Hazrat Musleh-e-Maud’s tireless efforts to save millions from displacement

Tahmeed Ahmad, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre

15 August 2022 marked the 75th year of independence for the South Asian nations, India and Pakistan. The many years of British rule came boiling down to just a few weeks in which the borders for these two nations were to be decided.

O. H. K. Spate states:

“In February 1947 the British Labour Government decided that the deadlock must be broken, and that the British would ‘Quit India’ by June; 1948.

“Great was the fury of old India hands; at a talk I gave later in London, an ex-governor of a Province fumed at me that grave matters which had been discussed for sixty; years were to be settled in sixty weeks and almost spat when I remarked mildly that after sixty years of talk there could not be much left to say.” (On the margins of history: from the Punjab to Fiji, p. 51)

60 later turned into six when the new deadline was moved to 15 August, giving Sir Cyril Radcliffe just six weeks to make an award regarding the boundary. Nevertheless, our sights are placed slightly elsewhere, in the small, but well-known town of Qadian.

The transfer of power

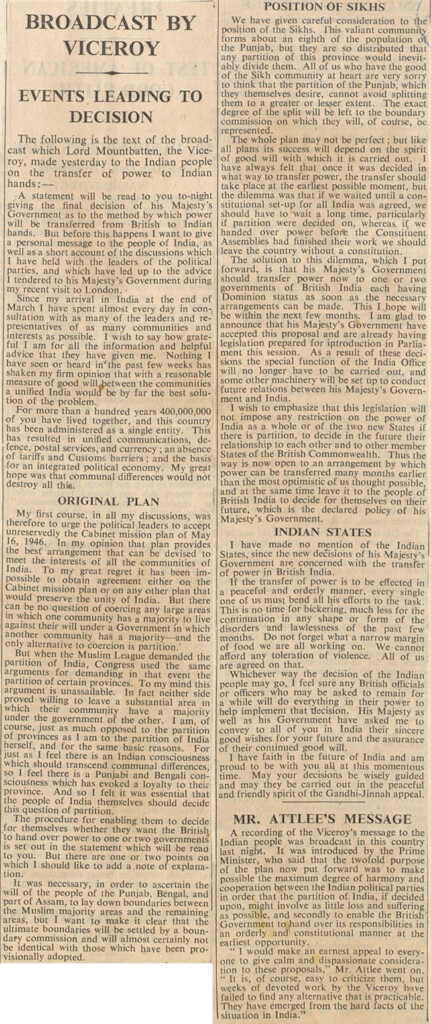

When all the possibilities and hopes for a coalition Constituent Assembly faded, officials announced on 20 February 1947 that the government wished to implement necessary plans to transfer power to the responsible people of India by June 1948.

“It is with great regret that His Majesty’s Government finds that there are still differences among Indian Parties which are preventing the Constituent Assembly from functioning as it was interned that it should. It is of the essence of the plan that the Assembly should be fully representative. His Majesty’s Government desire to hand over their responsibility to authorities established by a constitution approved by all parties in India in accordance with the Cabinet Mission’s plan, but unfortunately there is at present no clear prospect that such a constitution and such authorities will emerge. The present state of uncertainty is fraught with danger and cannot be indefinitely prolonged. His Majesty’s Government wish to make it clear that it is their definite intention to take the necessary steps to effect the transference of power into responsible Indian hands by a date not later than June, 1948.” (Hansard, HL Deb, 20 February 1947, Vol. 145, cc. 835-41)

On 3 June 1947, Prime Minister Mr Attlee stated in the British Parliament: “On 20th February, 1947, His Majesty’s Government announced their intention of transferring power in British India to Indian hands by June, 1948. His Majesty’s Government had hoped that it would be possible for the major parties to cooperate in the working-out of the Cabinet Mission’s Plan of 16th May 1946, and evolve for India a constitution acceptable to all concerned. This hope has not been fulfilled.” (Hansard, HC Deb, 3 June 1947, Vol. 438, cc. 35-46)

Independence Act

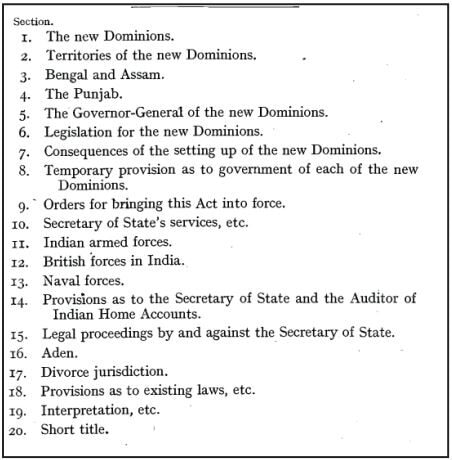

The final date came to light through the Indian Independence Act 1947: “An Act to make provision for the setting up in India of two independent Dominions, to substitute other provisions for certain provisions of the Government of India Act 1935, which apply outside those Dominions, and to provide for other matters consequential on or connected with the setting up of those Dominions. (18 July 1947)

“The new Dominions

“1. As from the fifteenth day of August, nineteen hundred and forty-seven, two independent Dominions shall be set up in India, to be known respectively as India and Pakistan.

