Asif M Basit, London

For the last three decades or so, Jalsa Salana Germany has taken place just a month after the UK Jalsa Salana. There have been exceptions but this has always been the pattern. This year’s Jalsa Germany was even less than a month apart from Jalsa UK – falling just a few days short.

As Jalsa UK came to its end, the MTA team in Germany Studios went head-on into preparations for the three-day live transmission of Jalsa Germany. In doing so they took us, here at MTA International in London, with them. Without a break, we were wrapped up in programmes and other content to be broadcast during Jalsa Germany’s live transmission.

Unlike most of us, Huzoor’saa Jalsa UK does not end with the concluding session on the third day. He stays extremely busy meeting delegates and dignitaries who travel from all parts of the world to meet him and seek his guidance on various matters. The same remained the case this year and it seemed that Huzoor’saa Jalsa UK engagements might end only with his departure for Jalsa Germany.

While MTA Germany studios were occupied with preparations of what we call a rundown or a running order in television lingo, there came a news that kind of watered down the heightened enthusiasm – albeit for a few moments.

There came the news from Huzoor’saa office that upon medical advice, Huzooraa will no longer be undertaking the tour for Jalsa Germany. It wasn’t a very smooth pill to swallow for even us here in the UK, not to speak of the German Jamaat who had been eagerly looking forward to welcoming Huzooraa to their land.

The news came along with the instruction from Huzooraa that he would deliver all his addresses to the Jalsa via video link and that the three-day live broadcast would happen live, as usual, from the MTA studios on site.

The first thing I could think of was to pick up the phone and call the German studios as, in the wake of the changed situation, the entire running order would require a complete redressing. The running order, for the entirety of its duration, was woven around Huzoor’saa engagements and activities during the Jalsa – what nazm to play when he arrives, what to say in the studios when the bai’at is about to start, what discussion to happen in the studio when he delivers such and such address etc. It was as if the lynchpin had been pulled out of our plans.

When I called Arsalan Sahib, the person in charge of MTA Germany studios, he was ready with the team of presenters for this urgent meeting. I felt in their voices a note of sadness but in no way did this sadness carry even a hint of disappointment. The reasons for Huzooraa not travelling were spelled out by Huzooraa, and who would want him to ever put himself at any risk? For an Ahmadi, nothing takes precedence over Huzoor’saa well-being – as they say, Ahmadis can die for it.

The team recovered from their melancholy in just a moment’s time and was up for taking up the challenge and making the Jalsa broadcast a success. Huzooraa, in the message to the German Jamaat, had said that he might not be physically present among them, but he would see them and their Jalsa through the lens of the camera. This left MTA with an even greater responsibility as among their viewers now was the one viewer who they could not afford to disappoint.

As our discussion meandered on, I could feel in every member’s voice and tone, the zeal and enthusiasm of a soldier at the frontline, ready to take on the chin whatever challenge comes their way.

Since the wake of this change had not altered the duties of our department, I sought Huzoor’saa guidance and had my permission to travel to Germany renewed.

I arrived there on the Wednesday before Jalsa and was driven straight from Frankfurt airport to the place where I was to stay for the days of Jalsa Salana Germany. As we drove into the accommodation facility, my eyes met a sight that took my attention in a very strong grip. A few yards away stood a huge cathedral-like building with its towers and spires standing tall and high, giving the building a majestic height. It captured my attention so much that as soon as I settled in my room, I looked up the internet to find out more about the building.

It turned out the building was Laach Abbey, a monastery founded around 1093 CE. From the time it was built to the time that I had seen it – a few moments ago – lay an unimaginable stretch of a whole millennium. Benedict monks had worshipped in this building for a thousand years – praying to God for the return of Jesus Christ.

A millennium of prayers, and here they were today, with the Messiah’s community just a few hundred yards away from them. If they climbed to the top of the towers, they could have easily seen the white-tent-city that lay in the valley of Mendig, ready to profess and preach the message of Islam – the message rejuvenated by the Messiah of this age.

Caught in the awe of these thoughts, I fell asleep. The next morning, I got up quite early only to realise that the feeling of the monastery and the Jalsa site being so close apart had still not loosened its clutches on my imagination. As I tried to make the best use of the early morning through prayer, the monks just a few yards away from me kept coming to my mind who had worshipped right here for a thousand years. The thought of them praying for the return of Jesus Christ for all this time, and the presence of the community of the Promised Messiah assembling so very close to them fascinated me a great deal. The Messiah was at their doorstep.

