Asif M Basit, Ahmadiyya ARC

The question of how the British entered and gained a foothold in the subcontinent to turn it into a British colony is a lengthy story, which need not be told here. However, it ought to be kept in mind that the British were not able to reign over India peacefully from the start of the mutiny in 1857 until the partition and freedom of India.

The Geo-political situation at the time of the Promised Messiah

The 18th and 19th centuries were a time of great conflicts. All major powers were occupied in establishing colonies and expanding their territories. The British had gained dominance over the subcontinent by defeating the French. Although a Muslim empire had ceased to exist in the Indian subcontinent, its bygone legacy had left its remnants in certain pockets; the resistance movement of Tipu Sultan being the most significant one.

The Russian empire had long desired to break in to the Central-Asian states – then part of the Ottoman Empire – as that could be a key move to their expansion in all major directions.

The Ottoman Empire was, geo-politically speaking, like a buffer between the east and the west that could play a key role in the potential expansion of other empires; equally so in containing and resisting their advances. India and the Ottoman Empire were neighbours and the latter had always had its eyes set on the former. However, the British conquest of India had dampened such Ottoman ambitions.

Before delving deeper in our topic, it must be noted that the Ottoman Empire was engulfed by major powers: British-India to the east, Russia to the north, Germany to the west and North Africa, colonised by the French, to the south.

Such was the scene on the global political theatre where the above-mentioned powers were major actors.

British-Ottoman Alliance

The East-India Company – a forerunner of the British Raj – undertook the role of imperialising India through commerce. This resulted in a backlash by the local rulers, like Tipu Sultan, whose resistance was backed by the French military forces of Napoleon Bonaparte. It is this that resulted in the Anglo-Mysore wars of the 18th century.

Arthur Wellesley – known more commonly as the Duke of Wellington – was at a key position in the British army that fought against the Mysore uprisings.

He was not only well-versed in military tactics but had deep insight in politics. He sought the help of the Ottoman-Sultan Selim III to bring about his influence as Sultan-Caliph of the greatest Muslim empire and convince Tipu Sultan to refrain from his military conflicts with the British. Persuaded by Wellesley’s appeal, Sultan Selim III wrote a letter to remind Tipu Sultan of the atrocities inflicted upon the Muslims by the French, advised him to hence abandon their alliance, and cease resisting the British. Sultan Selim III went on to declare that not showing resistance towards the British was a religious obligation. (Britain, India and the Turkish Empire, by Ram Lakhan Shukla, People’s Publishing House, New Delhi, 1973)

Why it was important for the Ottoman to maintain friendly terms with the British calls for a detailed look at the political scenario of that time. Briefly put, Central-Asia was candy to the eyes of the Russian empire which happened to be under Ottoman control. Marching into the Central-Asian region could potentially open up ways for Russian advancement towards not only the Ottoman mainland but towards India as well. Curbing Russian advances towards the region worked as a common interest for the Ottomans and the British, resulting in friendly ties.

Sultan Selim III’s favour in suppressing Tipu’s resistance had to be reciprocated by the British.

British Empire and the Indian-Muslims

Very well-known is the fact that what seems in politics a friendly gesture, is usually a vested interest. It was in the interest of the British to curb the Russians from taking control over Central-Asia which could allow the Russians to march into Afghanistan and, subsequently, its neighbouring India.

The actual impetus behind the British-Ottoman alliance was that the Ottomans could not afford to lose a vast part of their Empire to Russia while the British did not want to surrender India. This interest worked as the main ingredient for the alliance between the British and the Ottomans.

Another factor was the British knowledge of how the Ottoman-Sultan had been able to influence Tipu Sultan for being his co-religionist and the emperor of the only remaining Islamic empire. It was this position of the Ottoman-Sultan that the Indian-Muslims too held him in high esteem; he was not only a symbol of the lost glory of Muslim majesty, but also the custodian of the two holy shrines in Arabia. This combination of political glory and emotional attachment was something that could not be detached from the collective psyche of the Indian-Muslims and the British never failed to bear this connection in mind. It was this understanding that called for the British to acquire Indian-Muslim sympathies. (“Empire and Hajj: Pilgrims, Plagues, and Pan-Islamism”, by Michael Christopher Low, in International Journal for Middle Eastern Studies, No 40, 2008)

The Crimean War (1853-1856) was a defeat for the Russians and a victory for the British-Ottoman alliance. Absolute support shown by the British in this war had struck a chord of sympathy for the British in the Indian-Muslims, who now saw the British as a friend of the Sultan and, hence, as well-wishers of Islam. (RL Shukla)

While the war was being fought, Lord Dalhousie felt a growing love and affection being embedded within the Indian-Muslims for the British, although he never forgot the actual purpose behind the British moves; the vested motives discussed above. (Private Letters of the Marquis of Dalhousie, by JGA Baird, William Blackwood & Sons, London, 1910)

“Help your brethren” was the slogan that enabled the British to get Muslims enrolled in the Crimean War. The overwhelming response shown by the Indian-Muslims was proof that they had accepted the British as the well-wishers of Muslim interests. (Relations of the Ottoman Empire with the Indian Rulers, by Shamshad Ali, PhD Thesis Aligarh Muslim University, 1988)

As the Crimean War came to its end in 1856, the clouds of mutiny loomed the Indian horizon. The British looked towards the Ottoman Sultan to once again come to help. Obliged by the British support against the Russians in the Crimean episode, the Ottoman Sultan issued an imperial decree to the Indian-Muslims to abstain from any resistance against the British; failing to comply was declared a contempt to the Sultan, their “Caliph”. The then Ottoman-Sultan, Abdulmejid I, in trying to ignite sympathy for the British, reminded the Indian-Muslims of how the British had served as good friends in the Crimean War. (National Archives of India, Federal Department, Secret Consultation, no 298)

Going an extra mile, Sultan Abdelmejid I donated a sum of 1,000 pounds for the Mutiny Relief Fund setup by the British government in India. (National Archives London, PRO, FO, 78/1271)

The British, with the Ottoman Sultan on their side, managed to nullify the fatwas of Jihad against the British,which had been published in the Urdu akhbar (newspaper), Delhi, on 26 July 1857. This decree had 34 Indian-Muslim scholars, including the likes of Fazl-i-Haq, as signatories. Similarly, copies of the fatwa were also published by several other notable newspapers like Sadiq-ul-Akhbar, Delhi, etc.

