Abu Hamdan, Pakistan

Khost, Afghanistan was the city in which Sahibzada Abdul Latif Shaheedra was born. His birth-place was in a village called Syed-gah. His family genealogy belonged to the sacred saint Hazrat Ali Hajverirh, commonly known as Data Ganj Bakhshrh, whose tomb is situated in Lahore, Pakistan. Hazrat Sahibzada Abdul Latif ’sra ancestors may have moved from Iran to Saharanpur (India) and thereafter moved to Syed-gah. (The Martyr, Hazrat Sahibzada Abdul Latifra by Khuddam-ul-Ahmadiyya USA, p. 80)

The family was very well established in Afghanistan, possessing around 30,000 acres of land. (BA Rafiq, The Afghan Martyrs, The tragic tale of the first martyrs of Ahmadiyyat in Kabul, Afghanistan)

Hazrat Sahibzada Abdul Latifra was an eminent scholar and academic of his times undoubtedly. A learned scholar of the Quran, hadith, Islamic jurisprudence and a man who deeply understood the philosophies of religion. As a very well established and accepted scholar, he would be the judge of disputes amongst his locality and was considered a credible figure in Afghanistan. His followers and students numbered up to 50,000 (Frank A Martin, Under the Absolute Amir).

He would often travel to India for the pursuit of knowledge and he happened to visit Amritsar and stayed there for around three years, learning hadith. On another journey, he travelled to Lucknow, India and studied under many great scholars of his time. (Ibid)

After studying with the renowned scholars of India and returning to Syed-gah, Hazrat Sahibzada Sahibra soon became quite famous due to his spiritual and logical approach towards Islamic teachings. The amir of Afghanistan always graded him with honour and respect. At one occasion, the amir expressed, “I wish there were one or two other scholars like you in Afghanistan.” (The Vernacular Newspapers of Punjab,1903)

Other than the amir, there were numerous renowned persons among the Afghans who were from among his students. One of them was the Governor of Khost Province, Shirindil Khan. Shirindil was a paternal uncle of the Amir, Abdur Rahman. He also had great love and respect for Hazrat Sahibzada Sahibra and on many expeditions, he kept him close-by for consultation and guidance.

Martyrdom

The honoured Sahibzada Abdul Latif Shaheedra accepted Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the Promised Messiah, peace be upon him, and was brutally martyred due to his firm faith in him. The book, Peaceful Conqueror of Baluchistan ascribes his martyrdom to the beliefs of Hazrat Ahmadas, which Abdul Latifra accepted and supposedly would injure the political spectrum of Afghanistan:

“… if his preaching was listened to, it would upset Muhammadenism and as he preached that Mussalmans must regard Christians as brothers and not as infidels, this would render useless the Amir’s chief weapon, Jihad [religious war] in case of English or Russian aggression.” (Sir Robert Groves Sandeman, Peaceful Conqueror of Baluchistan, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge)

In turn, Hazrat Sahibzada Sahibra was imprisoned at Kabul. The amir himself could not find anything wrong with him, nor did his brother Nasrullah Khan ever. Nevertheless, “a jury of twelve of the most learned moullahs was convened, and even their examination of the accused elicit nothing”. (Iftikhar Ahmad Yousafzai and Himayatullah Yaqubi, The Durand Line: Its Historical, Legal and Political Status)

However, the amir again sent him to the “mullahs” (Muslim religious clerics) saying that they should sign an edict (fatwa) declaring him an infidel and worthy of death. Again “the majority of the moullahs made affirmation that he was innocent of anything against their religion but two of the moullahs” gave their verdict against him and so, he was stoned to death. Many newspapers published this tragic news about the murder of this innocent soul. Some of them include the following:

Punjab Samachar, Lahore, 15 August 1903

“Some time back, Mulla Latif, who owned a jagir in the Bannu district and had considerable influence with the amir, prepared to start on a pilgrimage to Mecca and received 1,000 rupees from Habibullah Khan towards the expenses of the journey. After leaving home, however, he went to Qadian, where his feelings were so worked upon by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad that he gave up the idea of going to Mecca and decided to become a preacher of the Ahmadi faith. When the amir heard of this, he sent for the mullah and gave him to understand that the Mirza’s followers had been driven out of the pale of Islam, with the ulema of Mecca and Medina having issued fatwas to that effect. The man was given some time to rectify the mistake committed by him; but he would not change his mind in the belief that ‘the Promised Messiah’ would avert any coming injury.”

