Asif M Basit, London

Browsing through some photographs in the Jamaat’s records, I came across an album with photos of an office in Aiwan-e-Mahmood, Rabwah. The office seemed newly renovated and the furniture and its decorum too were immaculate. Intrigued, I enquired as to who was behind it and was told that Mubarak Ahmad Tahir Sahib had made donations for the renovation and the paraphernalia.

Whenever this name was mentioned, the question that would usually follow in Jamaat’s official circles was, “Which Mubarak Tahir?” The witty answer that usually followed would either be “the legal one” or “the illegal one”.

The story behind this is that there were two persons in the Rabwah offices with the name Mubarak Ahmad Tahir. One was the legal advisor of the Jamaat, while his namesake, as jolly as he is, had allowed to be referred to as the “illegal” one.

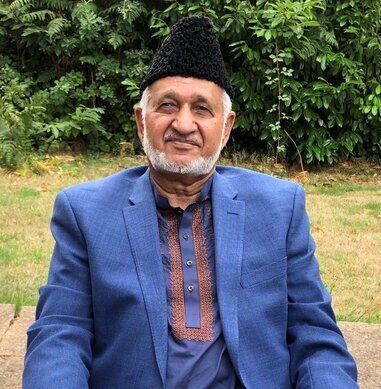

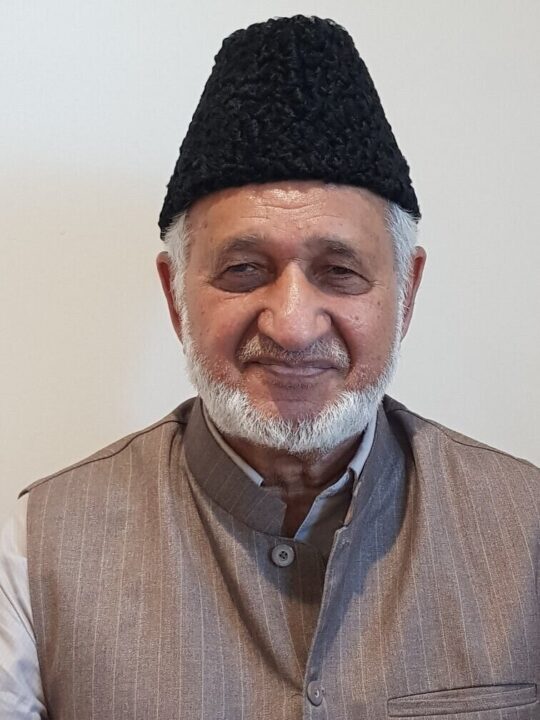

With the demise of the “legal one” on 17 February 2021, this confusion has, with him, been laid to rest. Sad as it is, Mubarak Ahmad Tahir Sahib will now be mentioned in the past tense, bringing to its end the joke that always entailed the mention of his name.

Now coming back to the album that led to my intrigue and the discussion it had ensued, it was the first time I had heard him mentioned ever since I had left Pakistan and settled in London. I had often seen him travelling to and from his office in his Suzuki Margalla (a saloon car, popular in Pakistan) with a great level of dignity. This was the most I knew of him in my Rabwah days.

I would occasionally see him with some colleague walking in the corridors of the Jamaat’s offices and both would be amused and laughing. What always perplexed me was that someone very gracefully dressed, always wearing a Jinnah cap and in charge of legal matters, could carry, alongside all this, such a jolly disposition. So all I got to know about him in my Rabwah days was he had a cheerful but dignified personality.

I lived in a mohalla (neighbourhood) called Dar-ur-Rehmat Wasti, but would spend most part of my day in Dar-us-Sadr Gharbi – the Tahrik-e-Jadid staff colony. This was because the very first friends I had made in college would play table-tennis in Ansarullah offices every afternoon, leaving me with little choice but to be with them.

As part of my tarbiyat, my father insisted on my not staying out after maghrib, so straight after those games, I would head to Masjid Mubarak or Masjid Mahmood (Tahrik-e-Jadid colony) before making my way back home. Mubarak Ahmad Tahir Sahib was a regular worshipper at both these mosques. This worked as his second introduction.

