Iftekhar Ahmed, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre

Central to Islamic teachings concerning modesty and interaction between genders is the following question: What is the ruling (hukm) on a man intentionally directing his look (nazar) towards the face of a woman unrelated to him by marriage or close kinship (ghayr mahram)?

This subject requires careful consideration owing to the widely held view among classical jurists within Islamic legal scholarship that a woman’s face, unlike other parts of her body, does not constitute ‘awra requiring mandatory covering (satr) in every situation. This exemption is generally understood to arise from interpretations of scriptural exceptions, such as “except that which is apparent thereof” (illa ma zahara minha) in Surah an-Nur, Ch.24: V.32, and considerations of necessity (darura or haja) connected with daily life, testimony and ritual obligations like prayer (salah) and pilgrimage (hajj).

The main point of divergence, consequently, becomes evident when determining the necessary legal implications (lawazim shar‘iyya) of this non-‘awra status for the separate hukm governing the man’s act of looking. Does the concession (rukhsa) regarding her covering automatically permit him to look, conditional upon certain subjective factors – the absence of desire (shahwa) or perceived risk of temptation (khawf al-fitna) – being apparently met? This viewpoint, representing a notable interpretive direction seen in early Hanafi reasoning, the prominent Maliki view, which suggests agreement on the permissibility of looking without desire, and the Zahiri school, essentially puts forward a principle of direct correspondence: the permissibility of uncovering for her implies permissibility of looking for him under these conditions.

Conversely, the position argued for in this text is in favour of separating these two rulings. This view finds strong support in the relied-upon (mu‘tamad) position within the Shafi‘i school, championed by scholars such as al-Juwayni (d. 478/1085), an-Nawawi (d. 676/1277) and later commentators like Ibn Hajar al-Haytami (d. 974/1566) and ar-Ramli (d. 1004/1596), the main Hanbali perspective, arising from the school’s emphasis on precaution, the cautious approach adopted by many later Hanafis concerned with the corruption of the times (fasad az-zaman) and, most importantly, the preventative philosophy expressed by the Promised Messiahas.

This position holds that the ruling governing the man’s gaze operates under distinct textual commands and legal principles. Principal among these are the proactive divine injunction for lowering the gaze (ghadd al-basar) in Surah an-Nur, Ch.24: V.31, interpreted as a primary preventative measure, and the broad jurisprudential principle of blocking the means to potential harm or sin (sadd adh-dhara’i‘). From this perspective, the rukhsa related to the woman’s satr, granted owing to hardship (mashaqqa) or necessity (haja or darura), does not nullify the independent primary ruling (‘azima) guiding the man’s conduct. This primary ruling gives precedence to preventing fitna at its source by addressing the inherent susceptibility of human nature to temptation, making reliance on subjective self-evaluations of intent insufficient as a primary legal safeguard.

This piece will examine the Holy Quran and Sunnah as the textual bases, jurisprudential reasoning (usul al-fiqh) and ethical considerations supporting this preventative approach. It will contend that separating the hukm of satr from the hukm of nazar is not only jurisprudentially sound but also aligns more closely with the comprehensive wisdom (hikma) and higher objectives (maqasid) of the sharia aimed at cultivating chastity (‘iffa), preserving individual piety and maintaining societal morality by proactively reducing the occasions for temptation.

Separate responsibilities: The concession for covering and the command regarding the gaze

The primary jurisprudential weakness in the view permitting looking at the face of a non-mahram woman provided shahwa or fitna are absent lies in its frequent, often unspoken, assumption of a direct, almost reciprocal, legal connection between the ruling applicable to her act of not covering and the ruling applicable to his act of looking.

A key characteristic of Islamic legal reasoning (usul al-fiqh) is that rulings (ahkam) are specifically linked to their particular textual proofs (adilla) and underlying causes (‘ilal) or objectives (maqasid). This basic method often leads the sharia to assign distinct responsibilities and rulings to different individuals involved in related situations. For instance, the granting of a specific concession (rukhsa) to one party owing to hardship – established through its own evidence and reasoning – does not automatically override a general primary ruling (‘azima) or preventative measure (sadd adh-dhara’i‘) directed at another party, especially when different wisdoms (hikam) or potential outcomes (ma’alat) are being addressed for each distinct act and actor. The permissibility (ibaha) or concession (rukhsa) granted to one party owing to specific circumstances, consequently, does not necessarily negate or modify a prohibition (tahrim) or obligation (wujub) placed upon another party concerning a related action, particularly when that prohibition is guided by separate textual evidence or broader preventative maqasid.

In the specific case of the face, the consensus or near-consensus among classical jurists holds that it is exempt from the absolute requirement of covering (satr) that generally applies to other parts of a woman’s body. This exemption is consistently justified not as an inherent and unrestricted permission, but rather as a specific concession (rukhsa) founded upon necessity (darura or haja) and the avoidance of excessive hardship (raf‘ al-haraj). Jurists across schools explicitly stated this reasoning.

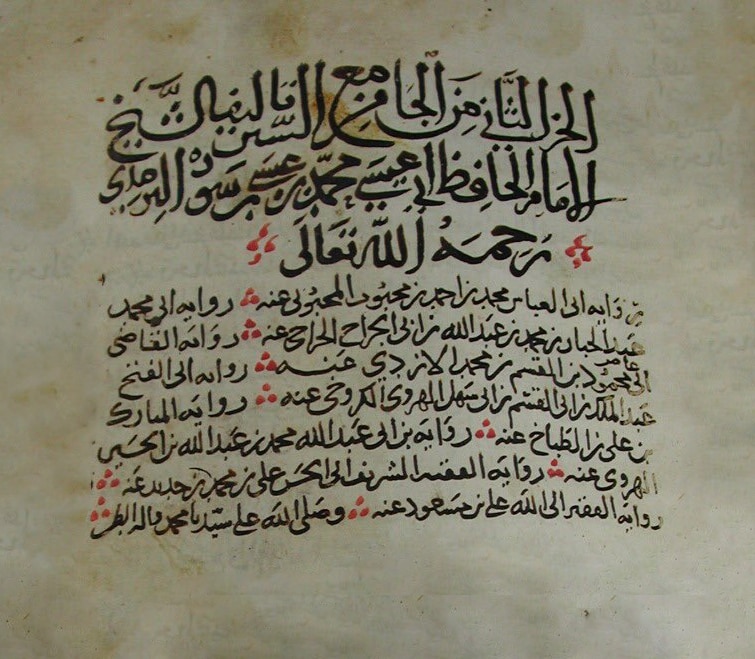

The Hanafi jurist Ibn Mawdud al-Mawsili (d. 683/1384) clearly states in al-Ikhtiyar li-ta‘lil al-Mukhtar:

لأن في ذلك ضرورة للأخذ والعطاء ومعرفة وجهها عند المعاملة مع الأجانب لإقامة معاشها

“[B]ecause in that there is necessity (darura) for giving and taking (akhdh wa-‘ata’) and knowing her face during transactions (mu‘amala) with strangers (ajanib) for establishing her livelihood.” (Ibn Mawdud al-Mawsili, al-Ikhtiyar li-ta‘lil al-Mukhtar, Cairo: Matbaʻat Mustafa al-Babi al-Halabi, 1936, Vol. 4, p. 156)