The Sialkot Paper, 7 September 1903

“About the tragic end of Mulla Abdul Latif of Ghazni … that the following two questions naturally suggest themselves on hearing the sentence passed against the Mulla:- Is it right to kill an innocent person? Should change of religion be punished with death? The Editor then proceeds to remark that the subjects of the British Government enjoy perfect liberty in the matter of religion. It does not stone to death or blow from guns those who profess other than the State religion. Not infrequently, vernacular papers indulge in scurrilous and unbecoming remarks against Jesus Christ, yet the Government never punishes the offenders in this respect with a sentence of death. There is, however, nothing surprising in the despotic Government of the Amir punishing heresy in so terrible a manner. The writer concludes by remarking that the above reasons lead him to pray for the stability of British rule.”

Siraj-ul-Akhbar, Jehlum , 24 August 1903

“A respectable family of Sahibzadas, who own some land in the Bannu District, had settled at Khost in Afghanistan during the time of the late Amir Abdur Rahman. One of the members of this family, Maulvi Abdul Latif, aft er receiving his religious education in India, represented the Afghan Government in the last Boundary Commission and was subsequently appointed Chief Maulvi at Kabul. Last winter, the Maulvi left his home, with the permission of Amir Habibullah Khan, to go on a pilgrimage to Mecca. Instead, however, of proceeding to the holy city, Maulvi Abdul Latif went to stay at Qadian with Mirza Ghulam Ahmad and became his disciple. On his return home, aft er a lapse of two or three months, the Maulvi sent the Mirza’s writings, together with his own views on them, to Sardar Nasarullah Khan for perusal. The step brought a squad of 12 soldiers from Kabul to convey him [news] for trial before the Afghan Maulvis for heresy. The latter, failing to persuade Abdul Latif to recant his religious beliefs, sentenced him to be stoned to death. The deceased’s family also has been conducted to Kabul under arrest, their personal effects being confiscated to the State.”

Fulfilment of prophecies

“Before being led away from the Amir’s presence to be killed, the moullah prophesied that a great calamity would overtake the country.” (Tales of Travel, Marquess Curzon)

So, the day he was stoned to death, that very night at 9pm, a great storm appeared with violence and lasted up to half an hour. It was quite unusual, “so the people said that this was the passing of the soul of moullah”. This was then followed by the cholera outbreak and “this was also regarded as part of the fulfilment of the moullahs’ prophecy”. And the amir and the prince started fearing due to this. The cholera outbreak and the amir’s reaction was reported by eminent newspapers as well. The Civil and Military Gazette reported:

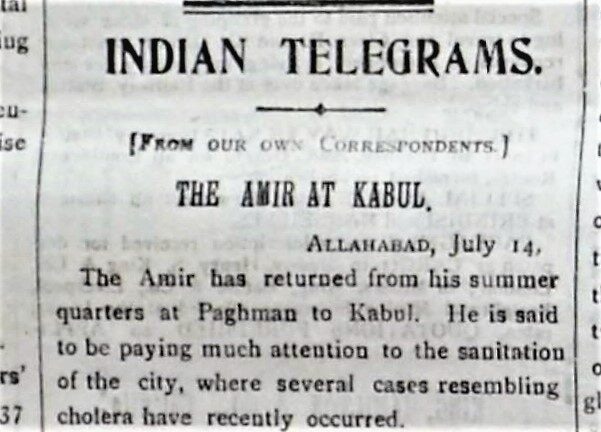

“The Amir has returned from his summer quarters at Paghman to Kabul. He is said to be paying much attention to the sanitation of the city, where several cases resembling cholera have recently occurred” (Civil and Military Gazette, 16 July 1903)