“2. The said Dominions are hereafter in this Act referred to as “the new Dominions”, and the said fifteenth day of August is hereafter in this Act referred to as “the appointed day”. (Indian Independence Act, 1947, Chapter 30, 10_and_11_Geo_6)

The extract above is the first section of the Independence Act, but for now let’s have a closer look at the fourth section, mainly regarding the division of the Punjab:

“The Punjab

“As from the appointed day:

“(a) The Province of the Punjab, as constituted under the Government of India Act, 1935, shall cease to exist; and

“(b) There shall be constituted two new Provinces, to be known respectively as West Punjab and East Punjab.

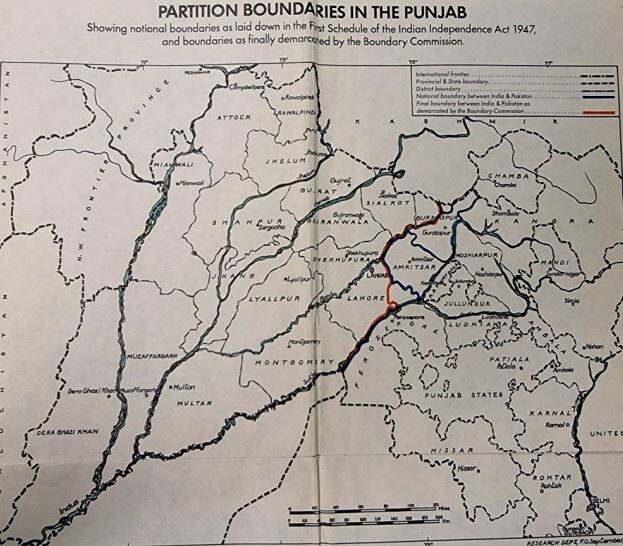

“(2) The boundaries of the said new Provinces shall be such as may be determined, whether before or after the appointed day, by the award of a boundary commission appointed or to be appointed by the Governor-General in that behalf, but until the boundaries are so determined.” (Indian Independence Act, 1947 Chapter 30, 10_and_11_Geo_6)

The umpire

One of the key issues of the Independence Act was who would be the one to divide Punjab and Bengal. India and Pakistan needed an umpire for their first and biggest game to ever take place.

One of the earliest mentions of Radcliffe comes up between Earl Listowel and Mountbatten:

“The Earl of Listowel to Rear-Admiral Viscount Mountbatten of Burma India Office,

“13 June 1947

“On receiving your telegram No. 1348-S of 7th June about the proposed Arbitral Tribunal, I at once approached the Lord Chancellor about a possible Chairman. It seems that, apart from any other consideration, the members of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council are all ruled out on account of age since 60 ought, I think, to be regarded as an absolute maximum and 55 would probably be the optimum age. […] An approach is, however, being made to Sir Cyril Radcliffe who would, I think, fill the bill admirably. ” (The Transfer of Power 1942-47, Vol. X, p. 336)

At the time they were looking for a head for the Arbitral Tribunal, whose service was needed after the partition from 6 months to two years. This tribunal would sort out any matter that came up after the partition. Many names and recommendations came and went but it was clear that the British wanted Radcliffe to be there as the head of the Arbitral Tribunal. Another idea was to get the UNO involved, but that would bring shame to the British. In other words, it would have meant they were incapable of performing their duties.

“The Earl of Listowel to Rear-Admiral Viscount Mountbatten of Burma

“20 June 1947

“I note that it was agreed at your meeting on 13th June that Patel and Liaqute Ali Khan should consider together the composition of the Arbitral Tribunal; possibly, however, the services of a distinguished outsider as chairman may still be required. You will have received my telegram number. 71 [72] about Radcliffe who, as I said in my previous letter, ought to fill the bill admirably if he is accepted. I am glad that the idea of consulting UNO about the composition of the Boundary Commissions has been abandoned and it will probably be best if a reference even to the president of the International Court of Justice is also avoided as it would inevitably involve delay.” (The Transfer of Power 1942-47, Vol. X, p. 539)

Finally, Jinnah suggested that having an Arbitral Tribunal and two different chairmen for each Boundary Commission would be a waste, so why not let the gentleman chairing the Tribunal also chair both the commissions, he said. Of course, he was unaware that Radcliffe, a man who had not even been East of Paris, was being favoured for the position. However, the damage had been done and the British had gotten what they wanted. (India Pakistan Partition Documentary BBC, www.youtube.com/watch?v=0ZS40U5yFpc )

“Record of interview between Rear-Admiral Viscount Mountbatten of Burma and Mr Jinnah.

