to prevent these men from spreading sedition and distributing their books. To command belongs to him who commands all.”8

A reminder was sent a few days later by the same person to the same person, which carried more information. Where the earlier letter instructed for “measures to be taken to prevent these men from spreading sedition and distributing their books”, the reminder went a step ahead and instructed “to prosecute these men”:

“Sublime Porte

“Ministry of Foreign Affairs

“General Directorate of Political Affairs

“Number: 25475/1249

“To the Ministry of Interior

“Summary: About Mirza Ghulam Mahmud Ahmed from Punjab who came to Hijaz and his entourage.

“Mirza Ghulam [sic] Mahmud Ahmed, the son of Mirza Ghulam Ahmed, who was from Qadian town of Punjab and claimed to be the Mahdi while he was alive, came to Hijaz with his entourage on November 15 to perform the Hajj pilgrimage. Due to the negative information about Abdulhay [sic Abdul Mohyi] ibn Abdullah, one of Mahmud Ahmed’s entourage, his identity was investigated and one of the books he wrote was examined. It is highly probable that these men brought propaganda books with them. The Bombay Consulate sent a letter to prosecute these men so that they do not spread sedition and distribute books. We have sent you a copy of the letter from the Consulate. We request that your Ministry take the necessary action. December 2, 1912

“Undersecretary on Behalf of the Minister of Foreign Affairs.”9

It appears that, having received no response, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs continued to chase the matter with Hijaz through the following months and within the timeframe when Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra was still in Hijaz:

“Ministry of Interior Communications Department

“Branch 2

“Ref: 1249

“Date: 9 December 1912

“Ciphered telegram to the Province of Hejaz via Beirut.

“We expect you to inform us of the investigation you have made after receiving the letter sent to your province by the Bombay Consulate regarding Mirza Ghulam Mahmud Ahmed and his entourage from the people of Punjab.

“The document written by order of the Undersecretary is in the file at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.”10

Upon this follow-up query, the Ottoman governor of Hijaz wrote back to the Sublime Porte:

“Hejaz Province

“Register Office

“Ref: 100

“To the exalted Interior Ministry,

“My kind and exalted lord,

“This is the response to the coded telegram from your ministry dated 11 December 1912. We have not yet received any correspondence from the Bombay Consulate regarding Ghulam Mahmud Ahmed and his entourage. We have sent a letter to the Consulate and requested an explanation regarding this matter. We will do what is necessary depending on the response we receive. To command belongs to him who commands all.

“December 25, 1912

“Governor of Hijaz”11

As the readers would have observed, the issue was being treated as a high priority and communicated in code that needed deciphering.

To the above reminder, dated 9 December 1912, the Governor of Hijaz finally replied on 3 April 1913:

“Hejaz Province

“Register Office

“Ref: 24

“Summary: About Mirza Ghulam [sic] Mahmud Ahmed from Punjab and his entourage who came to Mecca during the last Hajj season and returned to their hometown without causing any trouble.

“To the exalted Interior Ministry,

“My kind and exalted lord,

“This is an annex to the official letter dated 25 December 1912 and numbered 100. Gulam Mahmud Ahmed from Punjab and his entourage arrived in Mecca at the beginning of the month of Dhul-Hijjah. After performing the Hajj, he went to Jeddah with his entourage on the 19th of the same month. The Jeddah administration reported that they did not cause any problems while they were there and then returned to their country. The Bombay Consulate General was also informed about this. To command belongs to him who commands all.

“3 April 1913

“Governor of Hijaz”12

It was not only the Foreign Ministry of the Ottoman Empire communicating with their Interior Ministry in Hijaz on this matter. Material held at the Ottoman Imperial Archives in Istanbul shows that the Grand Vizier, only second to the Ottoman Sultan, was also taking a keen interest in the matter of these “Qadianis”. The higher-ups at Sublime Porte were now looking into what Ahmadiyya was all about and what to expect from these men.

While Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra was in Mecca (7 November-25 December 1912), the Ministry of Internal Affairs wrote to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on 2 December 1912:

“Ministry of Internal Affairs

“General Communications Department

“Branch 2

“Ref: 1249

“Date of arrival at the office: December 4, 1912

“Registration date: December 9, 1912

“To the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

“This is a response to the letter dated 2 December 1912 and numbered 1249/25475 from the General Directorate of Political Affairs.