Later that month, the paper noted, “Cholera continues prevalent in Eastern Afghanistan. The Afghan Government has established quarantine stations to endeavor to keep it out of Kabul. The Amir is still in Kabul but has kept his family to his summer residence at Paghman” (Civil and Military Gazette, 28 July 1903)

Durand Line Agreement

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, Afghan officials were quite concerned about their external borders, starting from its border with Russia. After the successful settlement of Russo-Afghan borders, Amir Abdur Rahman turned his focus towards the Indian border. For this he writes to the British officials, “Having settled my boundaries with all my other neighbours [Persia, China and Russia], I thought it necessary to set out the boundaries between my country and India, so that the boundary line should be definitely marked out around my dominions, as a strong wall of protection.”

General Roberts

As a result of this, in 1892, the then Viceroy of India appointed General Robert to go to Kabul for the settlement. But the amir was not happy with the appointment of General Robert, as “He considered him a hardliner general because of his role in large scale massacre during the second Anglo-Afghan war. The memories of the Afghans’ defeat at his hand were still fresh in their minds.”(Iftikhar Ahmad Yousafzai and Himayatullah Yaqubi, The Durand Line: Its Historical, Legal and Political Status)

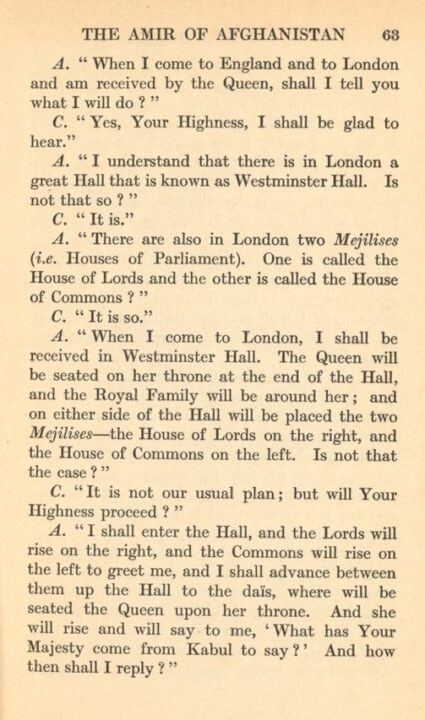

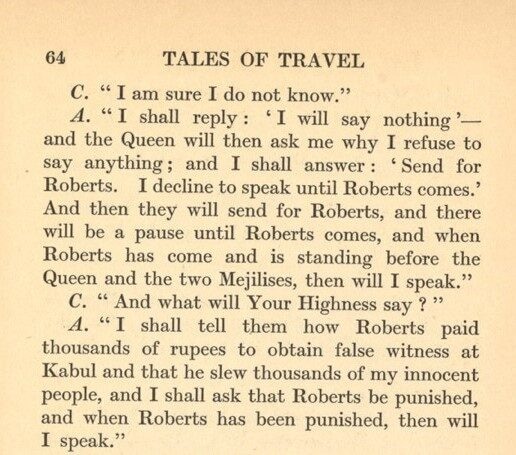

The amir had a very satirical conversation about General Robert with the next Viceroy of India, Curzon (1898- 1905) upon his visit to Kabul in 1895. Her Majesty the Queen had invited the amir to pay a visit to Great Britain, and the dialogue between both the Amir and Curzon can be read in the images below. (Tales of Travel, Marquess Curzon)

