Malik Saif-ur-Rahman (1914-1989)

Hazrat Imam Ahmadrh was born in 164 AH. His father’s name was Muhammad and grandfather’s name was Hanbal, through whom he was called Ibn Hanbal. He belonged to the Shayban tribe, as did Muhammad bin Hasan al-Shaybani.

His grandfather ruled Sarkis, whereas his father worked at an ordinary rank in the army. Nevertheless, he was extremely generous and hospitable. He would show great hospitality to the caravans arriving from Arabia towards Khorasan.

When he moved from Khorasan to Baghdad, his financial conditions were unstable and only a short period after Imam Ahmad bin Hanbal’s birth, he passed away. Thus, Ahmadrh was raised by his uncle.

As he grew older, Ahmadrh committed the Holy Quran to memory, after which he started learning Arabic as a language. Thereafter, he began acquainting himself with the knowledge of hadith and the lives of the Companionsra and the generation that followed them.

From a very young age, Ahmadrh was extremely intelligent, modest, sensible and had an earnest desire for worshipping Allah. His favourite subjects were hadith and the lives of the Companionsra. He specialised in both these fields.

Initially, he was taught by Abu Yusufrh and in 186 AH, at the age of 22, he travelled to Basra, Kufa and the Hejaz to study hadith from world-famous muhadithin [scholars of Hadith]. It was in those travels that he met Hazrat Imam Shafi‘irh in Mecca and was deeply inspired by him. When he returned to Baghdad, he became one of his students.

He also studied Hadith from Sufyan bin Uyanah in Mecca. In Yemen, he studied the narrations of the famous muhadith Abdur Razzaq bin Al-Hammam and obtained a certificate of authority. Abdur Razzaq lived in San‘a.

Hazrat Imam Ahmadrh bin Hanbal had offered Hajj several times. On some occasions, he offered the Hajj travelling from Baghdad to Mecca on foot, whilst studying along the way. During those journeys as a student, he faced many challenges. He experienced financial problems, but always considered it secondary to the wealth of knowledge that he desired to gain. At times, he would work as a casual labourer for subsistence.

Once, when he was in Yemen and was experiencing financial difficulties, his tutor, Abdur Razzaq expressed the desire to help him financially. However, he was not prepared to accept any financial help. He would sew caps and sell them, living off the profit he made from this business.

One day, his clothes were stolen and for many days he could not leave his house. One of his fellow students, who was also a friend, got to know of this and wanted to offer him some money, which he declined. His friend persisted and asked, “How long will you remain hidden in your house? Take this as a loan and when you have the means, you may return it.” Even at this, Ahmadrh was not prepared to accept the money. Eventually, they reached an agreement that Ahmadrh would rewrite his notes neatly for his friend, and his friend would pay him in return. Thus, he purchased new clothes from that money and was able to leave his house once again.

His memory was impeccable and he had thousands of ahadith to memory. Yet despite this, he would jot down any hadith he heard and would narrate it by referring to his notes, even though he had already memorised it. He would take this precaution lest a tradition of the Prophetsa was misreported.

He studied fiqh [Islamic jurisprudence] from the jurists of the time. He studied the legal rulings of the Companionsra and the generation that followed. However, his field of interest remained hadith and the lives of the Companionsra and thus, he dedicated his whole life to learning and teaching these subjects.

Imam Ahmadrh knew the Persian language. His family had lived in Persia and as a result, the whole household was fluent in Persian.

Imam Ahmadrh as a teacher

At the age of 40, he founded a school. This was after 204 AH when his teacher, Hazrat Imam Shafi‘irh had passed away. The madrasah of hadith founded by him had gained much acclaim because alongside the lessons of hadith, Ahmad’srh taqwa, piety and good morals also had gained recognition. A large number of Hadith students was affiliated with his madrasah. Hundreds of students were always present with inkpots and pens, ready to take notes.

He survived on a meagre income, which was earned through letting properties. Some have narrated his income as being 17 dirhams a month. As has been mentioned above, he would work even as a labourer, so much so that after crops were harvested, he would go to collect fallen wheat spikes. However, he would never accept gifts from the caliphs [rulers] or the governors of the time.

Aside from ahadith, Imam Ahmadrh would not stand for views on fiqh and legal rulings to be written down and would not allow anyone else to do so. Once, someone remarked in his presence, “Abdullah bin al-Mubarak would write down views of the Hanafi fiqh.” Upon hearing this, he responded, “Ibn al-Mubarak Lam Yanzulu Minas-Samaa” meaning, “Ibn al-Mubarak did not descend from the Heavens”, and added, “Only that should be written which has come from the Heavens.”

Despite this stringent approach, his students collated his fiqh-related views, which now span many volumes.