In a similar way, the Shafi‘i jurist Abu Ishaq ash-Shirazi (d. 476/1083) notes in al-Muhadhdhab:

ولأن الحاجة تدعو إلي إبراز الوجه للبيع والشراء و إلي إبراز الكف للأخذ والعطاء فلم يجعل ذلك عورة

“[A]nd because necessity (haja) calls for revealing the face for buying and selling, and for revealing the hand for giving and taking, therefore that was not made ‘awra.” (Abu Ishsaq ash-Shirazi, al-Muhadhdhab fi fiqh al-Imam ash-Shafiʻi, ed. Zakariyya ʻUmayrat, Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-ʻIlmiyya, 1995, Vol. 1, p. 124)

This reasoning, connecting the exemption directly to practical needs, is echoed within the Maliki school as well, as related by al-Maziri (d. 536/1141) citing Ibn al-Jahm (d. 329/941):

لأن بها ضرورة إلى إبداء هذين العضوين للمعاملات والأخذ والعطاء فدعت الضرورة إلى استثناء هذين العضوين

“[B]ecause there is a necessity (darura) for her to reveal these two limbs [face and hands] for transactions and giving and taking, so necessity called for the exception of these two limbs.” (Al-Maziri, Sharh at-Talqin, ed. Muhammad al-Mukhtar as-Sallami, Beirut: Dar al-Gharb al-Islami, 2008, Vol. 1, p. 471)

Our position fully acknowledges this well-established rukhsa granted to the woman, relieving her from the obligation of perpetual facial covering owing to practical requirements. It firmly holds, still, that this concession, specific to her situation and needs, does not automatically extend to create a corresponding rukhsa for an unrelated man to freely exercise his gaze upon her face. The ruling governing his act of looking (nazar) stems from independent considerations: the explicit divine command to lower the gaze (ghadd al-basar) in Surah an-Nur, Ch.24: V.31, the inherent potential of the face to be a focal point of attraction (majma‘ al-mahasin) and thus a source of fitna and the preventative legal principle of blocking the means leading to harm or sin (sadd adh-dhara’i‘).

The man’s obligation remains independent of the woman’s action; his duty to lower his gaze persists even if she uncovers her face, whether permissibly due to the concession or impermissibly.

This important separation was explicitly recognised and articulated within major schools of thought.

The relied-upon Shafi‘i position, as definitively explained by Ibn Hajar al-Haytami in his works, directly addresses the apparent logical tension. He clarifies the primary rationale for prohibiting the gaze despite the face not being ‘awra for covering in Tuhfat al-muhtaj:

وبه اندفع ما يقال: هو غير عورة فكيف حرم نظره؟ ووجه اندفاعه أنه مع كونه غير عورة نظره مظنة للفتنة أو الشهوة، ففطم الناس عنه احتياطا

“This refutes what might be said: ‘It [the face] is not ‘awra, so how is looking at it forbidden?’ The way it is refuted is that despite it not being ‘awra, looking at it is a likely cause (mazinna) of fitna or shahwa, so people were weaned off it as a precaution (ihtiyatan).” (Ibn Hajar al-Haytami, Tuhfat al-muhtaj bi-sharh al-Minhaj, Cairo: al-Maktaba al-Tijariyya al-Kubra, 1938, Vol. 7, p. 193)

This core distinction – that the concession for uncovering stems from necessity while the prohibition on looking stems from the potential for fitna – is concisely reiterated by him in al-Minhaj al-qawim:

وإنما لم يكونا عورة حتى يجب سترهما لأن الحاجة تدعوه إلى إبرازهما وحرمة نظرهما […] ليس لأن ذلك عورة بل لأن النظر إليه مظنة للفتنة

“And they [face and hands] were not made ‘awra requiring covering because necessity (al-haja) calls for their uncovering. And the prohibition of looking at them (hurmat nazaruhuma) […] is not because that [‘awra] but because looking at them is a likely cause (mazinna) of fitna.” (Ibn Hajar al-Haytami, al-Minhaj al-qawim sharh al-Muqaddima al-Hadramiyya, ed. Ahmad Shams ad-Din, Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-ʻIlmiyya, 2000, p. 115)

Furthermore, explaining in Tuhfat al-muhtaj why this preventative view is preferred despite being opposed by the majority, he highlights the distinct textual commands:

وكون الأكثرين على مقابل الصحيح لا يقتضي رجحانه لا سيما وقد أشار إلى فساد طريقتهم بتعبيره بالصحيح ووجهه أن الآية كما دلت على جواز كشفهن لوجوههن دلت على وجوب غض الرجال أبصارهم عنهن ويلزم من وجوب الغض حرمة النظر ولا يلزم من حل الكشف جوازه كما لا يخفى فاتضح ما أشار إليه بتعبيره بالصحيح

“The fact that the majority hold the view opposite to the sound or correct (as-sahih) view [i.e., prohibition] does not make it the stronger view, especially since he [an-Nawawi] indicated the weakness of their approach by using the term as-sahih. Its reasoning is that the verse [Ch.24: V.32, regarding illa ma zahara minha] – just as it indicated the permissibility of them uncovering their faces – also indicated [through the preceding verse, Ch.24: V.31] the obligation for men to lower their gazes from them. From the obligation of lowering the gaze follows the prohibition of looking, while from the permissibility of uncovering, the permissibility [of looking] does not necessarily follow, as is not hidden. Thus, what he indicated by using as-sahih becomes clear.” (Ibn Hajar al-Haytami, Tuhfat al-muhtaj bi-sharh al-Minhaj, ibid.)

Shams ad-Din ar-Ramli, another pillar of the later Shafi‘i school, echoed this exact reasoning in his Nihayat al-muhtaj, confirming its centrality to the relied-upon position. (Shams ad-Din ar-Ramli, Nihayat al-muhtaj ila sharh al-Minhaj fi l-fiqh ʻala madhhab al-Imam ash-Shafiʻi, Beirut: Dar al-Fikr, 1984, Vol. 6, p. 188)

Thus, the non-‘awra status concerning mandatory covering (satr) is conceded for the woman owing to necessity, but its direct implication for the permissibility of the man’s gaze (nazar) is decisively denied. The ruling on looking is determined independently, giving precedence to the preventative objective (maqsid) of safeguarding against fitna by addressing the act of looking itself, even when the object looked at is not mandated to be covered under all circumstances.

The divine command to lower the gaze: A proactive measure against fitna

The divine injunction central to regulating the male gaze forms a foundational element of our argument. The Holy Quran commands:

قُل لِّلْمُؤْمِنِينَ يَغُضُّوا مِنْ أَبْصَارِهِمْ وَيَحْفَظُوا فُرُوجَهُمْ ۚ ذَٰلِكَ أَزْكَىٰ لَهُمْ ۗ إِنَّ اللَّهَ خَبِيرٌ بِمَا يَصْنَعُونَ

“Say to the believing men that they restrain their looks and guard their private parts. That is purer for them. Surely, Allah is Well-Aware of what they do.” (Surah an-Nur, Ch.24: V.31)

A parallel command is given to believing women in the subsequent verse, establishing restraining the looks (ghadd al-basar) as a mutual responsibility fundamental to Islamic modesty. The opposing view often interprets this command in a reactive manner – suggesting the gaze need only be lowered or averted after shahwa is felt or when fitna is actively feared. This interpretation considerably weakens the preventative force of the verse. It presumes a level of self-awareness and control over developing desires that Islamic teachings on human nature (fitra) and the subtleties of temptation frequently caution against. Relying on subjective assessment after exposure creates a risk that the seeds of fitna may be sown.