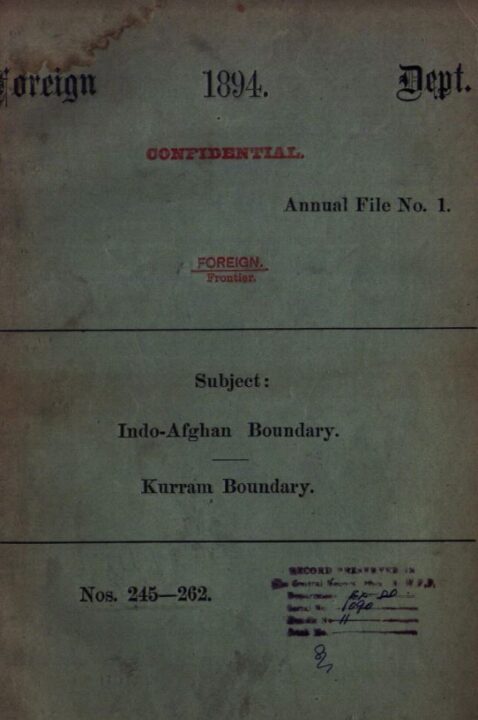

In 1893, Sir Mortimer Durand, a secretary of the British Indian government, was appointed for the aforementioned boundary settlement with Afghanistan.

The agreement took place between Durand and Abdur Rahman Khan, the Amir, or ruler, of Afghanistan. It was signed on 12 November 1893 in Kabul. A 1,640-mile border was supposed to be demarcated.

SM Durand

It was an effective agreement; “the misunderstandings and disputes which were arising about these Frontier matters were put to an end, and aft er the boundary had been marked out according to the above-mentioned agreements by the Commissioners of both governments, a general peace and harmony reigned which I pray God may continue forever’. (“The Pathans”, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts)

After the agreement was signed, formal commissions were formed from either sides.

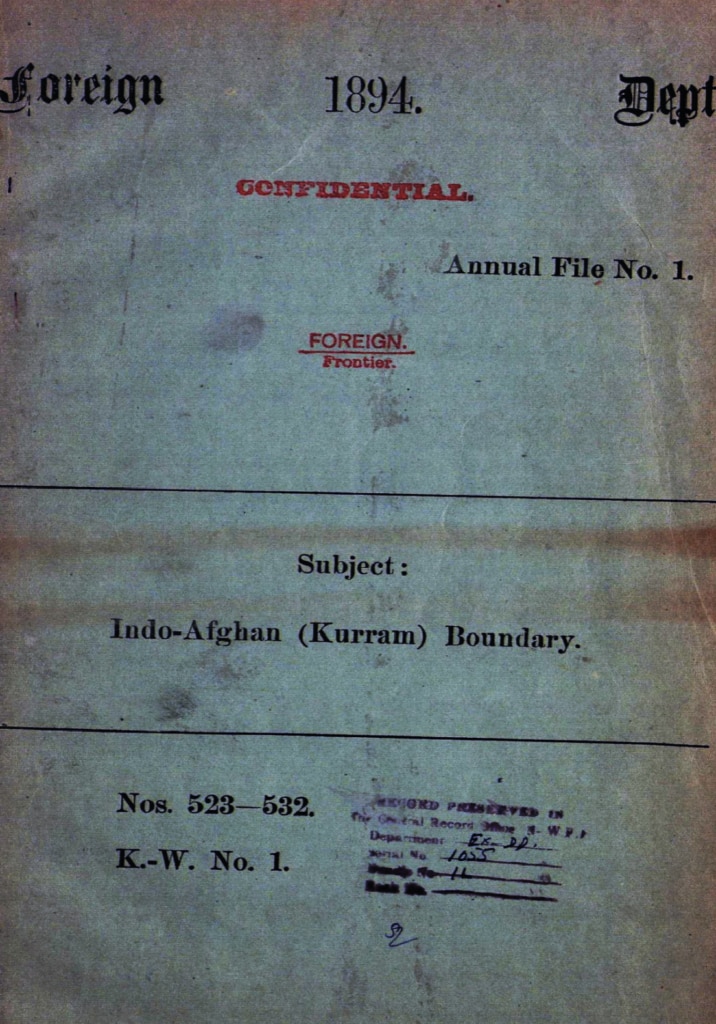

Boundary Commissions

The British were represented by Sir Mortimer Durand and Sahibzada Abdul Qayyum of Topi, a political agent of the Khyber Agency on behalf of the British Viceroy and Governor General. In addition to these two, there were some other names involved in this demarcation, which included:

- JS Donald CIE, Officer on Special Duty Kurram

- Commissioner and Superintendent, Peshawar Division

- CL Tupper Chief Secretary to Government of Punjab

- Said Shah, (Probably Syed Chan Badshah), to build a pillar at Lora Khula

- Lieutenant Colonel JB Hutchinson Commissioner

- Superintendent Derajat Division.

- HA Anderson

- L White King

- Captain Macmahon

- Babu Hira Singh

The Afghan side was represented by a former governor of Khost Shirindil Khan and Sahibzada Abdul Latifra, who was a very close and trusted agent of the governor and amir.

Some other names involved in the demarcation from the Afghan side were:

- Dad Muhammad Khan Hakim of Chakmannis

- Muhammad Amin Khan

- Kiramat Khan

- Mir Afzal Khan

- Khwaja Mir Khan

- Pir Muhammad Khan Daff adar

- Malik Ghulam Muhammad

- Najam ul Din

- Ghulam Haider Khan (appointed by the amir to demarcate beyond Peiwar Kotal)

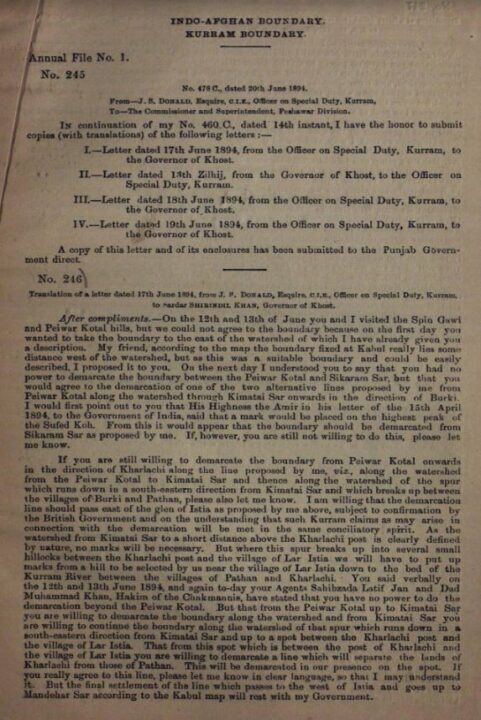

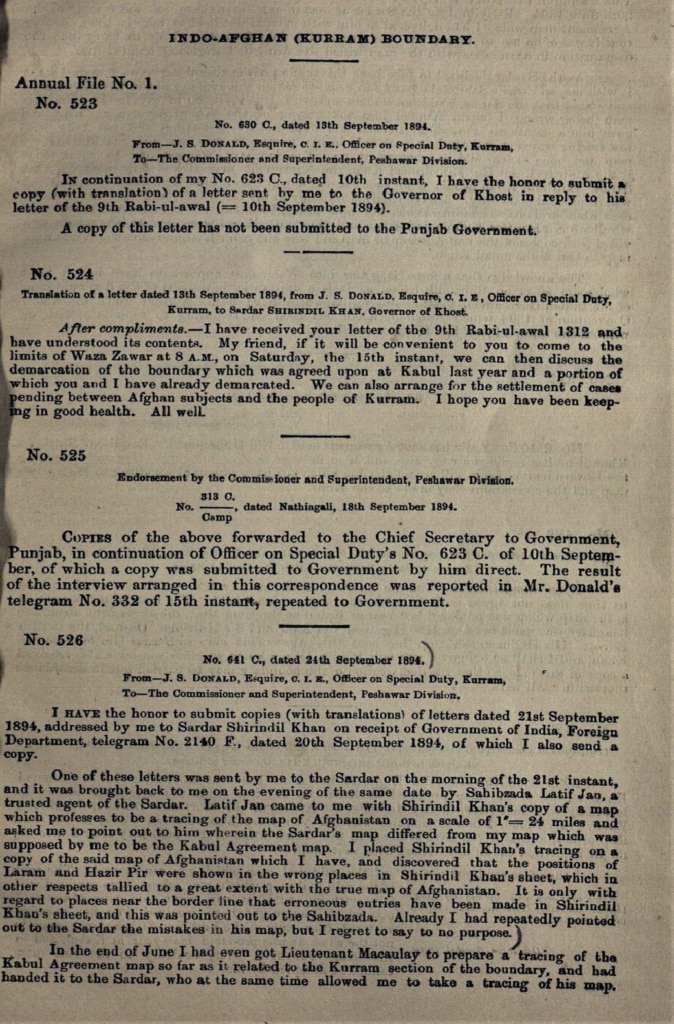