“The Bombay Consulate was requested to procure and send a few copies of the books on Mahdiism published by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad from the Qadian Town of Punjab.

“This is an order of the Undersecretariat.”13

This acquisition of Ahmadiyya literature seems to have run deep into the following year. It seems that books were acquired directly from Qadian, as the letter below suggests the arrival of copies of The Review of Religions along with a letter from the then editor, Maulvi Muhammad Ali:

“The exalted Chief Secretary of His Majesty

“Ref: 124

“A person named Muhammad Ali, who wrote the book “Risalah al-adyan” in Punjab, sent us the book “Ta‘lîm-i İslâm” written by Mirza Ghulam Ahmed Khan, along with a letter. The letter and the book were sent to the Ministry of Education for review. To command belongs to him who commands all.

“29 July 1913

“Chief Secretary to His Imperial Majesty”14

The Grand Vizier, or the Ottoman Sultan’s chief secretary or prime minister, saw the book of Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas as an important one and forwarded it to the Ministry of Education:

“Grand Vizier’s Office

“Branch 2

“Ref: 134

“Date: July 30, 1913

“To the Ministry of Education

“We received a letter signed by Muhammad Ali, the author of the “Risalah al-adyan”, stating that Mirza Ghulam Ahmed Khan’s book “Ta‘lîm-i İslâm” was sent to the Grand Vizier’s Office. This may be an important book. The exalted Chief Secretary of His Majesty ordered the book to be sent to the Ministry of Education. The aforementioned book has been sent to your ministry.”15

The books of Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas then went around from department to department: assessing the cost of acquiring them; then sent to the accounts department; and then to the directorate of document registration on 16 September 1913 – a year on from when the entourage was headed to Hijaz.16

All this happened in the time of Sultan Mehmet V (r. 1909-1918). Had it been the time of his predecessor Sultan Abdul Hamid II (r. 1876-1909), Ahmadiyyat would not have been so unknown to the powerhouse of Porte Sublime. Abdul Hamid II had not only known Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas, the founder, but had also sent his emissary Hüseyin Kâmi to Qadian, albeit in vain, to support the crumbling Ottoman caliphate through some form of collaboration.17

Ahmadiyya contribution to colonial Hajj

Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra performed the Hajj in 1912, at a time when the British Indian government grappled with the issue surrounding Indian Muslim pilgrims as one of its most challenging problems.

He returned to India on 6 January 1913 and busied himself with preparing to launch an Urdu language weekly from Qadian, which he named Al Fazl (lit. the blessing). With its first issue coming out on 19 June 1913, he was the proprietor and editor and remained so until he was elected caliph of the Ahmadiyya community in less than a year of the launch.

The Al Fazl soon became the flagship Urdu language publication of the Ahmadiyya community, circulating across the length and breadth of India. Newspaper summaries sent regularly to London by the Indian government carried summaries of various news and editorial columns of Al Fazl. Regular reports on the political climate of the Punjab would assess and convey the inclination of Al Fazl alongside other vernacular papers.

The very first issue of Al Fazl carried an announcement titled “A new arrangement for Hajj pilgrims” (hajion ke liye naya intizam) stating that a detailed discussion around the problems of hajis (pilgrims) would start from the next issue.18

The second issue of Al Fazl, a week into its launch, carried a three-part series of editorials titled gornmint aur hujjaj, meaning “The Government and Hajj pilgrims”.

Before looking into the Ahmadiyya contribution to the British-Indian issues around Hajj, it is important to know and understand the debate that surrounded the issue.

