Fazal Masood Malik and Farhan Khokhar, Canada

The value of ihsan is deeply rooted in the teachings of Islam, binding the very fabric of its existence. It can be defined as “kindness” or “benevolence”, though the precise understanding of the term is more complex than what translation credits. The Holy Prophet Muhammad, peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, was a living example of ihsan.

From the obedience of Allah, selfless service to humans and kindness to animals, it can be indeed said that he epitomised the state of excellence in ihsan.

Before prophethood, his profound vocation for human welfare can be witnessed in the fact that he became known as the “amin” and “sadiq” (honest and truthful), in addition to entering a pact known as Hilf-ul-Fuzul or “Confederacy of Rights”. The agreement was entered and honoured by a few members of the Quraish tribe, who recognised the fault in society and wanted to establish the social welfare that was much needed.

Even after his divine appointment, the Holy Prophetsa would remember this pact with fondness and honour it. The Holy Prophetsa was always viewed as a leader with exceptional unifying force; this view was held before the ministry and can be witnessed exponentially after prophethood. Whether it was keeping the peace during the rebuilding of the Ka‘bah or ensuring fair treatment of traders in Mecca, Muhammadsa was called upon to ensure justice through wisdom was dispensed.

Although no Muslim state existed in Mecca, people who joined the fold of Islam sought guidance from the Holy Prophetsa for their religious and worldly needs. His treatment of people, an extraordinary sense of justice and societal well-being preceded him. An example of his virtues with respect to a neighbour demonstrates his humbleness.

Whenever the Holy Prophetsa would depart from his abode, a neighbour would take the opportunity to express their displeasure by dumping garbage onto his holy being. One day, the usual encounter seized. Concerned for their well-being, he sought permission to enter their premises. The neighbour was stunned and enquired what business had brought him there, to which the Holy Prophetsa replied with obvious concern that he wanted to ensure the well-being of the neighbour as their usual encounter did not occur.

Needless to say, that was the end of such abusive behaviour towards a man of mountainous stature! Those who heeded to his call and professed belief in the One God were severely persecuted in Mecca.

Once the persecution in Mecca became unbearable, the Holy Prophetsa migrated to Yathrib (later Medina). Medina was a stateless entity, where existed many tribes, but no central command of any size.

Once the state of Medina was formed, a system began to develop. With scant revenues and mounting needs of an infant society, the concept of Bait-ul-Mal (treasury) came into being.

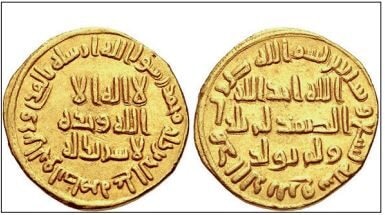

One of the revenue sources of Bait-ulMal was Zakat, which became mandatory in 2 AH. Bait-ul-Mal, in its infancy, was a depositary where money and goods were temporarily placed, pending distribution. It would remain so until Hazrat Umarra established a diwan in 20 AH to address the increase in revenue and the nation’s financial needs. Bait-ul-Mal, coupled with diwan, marked the start of the Islamic state treasury.

While the Holy Quran gave much freedom to the establishment of income for the state, it provided specific guidance where this money should be spent. The core of Islamic teaching is that the wealth “should not circulate only between the wealthy” (Surah al-Hashr, Ch.59: V.8).

Over the course of 22 years, where the Holy Quran was revealed, the guidance on the welfare of society was established, with the key points being (Surah al-Taubah, Ch.9: V.60; Surah al-Hashr, Ch.59: V.8-11):

1. Eliminate poverty and bridge the gap between the rich and the poor

2. Ensure fulfillment of the basic needs of every citizen, regardless of their faith or gender

3. Help those who are at risk of falling into error

4. Freeing of slaves and those struggling under loans

5. Helping anyone affected by calamity or struck by tragedy

During the life of the Holy Prophetsa, the primary sources of income for Bait-ul-Mal were Zakat, war spoils, land taxes and gifts from the neighbouring governments, the details of which are beyond the scope of this article. It is, however, imperative to mention that compulsory monetary measures in Islam are not limited to Zakat or the spoils of war.

Based on society’s needs at the time, the Imam or Khalifa of time is free to establish a call for further donations. Examples of such can be seen during the period of Khulafa-e-Rashideen, such as the establishment of ushr (custom duty on imports) by Hazrat Umarra. Other non-Zakat based compulsory measures established during early Islam, such as fitrana, also formed sources of revenue of Bait-ul-Mal.