For the youth that had unfortunately deprived themselves of education, there were very limited opportunities of employment in Rabwah. One of such young men, who was born in the Tahrik-e-Jadid colony, grew up there, stepped into his adulthood and fell so much in love with every nook and corner of the colony that was left incapable of doing anything else but to roam the streets all day. His mercurial nature and the subsequent indolent life had gained proverbial status that parents would allude to when persuading their children to take studies seriously.

No one in Rabwah was ready to take him on for any kind of employment, when one day, news spread that he had got a job. So unbelievable it was that it was the hottest topic in the playground of Tahrik-e-Jadid that day. It turned out that the one who no one dared bet on had been taken on by Mubarak Tahir Sahib as an office-boy. This was the third introduction of Mubarak Sahib for me.

The fourth introduction came with the photo album I have mentioned above. With this came the knowledge that his philanthropy did not start and end with the office I had seen in the photos, but extended to several projects of the Jamaat. He donated wholeheartedly wherever he possibly could.

When his son, Hafiz Ijaz Ahmad Tahir Sahib, was appointed in England and when a bond of friendship developed between us, is when I got to know Mubarak Tahir Sahib much more. Mubarak Sahib would stay at his son’s home for Jalsa Salana UK and his stay would provide a chance for an encounter or two.

Jalsa duties require such complete attention and absolute devotion that one has to seek leave from even his own family for the entire period of Jalsa and at least for a week before and after. So these encounters with Mubarak Tahir Sahib remained very brief and my acquaintance with him never delved deeper than the brim – more of a view than experience.

Writing these lines, I regret that I couldn’t have known him more, yet happy to even just known a noble person like him. The handful of memories I have of him are precious and I am hesitant in letting loose my grip, lest they slip through my fingers like sand. Yet his memories are worth sharing as we can all learn from them.

The first time I was set to meet him in Islamabad, UK, I was a bit nervous. This was down to the awe of his personality but also to the little introduction we both had of one another. But as he walked in, he broke the ice and broke it well: “Oh, masha-Allah! How are you? Where have you been? We never got to meet for so many days!”

These warm words that came with open arms made me feel like we had known each other all our lives; so much so that I even felt ashamed for not having come to meet him earlier. It was only later when I realised that this warmth and welcoming gesture was part of his pleasant character. He met everyone, even strangers, with the same welcoming remarks and gestures, leaving everyone who met him feel that he knew them very well; even leaving some ashamed why they had stayed away in reluctance.

However, this warmth was a very natural outcome of his loving personality that worked as a repellent for the fog of alienation and as a magnet to draw people closer to him. Had it not been for this, how would the younger generation muster up the courage to open up to someone so senior?

He would sometimes visit England out of the Jalsa season. Encounters during such visits were more often and slightly more detailed. The first of such meetings that I remember was one where a friend of mine who happens to be a lawyer accompanied me. With every room filled with family guests, Hafiz Ijaz Sahib had put up a gazebo in his front garden. It was there that we sat with Mubarak Tahir Sahib. He ordered children for food to be laid out for us to have dinner with him.

With dinner commenced a long series of questions posed by my lawyer friend to Mubarak Sahib. A question needs only a few seconds to be uttered, but its answer takes its time. We continued to eat and Mubarak Sahib, indifferent to his meal that lay before him and indulged in his talk, continuously answered all questions, hence enlightening the young man who shared the same career with him.

I remember Mubarak Tahir Sahib furnishing this young lawyer with the history of the Jamaat’s legal affairs. It was like witnessing a transfer of knowledge from one generation to the next. Relevant as it was, Mubarak Sahib mentioned the names of many lawyers who were instrumental in the Jamaat’s legal affairs. Some of them were his seniors, some contemporaries and others were much younger. But what struck me the most was that he mentioned each one of them with utmost respect and the mention of each was far from even a hint of professional jealousy. I also had the chance to witness him meeting these lawyers and the respect he showed them was aligned with the one he had shown in absentia.