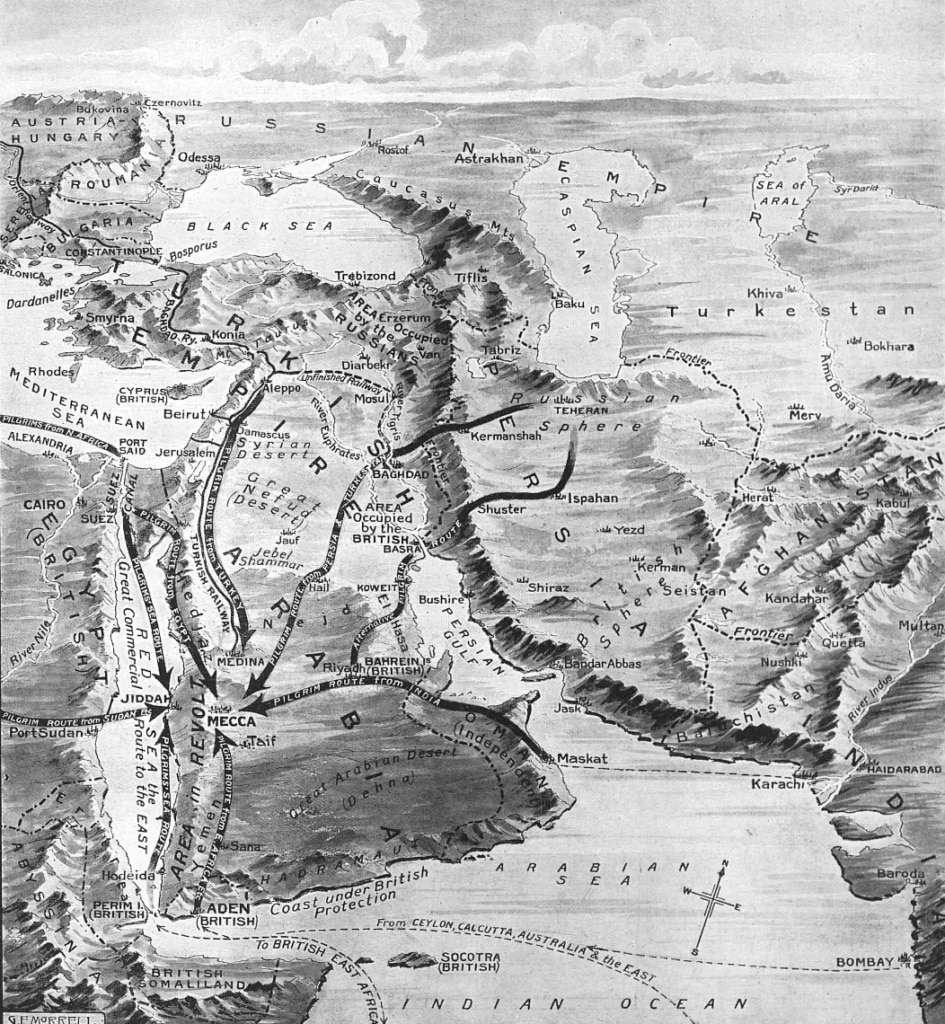

By the turn of the 20th century, the British had incorporated a vast expanse of the Muslim world into their colonial fold. From India to a number of Muslim countries in Africa were either British colonies or functioned under British suzerainty. The British Raj had thus become the greatest “Muslim empire” in that a vast majority of the world Muslim population were its subjects.

At a time when the Ottomans boasted their status of the only Muslim empire, the British Empire contesting in the same area came as a bitter pill to swallow – a cherry on the cake already contaminated with geopolitical conflicts.

The Ottomans saw the British, and rightly so, as a threat to their territories – more so since the British had gained control of Cyprus, Egypt, Kuwait and Aden and the Sinai Peninsula in the late 19th and early 20th century. This had turned Sultan Abdul Hamid II into, as John Slight rightly calls him, an Anglophobe – a tendency that the Porte Sublime inherited and lived with it to the end, until Britain and its allies finally dismantled the Ottoman Empire by 1924.19

The Indian hajis being British subjects travelling to the Ottoman controlled Arabia, and that too amid strained Anglo-Ottoman relations, was a constant pain in the neck for the Ottomans. However, both empires were bent on facilitating the Hajj for their Muslim subjects to keep Muslim loyalties under their belts.

The Ottomans were not only sceptical of the British Raj but also of their Muslim subjects. Despite the trend of Indian-Muslim inclination towards the Ottomans (later developing into the likes of Khilafat Movement), a vast majority of Muslim circles remained expressly loyal to their British colonial masters – a fact that became vividly apparent when Indian Muslims expressed their loyalties to the British Crown and not the Ottoman Empire in World War I.20

Indian-Muslim loyalty remained a precious commodity for both the contesting empires, leading both to capitalise on it for their own political benefits – the British to be seen as sympathetic towards their Muslim subjects, the Ottomans to legitimise their role of khadim-i-harmain sharifain (lit. servants of the two holy shrines).

