Various revelations and dreams predicting a multitude of plagues, wars, epidemics, earthly and heavenly sufferings etc. were vouchsafed to the Promised Messiahas and that occurred in the past as prophesied. Even today, the world is experiencing many catastrophes and outbreaks.

On the other hand, the holy founder of the Ahmadiyya Jamaat established a devout and selfless community which continues to carry out a Jihad of service to mankind, under the leadership of Khalifatul Masih. It emerges that their motto is to envision this poetic attribute of the Promised Messiahas which is stated in the following couplet of his:

مرا مقصود و مطلوب و تمنا خدمتِ خلق است

ہمیں کارم ہمیں بارم ہمیں رسمم ہمیں راہم

“My purpose, yearning and heartfelt desire is to serve humanity; this is my job, this is my faith, this is my habit and this is my way of life.”

After the sad demise of the Promised Messiahas, World War I soon broke out. Rough estimates suggest that the war (1914-1918) claimed 20 million lives. This was followed by the 1918 influenza epidemic, which was the most severe pandemic in recent history and was caused by an H1N1 virus. In the United States, it was first identified amongst military personnel in spring 1918. It is estimated that about 500 million people or one-third of the world’s population became infected with influenza. The number of deaths was estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide.

Then came World War II, which lasted for around six years from 1939 to 1945 and annihilated another 85 million people around the world.

God forbid, if any disease, pandemic or any other health catastrophe had surfaced after these disastrous six years, the suffering would have been unimaginable.

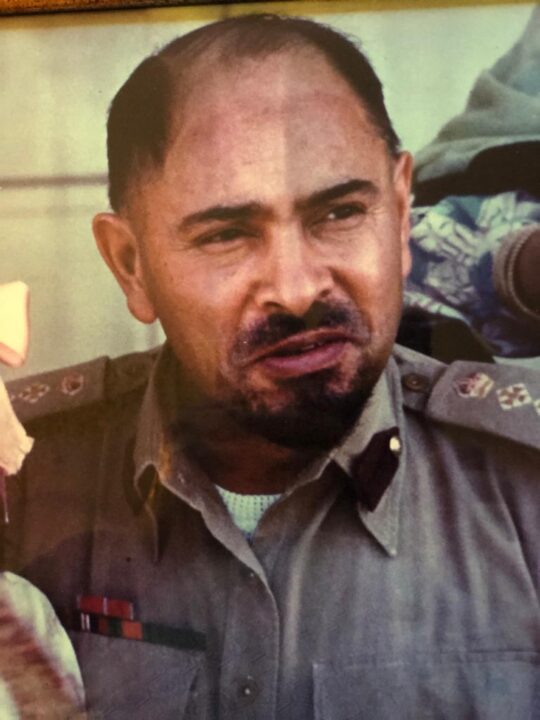

Col Muhammad Ata-Ullah was born in the early 1900s, to a devout Ahmadi family. After studying medicine in Lahore and London and graduating in 1928, he served as a doctor in the Indian Medical Service of the British Army before the partition of India and Pakistan.

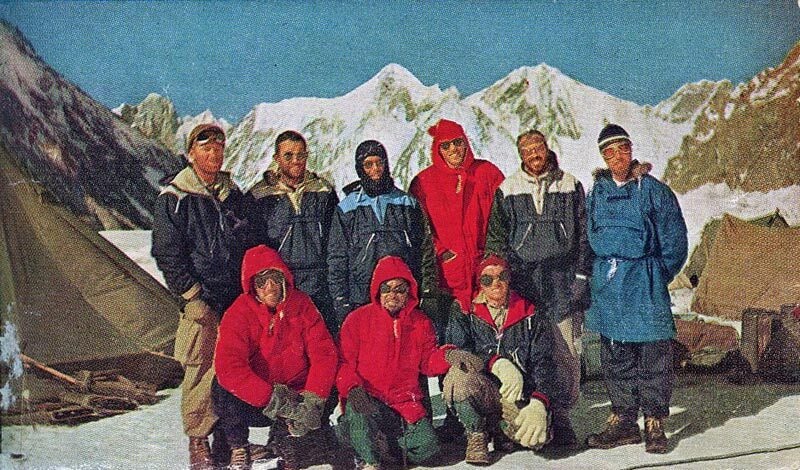

During his rich career as a doctor, an army officer both in the British Raj and with the Pakistan Army, as a remarkable mountaineer (joining the American expedition to K2) and finally as a philosopher, he unarguably achieved many remarkable milestones.