I spent five days in Germany, and each one of those five mornings had a tint of this inspirational feeling. The monks, their worship, their desires for their Lord Jesus to return, and the millions of tears that must have been shed during prayers in this monastery were all elements of a romance that just wouldn’t let go of my mind.

But then the day would start and my responsibilities would carry me away from all this to the Jalsa Gah, where I would head straight to the MTA office and get on with the day’s work.

During the day, I would witness hundreds of faces in the Jalsa Gah shining with the light of faith. This shine had dimmed a few days ago when they had learnt that Hazrat Khalifatul Masih, their beloved Imam and master, was not going to be among them for the Jalsa. But then they realised that the technological advancement was there to serve the Promised Messiah and his Khalifa and, of course, his Jamaat too.

With this, the lost radiance returned to their faces and this group of faithful Ahmadi Muslims were happy, praying for the wellbeing and good health of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih.

Thus passed the three days of Jalsa and I was set to return to the UK the following morning. My work at MTA was over and I returned to my room. The sun still shone brightly in the afternoon of a German later-summer day. I was alone in the room and had no company, save the emptiness that attacks the heart when Jalsa comes to its end.

I got a call from Mateen Sahib, who was volunteering with the hospitality department, telling me that he would pick me up at half past nine the following morning to drop me at the airport.

Tired from the three-day marathon of work and with nothing much to do, I decided to call it a day. I lay in bed trying to learn about the beautiful valley where the Jalsa Salana Germany had happened. The more I read, the farther I drifted from calling it a day – I read quite late into the night.

The new site of Germany’s Jalsa is on the outskirts of a town called Mendig, which lies in the scenic Eifel mountain range in the Rhineland-Palatinate area of Germany.

A couple of years before World War II, an airbase was built in Mendig for military training. It came in handy during the war to keep a check on the Allied forces trying to make their way through France into Germany.

In the spring of 1945, the American jets had taken control of the Mendig airbase as the Allied forces penetrated into Germany, before bringing her to her knees and finally taking control.

In the post-WWII years, as Germany recovered from its war-torn state, the airbase remained in use for military training. With a shrinking army, the airbase became defunct and is used today as an airfield for flying aficionados.

Call it a coincidence if you like, I find it a bit more than just that. A site built in the name of war, for the war, used during the war and its atrocities, is now home to a convention that now resonates, not the roars of fighter jets, but the voice of Khalifatul Masih as he invites the world towards the last chance of peacebuilding through Islam.

This Eifel mountain range came into being through a volcanic eruption around ten-thousand years ago. The volcanic eruption was at such a grand scale that it had led to major climate change in the area for many decades.

The lava had spilled to a radius of around forty kilometres, creating bumps and craters, turning the area into what is now known as Europe’s youngest landscape created through volcanic activity – the youngest and ten-thousand years old.

Majority of experts in volcanic activity are of the opinion that the volcano is no longer active, but there is a school that believes that the lava is asleep and might well wake up one day, to create an activity of a similar scale to the previous one from ten-thousand years ago.

I am not a geologist or an expert in volcanic activity, but I do believe that spiritual tectonic plates in the region are on the move – deep below the surface of the land from where Mrs Rose had identified the Promised Messiahas and admired his message. She once sent him a rose in the envelope with a letter asking for it to be kept safe as evidence of Germany’s inclination towards his message.

Volcanic activity might be dormant under this land, but the lava of faith with all its heat and force is ready to erupt and eradicate the ice-cold state of faithlessness from this region.

So while my five-day stay in Germany was eventful as it was with Jalsa Salana and my duties, but these thoughts and feelings made it even more memorable.

And before I close this piece, I must take you with me on my half-past-nine lift to the airport.

I woke the next morning, went through my morning routine and was ready at nine o’clock – half an hour before my pick-up time – when Mateen Sahib called to say that he would be coming at half past ten which is a more appropriate time to leave for the airport.

As if I had wanted this to happen, I shot up from the chair and headed straight out, took one right turn, one left, and about a hundred steps, and there I was: right in front of the monastery. I looked at it from a distance to take it all in – with all its grandeur, majesty and towering height.