Ottoman authorities were suspicious of Indian Muslims settling in the Hijaz yet maintaining their status as British subjects, which kept them under British protection, should the Ottomans not be favourable.

Another suspicion giving Ottoman authorities sleepless nights was the British interest in Arab separatism through establishing a new caliphate.21 If a caliphate in Arabia were to be established, parallel to that of the Ottomans, it could mean a fatal blow to the unique jewel in the Ottoman crown. This ought to be kept in mind when we return to the enquiries and prosecution attempts against the Ahmadiyya pilgrims in 1912.

The question of destitute pilgrims

Favourable circumstances extended by the British government towards its Muslim citizens to perform Hajj kindled in the heart of every other Muslim to set out to perform this ritual, ignoring that affordability and feasibility were two main conditions set by Islam.

The British-Indian government would spend huge funds to repatriate the hajis that had travelled to Hijaz with a one-way ticket. The Bombay Hajj department spent Rs 25,000 to repatriate 4,000 hajis in 1912.22

While such destitute hajis – as they were termed in official correspondence – awaited repatriation at the port of Jeddah, some were found begging in streets for food or/and money.23 This was frowned upon by not only the Ottoman authorities, but also by the British-Indian vice-consuls in Jeddah responsible for managing the affairs of hajis. The Ottomans highlighted and propagated it as a failure of the British administration of Hajj, the Jeddah-based Indian officials saw it as a dent in the imperial prestige of the Raj.24

These destitute hajis would remain stranded in Jeddah for months and beg on the streets to arrange subsistence, become seriously ill, and fall prey to the ruthless outbreaks of cholera or other epidemics; some would starve to death as they waited for repatriation arrangements by the government back home – a process that could take months.25

The solution to this issue of destitute pilgrims remained stuck in the neck of the British-Indian government for many decades that led up to World War I, only to be resolved when the Hajj resumed, albeit partially, on the other side of the war.

Over the decades, numerous Hajj committees were established, Muslim philanthropists were involved, the general Muslim opinion was sought, and influential Muslim leaders were taken on board. However, a simple solution could not be reached: making the Hajj journey conditional on purchasing return tickets beforehand. 26

The main opposition to any such proposal by the government came from Muslims who saw it as a direct intervention in religious freedom and hindering an Islamic ritual.27 Ironic it is that Muslim circles opposed a suggestion by the government even though the suggestion was more in line with Islamic teachings: one should only intend to go to Hajj if they can afford and if circumstances are favourable and feasible. Such a sentiment acted as a repellent for the British, who did not want to lose Muslim loyalty by being seen as standing between them and their religious duties – a politically pragmatic measure more than one of altruism or sympathy.

The Hajj of 1912 is said to be a watershed moment for the question of destitute pilgrims, where there were over one thousand Indians in “abject misery” – as the Jeddah vice-consuls reported – many of whom had succumbed to the situation and died.28

The question of destitute pilgrims would punctuate the Indian press around the Hajj season every year, and Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra must be very well aware of it. Added to this knowledge was now his first-hand, eyewitness observation.

This newfound insight resulted in the editorials that spanned the Al Fazl issues of 25 June, 2 July and 16 July 1913.

Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra made these observations, and his subsequent proposals regarding destitute hajis, at a time when he was under surveillance by Ottoman authorities and prosecution was only a hair’s breadth away.

The Ahmadiyya proposals

Hajj remained an enterprise managed mostly by Muslim personnel hired by the British-Indian government.29 It seems that the government had the Hyderabad model in mind, where the Nizam’s administration facilitated the Hajj travel for pilgrims, even enabling its underprivileged (and Islamically unqualifying) subjects to undertake the journey. Hyderabad too had to arrange repatriation for certain destitute pilgrims, but it was done more diligently through the availability of huge funds reserved for Hajj, and an act of philanthropy by the Nizam.30

Since the government did not involve itself in Hyderabad’s Hajj affairs, Bombay remained the main Indian port for Hajj departures/arrivals throughout the British Raj in India. As a major port of this scale, it attracted Muslims not only from all over India but from other neighbouring regions like Iran, China, and even some Central Asian states.31

With a “catchment area” of such vast transnational scale, any competition with Hyderabad was not viable. Yet, the British government, for political goals we have discussed above, continued to allow destitute pilgrims-to-be aboard and later repatriated thousands of them after the Hajj.