Our position, in contrast, understands this command as fundamentally proactive and preventative. The instruction to “restrain their looks” is not simply about controlling shahwa once it arises, but about actively managing one’s sight to prevent the arousal of such feelings and to avoid situations where fitna is likely. It constitutes a primary barrier against the very means (sadd adh-dhara’i‘) that lead towards impurity. The inherent danger lies in the initiating act of looking itself, given the natural human disposition towards attraction.

The Promised Messiahas powerfully articulated this preventative understanding, rejecting any notion of permissible gazing under the guise of pure intentions:

“[G]od Almighty has not instructed us that we might freely gaze at women outside the prohibited degrees and might contemplate their beauty and observe all their movements in dancing etc. but that we should do so with pure looks. […] We have been positively commanded not to look at their beauty, whether with pure intent or otherwise, […]. We have been directed to eschew all this as we eschew carrion, so that we should not stumble. It is almost certain that our free glances would cause us to stumble sometime or the other.” (The Philosophy of the Teachings of Islam, pp. 47-48)

Expounding further on this necessary degree of aversion and contrasting it with less strict approaches, the Promised Messiahas wrote:

“Unlike the Gospel, which forbids one to look covetously and lustfully at women who are not Mahram but permits it otherwise, the Quran instructs against glancing at women under any circumstances, be it covetously or with pure intentions because one is liable to stumble on this account. In fact, your eyes should always be lowered when you confront a Non-Mahram. You should not be aware of the physical form of a woman except through an obscured sight, in the way a person’s vision is clouded in the early stages of cataract.” (Noah’s Ark, p. 46)

This interpretation views ghadd al-basar not as conditional restraint but as a comprehensive discipline involving deliberate aversion from that which is likely to tempt – primarily, the forms and faces of unrelated members of the opposite sex. The emphasis is on avoiding the stimulus altogether, aligning perfectly with the principle of sadd adh-dhara’i‘.

The precise meaning of the particle min in “their looks” (min absarihim) has been discussed by commentators. Linguistically min can indicate partition (tab‘id), i.e., restraining some of the looks and lowering some of the gaze. Yet, given the verse’s explicit aim of achieving greater purity (azka lahum) and the established Islamic principle of preventing harm by blocking its means (sadd adh-dhara’i‘), interpreting min here as primarily specifying the object from which the gaze must be averted is more aligned with the preventative purpose of the command. This perspective acknowledges the necessity of sight for daily life but demands conscious redirection away from prohibited stimuli – primarily non-mahram individuals – beyond incidental glances or established need.

This resonates strongly with the guidance of the Holy Prophetsa differentiating between the unavoidable first glance (nazrat al-faj’a) and the forbidden intentional second glance, as reported in the well-known hadith addressed to ‘Alira:

لاَ تُتْبِعِ النَّظْرَةَ النَّظْرَةَ فَإِنَّ لَكَ الأُولَى وَلَيْسَتْ لَكَ الآخِرَةُ

“Do not follow up one glance with another; the first is for you, but the second is not.” (Sunan Abi Dawud, Hadith 2149)

Fakhr ad-Din ar-Razi (d. 606/1210), in his influential Quran commentary, explicitly links the prohibition of intentional looking, even without a specific purpose or fear of fitna, to the command of ghadd al-basar and this very hadith:

فاعلم أنه لا يجوز أن يتعمد النظر إلى وجه الأجنبية لغير غرض وإن وقع بصره عليها بغتة يغض بصره، لقوله تعالى: {قل للمؤمنين يغضوا من أبصـارهم} […] ولا يجوز أن يكرر النظر إليها […] ولقوله عليه السلام: يا علي لا تتبع النظرة النظرة فإن لك الأولى وليست لك الآخرة

“Know that it is not permissible to intentionally look (yata‘ammad an-nazar) at the face of a non-mahram woman without a purpose (li-ghayr gharad), even if his gaze falls upon her suddenly, he should lower his gaze, due to the statement of Allah Almighty: {Say to the believing men that they restrain their looks}. […] And it is not permissible to repeat the glance towards her […] and due to his [the Prophet’ssa] statement: ‘O Ali, do not follow up one glance with another; the first is for you, but the second is not.’” (Mafatih al-ghayb, commentary on Surah An-Nur, Ch.24: V.31)

Ar-Razi draws a contrast: the intentional gaze undertaken without specific purpose or fear of fitna is forbidden based on the command to lower the gaze. This is distinct from looking for a valid need like marriage or testimony, which is permissible if fitna is absent. He also separately addresses looking driven by desire (shahwa), categorising it as unequivocally forbidden (mahzur) and citing prophetic warnings about the “fornication of the eye” (zina al-‘ayn). His overall analysis underscores that the primary prohibition targets the intentional gaze itself, even when shahwa or darura are absent, as a direct application of the Quranic command for restraint.

The independent force of the ghadd al-basar command is such that jurists like the famous Maliki scholar Qadi ‘Iyad (d. 544/1149), while holding the common Maliki position that face-covering (satr al-wajh) is recommended (mustahabb) not obligatory, nonetheless applied a distinct and strict ruling to the man’s gaze, affirming his separate duty:

وعلى الرجل غض بصره عنها في جميع الأحوال إلا لغرض صحيح شرعي

“[A]nd upon the man is [the obligation of] lowering his gaze from her in all circumstances, except for a valid, legitimate purpose.” (An-Nawawi, Sahih Muslim bi-sharh an-Nawawi, ed. ʻIsam as-Sababiti; Hazim Muhammad, ʻImad ʻAmir, Cairo: Dar al-Hadith, 1994, Vol. 7, p. 393)

The stance of Qadi ‘Iyad again illustrates the principle that the man’s obligation to lower his gaze operates independently of the ruling concerning the woman’s covering. This principle of separation, combined with the proactive interpretation of ghadd al-basar as a preventative measure, provides a solid foundation – across various schools of thought – for prohibiting intentional gazing at non-mahram women, irrespective of whether their faces are technically defined as ‘awra requiring covering.

Blocking the means: The principle of sadd adh-dhara’i‘ and the gaze

Central to the jurisprudential basis of our view is the principle of sadd adh-dhara’i‘, meaning literally blocking the means or pathways that lead to prohibited (haram) or harmful outcomes. This principle, recognised particularly strongly within the Maliki and Hanbali schools but operationally relevant across Sunni jurisprudence, permits the sharia to prohibit actions that, while potentially permissible (mubah) in isolation, serve as likely precursors or facilitators (dhara’i‘) to sin or social harm (mafsada). In the context of relations between genders, sadd adh-dhara’i‘ provides a sound justification for prohibiting the intentional male gaze (nazar) directed at a non-mahram woman’s face, even if that face is not technically mandated to be covered (satr) under all circumstances. The look itself is identified as a primary means leading towards fitna and the potential arousal of shahwa.