A trial and Imam Ahmad’srh steadfastness

It was the period of religious polemic and philosophical debate. Mu‘tazila, the founders of Islamic scholasticism, were gaining a foothold. As a result, many questions being raised were: Does man have free will or is his destiny predetermined? Are God’s attributes part of the divine essence or distinct? Is speech an attribute of God? Is the Quran uncreated or created?

Debates on such topics occupied everyone. Mamun al-Rashid himself enjoyed such debates and the Mu‘tazilites would press him to extensively promote such doctrines. For this reason, the conservative scholars faced a predicament.

This brought tests for Imam Ahmadrh too. His stance was that such doctrinal debates were raised neither by the Companionsra, nor by their followers (the latter known as the tabi‘een). Accordingly, he believed that one should never take part in such debates and whatever they believed in should suffice for us too, but if one persisted, then he would inculcate that they firmly believe in the Quran being uncreated, for calling it a creation would be interpolating religion.

In his later years, however, Mamun al-Rashid’s persistence grew in that he would force people to accept that the Quran, being the Word of God, was a creation. In this state of tumult, Imam Ahmadrh and Muhammad bin Nuh were captured.

They were being taken to the court of Mamun al-Rashid in either Raqqa or Tartus when Mamun al-Rashid died. Before dying, he wrote in his will that he should be succeeded by Al-Mu‘tasim [his half-brother] and instructed that he upheld his rigid policy. Muhammad bin Nuh passed away during that journey, but Imam Ahmadrh bin Hanbal was returned to Baghdad in shackles.

After spending a few nights in a prison cell, he was taken to the new Caliph, Abu Ishaq Al-Mu‘tasim. Mu‘tasim tried his utmost and explained to him that he should accept what he claimed, but Imam Ahmadrh firmly upheld his stance. Upon seeing this, Al-Mu‘tasim became furious and ordered that he be flogged.

Due to the intensity of the whips, he fell in and out of consciousness several times, but never did he waver in his beliefs. In this manner, he remained a prisoner for 28 months, being whipped occasionally. Eventually, the regime gave up and released him.

As a result of the time he served in prison and the brutalities he faced, Imam Ahmadrh became extremely weak and for some time, he struggled to even walk. When he recovered, he resumed teaching and giving sermons.

The example of patience and perseverance that he showed during the period of trials and tribulations increased people’s respect and admiration for him. From then on, he was venerated by many.

After the death of Al-Mu‘tasim, Al-Wathiq was appointed as caliph. He too initially carried on the oppressive legacy and instructed that Imam Ahmad’srh rights of issuing religious decrees [fatwas], teaching, meeting people and remaining in that city be taken away from him. This caused him to live in hiding for some time. In his later years, Wathiq became tired of the rigid policies as debates on the Quran being a creation started becoming ludicrous.

Once, a jester entered Wathiq’s royal court saying, “I have come to offer my condolences, because what is a creation must one day face death. And if the Quran dies, then how will we offer Tarawih prayers?” Wathiq exclaimed at him, and said, “You fool! How can the Quran die!”

When a scholar was once arrested and brought before Wathiq, Ahmad bin Abi Daud, a leading proponent of the Mu‘tazilites was also present. The scholar asked Ibn Abi Daud, “Did the Holy Prophet, peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, and his Khulafara not know about the debate surrounding the creation of the Quran? If they did and chose to remain quiet, then we should follow suit. But if, God forbid, they were ignorant and unaware of this issue, then O ignoble man, how do you deem yourself a scholar?”

Upon hearing this, Wathiq sprang up in wonder and repeated the sentence over and over, reproaching Ibn Abi Daud. Wathiq released the trouble-stricken scholar and lauded him.

Thus, through their perseverance and patience, Imam Ahmadrh and other such scholars closed the debate around the creation of the Quran altogether. After approximately 14 years of commotion and agitation, the conditions became peaceful once again. The creation of the Quran debate was, in fact, nothing more than a war of words drenched in prejudice and bias. But after a long time of debating, the outcome was that as far as the knowledge of God was concerned, the meanings of the Quran had always existed, but its words, i.e. the letters and phonics, were created when the Holy Prophetsa heard them from Gabriel and the Companionsra heard them from the Holy Prophetsa, who then passed them on to the whole Muslim Ummah, who then recited them regularly.

Al-Mutawakkil succeeded Wathiq and completely abandoned the old rigid policies. He removed the Mu‘tazilites from the royal court and instead desired the pleasure of the jurists and muhadithin. In this manner, he reinstated the law and order of the nation.

Imam Ahmadrh specialised in hadith and fiqh. Alongside his pleasant appearance, he embodied the highest orders of patience, perseverance, courage, meekness, taqwa and purity. His lessons would capture the hearts of promising students.

When he passed away at the age of 78 in 241 AH, the whole of Baghdad went into mourning. Hundreds of thousands of people flocked for his funeral and felt as though a great imam had departed them.