On another occasion, I had the chance to travel with him from London to Islamabad, Tilford. To make the best of this opportunity, upon my request, he shared with me a great deal of information to do with his services for the Jamaat. At the end of the journey, I had got to know him more.

Of what I gathered in this conversation, the most significant observation must be mentioned here. He had devoted his life in the time of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIIrhand had had the chance to be trained as a waqif-e-zindagi directly through the same great mentor. But he had not let himself get swamped in that era. His love for Hazrat Mirza Nasir Ahmadrh, as a person aside, his love for Khilafat-e-Ahmadiyya was the actual foundation of his personal philosophy and practice. He moved on making smooth transitions with the changing times and eras.

His love for Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IVrh too was vividly conspicuous. And talking of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Vaa, it was not hard for anyone to observe that he was living in this age with heart and soul and with absolute devotion.

Another aspect of Mubarak Sahib’s personality that one would notice without any effort was his love for the members of the family, and even the greater family, of the Promised Messiah. Even with members who were younger than him, he would show affection with an unmissable tint of esteem.

Of the members of the Promised Messiah’s family, the person he mentioned most and with most admiration and reverence was Sahibzada Mirza Mansoor Ahmad Sahib. He would fondly relate how Mirza Mansoor Ahmad Sahib had played a great role in his rearing as a waqif-e-zindagi in general and as the Jamaat’s legal advisor in particular. He would never miss mentioning the insight, foresight and valour that he had witnessed in this great stalwart of the Jamaat.

Whenever I met him, and whatever he talked about, the pivot of the discussion remained loyalty to and obedience of Khilafat. He took this to be the soul of an Ahmadi’s existence.

He would mention how he came from a family with an agricultural background, where even making it to college was a huge deal. However, he somehow carried on to obtain a degree in law and later, in the time of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIIrh, devoted his life for the cause of Islam Ahmadiyyat.

He was first posted to Uganda, but later got called back to work in the markaz at Rabwah. He would mention the time when he served in Khuddam-ul-Ahmadiyya, especially during the tumultuous times surrounding 1974. The situation for Ahmadis had become very uncertain and it was paramount that the morale of Ahmadi youth was kept high, lest they fell prey to despair and dismay. Mubarak Tahir Sahib accompanied Mirza Ghulam Ahmad Sahib and Mirza Khurshid Ahmad Sahib in getting playgrounds into better shape in every mohalla of Rabwah where sport could be reignited as a means of injecting and upholding the positivity in the youth’s outlook. It was thenceforth that the playground culture returned with all grounds in Rabwah thriving from Asr to Maghrib every day.

When he told me that Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIIrh had given the Jamaat the motto “Always keep smiling” in similar days of hardship and trial, I would see how Mubarak Sahib had never failed to practically follow those words.

On occasions, one would easily notice that he was visiting Huzooraa regarding some serious and complex issue of the Jamaat, but what would equally remain noticeable was that he never forgot to wear his smile. I must take this opportunity to mention that although he would use the case-study method – typical as it is in the profession of law – he would never give away names or any unnecessary information. The case-study would only serve as a means for him to impart knowledge to the younger generation.

This quality is something we all need to instil in ourselves, more so in a time when everyone carries a phone and every phone, a camera. This level of secrecy can only be maintained when each one of us develops a sense of belonging with our work and never takes it as something forced upon us; to safeguard our official matters as one safeguards one’s own secrets and the secrets of one’s home and family.

As Mubarak Tahir Sahib and I drove back from a journey in Hafiz Ijaz Sahib’s car, we stopped at a riverside restaurant, near Islamabad, for a fish-and-chips lunch. Mubarak Tahir Sahib’s insightful conversation – and the buzz and bloom that naturally came with it – turned that beautiful, sunny, summer afternoon even more vibrant. It was as if three friends were enjoying lunch together. There was no undue hesitance. Although Mubarak Sahib never demarcated walls around himself, yet the awe of his persona would help maintain the distance required to uphold his dignity.

I say three “friends” only to describe the level of liberty we all enjoyed that afternoon. Otherwise, it is worth mentioning that not a single moment of that time or single sentence of that conversation was pointless or without purpose.