Initially, Bait-ul-Mal was a small room in the newly established Masjid al-Nabawi. This room was under the observation of Hazrat Bilalra. He was responsible for the state’s financial operations and those of the Holy Prophet’ssa household. A general impression among Muslims is that the Holy Prophetsa would not hold on to any income obtained and distribute it the same day; this understanding is only partially correct.

Medina was an established state with government expenditures. It catered to the needs of her citizens, in addition to funding and hosting delegations. Bait-ul-Mal funded the expenses arising from these operations. The Holy Prophetsa implemented the teachings of the Holy Quran with such excellence that the Quran itself bears witness:

“And we have not sent you [O Muhammad] except as a mercy to the worlds.”

To capture the ihsan of the Holy Prophetsa would be akin to capturing the oceans of the world in words – an impossible feat. Whether it was praying for the deceased folks of the Jewish faith, caring for the ill, helping carry items across town, forgiving the prisoners of war in exchange for teaching the children how to read, the Holy Prophetsa set exemplary standards in every aspect of life. This author finds it a daunting task to begin setting the tone of his benevolence regarding his welfare efforts, sufficient to quote the testimonial of the Holy Quran (Ch.33: V.22) that “you have in the Prophet of Allah an excellent model… ”

After the Holy Prophetsa passed, Hazrat Abu Bakrra faced many challenges upon his election as the Khalifa. Many prominent tribes, such as Banu Hanifa and Banu Tamim, refused to pay Zakat, rejecting it as one of Islam’s pillars. They promoted this mutinous belief, encouraged smaller tribes to join the rebellion and threatened to attack the Muslim state of Medina.

The young administration, still in infancy, decided to defend her rights as a state. Hazrat Abu Bakrra understood Zakat’s significance as a religious duty and an integral part of the state fiscal policy. Hence, he fought the rebels. His decision to defend the state preserved Zakat’s dignity and solidified the position of Medina as a unified state.

Owing to the soundness of this decision, when the Umayyads seized power after the demise of Hazrat Alira, the system of Zakat was well established, being administered by Bait-ul-Mal. These rebellious wars are collectively termed as the ridda wars (wars of apostasy). They include the wars against the aggressive tribes with no previous interaction with Islam (such as Sajah, Musaylima and Tulayha).

Musaylima, for example, considered himself an equal of the Holy Prophetsa and wanted to rule the Islamic State. After the demise of the Holy Prophetsa, he declared himself a prophet and started attacking the outlying Muslim tribes in the region of Bahrain (not to be confused with the current day State of Bahrain in the Arabian Gulf).

The purpose of various tribes initiating war against Medina was to use force and misinformation to render Muslim rule ineffective and achieve the broader objective of independence from the central Mediante rule. Throughout the tumultuous period, Bait-ul-Mal continued its servicing operation in Medina and throughout the areas of Muslim influence, without any discrimination of faith, gender or colour. Not only were Muslims covered by the welfare of the Islamic State, but the Christians of al-Hira and people of other faith enjoyed these benefits as well.

This is in contrast with the development of the Elizabethan era’s European welfare state, which focused on religion-based help (we explore this topic in part II of this article). When Hazrat Umarra was given the mantle of Khilafat in 634 AD, it was in a decidedly new era of prosperity for the Muslim dominion.

Recognising the demands of a geographical area with diverse cultures, languages and religions, he organised the system of revenue administration and formed the first known secretariat (diwan) in Islamic history. Bait-ul-Mal, together with diwan, was responsible for distributing stipends and benefits to all members of the society without any distinction of religion, race or colour.

It was under this secretariat that the first census was undertaken with the purpose of serving the entire population. The officers responsible for the revenue collection were directly appointed by the Khalifa and would report only to him. A register of beneficiaries was maintained (on a graduating basis) by the diwan. The census was critical in the identification of who to serve. The elderly, disabled and injured became the state’s responsibility and were allocated regular allowances to meet their basic needs. Abandoned children and orphans were taken care of by the state.

Hazrat Umarra would go through incredible measures to ensure that no one under his dominion went to sleep hungry, often touring the streets of Medina in disguise and distributing stipend with his own hands. The social welfare system grew to include pensions and grants to war widows and their children and old-age pensions. The benefits were extended to all citizens, including ahl al-dhimmah (the non-Muslim inhabitants of the State). The ahl al-dhimmah enjoyed the freedom to practice their religion as before.