After the creation of Pakistan, Col Ata-ullah became the first Director of Health Services in Azad Kashmir and continued his career in helping wounded troops both in Japan and Korea. Here we shall highlight one of his highly acclaimed accomplishments, which relates to our present day as well.

So here, we produce an account of an Ahmadi who helped prevent an outbreak during World War II. He was a frontline army officer deployed in Iran. This account is directly taken from his autobiography: A Citizen of Two Worlds.

Once, Ata-Ullah Sahib was assigned with a novel task called “Operation Pole-Evac”, as he states:

“On a certain day I was hurriedly wakened in the middle of my siesta to attend an emergency conference called by General Lane in premises of the British Embassy, who has just returned from General Headquarters at Baghdad with an instruction to set up ‘Operation Pole-Evac.’ Actually, in the earliest days of World War II, the central European nation Poland’s natives Poles displayed the unequal fight, first against Hitler and then against the Russians, who captured vast numbers of prisoners. One group of over two hundred thousand Poles has been held for the last three years in a certain area of Soviet Central Asia.

“But at that stage of war, we are pointing at, the Poles and the Russians were not enemies, but allies in their common war against the Germans. Many Poles were already fighting on the front. It was decided that the Poles now in Soviet Central Asia will be brought to the Middle East and formed into new armies to reinforce us. But many problems intervene. The distances are long; communications are primitive. So this Polish evacuation will be a lot of fuss and bother; it is going to be the devil. This new war was going to be fought on the southwest corner of the Caspian Sea. This is the port of Pahlevi, two hundred miles from Teheran on a dirt road. The Russians will bring the Poles by railroad to the port of Krasnovodsk, and then across the Caspian to Pahlevi. On landing at Pahlevi, [they will] become British responsibility. The main supply centers are a long way off in Iraq, from which Pahlevi is a difficult sixteen-day round trip. British organizers must quickly move the Poles back nearer to our supply centers. Too many must not accumulate at Pahlevi, though the British Army must be ready to deal with any hold-ups.”

Col Ata-Ullah Sahib recalls:

“Each of those present in conference was told his responsibility in detail. I was alternately fascinated and frightened. I felt I was a piece in a human jigsaw puzzle, and that if I made any mistake the thing would no longer fit. This was my first important assignment since getting unexpected promotion from major to lieutenant colonel, and I was as worried as an unprepared student at his final examination. But there was a heartening note of confidence in the general’s tone; he seemed to have thought of everything. The important question about Pole-Evac was this: What would be the peak number of Poles in Pahlevi at any one time? This depended on how fast the Russians brought them, and how fast our transport moved them to the rear areas. On both these points there was some uncertainty. The road out of Pahlevi was a narrow dirt track, and no one knew how it would stand up to heavy traffic or bad weather. We had about a hundred lorries, and for the distances involved, these would take away about two thousand Poles a day, when things went well. The Russians had said that once the evacuation began, about five thousand Poles would land every day. Fortunately, this was considered impossible by our intelligence staff.

“There was only a single-track, low-capacity railroad into Krasnovodsk. The Soviet merchant fleet on the Caspian Sea was small and even with the whole of it on the Pahlevi-Krasnovodsk run, the Russians could not carry more than a quarter of the numbers they had promised. This was a great relief, since otherwise the bottleneck out of Pahlevi would inevitably lead us into rapid chaos. Soon General Lane was addressing me: ‘Ata-Ullah, the medical side will be your responsibility, and you will be hard pressed. Our medical services are badly stretched out in the battle areas of the Western Desert. I can get you no reinforcements. Do the best with what you have already got.’ ‘Can I at least hope, sir, that all these Poles will generally be in good health?’ was my embarrassed comment. ‘I am afraid I cannot be definite’, replied the general. ‘We did ask the Russians about their health, but we got no reply. Like millions of others in Russia, these Poles have probably been getting insufficient food. The possible effect on their health you can judge for yourself. There are vague reports of some typhus fever, though presumably no one will travel while actively suffering from such a disease.’