A major part of that day’s conversation revolved around his memories of working with the Khulafa-e-Ahmadiyyat. How his face glowed with love for them is before my eyes as I write these lines.

He mentioned how he had had the blessed opportunity as mohtamim umumi to play a role in the security team of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IIIrh. He would ride his bicycle parallel to Huzoor’srh car as he travelled to Masjid Aqsa for the Friday prayers. Once, Huzoor’srh car had to come to a halt in heavy traffic or on a level crossing and Huzoorrh had rolled down the window and congratulated him on his new-born and had given a name to the baby.

He also told how he was appointed the legal advisor of Sadr Anjuman Ahmadiyya and Tahrik-e-Jadid both by Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IVrh. How he remained the recipient of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IV’srh grace and blessings was one of the long chapters in his life.

As the afternoon drifted towards evening, Mubarak Sahib told us about the trying times when Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmadaa (then nazir-e-ala and amir-e-muqami of Pakistan) was made victim of anti-Ahmadiyya laws in Pakistan and had been tried in court for a false accusation. This had led to Hazrat Sahibzada Sahib’s arrest, resulting in the privilege to be imprisoned in the way of Allah. The pain that the whole Jamaat had to go through flooded his eyes as he recalled those days of agony.

His memories from those days have been broadcast on MTA as part of a documentary and I feel fortunate to have listened to them first-hand. I was, thus, able to witness the waves of emotion that one would otherwise conceal in the presence of a rolling camera.

As it carries a lesson for us all, I deem it essential to highlight one incident that he narrated. As soon as the Jamaat’s administrative body in Pakistan realised that a lawsuit had been set in motion against Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmadaa, it became certain that his arrest would definitely follow.

A committee of some senior members, with Mubarak Tahir Sahib on board, wrote to Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IVrh suggesting that Sahibzada Mirza Masroor Ahmad Sahibaa be asked to flee the country. But as soon as Sahibzada Mirza Masroor Ahmad Sahibaa found out, he expressed his disapproval for such a suggestion and that too without his consent. He immediately got in contact with Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IVrh in London and clarified that he had no fear of anything that came his way and that he had nothing to do with the proposal of escape.

Mubarak Sahib was part of the committee that had shared the mistake, but he never held back the details and narrated the whole incident. He saw, in this story, a moral that could benefit others: to openly accept one’s mistake and to let it be known to others so they can learn a lesson out of it.

It was this openness with the younger generation that enabled him to build bridges over the generation gap. And it was through this quality of his that I saw his youngest grandchildren hugging him without hesitation; the older grandchildren could be seen walking and talking and joking with him as he strolled up and down the greens of Islamabad with them.

This gesture of kindness towards his grandchildren was as if to say, “Be friends with your younger generation so they don’t hold back, or else they might head into the burrows of the Internet to seek answers; where they might end up, no one knows!”

May Allah enable us to have a friendly and loving relationship with our younger generation.

Mubarak Sahib lived a very simple life as a waqif-e-zindagi, despite the fact that Allah had granted him affluence. With this affluence, he was fortunate to have been blessed with generosity and open-handedness. The cherry on the cake was how he put all these qualities into practice by gelling them together with faith and piety.

A great deal of his wealth went for the cause of the Islam Ahmadiyyat, but even when giving to his children, he would hand it out in a wrapping of virtue. For instance, when Hafiz Ijaz Sahib’s wife devoted herself to driving Mr and Mrs Mubarak Tahir Sahib to and from the Jalsa Gah, the mosque and wherever they desired to visit, he showed his gratitude by saying to Hafiz Sahib, “Our daughter-in-law’s car does not seem to be as reliable as it should be. Look up on the Internet for a decent car and let me know how much it costs.”

With the passing years, I also went through the painful experience of witnessing his falling health. When I first got to see him at Jalsas, he would walk upright and with great speed. With passing years, his steps and speed both began to seem slightly weathered. Then appeared a walking stick in his hand and then medical-grade shoes on his feet. Another year or two and his steps no longer remained as crisp as I had once seen.

What I must mention here is that none of the above waivered his confidence and never did it seem that he had given in. He would walk with an upright posture and would ignore every stumble as if he hadn’t felt it.