I walked towards what I could sense from the distance I was at that the building, like most Benedictine monasteries, had a cloister wrapped around it. I stepped into the cloister and found myself in an air laden with rich history. The mighty doors that led into the monasteries stood proudly at either end of the cloister. I went to the one on the right-hand side and pushed it open. It required more strength than I had given it – and why not as behind it was the weight of centuries of meditation and prayer, hope and desire, longing and yearning.

In less than a second, I was inside the monastery, all by myself. I could hear my steps echo as I walked through the space of the monastery that was heavily filled with aura. I walked to each artefact hanging on the ancient walls.

All of a sudden, I gasped as I saw a shadow on the altar, all dressed in black. The gentleman approached me and with a very kind smile, held his hand out which I shook with haste – haste because I was waiting to bump into someone I could talk to about the monastery.

I told him how I had remained in the awe of the monastery’s building for the last five days and the awe had brought me wandering into it.

Understanding my destitute desire to know about the monastery, he introduced himself with his name and that he lived in the monastery as a monk. I must have seemed childishly pleased with everything he was telling me that he took me around the monastery.

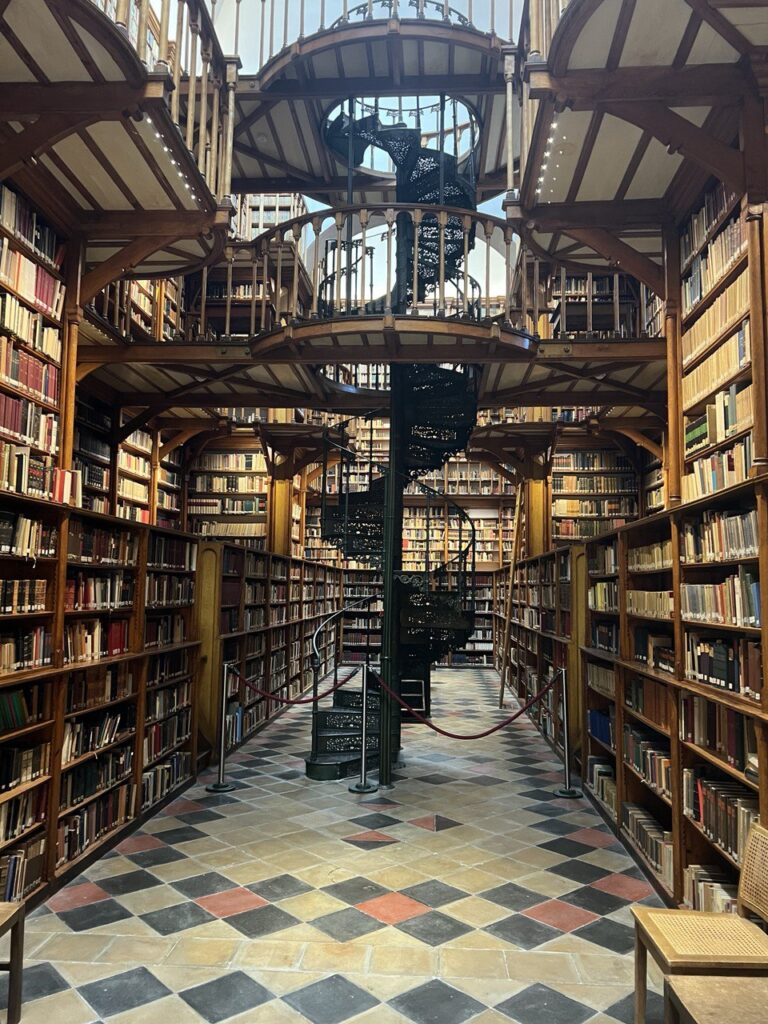

As he opened the door to the library, I was, in the true sense of the proverb, like a child in a candy shop.

I told him that I had imagined the monks of this monastery worshipping every morning.

“Around what time?”, he asked.

“About five o’clock!”, I replied as I wondered why he had asked this.

“Oh! That is exactly the time when we say our first prayer!”

Sensing what he might be wanting to ask further, I told him why the monks had dwelled on my imagination so early in the morning.

“I have a special connection with you. You wait for a Messiah to return, I believe that he has returned. This Messiah is what bonds us together”, I finally revealed to my newfound friend.

He extended his hand once again and I shook it. We spoke about other things that made me feel comfortable in the place I was in. We could have spoken more, but it was almost half-past-ten. He was a monk and wasn’t going anywhere. I wasn’t a monk and had to catch my flight.