Imam Ahmad’s fiqh-related views

His views on doctrines and politics always remained in conformity with the venerated Muslims scholars of the past. His belief was that the straightforward principle was to adhere to the Quranic elucidations and whatever can be proven through ahadith, that should suffice.

In terms of politics, he considered the obedience of rulers of the time as mandatory and to raise the sword against them as strictly prohibited because the sword disturbs the general law and order and control. On the other hand, when appropriate, there should be no shortage in promoting righteous deeds, preventing wrong, suggesting alternative solutions and speaking the truth, as these are also mandatory.

Imam Ahmadrh was a leading scholar in hadith and an Islamic jurist, however some scholars have denied that he was ever a jurist.

Imam Jarir Al-Tabari wrote a book on Ikhtilaf al-fuqaha [disputes among Islamic jurists] in which he left out mentioning Imam Ahmadrh, which resulted in questions being asked. His response was that Imam Ahmadrh was a muhadith, not a jurist, and for this reason, he left him out. This resulted in fury spreading among the masses. Ibn Jarir’s house was stoned and he escaped with great difficulty.

Despite all this, a large collection of Imam Ahmad’srh fiqh-related views and religious verdicts is accepted among the Hanbali school and there is no credible reason to deny its authority. However, what is true is that his fiqh-related views were inspired by his knowledge of hadith and the views of the Companionsra.

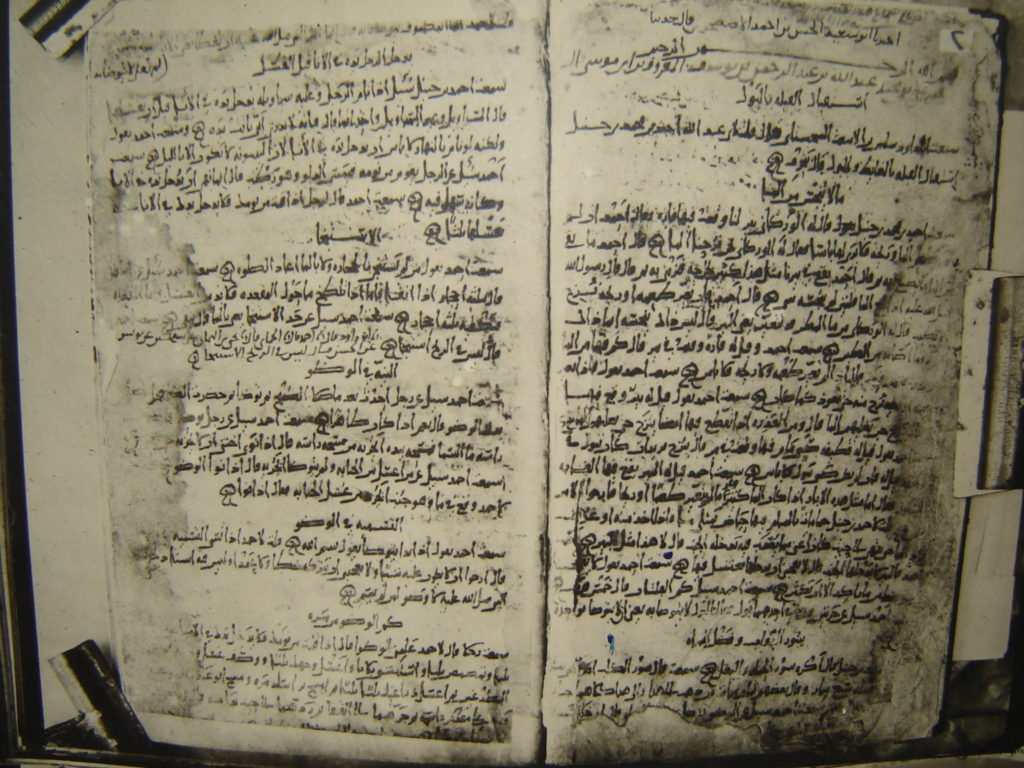

Musnad Imam Ahmad

His monumental service to hadith is preserved in the form of his magnum opus, Al-Musnad. The book contains between 30,000 to 40,000 ahadith and narrations of Companionsra. His book was considered a foundation for future muhadithin.

Imam Bukharirh, Imam Muslimrh and other acclaimed muhadithin referred to this book while preparing their compilations, and in selecting authentic ahadith, they got considerable help from it.

Instead of focusing on the subject-matter, the Musnad lists ahadith in order of narrator. For example, first are the ahadith narrated by Hazrat Abu Bakrra, followed by ahadith narrated by Hazrat Umarra, then by Hazrat Uthmanra, and in this manner, all the Companions’ra narrations have been compiled.

There have been efforts to collate the narrations of Musnad subject-wise but have not been published in its complete form as of yet.