Autumn had set in on his body but had failed to break in and touch his soul. He had no room for it in his outlook of life and it is this that kept him going and serving the Jamaat till his very last breath. In all these stages of declining health, the one thing that always remained the hallmark of his personality was his walk to and from the mosque.

Everything said and done, time is ruthless. It hurt me to see someone I had seen standing upright in the rows of Masjid Mubarak, Rabwah seated on the back benches of Masjid Mubarak in Islamabad, Tilford. But at the same time, it was faith-inspiring to see that whether Mubarak Sahib walked up the ladder of life or down its descending staircase, his destination always remained the mosque; a threshold that he never let go.

The last time I remember seeing him was during his stay in Islamabad, Tilford, in 2019. It was in the month of Ramadan and Hazrat Khalifatul Masih V’s dars was about to commence. Mubarak Sahib walked through the crowd with one of his grandsons. I saw him go into the mosque and being ushered towards the chairs that were placed outside the mosque. As he settled down there, another person on duty approached him and asked him to go to the seating area in the adjacent hall. He was making his way when he was told to go back into the mosque. With this series of instructions, Mubarak Sahib very obediently complied as they came. There was no sign of anguish or displeasure on his face or even his body language. This is my final memory of Mubarak Ahmad Tahir Sahib.

I feel a dual connection with Mubarak Tahir Sahib; one for what I learnt from him and the second, for my friendship with his son, Hafiz Ijaz Ahmad Tahir Sahib. This dual connection doubles the grief I have felt on his demise. However, if grief and sorrow have not blatantly been felt in this write-up, I would like to clarify my position to my readers and Mubarak Sahib’s family.

For someone who led a long and successful life, and whose every moment was momentous in the service of the Jamaat, and who always loved to smile and laugh, I find no urge in myself to bid him farewell with an air of melancholy. Why not say this final good-bye with a smile on our face and leave him in the caring hands of God? By doing so, we will forever remember him with his signature smile.

I have been told that when his friends were called for a final viewing before his burial, one of them refused and said, “I want to remember a smiling, laughing Mubarak Sahib; not one wrapped up in a coffin”.

The lines above are my humble words and not worthy of being called a tribute to Mubarak Tahir Sahib. So I conclude it with the mighty and faith-inspiring words of my master, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih V, may Allah always be his Helper.

I had the honour of an audience with Huzooraa on the morning of 20 February 2021. The demise of Mubarak Sahib had happened a couple of days earlier and that too of Khalid Mahmood-ul-Hassan Bhatti Sahib. After expressing my condolences, I said to Huzooraa:

“One feels shattered with the news of a dear one passing away, but Huzoor has had to receive a number of such sad news, one after the other. Where does the courage to bear such grief come from?”

Huzooraa replied:

“Nothing works before the will of God Almighty. Sooner or later, everyone has to pass. No one is going to live forever. So the only truth is that:

بلانے والا ہے سب سے پیارا، اسی پہ اے دل تو جاں فدا کر

“[The most beloved is the One Who recalls; so, O my heart, let us lay our lives before Him.]

“This not only inculcates forbearance in one’s heart but also makes one progress in trust in Allah. Don’t you remember, when I mentioned Chaudhry Hameedullah Sahib in my sermon, I concluded by saying, ‘May Allah grant more helpers for Khilafat-e-Ahmadiyya’.”

After a brief pause, Huzooraa said:

زندگی انساں کی ہے مانندِ مرغِ خوشنوا

شاخ پر بیٹھا، کوئی دم چہچہایا، اڑ گیا

“[Life is but like a singing bird; that settles on a branch, sings for a while, then flies away.]

“So, such is life! And have you also heard where they say:

زندگی کی دوسری کروٹ ہے موت

زندگی کروٹ بدل کر رہ گئی

“[Death is another side of life; ’Tis as if life just turns its side.]”

So let us bid farewell to Mubarak Sahib with the prayer, in Huzoor’s own words, that may Allah continue to provide such faithful aides to Khilafat-e-Ahmadiyya. Amin.