Following the Hyderabad model, the British Hajj department had a Muslims-only recruitment policy – both onshore in Bombay and offshore in Jeddah. This arrangement must have helped with not having to employ interpreters where native Muslim staff dealt with native hajis.

While the government’s Hajj department and the many Hajj committees woven around the enterprise hired Muslim personnel, the network of Hajj brokers across India was of an all-Muslim nature, too. These businesses, masked in piety but purely commercial in spirit, were known to the government’s agencies as dishonest and fraudulent.32

Their agents would travel town to town, village to village and persuade poor people to travel to Hajj, telling them the journey and its paraphernalia being too costly was only a false story and should not be believed. They would even sell them packages for small amounts of money and hand them a one-way ticket, leaving the unlettered Muslim masses joyous to see their dream of a lifetime come true.33

With the destitute pilgrims’ issue a constant pain in the neck of the British government, advice and consultation too had to be sought from anjumans: scholars and influential individuals who, for obvious reasons, had to be Muslim.

One such consultative committee was the Bombay Hajj Committee founded in 1908 and consisting of elite Muslims like merchants with interest in India-Hijaz trade, hostel owners in the Hijaz, a manager of the Persian Gulf and Steam Navigation Company etc.34 The committee had to be abolished when the government observed next to no productivity over years, yet active misuse of the committee’s platform to bolster personal/commercial interests.35

Maulana Shaukat Ali established an Anjuman-e-Khuddam-e-Ka‘bah (lit. servants of the Ka‘bah association), with various branches across India in an attempt to alleviate the problems of Indian hajis. With his loyalties for the Ottomans coming to the surface, the anjuman was abolished by the government.36

Influential Muslim individuals like Maulvi Rafiuddin Ahmed, from Bombay’s Muslim community, wrote to the Bombay police and, while praising the government for its sympathies towards its Muslim citizens, condemned the return ticket proposal and saw the restriction as coercion in religious affairs.37

It was in this atmosphere that the government’s proposals emerged, and the subsequent response in the form of editorials by Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra.

The Bombay government intended to impose several conditions for prospective hajis, one of which was for hajis to purchase a return-ticket and not a single ticket to Jeddah. Muslim circles had seen these reforms as offending the Muslim religious sentiment and a breach of freedom of faith.38

He identified the root cause of the problem to be in the Muslim misunderstanding and misconception about the Islamic injunction of Hajj. He noted that while Hajj is obligatory for every adult Muslim at least once in their lifetime, it has certain prerequisites that need to be met before one sets off for the ritual: being capable in terms of health and wealth; having discharged all familial duties; having ensured their own sustenance during the journey and that of their household members behind etc.

A pilgrim classed as a destitute one, or a “pauper pilgrim” as sometimes referred to in official documentation, was obviously ignoring the Hajj criteria set by none else but Islam. Even worse, Muslim intelligentsia did not approve of the government introducing measures like imposing a return-ticket purchase beforehand.

Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra highlighted this sad fact and urged Muslims to cooperate with the government where its demands were reasonable; and if the case was otherwise, offering the best advice rather than only throwing spanners in the works.39

Bombay government records on Hajj hold ample evidence that Muslim influential figures stood in the way of the government’s attempts at resolving the issue. We have seen certain instances above, and more can be seen in various works on this subject.40

In the second part of the series, Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra raised the question of whether the issue of destitute pilgrims is even real or not. He answered in the affirmative and said that in doing so, he relied on his own observations from his visit to the Hijaz the previous year.

He saw that the agents were culprits in presenting to the innocent masses a false picture of expenses that incur on the entire journey to and from Hijaz, only to make some financial gain out of them by selling one-way tickets to Jeddah.

He listed the difficulties that pilgrims faced when they set out with little and insufficient resources – the journey from Jeddah to Mecca and then to Medina costs more that most people imagined; accommodation in Mecca being quite costly; compromised accommodation resulting in pilgrims becoming prone to catching diseases; food being a significant expense head which becomes unaffordable.41

In the third and final part of the series, Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra laid out his suggestions:

- The condition of purchasing a return ticket should most definitely be imposed.