Before moving on, we would like our readers to note that the prohibition of Jihad against the British first came from none else but the Ottoman Sultan – known to the Muslim world as their Caliph – obedience to whom was obligatory.

Sultan Abdulaziz was the first Ottoman Sultan to tour England in 1867 and that too on a special invitation by Queen Victoria. The British Government in London acknowledged his tour as a state visit. All expenses of entertaining this state visit were drawn from the budget of the India Office. The reason given for doing so, as official correspondence of London and India shows, was to show the Indian-Muslims how dear the Ottomans were to the British Empire. (The Times and Life of Queen Victoria, Cassell and Co, London, 1901; The Times, London, 13-24 July, 1867; Friend of India, 1 August, 1867)

Upon return of the Ottoman Sultan from London, Russian advancements in the region had become an even greater threat and seemed inevitable. Given the situation, a strong alliance between the two empires, British and the Ottoman, was the only way forward. Thus, it was in the British interest to enlist Muslim soldiers into the British-Indian army. Such motives could not materialise unless the British Government adopted a gentle approach with the Indian-Muslims. The British government, thus, set out a policy to showcase their solidarity with the Sultan as protectors of Muslim interests.

Ali Pasha, the prime minister of the Ottoman Empire, wrote a letter addressing the Indian-Muslims to express his sincere congratulations to them for living under the British rule that stood for religious freedom. He also expressed that the Ottoman Sultan-Caliph would never accept any action against the British government. (NAI, FD, Secret H, Vol 1869, no 111, British ambassador at Constantinople to Foreign Secretary, 9 October 1869)

On the other hand, influential Muslims, such as Sir Syed Ahmad Khan would speak highly of the Ottomans to attach the Indian-Muslim imagination to the Sultan. Modern Muslim historians refer to Sir Syed as a great associate of the Ottoman Sultan, even mentioning his endearments to make the Turkish fez fashionable in Aligarh. But the fact of the matter is that Sir Syed Ahmad Khan was so compliant to the British policy that he left his own opinion quite flexible. Furthermore, whenever British policy clashed with Ottoman interests, Sir Syed would either remain silent or condemn the policy of the latter. (Ittehad Bain al-Muslimin, by Khalid Amin, Research Journal Tahsil, July 2018)

Consuls of the Ottoman Empire in India

The friendly relations between the British and the Ottomans took a new turn when the Turkish consuls were allowed to be appointed in India. In 1849 the Ottoman sent their first consuls to Calcutta and Mumbai. Their purpose, according to the India Office Records and the Ottoman Archives in Istanbul, was to execute the affairs of the merchants and Muslims travelling to the Ottoman lands. (Pan-Islamism: Indian Muslims, the Ottomans and Britain, by Azmi Ozcan, Brill, 1997)

Pilgrims traveling from India began benefiting from the consulates, consequently creating a surge of Indian-Muslims travelling to the Ottoman territories by land and sea. Indian-Muslims started to develop a natural tendency to the Ottomans on account of being the custodians of Mecca and Medina. They also felt that this was the last remnant of Islam’s former glory. Subsequently, it was generations of the collective psyche that played an important role in developing close relations with the Ottoman.

However, the foundation of consulates and an increase of travels to the Ottoman Empire led to new fears within the British camp. (Azmi Ozcan)

Indian-Muslim interest in Pan-Islamism

The Indian-Muslims and the Ottomans had developed a deep connection by 1870; initially inculcated by the British themselves, and discussed above. Other causes were the status of the Ottomans as that of a Muslim Empire, the leadership of a “Caliph”, the potential revival of a united Muslim Empire and liberation from an “infidel” ruler. (Pan-Islamism in British-Indian Politics, by Naeem Qureshi, Brill, 1999)

The Ottoman Sultan was well aware that Muslim citizens outside the Ottoman territories regarded him as their “Khalifa” and considered it obligatory – at least in theory – to heed his command. For the Sultan, the Muslim population was a political pool that he could use to his advantage.

The British began to cautiously observe this romance-in-the-making and kept the Ottoman consuls under strict surveillance. Indian-Muslims traveling to the Ottoman territories too were kept under surveillance, including detailed reports provided by the British consuls based in Ottoman lands. (“Azmi Ozcan; Contested Subjects”, by Faiz Ahmed, in Journal of the Ottoman and Turkish Studies Association, no 3, 2016)

In 1880, a decade later, the Ottomans, through their pan-Islamic propaganda, had succeeded in winning the political sympathies of Indian-Muslims. They had realised that Britain’s alliance was purely political and not likely to last any longer than her vested interests. On the other hand, Indian-Muslim religio-political sentiments had further strengthened with the Ottoman sultanate.