This preventative approach contrasts markedly with the opposing view’s reliance on subjective and often unreliable conditions – specifically, the assertion that looking is permissible provided the viewer ascertains within themselves an absence of shahwa or immediate fear of fitna. Our position, grounded in sadd adh-dhara’i‘, argues that such self-assessment is precarious considering the inherent weaknesses and subtleties of human nature (fitra) regarding attraction.

The grave danger of the initial, seemingly innocuous look is highlighted by Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya (d. 751/1350):

والنظر أصل عامّة الحوادث التي تصيب الإنسان، فإنّ النظرة تولّد خطرةً، ثم تولّد الخطرة فكرةً، ثم تولّد الفكرة شهوةً، ثم تولّد الشهوة إرادةً، ثم تقوى فتصير عزيمةً جازمةً، فيقع الفعل، ولا بدّ، ما لم يمنع منه مانع.

“And the gaze (nazar) is the origin (asl) of most problems (hawadith) that afflict a person. For the glance (nazra) gives birth to a fleeting thought (khatra), then the fleeting thought gives birth to a developed thought (fikra), then the thought gives birth to desire (shahwa), then desire gives birth to will (irada), which then strengthens and becomes firm resolve (‘azima jazima), and the action inevitably occurs, so long as there is no impediment to prevent it.” (Ibn al-Qayyim, ad-Da’ wa-d-Dawa’, ed. Muhammad Ajmal al-Islahi, Mecca: Dar ‘Alam al-Fawa’id, 2008, p. 350)

This step-by-step analysis reveals precisely how the gaze serves as the critical first step – the dhari‘a – on a path that leads to sin, explaining why blocking this initial means is a cornerstone of preventative Islamic ethics.

The sharia, in its wisdom, does not primarily depend on individuals successfully policing their internal states after exposure to potent stimuli; rather, it aims to minimise exposure to such stimuli in the first instance.

Furthermore, the mere existence of scholarly disagreement (khilaf) on the permissibility of looking without shahwa does not automatically grant license to choose the more lenient view based on personal inclination. As established by consensus (ijma‘) among scholars, khilaf itself is not a proof (hujja), and the obligation remains to follow the ruling supported by the strongest evidence and alignment with broader sharia principles, such as precaution and blocking the means to harm (sadd adh-dhara’i‘). To selectively adopt a less precautionary view simply because it exists within the spectrum of opinions, especially in matters prone to temptation, risks undermining the preventative objectives of the sharia and potentially following personal desire (hawa) rather than sound evidence.

The Promised Messiahas sternly highlighted this inherent human vulnerability and the inadequacy of relying solely on managing intent after the fact:

“It should be kept in mind that as the natural condition of man, which is the source of his passions, is such that he cannot depart from it without a complete change in himself, his passions are bound to be roused, or in other words put in peril, when they are confronted with the occasion and opportunity for indulging in this vice. […] There can be no doubt that unrestrained looks become a source of danger. If we place soft bread before a hungry dog, it would be vain to hope that the dog should pay no attention to it. Thus God Almighty desired that human faculties should not be provided with any occasion for secret functioning and should not be confronted with anything that might incite dangerous tendencies.” (The Philosophy of the Teachings of Islam, pp. 47-48)

By addressing the objective risk inherent in the act of gazing – recognising its power as an “occasion and opportunity” that naturally rouses dormant passions – the principle of sadd adh-dhara’i‘ implements the preventative wisdom described here. It aims to “close the door” (hasm al-bab) to temptation before it can fully manifest, rather than depending solely on the subjective state of the gazer after exposure.

This preventative rationale, grounding the prohibition in the fear of fitna, especially concerning the face as the majma‘ al-mahasin, was clearly articulated even by classical Hanafi scholars like as-Sarakhsi (d. 483/1090) when laying out the potential bases for such a ruling. He explained this logic as:

فدل أنه لا يباح النظر إلى شيء من بدنها، ولأن حرمة النظر لخوف الفتنة وعامة محاسنها في وجهها فخوف الفتنة في النظر إلى وجهها أكثر منه إلى سائر الأعضاء

“[T]hus, it indicates that looking at any part of her body is not permitted (la yubahu n-nazaru ila shay’in min badaniha), [this is argued] because the prohibition of looking (hurmat an-nazar) is due to fear of fitna, and most of her beauty (‘ammat mahasinuha) is in her face, so the fear of fitna from looking at her face is greater than from [looking at] other parts.” (As-Sarakhsi, Kitab al-Mabsut, Beirut: Dar al-Ma‘rifa, 1989, Vol. 10, p. 152)

While as-Sarakhsi, representing the Hanafi school, ultimately gave precedence to evidence indicating a specific rukhsa for looking at the face without desire, his articulation of the fitna-based reasoning itself highlights its validity as a jurisprudential principle for prohibiting the gaze.

Such a proactive stance finds resonance in the commentaries on the very verses dealing with women’s adornment. For instance, regarding the interpretation that “what is apparent thereof” (Surah An-Nur, Ch.24: V.32) refers to the face and hands, Tafsir al-Jalalayn notes:

فيجوز نظره لأجنبي إن لم يخف فتنة في أحد وجهين والثاني يحرم لأنه مظنة الفتنة ورجح حسما للباب

“According to one of two views (wajhayn), looking at them by a non-mahram is permissible if there is no fear of fitna. The second [view] is that it is forbidden because it is a likely cause (mazinna) of fitna, and this [view] was preferred (rujjiha) in order to close the door (hasman li-l-bab).” (Tafsir al-Jalalayn, commentary on An-Nur, Ch.24: V.32)

This preference for prohibition, justified by the potential for fitna and the principle of closing the door, even while acknowledging the view permitting uncovering, strongly supports the application of sadd adh-dhara’i‘ to the gaze itself.

It aligns with the approach advocated by influential classical jurists in similar contexts.

Al-Juwayni, the leading Shafi‘i scholar of his era, articulated this logic when justifying the prohibition on looking, comparing it to the general prohibition on seclusion (khalwa) with a non-mahram, which applies broadly without examining specific intentions in every case:

واللائق بمحاسن الشريعة حسم الباب وترك تفصيل الأحوال، كتحريم الخلوة تعمّ الأشخاص والأحوال

“[A]nd what befits the beauties (mahasin) of the sharia is closing the door (hasm al-bab) and avoiding the detailed assessment of circumstances, just like the prohibition of seclusion (khalwa), which applies generally to persons and situations [if non-mahram].” (Al-Juwayni, Nihayat al-matlab fi dirayat al-madhhab, ed. ʻAbd al-ʻAzim Mahmud ad-Dib, Jeddah: Dar al-Minhaj, 2007, Vol. 12, p. 31)

Al-Ghazali (d. 505/1111), discussing impediments that make listening forbidden, draws a comparison with the ruling on looking, explicitly stating the preventative principle applied to the face:

أحدهما أن الخلوة بالأجنبية والنظر إلى وجهها حرام سواء خيفت الفتنة أو لم تخف لأنها مظنة الفتنة على الجملة فقضى الشرع بحسم الباب من غير التفات إلى الصور

“One of the two [principles] is that seclusion (khalwa) with a non-mahram woman and looking at her face (an-nazar ila wajhiha) is forbidden (haram), whether fitna is feared or not, because it is a likely cause of fitna (mazinnat al-fitna) in general. Thus, the sharia dictated closing the door (hasm al-bab) without regard to specific situations.” (Al-Ghazali, Ihya’ ‘ulum ad-din, Beirut: Dar al-Ma ‘rifa, 1982, Vol. 2, p. 281)

This statement clearly categorises looking at the face under the principle of hasm al-bab, prohibiting it generally due to its potential for fitna, irrespective of the subjective assessment of risk in individual cases, aligning directly with the preventative approach.