- The government, or its agents and representatives in Hajj committees, should raise awareness about the true requirements of Islam regarding Hajj; yet no one should have the authority to stop anyone from undertaking this journey.

- The government should not let any shipping company monopolise the Hajj journey as that leaves no choice for hajis but to travel in destitute circumstances.

- The government should invite tenders, a year in advance of finalising any deals, so that the best travel deals could come to the surface before contracts were finalised.

- The government should ensure that shipping companies start sailing straight after Hajj so that hajis did not have to wait in Jeddah for days or weeks at a time when they had run out of funds. He gave the example of how the Dutch government had made such arrangements for its Java pilgrims who left the port of Jeddah straight after and did not suffer the perils of an overstay.

- Ships should be in a sound condition that do not breakdown before setting off or during the voyage, as they most often did.

- Vessels that could travel faster could save time and transport more hajis back home.

- Increasing the number of vessels departing from Jeddah would allow room for hajis to move and walk around. The current state was such that they were crowded and were prone to catching illnesses from each other.

- A committee of influential Muslims be formed that can liaise between the government and the general masses in regard to Hajj-related problems.

- If a haji dies while in Hijaz or does not turn up to claim his return journey, the cost of this ticket should Be donated to one of such Hajj committees, rather than being handed over to the shipping company, so that the money can be used for the welfare of future pilgrims.

- One of the officers of such committees should always remain in Jeddah where he can liaise between the pilgrims and the council in Jeddah, because most of the destitute pilgrims do not even find the courage to set foot inside the consulate.

- Such committees should be able to examine the situation on the vessels to ensure the well-being of the pilgrims aboard.

All these proposals were documented and sent by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community to Lord Hardinge, the Viceroy of India, to which an acknowledgment of receipt was received from his office, along with the note that the proposals had been forwarded to the relevant department.42

The discussion went on for almost a year, and owing to the pressure from Muslim circles on the government and the government’s diplomacy in terms of the Hajj question, the return ticket proposal was dropped, and the issue of destitute pilgrims remained as it was.

The problem, chronic as it was, surfaced again in 1914 with the same concerns and came to the same end, i.e. no end.

Al Fazl reproduced the same proposals that it had sent the previous year and reinstated that while the government should not take a backseat approach and leave such pressing issues at the disposal of its agents, Muslims should also refrain from the habitual approach of condemning the government’s proposals without sound reason.

Al Fazl reiterated that return tickets should be made compulsory. Also, the government’s undue reluctance in taking necessary measures only for the fear of Muslim reaction is counterproductive in serious and damaging ways.

Historians today look back and see the Muslim intelligentsia standing in the way of any progress regarding the destitute pilgrim problem. John Slight and Radhika Singha, two historians specialising in colonial Hajj, have given ample evidence to support this notion; I quote Singha’s observation as representative:

“Enlightened Muslims were invited to declare that this was a violation of the Islamic injunction that the pilgrim must ‘be able’ to perform the Hajj. Yet for reasons related to geo-politics, commerce and legitimacy of rule, the Government of India too could not entirely subsume ‘the problem of the pauper pilgrim’ […]. Sections of the Muslim intelligentsia also refused to let it do so.”43

This core problem was exactly what Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra had identified and called upon influential Muslims, as well as the government, to nip in the bud.

Then struck World War I and all transnational travel, including Hajj, was hugely disrupted. Recovering from the devastation of the war, Britain was left to reconsider all its policies, with foreign policy being top of the list.

Finally, in 1925, an amendment was made to the Indian Merchant Shipping Act, which, linking the pilgrim permit to the ship ticket, automatically ensured that underprivileged pilgrims bore the entire cost of their journey to and from Hijaz.44

Al Fazl celebrated this legislation by running another series of articles from March 1925,45 showing appreciation that the amendment had finally been made in line with the proposals of Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra.

Section 208-A of the act read:

“Conditions for securing return passages for pilgrims:

“No pilgrim shall be received on board any pilgrim ship at any port or place in India for conveyance in the lowest class available on the ship, unless he

(a) is in possession of a return ticket, or

(b) has deposited with the prescribed person such sum for the purpose of defraying the cost of a return ticket as the Central Government may specify by notification in the Official Gazette.”