Influential Muslims began regular attendance with the Ottoman Sultanate during this decade. These Muslims set about to pull their weight for Pan-Islamism in line with the Ottoman agenda. In May 1880, the Ottoman launched an Urdu newspaper, Paik-i-Islam and painstakingly circulated it in Indian-Muslim circles, especially in the princely states; Muslims as leaders of such states were seen as more promising and potentially easily lured “converts”. (“A Study of the Attempts for Indo-Turkish Collaboration against the British”, Journal of International History)

Hasib Efendi, an Ottoman ambassador, was stationed in Mumbai during the entire decade of 1870s. He was closely monitored as he continuously popped up on the British radar for stepping outside his remit to mingle with local Muslims. Secret reports would carry detailed surveillance reports of him having moved his residence closer to Muslim neighbourhoods, offering Jumuah prayers in local mosques and having the sermons read in the name of the Ottoman Sultan-Caliph. (Azmi Ozcan; Faiz Ahmed)

The Sultan saw Hasib Efendi’s efforts at fruitful in strengthening the Indian-Muslim allegiance to the Ottomans. The Ottoman Empire, happy with these results, went on to request the British-Indian government to allow more consuls in India. (Azmi Ozcan)

Their repeated requests were repeatedly denied on the grounds that the consuls ought only to restrict themselves to ports where their purpose was being met adequately. Having sensed the actual desire behind further encroachment towards the hinterland, the British continued to decline such requests. (Contested Subjects, by Faiz Ahmed)

The Ottoman sultanate had insisted on permission to establish embassies in Hyderabad (Deccan), Delhi, Lahore, Peshawar and Karachi. Evidently, these were the towns with a majority of Muslims. On the basis of not being port cities, the British rejected the construction of embassies in all towns but Karachi. (NAI, FD/Secret/March 1878/6-63)

Ottoman Consulate in Karachi

The Ottoman consulate in Karachi was inaugurated in early 1890s. It was during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II that the Ottomans began utilising Western means of communication; their aim being to bolster the shaking empire through a pan-Islamic political scheme. Thus, a plethora of newspapers promoting such sentiments mushroomed during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II with Indian-Muslims as their target audience. The British-Indian government, however, did not take long before banning their circulation in India and also proscribing any copies that may have arrived. (RL Shukla)

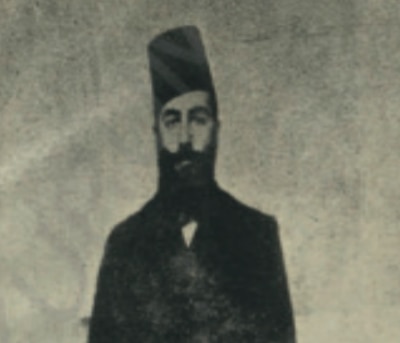

Sultan Abdul Hamid II did not relent and continued to explore various avenues. In 1896, he deployed Hüseyin Kâmi to the Karachi consulate as vice-consul. Upon arrival, Hüseyin Kâmi immediately began touring the subcontinent. He visited the general Muslim public, Muslim societies – or anjumans as they were commonly called – and influential Muslim leaders.

He was more of a propagandist and political activist in the guise of a consul. His tour was nothing more than an effort to shift the Muslim mind-set towards Ottoman loyalty through igniting pan-Islamic sentiment. (Azmi Ozcan and Survey of International Affairs 1925, by AJ Toynbee, Oxford University Press, 1927)

Numerous Muslim anjumans had been established after 1857 for Muslims to voice their own opinions. Most notable was the Anjuman-e-Islamia Lahore, founded through the efforts of Khan Bahadur Barkat Ali in 1866 and out of this anjuman had hatched many more; subsequently playing an important role in shaping Indian-Muslim political ideologies. Its headquarters, the residency of Khan Bahadur Barkat Ali, was in Mochi Darwaza – the heart of the city of Lahore – later shifting their headquarters to Mohammedan Hall in 1988.

Khan Bahadur Barkat Ali’s Anjuman-e-Islamia retained a patriarchal position among all other Muslim societies. (“Role of the Anjumans for the Promotion of Education in Colonial Punjab”, by Maqbul Awan, Bulletin of Education and Research, Vol 41, 2019)

Eventually, when Hüseyin Kâmi’s tour of the Muslim majority areas brought him to Lahore, where he was a guest of Khan Bahadur Barkat Ali, he met the prominent Muslim leaders of Punjab as well as members of Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya, who introduced him to their community. (Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyyat, Vol I, Dost Muhammad Shahid, Rabwah)

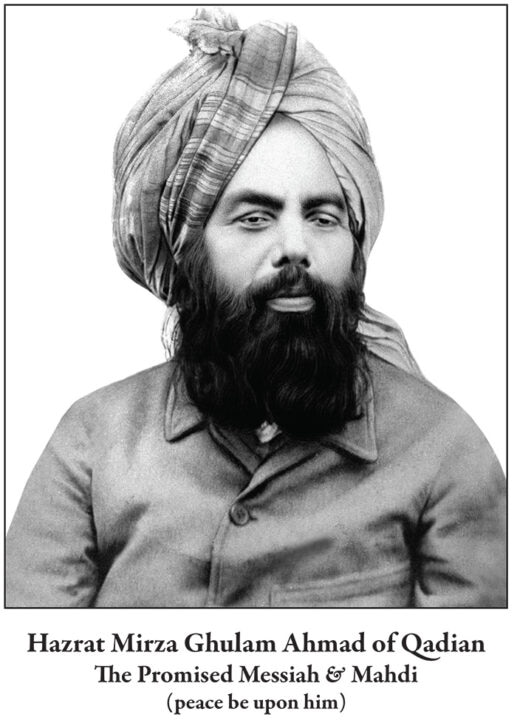

Hüseyin Kâmi’s meeting with the Promised Messiahas

Hüseyin Kâmi arrived at Qadian in late April or early May 1897 (a debate around the date is given under “post scriptum” at the end of this article) to meet the Promised Messiahas). Although the Jamaat’s literature does not specify the purpose of this meeting, his pan-Islamist motives are clearly evident from the details given above.