This preventative perspective extends to prohibiting looking without a valid reason or sustaining the gaze beyond the initial glance, even if desire is claimed absent.

The Shafi‘i jurist al-‘Imrani (d. 558/1163) states:

وإذا أراد الرجل أن ينظر إلى امرأة أجنبية منه من غير سبب فلا يجوز له ذلك، لا إلى العورة، ولا إلى غير العورة

“And if a man intends (arada) to look at a non-mahram woman without reason (min ghayri sabab), that is not permissible for him (fa-la yajuzu lahu dhalik), neither towards the ‘awra, nor towards other than the ‘awra.” (Al-‘Imrani, Al-Bayan fi madhhab al-Imam ash-Shafi‘i, ed. Qasim Muhammad an-Nuri, Jeddah: Dar al-Minhaj, 2000, Vol. 9, p. 125)

Similarly, the Hanbali position, as related by Ibn Qudama (d. 620/1223), prohibits looking without cause:

فأما نظر الرجل إلى الأجنبية من غير سبب، فإنه محرم إلى جميعها، في ظاهر كلام أحمد. قال أحمد: لا يأكل مع مطلقته، هو أجنبي لا يحل له أن ينظر إليها

“As for a man looking at a non-mahram woman without reason (min ghayri sabab), then it is forbidden (muharram) [to look] at all of her, according to the apparent statement (zahir kalam) of Ahmad. Ahmad said: He should not eat with his divorced wife; he is a stranger (ajnabi), it is not permissible (la yahillu) for him to look at her.” (Ibn Qudama, Al-Mughni, ed. Mahmud ʻAbd al-Wahhab Fayid; Muhammad ʻAbd al-Qadir ʻAta, Cairo: Maktakabat al-Qahira, 1969, Vol. 7, p. 102)

The Maliki scholar Ibn ‘Abd al-Barr (d. 463/1071) also emphasises the prohibition on looking, even extending the caution to mahrams:

ولا يجوز ترداد النظر وإدامته لامرأة شابة من ذوي المحارم أو غيرهن إلا عند الحاجة إليه أو الضرورة في الشهادة ونحوها

“And it is not permissible (la yajuz) to repeat the glance (tardad an-nazar) and sustain it (idamatuhu) towards a young woman (imra’a shabba), whether from mahrams or others, except for need (haja) or necessity (darura) in testimony and the like.” (Ibn ‘Abd al-Barr, Kitab Al-Kafi fi fiqh ahl al-Madina al-Maliki, ed. Muhammad Muhammad Ahid Wuld Madik al-Muritani, Riyadh: Maktabat ar-Riyad al-Haditha, 1980, Vol. 2, p. 1136)

These statements underscore that the prohibition is not merely reactive to subjective feelings but involves actively avoiding unnecessary looking as a means of preventing fitna.

The opposing view’s reliance on the absence of shahwa is further weakened because the term, as defined by jurists, often encompasses more than just overt physical arousal. It can refer simply to inclination or attraction.

Illustrating this point, the renowned Hanafi scholar Ibn ‘Abidin (d. 1252/1836) cites the definition given by ‘Abd al-Ghani an-Nabulsi (d. 1143/1731), where shahwa involves the state where:

يتحرك قلب الإنسان ويميل بطبعه إلى اللذة

“[T]he person’s heart is stirred and inclines by its nature towards pleasure (ladhdha)”. (Ibn ‘Abidin, Hashiyat Radd al-muhtar ʻala ad-Durr al-mukhtar, Cairo: Shirkat Maktab wa-Matbaʻat Mustafa al-Babi al-Halabi wa-Awladih, 1966, Vol. 1, p. 407)

Because shahwa includes such subtle internal states – the mere inclination of the heart – it becomes exceptionally difficult to reliably ascertain its absence. This renders the condition absence of shahwa a precarious and insufficient safeguard for permitting the gaze.

Arguments citing the corruption of the times (fasad az-zaman) were employed by some later jurists, particularly within the Hanafi school, not only to justify strengthening the woman’s obligation to cover her face, but also to restrict the man’s gaze beyond the default ruling.

While the earlier Hanafi position permitted looking at the face if there was certainty of no shahwa, later Hanafi scholars like Shams ad-Din al-Quhistani (d. 953/1546) stated:

وأما في زماننا فمنع من الشابة

“As for our time, [looking at] a young woman is forbidden.” (Shams ad-Din al-Quhistani, Jami‘ ar-Rumuz, ed. Kabir ad-Din Ahmad, Calcutta: Mazhar al-‘Ajayib, 1858, p. 530)

Al-Haskafi (d. 1088/1677) clarifies the reason:

لا لأنه عورة بل لخوف الفتنة

“Not because it is ‘awra, but due to fear of fitna.” (Al-Haskafi, ad-Durr al-mukhtar, ed. ‘Abd al-Mun‘im Khalil Ibrahim, Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyya, 2002, p. 58).

This demonstrates the direct application of sadd adh-dhara’i‘ principles to the man’s gaze due to perceived societal conditions. The core relevance of sadd adh-dhara’i‘ for our view pertains directly to the independent prohibition on the man’s gaze. This principle provides a fundamental, objective legal basis rooted in preventative wisdom, applicable even outside conditions of extreme societal decline, although such conditions might certainly accentuate its perceived necessity.

Sadd adh-dhara’i‘, consequently, offers a compelling jurisprudential foundation for prohibiting the intentional gaze at a non-mahram woman’s face as a primary preventative measure, shifting the focus from the unreliable subjective state of the viewer to the objective potential of the act itself to serve as a means towards fitna.

Evidence from the Sunnah: The Khath‘amiyya incident and the principle of exceptions

Proponents of the view permitting looking without shahwa often cite specific incidents from the Sunnah, arguing they demonstrate a baseline permissibility for looking at non-mahram women. Principal among these is the well-known encounter involving the Holy Prophetsa, his cousin al-Fadl b. al-‘Abbasra and a woman from the Khath‘am tribe during the Farewell Pilgrimage. A careful examination of this and similar reports, alongside the established jurisprudential principle that specific allowances (rukhas) indicate a general prohibition, reveals that these narratives actually support the preventative position.