Some official correspondence (telegrams) of the Durand Line demarcation show that there had been many disputes during the demarcation process, mainly because of the wrong marking of the demarcation areas. Sometimes, it was the wrong marking and most of the times, it appears to be the language barrier (while translating from English to Persian/Dari and vice versa).

A trusted agent

While talking about an issue regarding the Kharlachi Dam, the British Officer, JS Donald wrote to Shirindil Khan, the Governor of Khost, dated 17 June 1894:

“You said verbally on the 12th and 13th June 1894 and again to-day your agents Sahibzada Latif Jan and Dad Muhammad Khan, Hakim of the Chakmannis, have stated that you have no power to do the demarcation beyond the Peiwar Kotal”

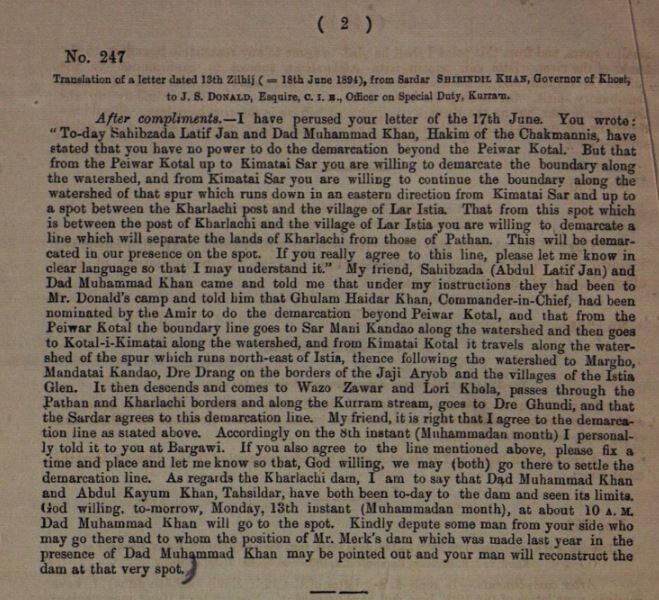

Shirindil replied on 18 June 1894:

“My friend Sahibzada (Latif Jan) and Dad Muhammad Khan came and told me that under my instructions they had been to Mr Donald’s camp and told him that Ghulam Haider Khan Commander In Chief had been nominated by the Amir to do the demarcation beyond Peiwar Kotal”