He was touring the Muslim regions of the subcontinent, all in an attempt to instil sympathy and good-will towards the Ottoman sultan and his empire and, all the while, campaigning for Greco-Turkish war funds.

He had met numerous Muslim anjumans and delegations during his stay in Lahore and had been introduced to the Ahmadiyya Jamaat too. His hosts in Lahore must have informed him that the Ahmadiyya section of Indian-Muslims would not become part of any religious or political movement without express intimation from their leader, Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Qadiani. It must have been the same agenda that made him travel to Qadian and hold this meeting, which we know was held in private.

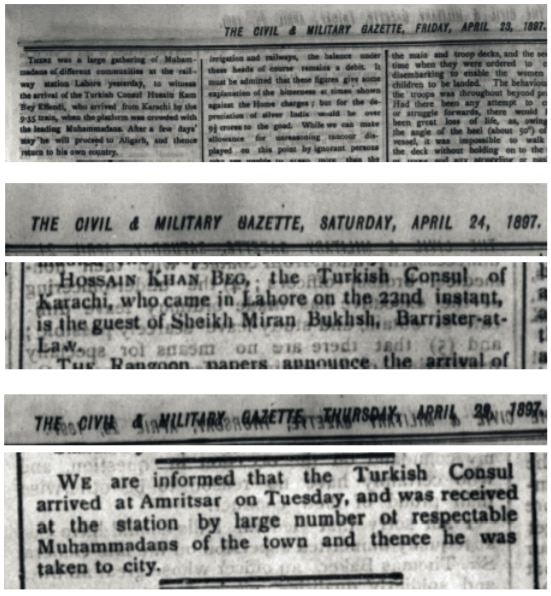

The Civil and Military Gazette published a series of detailed reports on this tour. The edition from 23 April states, “[…] his arrival at Lahore railway station on 22nd April 9.35 in the morning was welcomed by a crowd of Muslims.”

27 April reads: “[…] after reading the Friday prayer in Badshah mosque on the 23rd, Hüseyin Kâmi gave a speech where he requested fellow Muslims to pray for the British-Ottoman friendship to be prosperous.” On 24 April, it was written, “[…] he was the guest of Sheikh Miran Baksh in Lahore.”

He wrote a letter in Persian from Lahore to the Promised Messiahas, the translation of which is as follows:

“O one with saintly virtues! I came to know of your great character and virtues through your faithful followers in Lahore who also introduced me to your magnificent writings. Therefore, I feel a great desire to visit your illuminating persona. God willing, I will travel from Lahore and, via Amritsar, I shall reach your august company. I shall send further details through a telegram. Best regards, Husyein Kami, Consul of the Ottoman Sultan.” (Majmua-e-Ishtiharat, Tracts and Bills of Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian, Vol II, Tract dated 24 May 1897)

The letter copied above is not dated but it is not wrong to assume that it was written at the end of April while he was in Lahore as the Civil and Military Gazette reported his arrival at Amritsar on 27 April; the letter must hence be dated between 22 and 27 April.

The meeting and Hüseyin Kâmi’s frustration

Before coming to the available details of this meeting, it seems befitting to mention that Hüseyin Kâmi left Qadian in so much disappointment that he wrote a defamatory letter to Syed Nazir Hussein, editor of the Nazim-ul-Hind. The letter appeared in the said newspaper’s issue of 15 May 1897:

“My dear and respected Syed Nazir Hussein, I have received your letter for which I am very thankful. I am grateful that you have enquired about the strange character of Qadian and the Qadiani. I present below, with great confidence, my impressions.

“This bizarre individual has gone astray from Islam and is of heretic nature. His claim of love for the Holy Prophet of Islam is not true as he deems the door of prophethood still open. His confusion in understanding nabuwwat and risalat is ridiculous where he claims that the Quran does not declare the Holy Prophet Khatam-ul-Mursilin but only as Khatam-ul-Nabiyyin.

“Cutting it short, he claimed first to be a recipient of wahi, then became the Promised Messiah and has now stationed himself at the status of Mahdi. I seek God’s refuge on how he has styled himself as a prophet. His next move, deluded as he is, might well be that he claim divinity […]

“I request you to ignore his claims completely and leave him to his fate. I beg your pardon for the disturbing words that I have written.

“Convey my regards to Abu Said Muhammad Hussain and Darogha Abdul Ghafur Khan. If you may please let me know of your shoe size so I may order for you a soft shoe from Istanbul and present it to you. Wassalam, Hüseyin Kâmi”. (Ibid)

He had met the Ahmadiyya delegation who must have informed him about the claims of the Promised Messiahas; the Anjuman-e-Islamia must have briefed him too. Then what was it that left him so upset that he ended up writing such heated words in his letter?

Let us get, through the words of the Promised Messiahas, an account of their meeting. Hazrat Ahmadas categorically denied the claim made in the letter and the editorial note published by Nazim-ul-Hind that Huseyn Kami was invited to Qadian so that Hazrat Ahmadas could pledge allegiance to the Ottoman Sultan at his hand.

Hazrat Ahmadas states, “I do not need the Ottoman Sultanate, nor am I inclined to meet their consuls. There is only one Sultan for me and He is the One who presides over the Heaven and the Earth.

“What worth could a worldly kingdom hold over the heavenly kingdom? Much less than what a dead insect holds over the sun. If the Sultanate is so trivial before our King, then of what value is its ambassador?

“In my eyes, it is the British government that deserves respect, obedience and gratitude, under whose rule, I can peacefully carry out my heavenly duties.” (Ibid)

Hazrat Ahmadas also wrote that it was Kami who had asked for a private audience and that he had only approved of it as a gesture of hospitality; knowing well of the worldly and hypocritical intentions behind this audience.