The new Muslim rulers considered monotheistic religions such as Christianity, Judaism and Zoroastrianism as precursors of Islam. As they paid the jizya, they were exempt from serving in the military, which did not apply to Muslim citizens. The role of the government, under Khulafa-e-Rashideen, demonstrated the significance of the state taking a prominent part during times of national emergencies, such as famine and natural disasters.

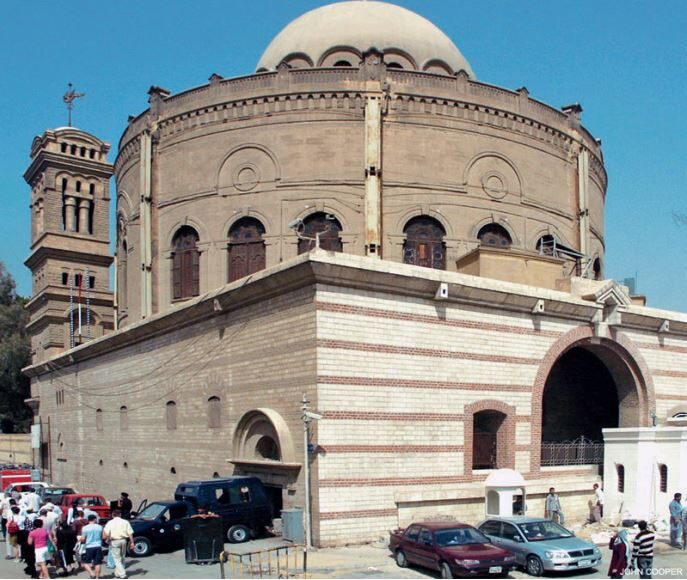

Even today, we observe nations like Canada and Germany, where governments took the decisive lead during the Covid-19 pandemic and were spared from the wrath of the disease. In times of drought and famine, the Islamic state took several special measures to counter the crisis. These included steps such as provisioning food from other provinces, halting some forms of corporal punishments and building of a canal between the River Nile and the Red Sea to speed up food delivery from Egypt. This canal remained operational for another 114 years, when in 755 AD, it was ordered shut by Abbasid Khalifa al-Mansur. This action cut the food supply to the holy cities, an unfortunate move that reversed the very motivation of Hazrat Umarra.

Picture credit: John Cooper at the University of Exeter’s Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies

The value of ihsan was not limited to the welfare of the downtrodden only. It extended to ensuring the well-being of travellers as well. Guesthouses were built along major routes to provide free meals and accommodation to the wayfarers.

In addition, debtors would receive help from Bait-ul-Mal, a concept that was opposite to 18th century Europe, where debtors were imprisoned, mostly for life. Islam strongly discourages the system of riba (interest) and promotes Zakat, which is the anti-thesis of interest. It would be prudent to discuss Zakat in brevity. Zakat holds a unique position when compared to the other four pillars of Islam. Its uniqueness extends from the fact that it is a form of worship as well as a financial obligation to the society.

The parting from the wealth for the sake of Allah’s love draws a person nearer to Him, while seeking His pleasure by providing for His creation helps maintain a balance in the society and removes social ills, helping to reduce crimes. While Zakat is often referred to as charity, it is far from it. The Holy Quran declares Zakat as the rightful property of eight distinct beneficiary groups (Surah al-Taubah, Ch.9: V.60).

This distinction highlights the difference between charity and benevolence. It could be said that Zakat is the first institution of social welfare in Islam. The first two categories of the eight beneficiary groups are the poor and the needy. There are no minimum criteria that define this group, only their inability to satisfy the basic needs of life. This permits the Bait-ul-Mal of each society to determine the dominant standards of the time. The remaining beneficiaries fall among various categories such as freeing people of slavery (or prisons), travelers in distress etc.

One aspect of Zakat is to help people who have been suffering from financial debt. In Arabia, the system of interest in place was unfair towards the borrower, allowing the lender to earn the loaned amount many times over. Islam forbade such a practice as it encouraged the hoarding of wealth. From an economic point of view, the circulation of wealth is critical for the economy to function. The system of riba encourages holding on to wealth to gain more interest.

From this point of view, the debtors were assisted by the state, helping them come out of debt and become economically stable. Even during his youth, the Holy Prophetsa would leave no stone unturned to free a slave. His successors elegantly pursued this practice and one of the tasks of Bait-ul-Mal became manumission of slaves. That education plays a critical role in Islam is a gross understatement.

