Stanley Brush was a professor at Forman Christian College Lahore when he decided to visit Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIra in Rabwah. Many decades later, the Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre, London contacted him in 2014. He had by then settled in New Jersey, USA and was delighted to share his memories. Below is what he recalled of the visit:

Stanley E Brush, 1925-2016

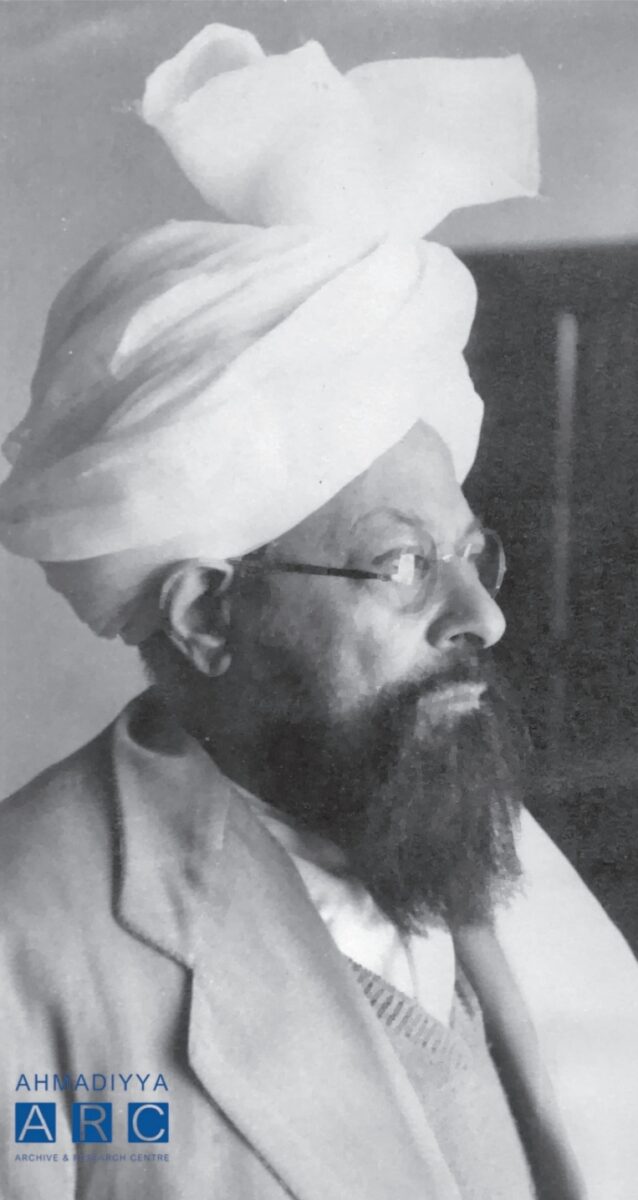

Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad, Khalifa (Caliph) of the main branch of the Ahmadiyya Movement stands by his office window at my request for a portrait photograph. He has a beard of medium length, wears wire-rimmed glasses and a pure white turban tied in the Punjabi fashion with a flare of turban fabric at the top. We are at the end of a half hour interview – the “we” being John Martin of Forman College, a US AID agricultural advisor, Bob Horton, who has provided us with a van for transportation, and me.

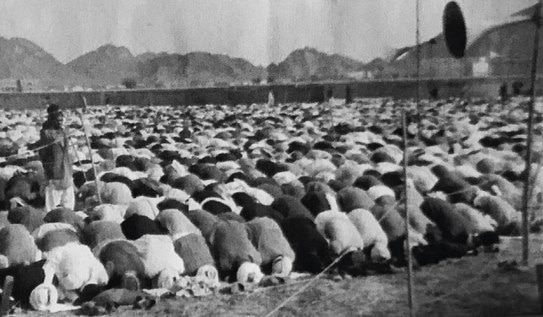

Mirza Sahib is getting ready to lead the assembled community in the noon prayer. It’s the Jalsa Salana, or Annual Convention, which is attended by Ahmadis and their guests from around the world. They are seated in rows on mats under the open sky. After the prayer, he commences an address that will go on for hours, until sunset, and the evening prayers that follow.

The interview is in English. He speaks candidly and courteously, telling us about his close relationship to God. He tells us that, while speaking, God takes control of his tongue and, when writing, God guides his pen.