The Promised Messiahas stated: “I was requested to perform a prayer for the Ottoman Sultan for a particular matter, and also to inform Hüseyin Kâmi, through divine knowledge, of the future of his empire.”

In reply, Hazrat Ahmadas told him clearly that the state of the Sultan and his empire was not at all in a good state. “The Ottoman sultanate is in many ways at fault in the eyes of God”, Ahmadas informed him. “God cherishes piety, purity and sympathy for mankind whilst the current Sultanate desires destruction. Repent, so you may gain favour.”

Ahmadas also made his own claims of being the Mahdi and Messiah, in great detail. Moreover, rectified the common but false concept of a “bloody Messiah”.

The conversation must have taken an unpleasant turn for him when the Promised Messiahas declared: “It is God’s intention that any Muslim who is not with me will perish; be it a king or not.” (Ibid)

Following this conversation, he asked for Huzoor’s ideas about the British Empire. The Promised Messiahas replied:

“I am earnestly loyal and grateful to the government since it allows us to live under peaceful circumstances. I don’t believe this level of peace can be achieved under any other empire. Could I be in Istanbul and freely propagate my claims to be the Mahdi and Messiah? Or that jihad by the sword is a false notion. Would the wild maulvis and mullahs not attack me after hearing this? Would I not be required to abide by the beliefs of the Sultan? What use for me, then, is the Ottoman sultanate?”

There were three aspects of this conversation that dampened Hüseyin Kâmi ’s intentions:

1. A claimant of embassy for the heavenly Empire who finds the Ottomans worthless

2. Claimant of being the Mahdi

3. One loyal to the British Empire that accommodated him as ambassador of the heavenly empire

Let’s take a closer look at each of these points; the first and the third together and then the second one in detail.

As far as finding the Ottoman Empire trivial in comparison to the heavenly Empire goes, it is already enough to demolish Hüseyin Kâmi’s Pan-Islamic motives. In the third point, the Promised Messiahas praised and, owing to religious freedom, showed loyalty to the British Empire. Since the Ottoman Empire fell significantly short in contrast, it became clear that the Promised Messiahas and his followers would never join any movement in favour of the Ottoman Sultanate.

1897 was the rule of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. Not only did he witness the steady downfall of his Empire, but his authority was also in decline. He was already fearful of the ever-expanding Western powers and also of new ideologies like that of the “Young Turks” at home. To at least secure religious backing from Muslims, the need for reviving his position as Khalifat-ul-Muslimeen was felt like never before. (Survey by AJ Toynbee)

Therefore, the whole play of pan-Islamism was a ploy to paint his political position in shades of religion. He was also aware that one office that could call for Muslim unity was that of the awaited Messiah and Mahdi – the centuries old fascinations of the ummah for a saviour.

The apprehension of Sultan Abdul Hamid II regarding claimants of Messiahship or Mahdiship can be read in Lothrop Stoddard’s book, The New World of Islam. He was also aware that, being the “custodian of the two holy shrines” was the only reason Muslims respected him. That office would have to be surrendered to a Mahdi or Messiah, if claimants were to emerge on the scene.

The bloodshed by the Mahdi of Sudan was a prototype of what the Sultan was apprehensive about. (RL Shukla; Toynbee)

Bearing this in mind, one can easily imagine how disappointed and frustrated Hüseyin Kâmi must have been after his meeting with Hazrat Ahmadas. He had met a person who wasn’t alone but had a large Muslim following, and not only claimed to be the “Mahdi” but also the “Messiah”.

In brief, Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas, for Kami, was no less than a threat to the pan-Islamic canvas that his Sultan wished to paint on.

Azmi Ozcan, in his book, Pan-Islamism: Indian Muslims, the Ottomans and Britain, has categorically stated that Hüseyin Kâmi’s mission had been successful in all Muslim circles but the Ahmadiyya Jamaat of Qadian. (Azmi Ozcan, p. 106)

The end result of the Ottoman ambassador’s vilification against the Heavenly Empire

To have landed in India and set immediately off to a country-wide tour, tells us that he was more of a propagandist than a diplomat.

Apart from his meeting with Hazrat Ahmadas, he thought that his tour had been a great success. This we know from a letter that he wrote back home to the Sultan:

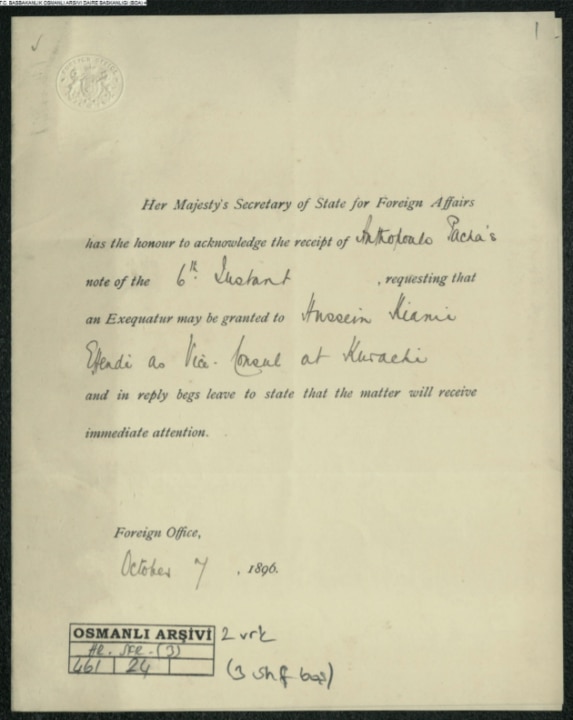

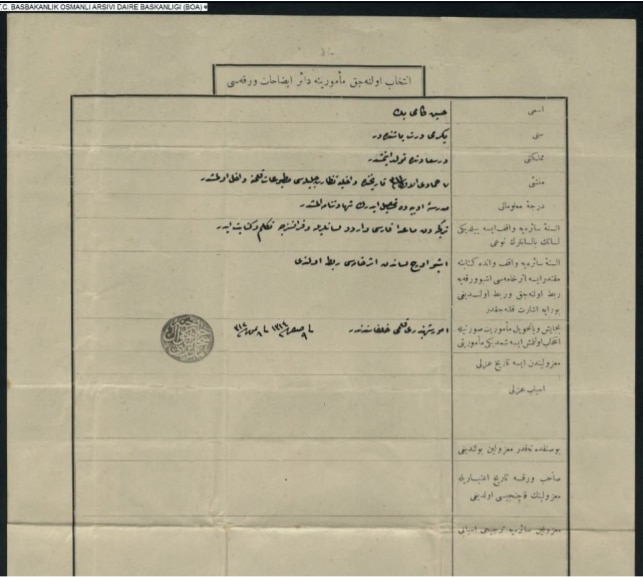

“I have had the honour of being part of the Consulate for a year now and the progress I have made encourages me to continue pursuing consulate services as my career and to benefit from the current enlightenment spread throughout the empire through the solicitude of our Augustus and magnanimous sovereign.” (Ottoman Archives, Istanbul, BOA/I/HR/00352.00047.001)

The date of this letter is unknown, but it is thought to have been written by the end of 1897 (as a pencilled note on the document also suggests) after his all-India tour. This assumption is made on the ground that the letter by the British government accepting his appointment in Karachi as vice-consul is dated 6 October 1896. His letter mentions a year of success since his posting, hence taken to be dated around end of 1897.

He might have thought he was doing well, but fate had decided otherwise.

The year which he thought had been a great success was in fact to bring about his destruction. The British government had been keeping him under close surveillance all along his tour. As mentioned above, the British had only agreed to Ottoman consuls in India on the condition that they would keep themselves to their activities on the ports i.e. facilitating travel to the Ottoman lands. But as we have seen, consuls like Hüseyin Kâmi were there on an altogether different mission.

His pan-Islamic propaganda was an utter dishonesty to the government of the land that he was based in. The British government, based on their surveillance reports, declared Hüseyin Kâmi a persona non grata and asked the Ottoman government to recall him from India. (Secret report, India Office Records, L/P&S/7/103, no 469)

Hüseyin Kâmi’s dishonesty, as it started to become manifest, turned out to be not aimed at the British government but also to his own benefactor, the Ottoman Sultan .

As mentioned earlier, one of the motives behind his tour of Muslim majority regions of India was to secure donations for the orphans of those who had laid their lives during the Greco-Turkish war on Crete in 1897. He was found to have embezzled the funds that were in his possession, suspended from duty and as a result, had faced a great deal of disgrace.

The Promised Messiahas narrated this in his book, Tiryaq-ul-Qulub (1902):

“The funds collected for the victims of Crete, deposited to Hussain Kami as vice-consul based at Karachi, was never received by the Ottoman treasury. Thus, after investigating the matter, his fraud became evident, he was dismissed from his service and the embezzled funds were recovered by auctioning his possessions.”

The Promised Messiahas presented proof from a newspaper, Nayyar-e-Asafi of 1 October 1899 where it was reported under the title, “A Letter from Constantinople”. The news story particularly mentioned that the money donated by the Vakil newspaper of Amritsar, had been part of the funds embezzled by Hüseyin Kâmi.

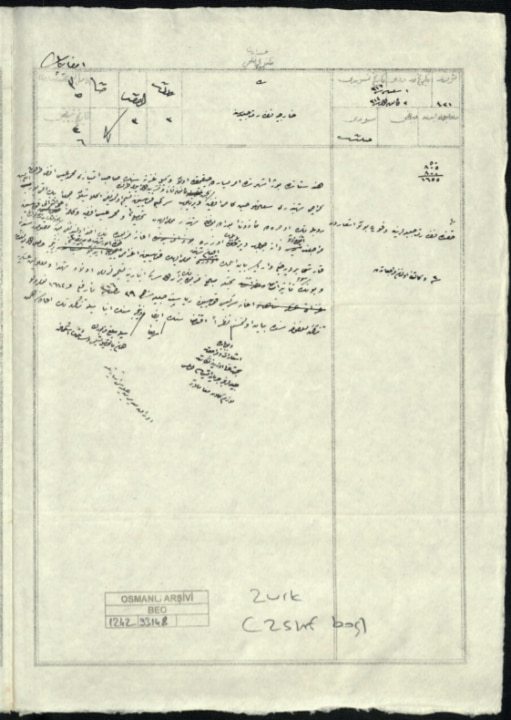

Praise be to Allah, that the Ahmadiyya Archive and Research Centre, London, is now able to present the evidence from the records of the Ottoman Empire. The document found at the Ottoman Archives, mentions the embezzlement of 1,655 robles, highlighting the funds collected by “Muhammad Isa of Vakil newspaper, Amritsar”. (Ottoman Archive, Istanbul: BEO/001242/093148/001)

Greater manifestation of the Promised Messiah’sas prophecy

When Hüseyin Kâmi requested Hazrat Ahmadas to foretell the fate of the Ottoman Empire, Ahmadas informed him of the following:

“The condition of the Ottoman Sultan is not good and what I have seen in a divine vision is that I do not find its associates in a sound state. In my view, what lies ahead is not pleasant.”