No doubt, there are some ahadith that are weak in the Musnad, but scholars have elucidated that there are no fabricated traditions in the Musnad. Imam Ahmad’srh belief was that after the Quran and Sunnah [practices of the prophetsa], hadith is one of the sources of Shariah, regardless of whether the traditions are authentic, weak, have narrators omitted in the chain of narrators or have a continuous chain of narrators.

He considered the sayings of the Companionsra as an authority and would cater for the views of the tabi‘een [those that followed the Companionsra]. When necessary, albeit rarely, he would rely on qiyas [deductive analogy], istislah [seeking the best public interest] and istiswab [seeking consultation]. He did not believe in the lawfulness of any other ijma‘ [concencus] other than the consensus of the Companionsra. In his opinion, the concept of a general consensus was incorrect as there could have been opponents among them who the people were not aware of.

According to the Hanbali school of thought, it is necessary to carry out qiyas in the absence of a decisive dictum. However, in their opinion, the meaning of qiyas is vast as compared to the Hanafi and Shafi‘i schools of thought. It includes all the means of deduction i.e. istihsan [application of discretion in a legal ruling], masalih-e-mursalah [a consideration that secures benefit and prevents harm] and istishab [logical reasoning through the presumption of continuity]. For example, according to the Hanafis, the validation of bay‘ salami [sale agreement by advance payment] is contradictory to qiyas as it is against the decisive doctrine of:

لا تبع ما لیس عندک

“Do not trade with that which you do not have”, and it falls under the category of bay‘ al-ma‘dum [sale of non-available goods], whereas in view of the Hanbalis, the legitimation of this sale’s agreement is based on qiyas because it has been permitted by keeping in view the interest, demand and custom of the public.

For the public interest, Imam Ahmadrh saw it permissible to deport malicious and disorderly elements and to compulsorily reside the needy in people’s homes when there was no other solution. The same applies to forcing someone to learn a skill when no one in that profession is available.

Thus, the Hanbali school is no less in favour of using a medium, but it discourages the usage of a medium when the outcome can lead to disorder. People with contagious diseases can be discouraged from visiting public places. In times of public disorder and unrest, the buying and selling of weapons can be halted. Talaqqi al-Rukban [manipulative trade, where a city dweller buys goods from a villager for a small price and sells it at a much higher price, exploiting the villager’s ignorance] is, for this reason, considered an illegal practice.

In this regard, the intention and the outcome will come into play. For instance, if a person shoots their gun at a person with the intention of killing them, but instead of the bullet hitting the intended target, it kills a snake, then although the outcome may be considered good, in reality it was ill-intended. In the sight of Allah, such a person would have sinned and they may be summoned in this world also.

If a person imprisons another in their home and as a result, the captive dies of starvation and thirst, in Imam Ahmad’srh view, the captor would have to pay compensation. To let one’s apartment for dance parties is, under the aforementioned condition, considered prohibited.

The Hanbali school has sought immense help from istishab. Under this principle, their belief is that doubt cannot end certainty. For example, water is pure and until there is certainty that it has been contaminated, it will be deemed pure and any doubt will be shunned.

The advancement of Imam Ahmad’s beliefs

The beliefs of Imam Ahmadrh have become widely accepted by means of his followers, alongside his books. Imam Ahmad’srh son, Abdullah, gave much publicity to his famous work Al-Musnad. Similarly, his students, including Abu Bakr al-Athram, Abdul Malik al-Maimuni, Abu Bakr al-Maruzi, Ibrahim bin Ishaq al-Harbi, Abu Bakr al-Khalal and many others of his outstanding students spent their lives devoted to spreading his doctrines.

Scholars by the likes of Imam Ibn Taymiyyah and Imam Ibn al-Qayyim were affiliated with his school of thought.

The Hanbalis deem ijtihad [the process of making a legal decision in Islamic law by independent interpretation of legal sources] necessary in every age and believe its door to be open. Although Islamic thought flourished, disputes began to soar. Every new mujtahid [the one who applies ijtihad] began to acquire their own legal stand in a given issue and there was never a conclusion to such matters.

The scholars of the Hanbali school were stalwarts in the intellectual circles, but despite this, they were not able to make the Hanbali school widely acceptable.

There were many reasons for this, for instance, other beliefs of fiqh had more of a footing and the Hanbali school was never adopted in previous times as the state religion. Now, however, it is the state religion in Saudi Arabia.

For various reasons, oppression, violence and prejudice have been prevalent among the Hanbalis. The followers of the Hanbali school were harsh on the public and would not desist from creating disorder. A short period before the Tatar attack, Baghdad and the areas in close proximity were engulfed in rebellious disturbances and uproars. For this reason, people generally began to abhor the Hanbali school.

(Translated by Al Hakam from the original Urdu in Tarikh Afkar-e-Islami, authored by Malik Saif-ur-Rahman Sahib)