During the early years of Islam in Mecca, even during intense persecution, the Holy Prophetsa established Dar al-Arqam, a school where the first Muslims were trained. When the Holy Prophetsa migrated to Medina, there were an estimated 11 people who could read or write, apart from the Jews. How, within a few years, Medina became dar-ul-qurrah (abode of literates), speaks volumes about the efforts of the Holy Prophetsa to educate the Muslims. This mantle was elegantly carried by all his successors, who understood its importance and took steps to ensure the education of the masses. They understood the role of education in coexistence with other cultures and faith.

To ensure that quality education was available to all Islamic state citizens, salaries of teachers and stipends for students became an integral function of Bait-ul-Mal. Education became a responsibility of the state. The schools broadened their students’ minds with gems of the Holy Quran, science, law and mathematics. The effects of this education system were so far-reaching that hundreds of years later, the University of al-Qarawiyyin was formed in Fez (Morocco) in 859 AD. This was the first degree-granting educational institute in the world and is still in operation.

After Hazrat Umarra, the system of social welfare continued to be maintained with the same zeal by his successors Hazrat Usmanra and Hazrat Alira, the third and fourth Khulafa-e-Rashideen (rightly guided Khalifas). However, when the period of Rashidun Khilafat ended, so did the social welfare in the Islamic state.

Hazrat Umar-bin-Abdul Aziz (717-720 AD), a pious caliph, revived it during his brief reign. Unfortunately, during the later period, the system gradually disappeared due to a lack of personal interest from Muslim rulers.

Philosophy of welfare in Islam

In an age where government welfare is frowned upon by some, the Islamic system of Zakat as the driver of social welfare may be seen as an undermining work ethic. However, a cursory study of Islamic philosophy on being dependent, while fully able to work is sufficient to understand the fallacy of such a belief.

In most simple terms, the philosophy of the Islamic welfare system is to bring the surplus wealth into circulation and to ensure the balance and just distribution of the wealth among the poor and the needy. It does not stop there. The central idea is to help those in need when they need it the most and once they are able to stand on their own, they should extend a hand to those in need.

A quick view of the two primary sources of Islam, namely the Holy Quran and the hadith, sufficiently advocates desire, value and dignity of work. Islam condemns living off others while being able to work. If there are employment opportunities, regardless of the perceived social status, a person cannot choose to remain unemployed.

Islam emphasises the importance of work and encourages people to earn their living, stating, “No one ate better food than the person who laboured with his own hand.” The Holy Prophetsa would often pray, seeking Allah’s refuge from laziness and idleness.

A hadith tells us how the Holy Prophetsa transformed a member of the Ansar from a beggar into a productive member of society by teaching him how to work and provide for himself. Centuries later, ihsan, as a state policy, was developed into a welfare state by Western nations. As oil became a significant income source, some Muslim states established their own version of a welfare state.

In part II, we shall discuss the modern implementation of social welfare and social contracts in Western society and the inspiration driven by Islamic principles.

References used (in order of consultation):

- Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmadrh (translator). The Holy Quran

- Imam Abu Dawud. Sunan Abu Dawud. trans Prof Ahmad Hasan. Kitab Bhavan (2013)

- Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas. Philosophy of the Teachings of Islam. Islam International (1996)

- Hazrat Mirza Nasir Ahmadrh. Khutabat-e-Nasir. Vol 2, Sermon #74, 76 & 82. Nazarat Ishaat Rabwah (2005)

- Ibn Kathir. The Life of the Prophet Muhammad. English translation by Prof Trevor Le Gassick. Center for Muslim Contribution to Civilization (1998)

- Seyed Sadr. The Economic System of the Early Islamic Period. Palgrave (2016)

- Shibli Nomani. Al-Farooq (translation). Muhammad Ashraf publisher

- Michael Bonner. Poverty and Charity in the Rise of Islam. Suny Press. 2003. 13-30

- Dr Hameedullah. Khutbat-e-Bahawalpur, Idara Tahqeqat-e-Islami Islamabad (1992)

- Abdul Rashid Moten. Social justice, Islamic State and Muslim countries. Cultura 10, no. 1 (2013): 7-24.

- Al-Otaibi & Rashid. The Role of Schools in Islamic Society. The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences. 14:4 (1997)

- Amelia Fauzia. Faith and the State. Brill (2013).

- Abdul Azim Islahi. Islamic distributive scheme. Aligarh (1992).

Jazakumullahu khairan!

Jazakumullah u khairan