The Khath‘amiyya incident, rather than affirming a right to look innocently, powerfully illustrates the Prophet’ssa proactive implementation of sadd al-dhara’i‘ regarding the gaze. As al-Fadlra, described as a handsome young man, began looking intently at the young woman asking the Prophetsa a question, the Prophetsa did not merely counsel him about intent; he physically intervened. The detailed narration clarifies his action and explicit reasoning:

فالتفت النبي صلى الله عليه وسلم والفضل ينظر إليها، فأخلف بيده فأخذ بذقن الفضل، فعدل وجهه عن النظر إليها […] فقال له العباس: يا رسول الله، لم لويت عنق ابن عمك؟ قال: رأيت شاباً وشابة، فلم آمن الشيطان عليهما

“The Prophetsa turned while al-Fadl was looking at her, so he put his hand behind al-Fadl’s chin and turned his face away from looking at her. […] Al-‘Abbas said to him, ‘O Messenger of Allah, why did you twist your cousin’s neck?’ He replied, ‘I saw a young man and a young woman, and I did not trust Satan regarding them.’” (Sunan at-Tirmidhi, 885)

The Prophet’ssa direct physical intervention and his stated reason – “I did not trust Satan regarding them” (lam aman ash-shaytan ‘alayhima) – highlight the perceived inherent risk of mutual gazing between young, unrelated individuals, irrespective of their initial intentions. His action was preventative, aimed at averting potential fitna before it could arise thus aligning perfectly with the principle of blocking the means.

Hadith commentators like Qadi ‘Iyad noted that the Prophetsa did not explicitly order the woman to cover her face in that instance, which he used to argue face-covering was not universally obligatory. (Qadi ‘Iyad, Ikmal al-mu‘lim bi-fawa’id Muslim, ed. Yahya Ismaʻil, Mansoura: Dar al-Wafaʼ li-t-Tibaʻa wa-n-Nashr wa-t-Tawziʻ, 1998, Vol. 4, p. 440)

This observation pertains to her satr, not the ruling on al-Fadl’sra nazar. The Prophet’ssa focus was on immediately curtailing the man’s gaze owing to the evident risk.

The very existence of specific, enumerated permissions (rukhas) within the sharia for men to look at non-mahram women under conditions of defined need (haja or darura) serves as strong evidence that the general rule (asl) is prohibition. Islamic jurisprudence operates on the principle that exceptions are made only where a general rule exists. Indeed, the exception proves the rule. If looking without shahwa were generally permissible, there would be little need to explicitly permit it under specific circumstances like providing testimony (shahada), administering medical treatment (‘ilaj), engaging in necessary transactions (mu‘amala) or viewing a prospective spouse (khitba). The careful delineation of these exceptions across the legal schools signifies that looking outside these boundaries is generally disallowed.

Numerous Maliki jurists, even those who permitted looking without shahwa more broadly than Shafi‘is or Hanbalis, often restricted looking at young women (shabba) precisely to these situations of need. Ibn Rushd al-Jadd (d. 520/1126), one of the most important and influential Maliki jurists of all times, for instance, stated:

ولا يجوز له أن ينظر إلى الشابة إلا لعذر من شهادة أو علاج أو عند إرادة نكاحها

“And it is not permissible for him to look at the young woman (shabba) except for a valid reason (‘udhr) such as testimony, medical treatment or when intending to marry her.” (Ibn Rushd al-Jadd, Al-Muqaddimat al-mumahhidat, ed. Muhammad Hajji, Beirut: Dar al-Gharb al-Islami, 1988, Vol. 3, p. 460)

This perspective, restricting the gaze upon a young woman solely to cases of necessity, was echoed by later Maliki authorities such as Ibn Shas (d. 616/1219) and Ibn al-Hajib (d. 646/1249). (Cf. Ibn Shas, ʻIqd al-jawahir ath-thamina fi madhhab ʻalim al-Madina, ed. Hamid b. Muhammad Lahmar, Beirut: Dar al-Gharb al-Islami, 2003, Vol. 3, p. 1305; Ibn al-Hajib, Jami‘ al-ummahat, ed. Abu ʻAbd ar-Rahman al-Akhdar al-Akhdari, Damascus; Beirut: al-Yamaya li-t-Tibaʻa wa-n-Nashr wa-t-Tawziʻ, 2000, p. 569)

The statement of Qadi ‘Iyad, previously cited, limiting permissible looking to “a valid, legitimate purpose” (gharad sahih shar‘i) further reinforces this point. The specification of valid purposes implies the absence of general permission.

Rather than supporting a general permissibility, the careful legal framework surrounding exceptions for looking strongly indicates that the default ruling, derived from the command for ghadd al-basar and the principle of sadd adh-dhara’i‘, is one of prohibition outside of clearly defined necessity.

The argument from prayer (salah) and the distinction between rulings

A frequent argument put forward by proponents of the permissive view utilises the established agreement (ijma‘) within Islamic jurisprudence that a woman is permitted, and indeed generally required, to leave her face uncovered during the ritual prayer (salah). As articulated by the Maliki scholar Ibn ‘Abd al-Barr:

لإجماع العلماء على أن للمرأة أن تصلي المكتوبة ويداها ووجهها مكشوف ذلك كله منها تباشر الأرض به، وأجمعوا على أنها لا تصلي متنقبة ولا عليها أن تلبس قفازين في الصلاة، وفي هذا أوضح الدلائل على أن ذلك منها غير عورة

“[T]he agreement (ijma‘) of the scholars is that it is for a woman to perform the obligatory prayer with her hands and face uncovered, pressing them directly to the ground [in prostration]. They also agree she should not pray wearing a niqab (mutanaqqiba) nor wear gloves (quffazayn) during prayer. In this lies the clearest evidence that these parts are not ‘awra [in this context]”. (Ibn ‘Abd al-Barr, at-Tamhid li-ma fi l-Muwattaʼ min al-maʻani wa-l-asanid, ed. Saʻid Ahmad Aʻrab; Muhammad al-Fallah, Rabat: Wizarat al-Awqaf wa-sh-Shuʼun al-Islamiyya, Vol. 6, p. 365)

From this agreement regarding the specific context of prayer, the opposing argument infers a broader principle: if the face is not ‘awra for the correctness (sihha) of prayer and can be exposed during this sacred act, it cannot be considered intrinsically forbidden (haram) to look at outside of prayer, provided conditions of shahwa or fitna are absent.

The early Maliki scholar Qadi Isma‘il b. Ishaq (d. 282/896) presented this line of reasoning explicitly, arguing that since covering the face is not required in prayer, this indicates it is permissible for strangers to see:

قد جاء التفسير ما ذكر، والظاهر والله أعلم – يدل على أنه الوجه والكفان، لأن المرأة يجب عليها أن تستر فى الصلاة كل موضع منها إلا وجهها وكفيها، وفى ذلك دليل أن الوجه والكفين يجوز للغرباء أن يروه من المرأة

“The interpretation [of illa ma zahara minha] has come as mentioned [i.e., face and hands], and the apparent meaning – and Allah knows best – indicates that it refers to the face and hands, because the woman is obligated to cover every part of herself in prayer except her face and hands. And in that is evidence (dalil) that the face and hands are permissible (yajuz) for strangers (ghuraba’) to see from the woman”. (Ibn Battal, Sharh Sahih al-Bukhari, ed. Abu Tamim Yasir b. Ibrahim, Riyadh: Maktabat ar-Rushd, 2003, Vol. 9, p. 21)

This line of reasoning fails to appreciate the distinction made by jurists between the specific requirements for covering during the act of prayer (‘awrat as-salah) and the separate ruling governing what is permissible or prohibited for a non-mahram man to look at (‘awrat an-nazar) – in general social interactions. The ruling allowing the face to be uncovered during prayer is specific to that act of worship (‘ibada). Its rationale is linked not only to practical necessities like letting the forehead directly touch the ground during prostration (sujud), but also to the interpretation of scriptural exceptions specifically within the framework of worship. Covering the face during prayer is often explicitly discouraged (makruh) or even considered invalidating by some, indicating a specific ritual requirement separate from general rules of modesty and interaction.