The Ottoman Sultan was actually in a terrible state. The good old days of the love affair with the British were now a bygone. For Sultan Abdul Hamid, sympathies of the Indian-Muslims was amongst the last straws he clutched on to in desperation.

AJ Toynbee described the Ottoman state of affairs in the following words:

“Abdul Hamid did, indeed, retort to the new orientation of British policy, which became increasingly unfavourable to Turkey from 1880 onwards, by conducting anti-British propaganda in India.”

The position of an absolute ruler that Sultan Abdul Hamid had enjoyed vanished in thin air when the movement of the Young Turks coerced him to revive the long suspended constitution. With little or no choice, the Sultan had to succumb to the demand and, as a result, found himself a mere constitutional monarch. At last, the Young Turks movement blossomed and by 1908, the self-styled Sultan-Caliph of the Muslim Ummah and the emperor of a great empire, was left with only as much land as covered by his royal palace. Sultan and caliph and emperor were now only titles but with no power.

It is worth noting here that the year when the glory of the Ottoman caliph saw its doom, is the same year when the heavenly caliphate – that had commenced through the Promised Messiahas – came into existence.

After Hüseyin Kâmi’s visit to Qadian and his defamatory letter, the Promised Messiahas published another announcement on 7 June 1897, where he stated:

“Remember that rejecting the chosen one of God, is the rejection of God. You may call me names if you choose to do so, because the Heavenly Empire in your view holds no station. The Sultan’s claim of being the caliph of the Muslim Ummah, is merely a conjecture. In fact, the true Caliphate is the one mentioned in Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya and Izala-e-Auham 70 years ago. Do you not remember the revelation:

اردت ان استخلف فخلقت آدم

[I wanted to create a vicegerent, so I created Adam]

خليفة الله السلطان

[Allah’s Caliph, the Sultan]. Yes, our Caliphate is spiritual and heavenly not earthly.”

How these words were splendidly fulfilled, is an amazing phenomenon!

The year when the Ottoman Empire wanted to establish their so-called Caliphate and appointed Husain Kami to India, was 1896. It was during the same year that it was once again revealed to Promised Messiahas:

“Kings shall seek blessings from thy garments.”

History now bears witness that the words of the Promised Messiahas were true and from the Heavenly Sovereign.

مجھ كو كيا ملكوں سے ميرا ملک ہے سب سے جدا

مجھ كو كيا تاجوں سے ميرا تاج ہے رضوان يار

Post scriptum

The only information that we had in our literature was that one Hüseyin Kâmi, a consul of the Ottoman Sultan, visited the Promised Messiahas in Qadian, left frustrated and wrote libellous words about Huzooras. The motives behind an Ottoman consul visiting the Promised Messiahas were also obscure as the details of the private audience remained private and Huzooras also did not give any details of the “particular” issue discussed.

His date of arrival in Qadian

When he arrived in Qadian has also been unclear all along. In Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyyat, volume I, it is said that he arrived in Qadian on “10 or 11 May”. Sirat-ul-Mahdi does not give any date while Hayat-e-Ahmad by Hazrat Sheikh Yaqub Ali Irfanira also states “10 or 11 May”.

In Maktubat-e-Ahmad, volume II, a letter by the Promised Messiah to Hazrat Nawab Muhammad Ali Khan Sahib is published, stating:

“Your servant arrived yesterday. The consul had himself desired to visit Maler Kotla […]”

With this letter is a footnote by Sheikh Yaqub Ali Irfanira:

“Note by editor: The date on this letter is either 1 or 11 May. Huzoor would sometimes add a line (؍) after the digits in the date, but sometimes he would not. If the line is taken to be added here, the date is 1 May, whereas if it is not, then the date would be 11 […]

“It is clear that the letter was written after Hüseyin Kâmi’s visit to Qadian. Only by knowing the dates of his visit to Qadian can the date on this letter be ascertained […]

“Since I have found out that Hüseyin Kâmi visited Lahore in May before visiting Qadian later, I assume the date to be 11 May.”

During my research, I have been able to ascertain that Hüseyin Kâmi’s visit to Lahore, prior to visiting Qadian (via Amritsar) was from 22 April 1897 to 27 April 1897.

The Civil and Military Gazette, in its issue of 23 April, reports his arrival to have happened “yesterday”, i.e. 22 April.

The issue of 24 April again confirms his arrival on 22 April.

The Civil and Military Gazette, Lahore, of Thursday, 29 April reports that Hüseyin Kâmi had arrived in Amritsar on Tuesday, 27 April. It was from here that he was to head to Qadian, as he suggested in his itinerary when he wrote to the Promised Messiahas.

All this is sufficient to confirm that Hüseyin Kâmi’s visit to Lahore was during the month of April and not May. As his stay in Lahore was only for five days and he remained an even lesser number of days in smaller towns, it is plausible that he visited Qadian in the last days of April, and the letter of the Promised Messiah is probably dated 1 May.

As the only possibility of the letter being written on 11 May is said – in the footnote of Maktubat-e-Ahmad – to be Kami visiting Lahore in May, it is now even more probable that his visit to Qadian was in the last days of April 1897.

His letter to the newspaper Nazim-ul-Hind, published in its issue of 15 May, seems to be written to the newspaper upon the editor’s request. This is evident from the opening lines that read, “How thankful I am that you have enquired about my impressions on Qadian and the peculiar character of the Qadiani […]”

To appear in the issue of 15 May, the letter would have been included in the copy of the paper a day before. For the two letters to have travelled to and fro, even by the fastest mail service of those days, would have taken at least three days each. This pushes the date of Hüseyin Kâmi’s letter – which was written after he had departed from Qadian – prior to 11 May.