Section 208-B required ship owners, i.e. the beneficiaries of return-tickets, to provide pilgrims with “food and water, on the scale and of the quality prescribed, free of further charge, throughout the voyage.”46

Section 208-C made it mandatory for the shipping companies to ensure that any pilgrim who has to/is made to disembark without completing the journey “shall be entitled to the refund of any passage-money which he may have paid, and of any deposit which he may have made under Section 208-A”.47

The same section ensured that “in the case of a pilgrim’s death in the Hedjaz or on the voyage thereto, any person nominated by him in this behalf in writing in the prescribed manner, or, if no person has been so nominated, his legal representative, shall be entitled to a refund of any deposit made by such pilgrim under Section 208-A, or if such pilgrim was in possession of a return ticket, to a refund of half the passage-money paid by such pilgrim.”48

Section 209-B asked the shipping companies to declare the entire itinerary, the number of pilgrims allowed, tonnage and age of the ship, the price of each class, and the probable date of arrival at Jeddah.49 The same section of the act imposed strict scrutiny on “master, owner or agent” of the shipping company to not advertise or promise any false particulars related to the journey.

This amendment was the first serious attempt towards securing the rights of Indian pilgrims at home and while on Ottoman soil.

Conclusion

The mainstream Muslims always saw members of the Ahmadiyya community as heretics, and fatwas had been issued declaring Ahmadiyyat out of the pale of Islam and hence not eligible to enter the environs of the holy shrines of Mecca and Medina.

This discrimination saw new heights with the constitution of Pakistan declaring Ahmadis not Muslim and compelling them to state their religion as Ahmadi in order to be identified as such and prohibited from Hajj, or even performing any Islamic ritual in any part of the Muslim world.

While the constitutional restrictions are relatively new, we have seen above that the discrimination against the Ahmadiyya was institutionalised a hundred years ago when the Ottomans ruled Arabia.

The Ottomans, as we have seen, viewed the British with a sceptical eye not only for their political encroachments but also for their exploitation of religious symbols like the caliphate.

We know, just as much as the Ottomans did, that establishing a parallel caliphate in Hijaz remained on the cards of Britain’s tactical diplomacy in the early decades of the 20th century; what more could Sherif Hussein of Mecca dream of, and what more did the British want to deepen the cracks in the Muslim world.

The panic in Porte Sublime, ignited by the reports on the “Qadiani” pilgrims, seems more to be out of political concerns than mere piety. The Ahmadiyya had established a caliphate after the demise of their founder in 1908.

By 1912, when the Ottomans sounded the alarm bells, the Ahmadiyya caliphate had started sending missionaries abroad, with Khwaja Kamaluddin reaching the English shores in September 1912, just before the entourage of the Ahmadiyya set foot in Hijaz.

Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra and his entourage might not have known about the correspondence mentioned for the first time in this article, but they had received face to face death threats, were harassed and called names, and their accommodation raided for prosecution purposes, albeit a near miss by only a day – all this their firsthand experience.

Despite knowing quite clearly that the doors to Hajj might eventually shut on the Ahmadiyya, Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra continued to strive for the wellbeing of his coreligionist hajis – coreligionists who had disowned him and his community.

I conclude with a striking statement that Al Fazl made when the Jeddah-based Indian-Muslim vice-consuls raised the issue of destitute pilgrims with the British government as a disgrace to “imperial prestige”:

“It would have been more appropriate if the issue was raised in the name of Islam’s prestige than the prestige of British government. Islam has made the Hajj obligatory only for those who can bear its expense […]. Destitute pilgrims begging in the streets and creating nuisance are a disgrace to Islam, and anything done for them would first be a service to Islam and then to any government.”50

Endnotes

1. Badr, Qadian, 12 December 1912

2. Ibid., 7-14 January 1914

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Al Hakam, Qadian, 7-14 January 1913