“I was asked about my existing resources, and it was agreed that they were small. Including me, we had nine doctors; our enlisted men were mostly litter bearers. As the normal function of my regiment was only to give first aid or emergency treatment, we were not equipped or staffed to take continuous care of patients. At Pahlevi we would need a hospital, and until one could be brought up, I asked for more doctors. My plea was brushed aside with a courteous smile. ‘I know all that’’ said the general. ‘You may expect more medical supplies shortly, and in the meantime I give you unlimited authority to buy anything you want urgently and can find in Teheran and Pahlevi. Use local resources; improvise; but do not waste your breath in asking for more doctors. War is war.’

“By noon on the following day, I was ready to leave for Pahlevi with Maula Bux and Shambhu Ram, my personal driver. The rest of the regiment would move up later. On the way, I had to pick up, at the British Embassy, a permit for travel into the zone of Russian occupation. Also, I wanted to use the authority given to me by General Lane to buy ten thousand hair clippers. What worried me most about Pole-Evac was typhus, a dreaded disease with no effective cure. It is an ever-present danger when overcrowded people do not have enough clothing and lack washing and bathing facilities. It is very infectious, and once out of hand it spreads like a prairie fire, often decimating entire populations. It is carried from person to person by lice, which, under such conditions, grow by the million in the clothes and hair of helpless, unwilling human hosts.

“If the Poles did bring in typhus, our most desperate need would be to get rid of their lice at once. This was before the days of DDT and I wanted to give a pair of hair clippers to each arriving family and request them to put these to vigorous use. But unfortunately, the combined efforts of the regiment did not buy us more than one per cent of our needs. Having cleared Teheran of hair clippers, we proceeded to the British Embassy. The pass from the Russians had not arrived, so I was told to go on without the pass. The Russians assured us that their commanders on the route had orders to let us go to Pahlevi. I did not like this much. However, this was not the case as we travelled to our destination.

“My first sight of Pahlevi was depressing; it was even smaller and more ramshackle than I had imagined. The one thing of significance that we saw as we drove in was a small walled-in factory called Iranryba, widely known for its good caviar.

“I met the local Russian commander, Major Kadimoff, who knew of the Polish evacuation, and I briefly explained my own place in it. ‘My resources are very limited’, I said, ‘and you and the Persian medical people must help in every possible way. This is a common problem, not only for humanitarian reasons, but also because none of us can afford an epidemic.’

“But the whole Russian side was providing me one Persian doctor. I was trembling. Even he had been rushed to Pahlevi in a hurry with only a vague idea of what he was to do. Finding a sympathetic professional colleague, he readily unburdened his woes. ‘I have been given no staff’, he explained bitterly, ‘so what can I do here anyway?’ ‘Nothing’, I agreed. I then suggested that he pool his resources with mine, and let me take over the local hospital. ‘Gladly’, he said. ‘Perhaps I will then be allowed to go back.’

“The hospital was a small well-built place, with room for about twenty patients. It was surrounded by spacious open lawns. But there were no patients, no equipment, no staff. The Persian doctor was glad to give me immediate possession of the empty hospital, and also of the open lawns as a campsite for my medical regiment. We then went around the whole town, but found little of any use either for love or money. My only luck was to find two establishments with running hot water, and I eagerly signed them up for exclusive use during the Polish evacuation. One was the small solitary Turkish bath of the town, and the other was the shower room of the caviar factory. Apart from some office rooms no buildings were available. The arriving refugees would have to stay on the open beaches until they could move out.