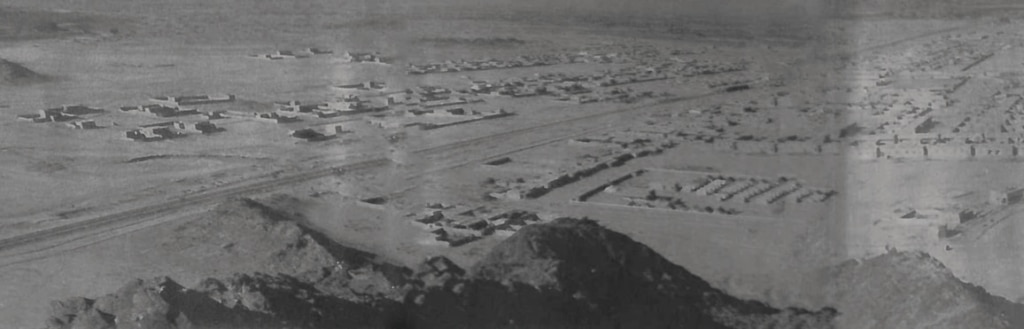

In 1947, when Sikhs drove the Ahmadis out of their home base in Qadian in the eastern Punjab, God revealed to him in a dream that their new home would be under a neela gumbad, a “blue dome.” He assumed it would be the Neela Gumbad section of Lahore, but it turned out to be the open sky of the far western Pakistani Punjab, when he learned they would not be welcome in Lahore. Here, in the barren and almost treeless wilderness, God revealed to him where to find a water source and provided the continuing inspiration for building the new Ahmadi headquarter town of Rabwah.

Some background history. The Ahmadiyya movement is one of the several reform movements that emerged from within the religious communities of the Punjab in the late nineteenth century under the heavy impact of Westerners as rulers. These movements adopted, and adapted, the organisational structures and methods of the missionary societies that arrived with the British, while reforming and defending, at the same time, their own religious communities. Some of the reformers started out as students in Christian missionary schools and were motived by that experience, rejecting “misrepresentations” of their religions while accepting the need for reform.

Ahmadiyya Islam was founded by the reformer, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, who, in a series of revelations, beginning in 1882, said that he had been granted a special mission and was, therefore, deserving of a personal oath of loyalty by his followers. He also said that Jesus did not die on the cross but survived to carry his preaching to India and is buried in Kashmir; that he, Ghulam Ahmad, was the Promised Messiah, returned, that he was the Muslim Mahdi who would conquer the world not by the sword but by argument, and that he was, also, an incarnation of Vishnu.

His Ahmadiyya Movement was officially registered, at his request, as a separate Muslim sect in 1901. It attracted substantial support, including “several men of substance and consequence,” in the words of a Punjab Government official report on the anti-Ahmadi riots of 1953. Mirza Ghulam Ahmad died in 1908. Mirza Bashiruddin Ahmad was elevated to the leadership of the community in 1918 [sic: 1914] as the Second Khalifa, “Successor.” It was then that the split with the Lahore group, who disagreed on issues of leadership and belief occurred.

Among the Ahmadi men of substance and consequence were Sir Muhammad Zafrulla Khan, the first Foreign Minister of Pakistan and President of the UN General Assembly and Dr Abdus Salam, Nobel Laureate in Physics. There were also several prominent Ahmadis in the civil administration of Pakistan and in the business community.

The theological firestorm ignited by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the founder, burst into flame in March and April of 1953. The central issue revolved around his claim to be a prophet. It was an issue exacerbated locally by vigorous proselytising among fellow Muslims, as well as a foreign missionary programme overseas. Widespread anti-Ahmadi disturbances led to the declaration of martial law in Lahore. The prime minister had refused a demand by a committee of Sunni clergy and scholars that Ahmadis be declared to be non-Muslims and that Ahmadis in office, including Sir Zafrulla be dismissed. They threatened, and then took, direct action in the streets when their demands were rejected.

Thirty-one years later, orthodoxy finally triumphed. In 1984 the Government of Pakistan under General Zia-ul-Haqq passed Ordinance XX which branded Ahmadis as non-Muslims. The community was prohibited from any public display of Islamic faith or practice or even of identifying themselves as Muslims. The gentlemanly Ahmadi head missionary in his office in Washington DC, whom I am interviewing in connection with an encyclopedia article, speaks with tears in his eyes, “In my own country I can’t call myself a Muslim.”

Faced with these difficulties, the Community moved its headquarters to London. Rabwah as a name is expunged from the map, with Chenab Nagar now its Pakistan government-mandated official name. One suspects, however, that “Rabwah” lives clandestinely in the hearts of its Ahmadi inhabitants, of whom there are several thousand. It’s certainly alive as a site on the internet, where it’s accompanied by the motto, “Al Islam: Love for All, Hatred for None.”