There is, in fact, a scholarly consensus (ijma‘) on the necessity of differentiating between types of ‘awra based on context. (ʻAbd al-ʻAziz b. Marzuq at-Turayfi, Al-Hijab fi sh-sharʻ wa-l-fitra, Riyadh: Maktabat Dar al-Minhaj, 2015, p. 80)

This jurisprudential distinction is key: the parts that must be covered for prayer validity define the minimal ‘awrat as-salah. In contrast, the prohibition related to looking (‘awrat an-nazar) addresses what is forbidden for an unrelated person to intentionally look at, primarily because the act of looking itself is considered a source of fitna (mazinnat al-fitna). This prohibition on looking extends to parts, like the face, which are permissible to uncover during prayer, i.e., not part of ‘awrat as-salah. Confusing these distinct legal categories and their respective rationales leads to flawed conclusions.

Numerous jurists across different schools explicitly articulated this distinction.

The contemporary Saudi scholar ‘Abd ar-Rahman al-Barrak concisely defines this specific concept:

عورةُ النَّظرِ هي ما لا يجوز النَّظرُ وإنْ لم يجبْ سَتْرُهَا

“The ‘awra related to looking (‘awrat an-nazar) is that which it is impermissible to look at, even if it is not obligatory to cover it.” (“Ma l-faraq bayna ‘awrat an-nazar wa-‘awrat as-satr”, albarrak.com, 25 December 2017)

This clear definition encapsulates the principle demonstrated by classical scholars cited below.

al-Baydawi (d. 685/1286), commenting on the interpretation that ma zahara minha refers to the face, stated:

والأظهر أن هذا في الصلاة لا في النظر فإن كل بدن الحرة عورة لا يحل لغير الزوج والمحرم النظر إلى شيء منها إلا لضرورة

“And the most apparent [interpretation] is that this [exemption] is regarding prayer (fi s-salah), not regarding looking (la fi n-nazar), for indeed the entire body of a free woman is ‘awra [in the context of nazar], it is not permissible for anyone other than the husband or mahram to look at any part of her except out of necessity (darura)”. (Anwar at-tanzil, commentary on Surah an-Nur, Ch.24: V.32)

The Shafi‘i scholar Zakariyya al-Ansari (d. 926/1520) stated clearly:

(وعورة الحرة في الصلاة، وعند الأجنبي) ولو خارجها (جميع بدنها إلا الوجه، والكفين) […] وإنما لم يكونا عورة [في الصلاة وعند الأجنبي]؛ لأن الحاجة تدعو إلى إبرازهما، وإنما حرم النظر إليهما؛ لأنهما مظنة الفتنة.

“(The ‘awra of a free woman in prayer and in the presence of a non-mahram man), even outside prayer, (is her entire body except the face and hands) […]. These are not ‘awra [requiring covering] because necessity calls for their uncovering. However, looking at them [the face and hands] is forbidden because they are likely sources of fitna (mazinnat al-fitna).” (Zakariyya al-Ansari, Asna al-matalib, Cairo: Dar al-Kitab al-Islami, n.d., Vol. 1, p. 176)

This distinction is further emphasised by Muhammad b. Sulayman al-Kurdi (d. 1194/1780), a prominent Islamic jurist and teacher of the Salafi school of thought in the Ottoman Empire, specifically Damascus, who held the position of Grand Mufti:

هذا لا ينافي قول من قال إن عورتها عند الأجانب جميع بدنها، لأن حرمة نظر الأجانب إلى الوجه والكفين إنما هي من حيث أن نظرهما مظنة للشهوة لا من حيث كونهما عورة

“This does not contradict the statement of those who say her ‘awra in the presence of non-mahrams is her entire body, because the prohibition of non-mahrams looking at the face and hands is only from the perspective that looking at them is a likely cause of desire (mazinna li-sh-shahwa), not from the perspective of them being ‘awra [for covering].” (Al-Kurdi, al-Hawashi al-madaniyya ʻala Sharh al-Muqaddima al-Hadramiyya, ed. Muhammad al-Sayyid ʻUthman, Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-ʻIlmiyya, 2013, Vol. 1, p. 494)

This distinction is further emphasised by the later Shafi‘i commentator, Sulayman al-Bijirmi (d. 1221/1806), in his supercommentary on al-Khatib ash-Shirbini’s commentary:

أما عورتها خارج الصلاة بالنسبة لنظر الأجنبي إليها فهي جميع بدنها حتى الوجه والكفين، ولو عند أمن الفتنة

“As for her ‘awra outside of prayer with respect to a non-mahram man looking at her, it is her entire body including the face and hands, even in case of the absence of fitna (law ‘inda amn al-fitna).” (Sulayman al-Bijirmi, Bijirmi ‘ala al-Khatib, Beirut: Dar al-Fikr, 1995, Vol. 1, p. 450)

This explicitly defines the ‘awra for looking as encompassing the entire body, including the face and hands, and confirms the prohibition applies even if one presumes the absence of fitna, clearly separating it from the ruling specific to prayer.

Taqi ad-Din as-Subki (d. 756/1355) explicitly articulated this stricter scope for looking:

الأقرب إلى صنيع الأصحاب أن وجهها وكفيها عورة في النظر

“The closest to the methodology (sani‘) of the companions [Shafi‘i scholars] is that her face and hands are ‘awra with respect to looking (fi n-nazar).” (Ibn Hajar al-Haytami, Tuhfat al-muhtaj bi-sharh al-Minhaj, ibid.)

This established distinction led scholars like Nur ad-Din ‘Ali az-Ziyadi (d. 1024/1615), a Shafi‘i jurist and Shaykh al-Azhar, to explicitly categorise different types of ‘awra based on context:

عرف بهذا التقرير أن لها ثلاث عورات عورة في الصلاة وهو ما تقدم وعورة بالنسبة لنظر الأجانب إليها جميع بدنها حتى الوجه والكفين على المعتمد وعورة في الخلوة وعند المحارم كعورة الرجل

“It is known from this explanation that she [the woman] has three [types of] ‘awra: ‘awra in prayer (salah), which was discussed earlier; ‘awra with respect to the gaze of non-mahrams (nazar al-ajanib) towards her, which is her entire body including the face and hands according to the relied-upon view (‘ala al-mu‘tamad); and ‘awra in seclusion (khalwa) and in the presence of mahrams, which is like the ‘awra of a man.” (Al-‘Abbadi; Ash-Shirwani, Hawashi ash-Sharwani wa-l-‘Abbadi ‘ala Tuhfat al-muhtaj bi-sharh al-Minhaj, ed. Anas ash-Shami, Cairo: Dar al-Hadith, 2016, Vol. 2, p. 364)

This distinction was not limited to the Shafi‘is.

Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya (d. 751/1350), a prominent Hanbali scholar, noted:

العورة عورتان: عورة في النظر، وعورة في الصلاة، فالحرة لها أن تصلي مكشوفة الوجه والكفين، وليس لها أن تخرج في الأسواق ومجامع الناس كذلك.