“Three days later, late at night, I received a message from Kadimoff that the first shipload of Polish refugees was due at Pahlevi at dawn. About an hour before its expected arrival, I walked down to the jetty where she was to berth. The jetty was without any shelter; it was only a paved, open space with some wet wooden benches here and there. I walked over to the corner where my medical regiment had set up a first-aid post to take care of anyone who might have fallen ill on the voyage from Krasnovodsk. Someone spread out a blanket on one of the benches and invited me to sit down. A few minutes later, a thickset figure wrapped in a greatcoat appeared out of the mist and came in my direction. This was Ross. He joined me on the bench. ‘I have good news for you’, he said. ‘The chief of the Polish medical services is on board this ship. His name is General Szarecki. I knew him well when I was in Warsaw, where he had a great reputation. He is sure to be bringing many doctors and other medical staff with him, and we can let them take care of their own sick. They will need your advice on local conditions and your help in emergencies; but generally you should have an easy time’. ‘That is good’, I replied. ‘I feel much relieved. Do we know now how many refugees will come in today, and how many of them will need urgent medical care?’ ‘No, we can’t be sure of anything until they are here. We have scanty information, as the Russians have chosen to tell us little. But we shall know as soon as the first Poles come in.’

“Suddenly I felt a peculiar unpleasant smell in the air. Ross sniffed and agreed. I tried hard to place the smell, but could not put a name to it. To catch it better, I turned in the direction of the splash, which had seemed somewhere in the swamp. But I found that the smell was coming from the opposite side, from the direction of the open sea. I walked over to the first-aid post. ‘What is this bad smell?’ I asked. ‘Are there any foul sweaty clothes lying about? We must do something about it at once. We must find where this smell comes from.’ ‘That’s what we have been asking ourselves,’ replied one of the soldiers. ‘It seems like a putrefied dead body.’ ‘More like the stink from a bad latrine’, suggested another. The smell was increasing. It seemed to be a mixture of many different odors, all intensely foul. Soon it had become unbearable. Someone suddenly announced that the Russian ship was in the harbour and would be coming alongside any moment.

“By now, a few other persons had also arrived at the jetty: Kadimoff as the guardian of law and order; the Persian doctor to see that none of the refugees brought in infectious disease; some Polish officers to welcome their compatriots; a representative of the American Red Cross; some officers and men of Ross’ staff.

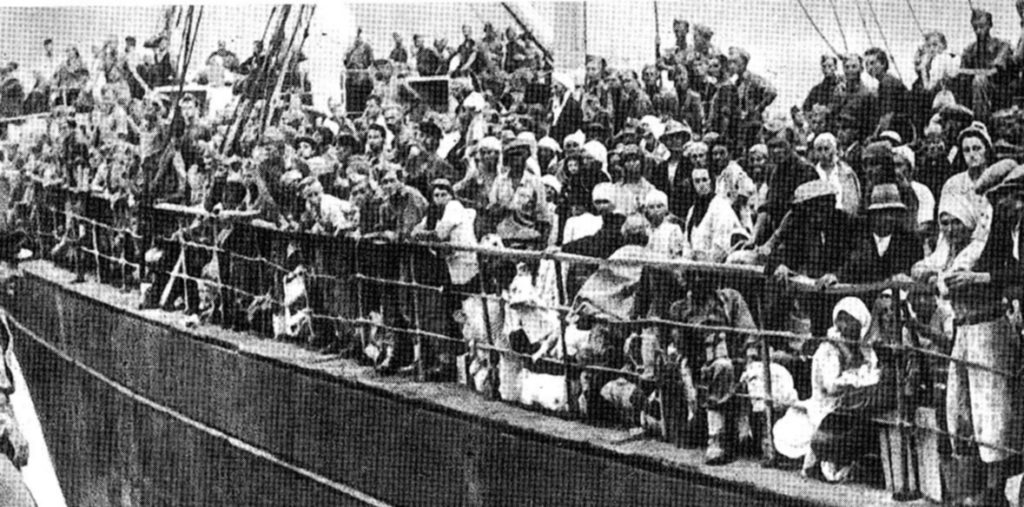

“Everyone was holding their nose against the foul smell. Suddenly it overpowered me. I felt a writhing upheaval in my stomach and my legs began quivering from weakness. I was just able to reach a corner of the first-aid post, where I vomited violently. I was brought round from my misery by a loud chinking of chains and looking up in the bleak light of that misty dawn, I saw that the dimly lighted ship was alongside. It was a tanker. Its open top deck and all other space were packed with people standing shoulder to shoulder with hardly any room to move. They were mostly men, but there were women and children too and babies in arms.