If we suppose the Promised Messiah’s letter to Nawab Sahib to be dated 11 May, that means he had left Qadian by then. This again suggests that he could not have arrived on 10 as all accounts of his visit suggest that he arrived around the time of Isha. The Promised Messiahas was suffering from a migraine and could not attend to him. The meeting, therefore, took place the following day.

This too suggests that he had visited Qadian before 10 or 11 May and the letter, most probably, was written on the 1st.

All this is not said with certainty but adds newly found material to the discussion. We might one day be able to say with certainty, insha-Allah.

Hüseyin Kâmi’s name

It took a lot of effort to reach the Hüseyin Kâmi that we required for this research. The misguiding element was that many researchers and historians have recorded his name as “Hussain Kamil” or “Huseyin Kamil”. With the airs that come with great researchers and scholars (and publishers like Cambridge University Press, Brill and their likes) we took it to be so and the research remained on a stray path.

It was not until I was able to tap on the Ottoman Archives and in Istanbul, and other Turkish sources, that I discovered the correct spellings of his name to be Hüseyin Kâmi.

Confirmation of Kami’s misfortunes

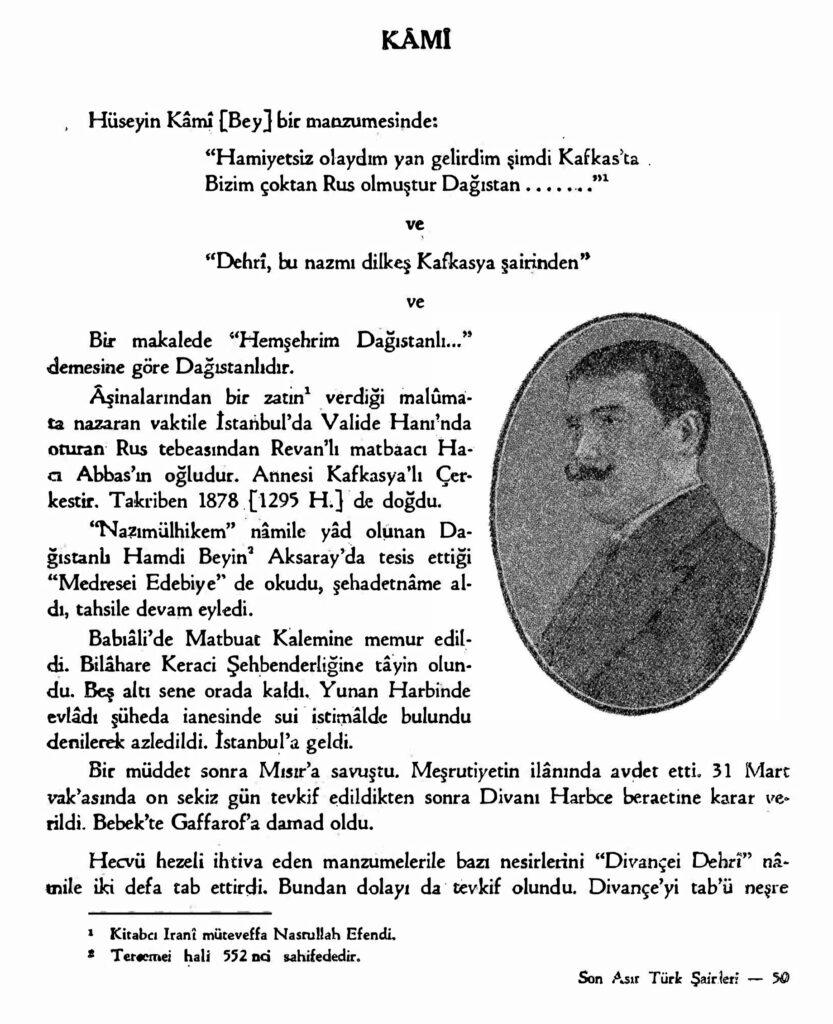

I found out that Hüseyin Kâmi was a poet and had his works published under the name of Dehri Daghistanli. He used other pseudonyms as well. The main collection of his poetic works was published under the title Divance-i Dehri.

A book titled Son Asir Turk Sairleri (Turk poets of the last century) by Mahmud Kemal Inal introduces him in the following words:

“Hüseyin Kâmi associated himself to Daghistan as his father was of Daghistani descent. He was first employed in the printing press of the Porte Noble of the Sultan before being appointed as consul at Karachi. He remained there for five or six years. He embezzled funds collected for the orphans of those that laid their lives in the Greco-Turkish war and was, thus, suspended from his job.”

Turkish historian Sefer E Berzeg has revealed in his articles, published in the daily Tanin, Istanbul, that Hüseyin Kâmi was not only suspended from his duties, but was exiled to Egypt where he had to endure hard labour as part of his penalty. He was recalled to Turkey after the revolution of 31 March 1909 where he was tried for various crimes and remained in and out prison for the rest of his life.

Mahmud Kemal Inal, in his above-mentioned book, has also mentioned the poetic works of Hüseyin Kâmi. His most famous work is Divance-i Dehri which is a collection of his satirical poetry.

Inal has recorded his year of birth to be around 1878, and 1912 as that of his death. However, Dr Ahmed Tanyildiz, who has carried thorough research on Kami’s Divance-I Dehri, is of the opinion that the year of birth and death, as stated by Inal, are not accurate. His research shows that Kami passed away around 1916.

In the documents that I was able to obtain from the Ottoman Archives in Istanbul, his age is recorded to be 24 in his service records. The document is dated 1897, which takes his year of birth to 1873. As this does not add or take away any substance from the scope of my research, I leave it for Turkish historians to decide.

(Translated by Tahmeed Ahmad and Azhar Ahmad, UK)