7. Al Fazl, Qadian, 7 March 1921

8. Ottoman Archives, DH.SYS.31.8.3

9. Ibid., DH.SYS.31.8.2

10. Ottoman Archives, DH.SYS.31.10.1.1

11. Ibid., DH.SYS.31.10.2.1

12. Ottoman Archives, DH.SYS.31.10.3.1

13. Ottoman Archives, DH.SYS.31.8.1.1

14. Ottoman Archives, i.MBH.12.99.2.1

15. Ottoman Archives, BEO.4201.315060.1.1

16. Ibid., DH.SYS31.8.4

17. Asif M Basit, The British, the Ottoman and the Heavenly – A tale of three empires: An account of Hüseyin Kâmi’s visit to the Promised Messiah, www.alhakam.org, 19 March 2021

18. Al Fazl, Qadian, 19 June 1913

19. See Azmi Ozcan, Pan-Islamism: Indian Muslims, the Ottomans and Britain (1877-1924), in The Ottoman Empire and its Heritage, Vol. 12, 1997

20. The War: Muslim Feeling, Expressions of Loyalty, File IOR/4265/1914, L/PS/10/519, India Office Records, British Library

21. IOR/L/PS/18/B222, secret file titled: Correspondence with the Grand Sherif of Mecca, India Office Records, British Library (being the secret correspondence between JMC Cheetham, Acting High Commissioner at Cairo, and Hussein ibn Ali, the Sherif of Mecca

22. National Archives of India (NAI), Foreign Department, Internal-B, 20 December 1912, 349,352

23. NAI, Foreign Department, Internal-B, August 1913, Government of Bombay to Government of India, 15 March 1912, No 349-352

24. Maharashtra State Archives (MSA), File 768, Vol. 140, Bombay Government Resolution, 11 December 1913, General Department

25. NAI, Foreign Department, Internal-B, No 349,352, Hajj Report 1911-1912 by Dr S Abdurrahman, Vice-Consul Jeddah

26. Responses from Muslim leaders and influential figures from Bhopal, Ajmer, Quetta, Gwalior, Indore, Punjab etc in NAI, Foreign Department, Internal-B, September 1907, NO 111-140

27. Ibid., Rai Itbar-ul-Mulk Sayyid Muhammad Iftikhar Husein Muztir, Superintendent Court of Wards, Gwalior State, 28 February 1906

28. MSA, Commissioner of Police, Bombay to Secretary, Government of Bombay, 24 July 1911, General Department, 1911, File 62A

29. John Slight, The British Empire and the Hajj: 1865-1956

30. Eric Lewis Beverley, Hyderabad, British India, and the World: Muslim Networks and Minor Sovereignty, c. 1850-1950, Cambridge University Press, 2015

31. Nile Green, Bombay Islam: The Religious Economy of the West Indian Ocean, 1840-1915, Cambridge University Press,

32. MSA, Report on Pilgrim Season Ending 30 November 1909, General Department, 1910, File 615, Vol. 134

33. See Amir Ahmad Alawi, Journey to the Holy Land: A Pilgrim’s Diary, translation by Mushirul Hasan & Farkhanda Jalil, Oxford University Press, 2009

34. MSA, Haj Committee Rules and Regulations, Government Resolution No 5497, 5 September 1908, General Department, File 1088, Vol 143

35. MSA, Resolution on Re-appointment of Hajj Committee Members, 4 October 1912, General Department 1912, File 1368, Vol 128

36. David Page, Prelude to Partition: The Indian Muslims and the Imperial System of Control, p 24, OUP, Delhi, 1982

37. MSA, Rafiuddin Ahmed to Commissioner of Police, Bombay, 29 January 1906, General Department 1912, File 768, Vol 132

38. Mark Harrison, Quarantine, pilgrimage, and colonial trade: India 1866-1900, in Indian Economic and Social History Review, Vol. 29, No. 2, 1994

39. Al Fazl, 25 June 1913

40. See Radhika Singha, Passport, ticket, and India-rubber stamp: ‘The problem of the pauper pilgrim’ in colonial India c 1882-1925

41. Ibid.

42. Al Fazl, 19 June 1914

43. Radhika Singha, Passport, ticket, and India-rubber stamp: ‘The problem of the pauper pilgrim’ in colonial India c 1882-1925, p 50

44. Indian Merchant Shipping Act of 1923, amended by Act XI, 1925

45. Al Fazl Qadian, 28 and 31 March 1925

46. Shipping Act XI 1925

47. Ibid.

48. Ibid.

49. Ibid.

50. Al Fazl, 31 March 1925