“Their clothes were tattered, their shoulders drooping, their heads bowed, their ashen faces shriveled, drawn and silent; they were the picture of utter and abject misery. I do not know what I had expected, but I was aghast at that sight. Here was the source of those foul and revolting odors which had puzzled us. Here was a mass of humanity, filthy, diseased, exhausted, utterly broken. Someone tried to raise a cheer in welcome, but it only sounded a discordant note in that atmosphere of stark tragedy.

“There was not even a feeble response from the exhausted multitude on the ship. Their lusterless eyes in their sunken sockets looked at us without any show of interest. I felt like a dumb, helpless, weary spectator at a funeral who wants to run away, but does not have the courage to defy appearances. I tried to withdraw myself from those unbearable sights and smells, and to think of other things. But one thought returned again and again to my mind: my own immediate responsibility toward these people.

“My medical regiment had been sent to Pahlevi to look after them. I had been anxious to find out how many sick persons we would have to care for, and so far I had got no reliable information. Now the plain, unmistakable answer was staring me in the face. Every one of these refugees was sick, in mind and in body. Every one of them would need prolonged medical care. If this shipload was a sample of what was to follow, it was quite beyond the worst that I had expected. We would be overwhelmed.

“‘This is terrible’, I heard Ross say softly at my side. ‘I do not know how you are going to cope with it.’ ‘Nor do I’, was my despairing reply. ‘The second ship is due in a few hours’ he went on, ‘and the Russians want the first one emptied quickly. We must make some immediate plans to deal with the situation.’ ‘Yes, we must I agreed. Give me half an hour to recover from this shock, and to think things out. After that let us meet with Szarecki and get all the details. I greatly fear that we have a serious epidemic on our hands.’

“I walked back to the grounds of the small local hospital where my medical regiment was in camp. It was a relief merely to get away from the close neighborhood of the ship, though there was no escape from that foul smell, which was now everywhere. As soon as I entered my tent, I felt an irresistible desire to scrub and wash myself. And then for my pent-up fears and anxieties, I sought comfort in a long and anguished prayer.

“General Szarecki soon confirmed my worst fears. ‘We had epidemics of typhus and dysentery at all the camps at which we have stayed’, he told us. ‘We have suffered these epidemics for the past four or five months. Conditions were such that we were able to do nothing to stop them.’ My heart sank as I asked him the questions uppermost in my mind: ‘But I hope you have left behind those who were suffering from such diseases at the moment. The Persians would not like any epidemics introduced into their country.’ ‘I am afraid it was impossible to leave anyone behind’, answered Szarecki in a melancholy voice. ‘We had to bring out everyone, young or old, sick or well. The Russians insisted on that. As for us Poles ourselves, it was clearly now or never; and none of us was willing to remain behind. This is like the exodus of Israel from Egypt. We decided not to leave behind even women in childbirth, even men on their deathbeds. Everyone had to move with his group.’

“Szarecki then told us of the tortures suffered on the journey. It was generally known that conditions in the Polish camps inside Russia had always been bad. That matters became worse when the most productive parts of the country were overrun by the advancing German armies was understandable. But I found the inhuman story of that journey out of the Soviet Union, as now related by Szarecki, cruel and grim beyond belief.

“The first part of the journey was by railroad. For this we had open cattle trucks, where everyone was given standing room only. The trucks were packed until there was no room to move. Personal belongings were not allowed beyond what could be carried by hand. Food, water and toilet arrangements were almost nonexistent, even though in some cases the train journey lasted over two days. Many had to go on board this tanker straight from the cattle trucks, with no chance for any rest, wash or sleep.

“The sea journey was a never-to-be-forgotten nightmare. Here again there was no more than standing room, but as we were packed more tightly, the feeling of being strangled and suffocated was worse than in those cattle trucks. Many were continuously seasick; and they could do nothing but vomit where they stood. Those who had the strength and the will to struggle got to the edge of the deck to answer the calls of nature, but few had that much strength. In that worse than animal existence, it was impossible to keep up human decencies and soon the place was solid with urine, faeces and vomit. Many found the stink of filth and the stench of disease unbearable and fainted. At least they found temporary deliverance, though it was impossible to do anything for them.