“23 June 1947

“[…] It was suggested that in view of the fact that the Arbitral Tribunal in Mr Jinnah’s opinion would not be functioning seriously for some time, whoever was appointed Chairman of the Tribunal (and the composition of the Tribunal has not yet been agreed to by Congress) and might come out from England in the near future and act as Chairman of the two Boundary Commissions before taking over his duties with the Tribunal. He did not anticipate that the work of the Boundary Commissions would last very long. The Viceroy told Mr. Jinnah in confidence, that the man who had been suggested as Chairman of the Arbitral Tribunal was Sir Cyril Radcliffe.” (The Transfer of Power 1942-47, Vol. X, p. 581)

The Punjab Boundary Commission

Created in July 1947, the idea of the Boundary Commission was simple – there were four judges, two from the All-India Muslim League and two from the Indian National Congress. They were to review the cases brought by the various parties and then consult the head of the committee on where to draw the boundary whilst upholding all the demands.

During the partition, there were two regions where this system was used, Bengal and Punjab. Hence, two boundary commissions were made, both chaired by Sir Cyril Radcliffe. We will take a closer look at the Punjab boundary commission, which was to decide regarding Qadian, the headquarters of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community.

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community

It was clear that the Ahmadiyya Muslims had a central role to play in the partition. Whilst this was a realisation most people came to much later, Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad, Khalifatul Masih IIra had begun preparation earlier than people anticipated.

Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIra began collecting census reports from throughout the district of Punjab and other documents as well. This work was given to his brother, Hazrat Mirza Bashir Ahmadra, who was the Nazir-e-A’la of Qadian at that time. Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIra also established the “Office of the Establishment of Peace and Conciliation”. This office consisted of Hazrat Mirza Nasir Ahmadrh, Hazrat Maulvi Abdur Rahim Dardra, Hazrat Syed Zain-ul-Abideenra, Hazrat Chaudhry Fateh Muhammad Sayalra and other esteemed members of the community. This office worked tirelessly till the end of the Punjab Boundary Commission, on 31 July 1947. (Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyyat, Vol. 9)

Searching for an expert

As efforts were being made towards the partition in India, work was also being done on the other side of the world, in the heart of the Empire, the city of London. Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIra had instructed the Ahmadi missionaries in Europe and America to send any literature on boundary making and to also search for an expert.

This led Mushtaq Ahmad Bajwa Sahib, Imam of the London Mosque, to begin searching for an expert. The correspondence between him and Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIra has been recorded in Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyyat. They talked of rigorous searching for an expert, but the expenses to hire one, were not something the community could finance at the time. That was until the Imam stumbled upon Dr Oskar H K Spate, a famed Geographer from London’s School of Economics. (Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyyat, Vol. 9)

Memorandum

Coming back to India, the partition was moving at a fast pace and the question regarding who had a claim over Punjab was being made through the use of memorandums. At first, it was thought that the more memorandums the Muslim league produced, the better it would be for their case against Congress. This is why Ahmadi Muslims were told to write one memorandum separately whilst the Muslim League Gurdaspur would also write another. However, the idea was later abandoned when it became clear that only the League and Congress were to present their respective cases. Thus, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIra refrained from presenting the memorandum.

Nevertheless, when Congress gave some time to the Sikhs and the so-called “untouchables”, the League got permission for the Christians and the Ahmadis to present their separate memorandums.

One might wonder why the League put much weight on the Ahmadi case. The reason behind this is due to religious complications as much as political. The Ahrar, a Congress-supported Muslim group, had gone to extreme lengths in declaring the Ahmadis non-Muslims. This would result in Gurdaspur no longer holding a Muslim majority, hence weakening the League’s case. The Muslim League gave the Ahmadiyya Muslims the right to prepare their own memorandum so that it would be clear they wanted to join Pakistan, doing so would make Gurdaspur, if not Muslim, a League majority. (Al Fazl, 2 January 1951)

Related Content

- Hazrat Musleh-e-Maud’s services to the Muslim cause: Guiding Muslims of the Indian subcontinent amid religious and political conflicts

- The Simon Commission, First Round Table Conference and Hazrat Musleh-e-Maud’s valuable guidance

- Freedom is the birthright of everyone: Hazrat Musleh-e-Maud’s guidance regarding India’s independence and partition

- The Wavell Plan and Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad’s (ra) call for peace and India’s freedom

- The Simla Conference, 1945: Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad’s (ra) guidance prior to the conference and response to its failure

- The Cabinet Mission, 1946: Its background and Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad’s (ra) guidance

- The deadlock over Interim Government and Constituent Assembly for India: Its background and Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad’s (ra) guidance

- Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad’s (ra) services to the Muslim cause: Guidance and support to leaders of the Pakistan Movement

- May India and Pakistan live amicably: The Partition of India, 1947 and Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad’s heartfelt wish