Dispute about the originality of maps

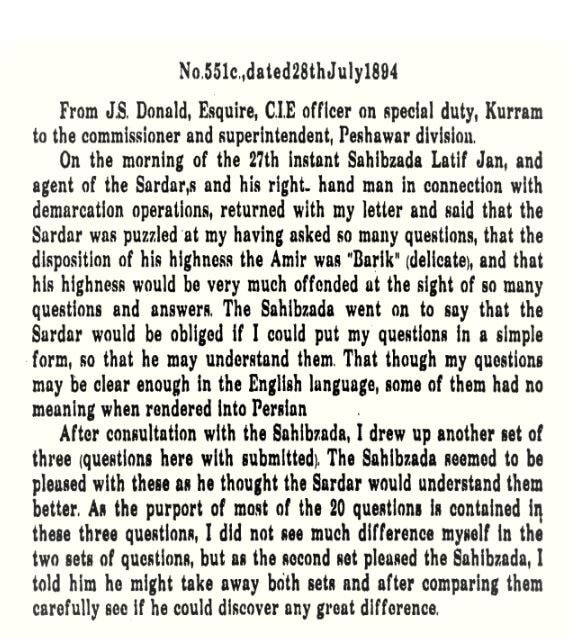

On 28 July 1894, JS Donald wrote to Shirindil Khan:

“On the morning of the 27th instant Sahibzada Latif Jan, and agent of the Sardar’s and his right-hand man in connection with demarcation operations, returned with my letter and said that the Sardar was puzzled at my having asked so many questions, that the disposition of his highness the Amir was “Barik” [delicate], and that his highness would be very much offended at the sight of so many questions and answers. The Sahibzada went on to say that the Sardar would be obliged if I could put my questions in a simple form, so that he may understand them. That though my questions may be clear enough in the English language, some of them had no meaning when rendered into Persian.

“After consultation with the Sahibzada, I drew up another set of three [questions that were submitted]. The Sahibzada seemed to be pleased with these as he thought the Sardar would understand them better. As the purport of most of the 20 questions is contained in these three questions, I did not see much difference myself in the two sets of questions, but as the second set pleased the Sahibzada, I told him he might take away both sets and after comparing them carefully see if he could discover any great difference.”

On 24 September 1894; the British Officer JS wrote again to Shirindil Khan, the Governor of Khost:

“I have the honor to submit copies (with translations) of letters dated 21st September 1894, addressed by me to Sardar Shirindil Khan on receipt of Government of India, Foreign Department, telegram No. 2140 F., dated 20th September 1894, of which I also send a copy.

“One of these letters was sent by me to the Sardar on the morning of the 21st instant, and it was brought back to me on the evening of the same date by Sahibzada Latif Jan, a trusted agent of the Sardar. Latif Jan came to me with Shirindil Khan’s copy of a map which professes to be a tracing of the map of Afghanistan on a scale of 1″=24 miles and asked me to point out to him wherein the Sardar’s map differed from my map which was supposed by me to be the Kabul Agreement map. I placed Shirindil Khan’s tracing on a copy of the said map of Afghanistan which I have, and discovered that the positions of Laram and Hazir Pir were shown in the wrong places in Shirindil Khan’s sheet, which in other respects tallied to a great extent with the true map of Afghanistan. It is only with regard to places near the border line that erroneous entries have been made in Shirindil Khan’s sheet, and this was pointed out to the Sahibzada. Already I had repeatedly pointed out to the Sardar the mistakes in his map, but I regret to say to no purpose.”

He further added:

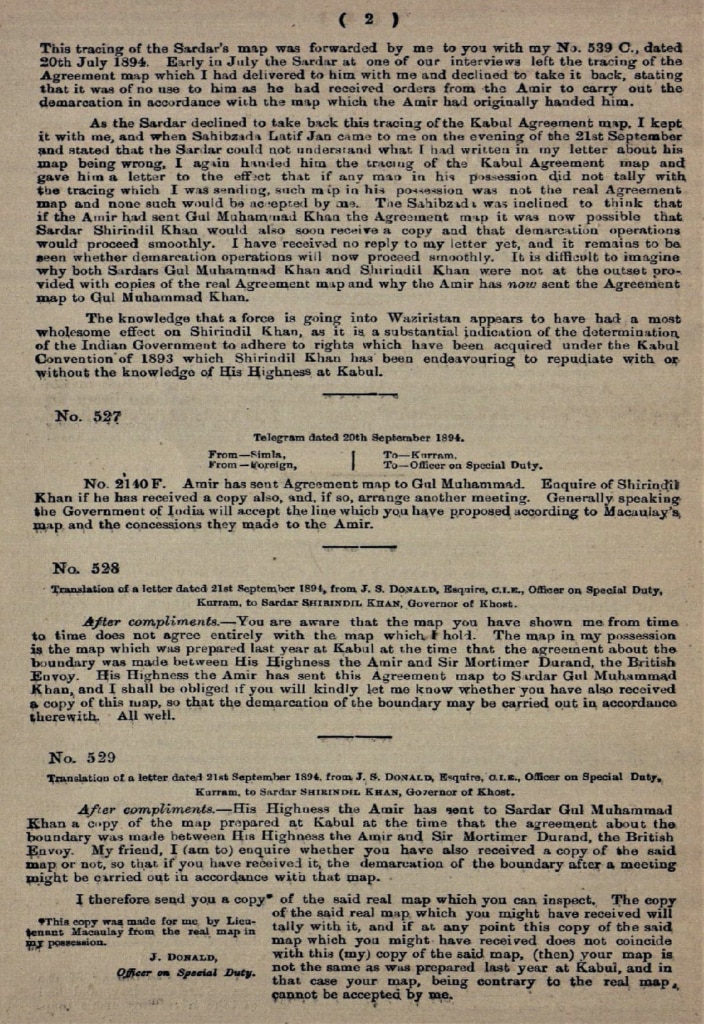

“As the Sardar declined to take back this tracing of the Kabul Agreement map, I kept it with me, and when Sahibzada Latif Jan came to me on the evening of the 21st September and stated that the Sardar could not understand what I had written in my letter about his map being wrong, I again handed him the tracing of the Kabul Agreement map and gave him a letter to the effect that if any map in his possession did not tally with the tracing which I was sending, such map in his possession was not the real Agreement map and none such would be accepted by me. The Sahibzada was inclined to think that if the Amir had sent Gul Muhammad Khan the Agreement map it was now possible that Sardar Shirindil Khan would also soon receive a copy and that demarcation operations would proceed smoothly. I have received no reply to my letter yet, and it remains to be seen whether demarcation operations will now proceed smoothly. It is difficult to imagine why both Sardars Gul Muhammad Khan and Shirindil Khan were not at the outset provided with copies of the real Agreement map and why the Amir has now sent the Agreement map to Gul Muhammad Khan. The knowledge that a force is going into Waziristan appears to have had a most wholesome effect on Shirindil Khan, as it is a substantial indication of the determination of the Indian Government to adhere to rights which have been acquired under the Kabul Convention of 1893 which Shirindil Khan has been endeavoring to repudiate with or without the knowledge of His highness at Kabul.”

Conclusion

From the above correspondence, it is quite evident how Sahibzada Abdul Latif Sahibra was a trusted official of the amir and a faithful native, who had remained at the forefront in advocating for his country in front of British officers. It is also clear that the British officer as well as Sardar Shirindil Khan were clearly endorsing and glorifying his zeal and efficiency in this regard.

Unfortunately, his trustfulness and loyalty could not conquer the enmity and hatred which had been developed in the amir. The amir knew well it was a mistake.

The consequences that occurred thereafter, the situation in which all the culprits of this murder were punished by the Almighty and how the words of the Promised Messiahas were fulfilled are accounts that should be published on a separate occasion.

Complete research and documents pertaining to this article

The article is an absolute compilation of historic events. An absolute gem! Thank you AlHakam!

Amazing!

Thank you alhakam!

It is good effort

But not enough.

Thank you so much for summarizing the historical events about Sahibzada Abdul Latif Sahib and the Durand Line. The rest is safe (in original detailed forms) in relevant books and documents.