“They stayed where they were, often held up in their sagging unconscious state by the pressure of human bodies around them. Eighty out of every hundred are so ill that they need long hospital care. And there are many emergencies. Two women have had abortions, one has given birth to a living baby during the journey. There were two deaths from typhus, and about ten persons seem too far gone to be saved unless you can do something for them quickly. Ship after ship is to follow us, until two hundred thousand Poles are landed in Pahlevi. They will all be in the same condition.

“My heart sank at this fearsome responsibility and I did not even know where to begin. But I knew there was no escape. The urgent need was to stop the epidemic by isolating all the Poles until they could be examined one by one. Szarecki confirmed my worst fears: that everyone was infested with lice, both on their bodies and in their clothes. We would have to get them clean and into new clothes. What they wore now were mere rags; these must immediately be burned. Fortunately, Ross had good supplies of soldiers’ uniforms and blankets. With good discipline and a twenty-four-hour working day at the Turkish bath and the factory shower room, we might avert a bad disaster. ‘How about the seriously ill?’ asked Ross, putting into words the question that I was dreading. I felt like a criminal, but I could give only one answer. ‘Many patients were brought to hospital straight from the jetty’ I explained. ‘More followed soon afterward. When the beds were gone, we put them on litters in the corridors. When the corridors were full, we moved the Indian soldiers out of their tents and turned the tents into wards. Even they are full. We have now closed the hospital to everyone.’ ‘Even to a person on the point of death?’ asked Ross incredulously. ‘Yes’, I said sorrowfully. ‘But in a day or two, when General Szarecki has reinforced us by his available doctors and nurses, things may be better. Even then we must select the patients whom we can hope to really help.’

“The fact was that we had to set up priorities, and those beyond help had to be allowed to die peacefully in some corner of the beach. I remember few details of the next twenty-four hours. For the whole of that period, every officer and man of the medical regiment was continuously on his feet, continuously at work. Until the arrival of the first Polish ship, typhus had been primarily a name to most of us. Neither I, nor any of the other doctors at Pahlevi, had seen more than an occasional case of the disease, and then always in the organised safety of special infectious-disease wards. I now recalled my first contact with typhus as a medical student and found myself gripped with fear. I had read up on the disease again, but the latest literature also showed frightening gaps in the scientific understanding of the disease. It could take different forms with many variations in signs and symptoms. It could catch you suddenly, but it could equally creep up on you insidiously from minor beginnings. A harmless itch, a pain or ache anywhere in the body, the mildest fever or cold and your imagination ran wild with fear if typhus was about. No cure was known. All that the doctors could do was to deaden the sufferings and the pains while the disease ran its unyielding, unpredictable course. By the time of Pahlevi, however, a preventive vaccine had been produced which was believed to confer a useful though not a high degree of immunity. Unfortunately, our supplies were small. After Ross and the key members of his staff had received their injections, there was only enough for about a quarter of the personnel of the medical regiment.

“I discussed this at an officers’ meeting and invited views on who in the regiment would run the greater risks. There was no agreement. This was not surprising, and since all of us would be in great enough peril there seemed little point in making fine distinctions. So the sickening, agonising decision about who would receive that injection and who would go without it was left to me. My own mind was quickly made up and I gave necessary instructions: ‘Act on first come, first served, or draw lots if you wish.’

“Szarecki, it soon became clear, would not be able to reinforce us much. He sent us a few doctors and nurses, but they were semi-invalids themselves. They would be part patients and part staff and I invited them to decide for themselves how they could best serve their sicker countrymen. That the medical regiment would carry the burden practically unaided in that crucial early stage was doubly sad; it dimmed my hopes for a quick stop to the epidemic; it lessened the chance of succor for those already in the grip of the plague.