“The ‘awra is of two types: ‘awra concerning looking (fi n-nazar) and ‘awra concerning prayer (fi s-salah). The free woman may pray with her face and hands uncovered, but she may not go out in the marketplaces and public gatherings like that.” (Ibn al-Qayyim, I‘lam al-muwaqqi‘in ‘an Rabb al-‘Alamin, ed. Abu ʻUbayda Mashhur b. Hasan Al Salman, Dammam: Dar Ibn al-Jawzi, 2002, Vol. 3, p. 285)

In a similar vein, the Maliki jurist Ibn al-Qattan al-Fasi (d. 628/1231), while analysing the different viewpoints within his own school regarding looking at the face and the basis for its permissibility or prohibition, acknowledged the possibility of this very separation:

وهذا الإستقراء في أنه ليس بعورة صحيح، ولكن قد يمكن أن يقال: إنه ليس بعورة فيجوز النظر إليه، وأن يقال: [إنه] ليس بعورة ولكن لا يجوز النظر إليه.

“And this inference (istiqra’) that it [the face] is not ‘awra is correct. But it is possible to say: it is not ‘awra, so looking at it is permissible; and it is possible to say: [it] is not ‘awra, but looking at it is not permissible.” (Ibn al-Qattan, Ihkam an-nazar fi ahkam an-nazar bi-hassat al-basar, ed. Idris as-Samadi, Damascus: Dar al-Qalam, 2012, p. 180)

Ibn al-Qattan’s acknowledgement points to an important distinction sometimes observed even among Maliki scholars: the rules about what a woman must cover (‘awrat al-satr) are separate from the rules about what a man may look at (‘awrat an-nazar). Just because something, like the face, may not require covering does not automatically mean looking at it is allowed, nor does it automatically mean it is forbidden – they are treated as two separate legal issues. This insight is valuable because it questions the idea that all Malikis effectively agreed on allowing the gaze under certain conditions, even if they disagreed on the reasoning. If the link between allowed to be uncovered and allowed to be looked at is broken, as Ibn al-Qattan suggests is possible, then the claim of unified agreement on the practical outcome cannot be sustained.

The agreement regarding the face in the specific context of prayer does not automatically dictate the ruling for a man’s gaze outside of prayer, particularly in the broader societal sphere where the potential for fitna is different and often greater. The requirements for satr during salah address the correctness of the worship itself under specific ritual conditions, while the rules for nazar are governed independently by the command for ghadd al-basar and the principle of sadd adh-dhara’i‘, aimed at preventing fitna in social interactions. The different objectives and potential risks in each context allow for, and indeed point to the need for, separate rulings.

Preventative wisdom: Safeguarding piety and society

The argument presented by the opposing view – that the established non-‘awra status of a woman’s face regarding mandatory covering directly implies permissibility for a non-mahram man to look at it, provided shahwa or fear of fitna are subjectively deemed absent – constitutes an interpretation that oversimplifies the matter unduly and carries potential risks regarding Islamic legal principles. This perspective, while perhaps appearing straightforward, does not sufficiently consider the varied aspects of sharia rulings concerning modesty and interaction between genders. It neglects the important principle, evident throughout jurisprudential methodology, that distinct rulings often apply to different agents based on separate textual commands, underlying causes and preventative objectives.

Specifically, the permissive argument diminishes the independent and proactive strength of the divine command for lowering the gaze (ghadd al-basar), interpreting it merely as a reactive measure rather than a fundamental preventative discipline that targets even the intentional gaze undertaken without specific purpose or perceived fitna, as highlighted by commentators like ar-Razi.

It neglects the deep wisdom contained within the principle of blocking the means (sadd al-dhara’i‘), a principle illustrated by Ibn al-Qayyim’s analysis of the glance as the origin of subsequent sinful thoughts and actions and invoked by jurists like al-Juwayni and al-Ghazali to justify “closing the door” (hasm al-bab) by prohibiting the gaze at the face irrespective of subjective assessments.

It further relies on a narrow definition of shahwa that overlooks the subtle inclination of the heart identified by some jurists. It incorrectly construes important narrative evidence, such as the Khath‘amiyya incident, which actually demonstrates prophetic intervention to prevent the gaze owing to perceived risk, and it fails to grasp the legal purpose of specific allowances (rukhas) for looking under necessity, whose very existence points to a general rule of prohibition.

Lastly, it inappropriately mixes the specific rulings governing satr within the distinct ritual context of prayer (salah) with the broader requirements of modesty and gaze control in general social life, failing to appreciate the explicit distinction made by numerous scholars between ‘awrat as-satr, ‘awrat as-salah and the broader scope of ‘awrat an-nazar.

The position advocated herein – aligning with the preventative philosophy articulated by the Promised Messiahas, the relied-upon stance of the Shafi‘i school, the dominant Hanbali view and the cautionary approach reflected in the reasoning of later Hanafi authorities concerned with fasad az-zaman – maintains a necessary separation between the ruling on her covering and the ruling on his looking.

The strength of the Shafi‘i position prohibiting the gaze even without desire or fear of fitna is underscored by leading figures like an-Nawawi designating it as the sound or correct view and later authorities like Ibn Hajar al-Haytami, ar-Ramli and others confirming it as the relied-upon view for fatwa, despite acknowledging that the opposing view permitting looking without shahwa or fitna was held by a majority of earlier scholars. This preference was explicitly based on the strength of the evidence supporting prohibition and the principle of precaution, as articulated by scholars like as-Subki.

It recognises that the sharia grants women a concession (rukhsa) regarding facial covering owing to practical hardship and necessity. At the same time, it imposes a distinct obligation (‘azima) on men and women to proactively lower their gaze (ghadd al-basar) from that which is likely to incite temptation, applying the principle of sadd adh-dhara’i‘ to the act of looking itself.

Furthermore, it is important to uphold established jurisprudential methodology when navigating areas of scholarly difference (khilaf). The mere existence of a more lenient opinion within the spectrum of valid ijtihad does not automatically render it permissible to adopt, particularly when it appears to contradict clearer primary texts or established preventative principles like sadd adh-dhara’i‘. Scholars have consistently warned against specifically seeking out concessions or choosing opinions based on personal ease or desire rather than the strength of the evidence.

As Ahmad b. Hanbal is reported to have cautioned, selectively adopting the easiest opinion from various schools on different matters could lead to accumulating “all evil” (ijtima‘ ash-sharr).

Similarly, al-Awza‘i warned that taking the anomalous opinions (nawadir) of scholars could lead one out of Islam.

The principle remains to follow the ruling best supported by the Quran, Sunnah and sound jurisprudential reasoning, giving due weight to preventative measures established by the sharia.

This preventative framework, grounded in the proactive command for ghadd al-basar and the principle of sadd adh-dhara’i‘, acknowledges the realities of human nature and gives precedence to safeguarding piety by minimising exposure to temptation.

It reflects a greater degree of precaution that serves the higher aims (maqasid) of the sharia: the cultivation of chastity (‘iffa), the purification of hearts (tazkiya), the protection of lineage and family integrity (hifz an-nasab) and the preservation of a morally sound society. By prohibiting the intentional gaze outside of defined necessity, even when the face itself is not mandated to be covered, Islamic law implements a deep wisdom, safeguarding both individual piety and collective well-being from the subtle but strong dangers of unrestricted visual interaction.