“I felt cornered, trapped and desperate. And then, suddenly, a merciful providence blanked out Pahlevi from my mind, and I was deep in the vivid recollection of the scene that had taken place six months ago at the railroad station of Qadian. Father seemed to be again with me, holding me in his loose embrace. I was bending low for his kiss; he was telling me that God never turns down a cry in distress. Surging through my mind was that familiar passage from the Holy Book: ‘When My servants ask about Me, tell them that I am always near. I answer the supplicant whenever he calls Me, only let him do My bidding and have faith in Me, so that he may be rightly guided.’

“Father had a simple philosophy about the place of prayer in the scheme of things. ‘Do you want to know’ he would ask, ‘how quickly God’s love responds to prayer? Then let a mother tell you how fast rises the milk in her breasts when her helpless infant utters a hungry cry. No genuine prayer is fruitless, though for our own good the result is often different from our wishes. Beware of being like a child who doubts his mother’s love when she holds him from the irresistible lure of the flame.’

“‘There are laws of nature made immutable by divine will, but within their scope prayer can work miracles. You will ask in vain for the dead to be returned to life, but prayer may so tame the winds and waves that their own murderous fury deposits you on the shore. What you get from prayer will depend on what you take to it. Offer humility and you will find strength; offer grief and you will find solace. It will bring you peace instead of vanity in worldly gains. At best it will lift you beyond the stars in the skies, and always it will sustain the sanity of your spirits. In your greatest trials, pray and you will find sources of inner strength that you had not even dreamed of before.’

“Amidst the woes of Pahlevi, the memory of that farewell scene came to me like a breath of fresh life. One instant I was baffled, desperately agitated; the next my mind was cool, my spirits calm and peaceful. No longer did I feel paralyzed and crushed. What if it seemed beyond my resources to control things properly? That was no reason why I should not meet the challenge to the utmost of my ability.

“By early afternoon, order began to replace the chaos both in my surroundings and in my inner self. The few hours that had passed since that grim arrival of the tanker at dawn seemed like days. All that I had heard and seen in the meantime had confirmed my first tragic assessment.

“The medical regiment threw itself into the work wholeheartedly and by evening, a pattern had been set which continued uninterruptedly on the beaches and streets of Pahlevi for over a fortnight. The plan was simple. Immediately on landing, all the refugees were escorted to a special ‘dirty’ camp on the beach. They were guarded like prisoners and forbidden to go out until they had been through the cleansing process. For this we took the women and children to the Turkish bath and sent the men to the shower room of the caviar factory. Their rags were taken away and burnt, they were shorn of their hair and rid of their lice, their dirty bodies were soaked and scrubbed clean. Each person was given new blankets and a soldier’s uniform and sent back to the beach to another camp. This was the ‘clean’ camp, and here in greater liberty he waited his turn to leave Pahlevi.

“Under normal conditions we should have gone further and kept the inmates of the ‘clean’ camp also under guard for another ten days. Many might be incubating the disease without outward signs of it. But I decided not to attempt the impossible, and to concentrate all resources where they would be most effective. In the early stages, we had to forget those incubating the disease, just as we had temporarily steeled our hearts against those who were too ill.

“Many times during that day, I made the rounds of the main scenes of activity, cheering and praising and comforting and exhorting; giving a symbolic helping hand in one place and in another ordering off duty those about to drop from fatigue. Ross and his staff worked wonders in their own field. In the evening I went over to see him and to compare notes, and then together we walked over to see Kadimoff.

“For ten long days and nights, the Poles poured into Pahlevi like a flood. How many were to come on any particular day was never known beforehand. One day only a hundred; on the next, many thousands. There was a merciful day when no ship came at all, but there was another, which, even though years have gone by, I still recall with a shudder. On this tragic day, twelve thousand human wrecks were flung ashore. The flimsy organisation of the medical regiment broke down and Pahlevi became a seething chaos for twenty-four hours. But powerfully aided by many of the Poles who had arrived earlier and whose gallant spirits now gloriously burst out of the limitations of their sick bodies, we were soon in control again.

“General Lane had talked of two hundred thousand Poles in Soviet Central Asia. The senior Polish officers in Pahlevi said that there were many more. But to our great surprise, on the tenth day of the evacuation Kadimoff announced that it was at an end. Only forty-three thousand Poles had reached us so far.

“This caused consternation among the Poles, though my own first feeling was of great relief. Transport out of Pahlevi had been slow; thirty thousand Poles were still on our hands. Our ‘dirty’ camp was hopelessly congested. Even with no more arrivals it would be another week before everyone could be given his first hot bath in two years and put into clean clothes. To our sorrow and shame, the sick had been badly neglected. Many had died on the beaches and on the road during their first day’s journey out of Pahlevi without being seen by a doctor.

“But at last the worst was over; we were over the hump.

“Soon we turned our attention to organising and expanding the hospital. Additional equipment and supplies were now reaching us from Baghdad and we were getting increasing help from the refugee doctors and nurses. Once again we had a few empty beds. Everyone was greatly relieved; but most of all, the officers and men of the medical regiment. We found ourselves caring for our patients with a deeper tenderness, perhaps in unconscious atonement for having neglected them so far.

“But our resources remained limited, and we made this clear in the notice we now put up at the hospital gate. In large bold letters this was our new announcement: THIS HOSPITAL IS NOT FOR THE SICK. Tucked away underneath in small inconspicuous type was the addition, ‘It is only for the very sick.’

“Soon there was news of high-level negotiations with the Russians for repatriation of the Poles still remaining in Central Asia. Then we heard of an agreement that another hundred thousand Poles would come out to Pahlevi ‘as soon as possible.’ This from the Russians, hard pressed by the Germans as they were at the time, could mean a month, a year or never. And in the meantime the medical regiment was ordered to stay at Pahlevi and wait for the second evacuation.

“Through all those months at Pahlevi there was one predominant mood and at the back of my mind, there was one constant question. The mood was a great thankfulness; my regiment had done their duty to the typhus-ridden Poles and yet not one had fallen victim to the disease. The question that clamored for an answer was the obvious one: was our savior the blind million-to-one chance, or was my father right and had God heard my cry in distress? Yet I can attempt no answer. We had taken all possible care, but in the conditions at Pahlevi, not much care was possible. We did succeed in preventing a bad epidemic, but unlike us, many Persians who had less contact with the Poles got typhus and died of it. Perhaps we were more efficient than I had thought. Perhaps I had been unduly scared and had overestimated the risk. Maybe our good army health had given us immunity. Perhaps it was not a miracle, only a miraculous coincidence.

“I remember arguing with my father once about a similar experience of his own: the cure of a young boy named Karim from the invariably fatal hydrophobia of dog bite. I was at college at the time, captivated body and soul by the beauty, the rigor and the remorseless logic of the scientific method. I was intolerant about accepting anything as true until proved in the same mathematical manner. ‘That God listens to us, that He loves us, may well be true, father,’ I had said, ‘but where is the rigorous proof?’ ‘You mean in the sense in which two and two make four?’ ‘Exactly’, I replied. ‘In that sense there is no proof. But tell me, do you believe in your parents’ love for you?’ ‘Of course, yes. What a question to ask.’ ‘But judged by the scientific method, what is the foundation for your belief in our love? We have given you much, but we have also denied your wishes, and even punished you at times. By the impersonal standards of science everything could have happened to you just the same in a commercial orphanage.’ ‘Oh, no’, shouted my heart deep down. Outwardly I remained silent, baffled by the dilemma. For against all logic, the unproven love of my parents meant all the world to me. And despite all logic I did not much care if two and two made four or made five.” (Taken from Citizens of Two Worlds, Mohammad Ata-Ullah, pp. 82-109)

Assalamo Alaikum Warahmatullah

JazakAllah kheran Al-Hakam for sharing this piece of our history which also happens to be our family history!

Masha Allah

Très belle histoire

Jazakallah pour ce partage

Jazaakallah Alhakam. This story real describe How Allah the Almighty reach human being when earnestly prayed. It indeed teach how to earnestly pray to Allah the Almighty.

غیر ممکن کو یہ ممکن میں بدل دیتی ھے

اے میرے فلسفیو زور دعا دیکھو تو

The unshakable belief in prayers can bring the Mercy of our beloved God, which turns situations into the favour of humanity.

JazakAllah for sharing.