Asif M Basit, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre, London

Polygamy remains one of the permissible practices of Islam brought under strict scrutiny by the modern Western world. The primary criticism rests on modern moral standards which again are set by none else but the West.

Before looking at how the provision of polygamy emerged in Islam, it is important to understand the moral standards of pre-Islamic Arabia – a melting pot of various religions and their ethics, and also of the absence of both.

Where men would feel free to take as many women as they liked, even without any legal marital contract, Islam emerged with strict rules on marriage and the maximum number of women that could be taken into a legal matrimonial contract at a time.

This is agreed by historians as one of the revolutionary social standards set by Islam in its contemporaneous world.

In a time when peace was only established through military conflicts, scores of female prisoners of war posed another threat to society by being seen as a class that was a free-for-all commodity. Where pre-Islamic society saw illegitimate births and diminished parental responsibility through this class of women, Islam provided a legal framework for men to take ownership of such women by upholding their rights, should a man decide to take one or more of them as concubines.

Hence it can justifiably be said that Islam, through polygamy, imposed restrictions on a primitive society that thrived on free-sex, just as much as the modern Western world does. This leaves one wondering whether modern society is opposed to polygamy as a mode of free-sex, or, on the contrary, a restriction on any such modes.

A society where men and women can cohabit without any legal contract and feel free to have children, and part their ways when they like can only be critical of Islamic polygamy for the reason that it restricts, and not that it allows such freedom.

That Islam takes into account the psyche of men and women in its permissibility of polygamy is another debate which is important to this brief study. The stark difference in the functionality of male and female sex-drives is a factor that cannot be ignored when discussing polygamy in its historical context, just as much as it cannot be ignored with reference to modern society.

Even in early Islam, permission and injunction were always weighed in to maintain the equilibrium of the social structure. Mutah, or temporary marriage, remained permissible in Islam but was forbidden at or around the time of the Battle of Khyber (c. 628CE).

Similarly, polygamy was never seen as an injunction for Muslim men, but more as a permission to facilitate the shunning of moral vices that could potentially develop into social evils. The Holy Quran, when issuing permissibility, clarifies that upholding justice among all wives is paramount, and also that this justice is not an easy goal to achieve.

As mentioned earlier, conflict and war remained a permanent feature of the early days of Islam. While women were not permitted to actively participate in combat, men remained away from home on military expeditions. This meant that they were away from their wives for long periods of time. No other means of satisfying carnal desires were permissible in Islamic teachings other than by way of nikah, or announcement of marital contract, between a man and a woman.

However, in the time of Hazrat Umarra, the Second Caliph of Prophet Muhammadsa, it was felt that married men and women should not be kept apart for longer than four months. Tradition has it Hazrat Umarra, having overheard a sad song of a woman longing for her husband who was at war, did not hesitate to approach his own daughter Hafsah and ask how long a woman could reasonably live without her husband. It was upon her reply that he decreed that men were not to be kept away on the battlefield for longer than four months.

However, marriages of Muslim men, including those of the Prophetsa himself, have remained a favourite area of debate for modern historians of Islam. One of the well-known marriages hugely criticised is that of Khalid ibn al-Walid with the widow of Malik ibn Nuwayrah. He is criticised for having killed ibn Nuwayrah to marry his wife which, Islamically speaking, would be an un-Islamic act. Historical data suggest that this was far from the truth, but, unfortunately, we live in times where scandal is held higher than plain truth.

Colonial West and Polygamy

Western Christendom remains to this day behind many norms of the modern Western world. Despite the population of the modern West steadily turning away from faith and giving up any religious belief systems, certain Christian phenomena still dictate its social dynamics. Festivity remains rooted in Christian concepts of Christmas, Easter, Harvest and Thanksgiving etc.

The West’s strict aversion towards polygamy can also be traced back to the Western Christendom while arguments given against it are those given in favour of a free society where no form of legal contract is required for a man and woman to cohabit. Western legal systems, inspired by Christian ideals, have seen polygamy as a crime on the grounds that “it fosters inequity, confuses children, and jeopardizes marital consent”. (John Witte Jr, The Western Case for Monogamy over Polygamy, Cambridge University Press, NY and Cambridge, 2015)

The fact that the same does not apply to cohabiting, where couples live together without any marital contract, having children out of wedlock, and the confusion of the latter over parental ownership is a clear indication that the West has got it all wrong in understanding the concept of Islamic polygamy.

John Witte Jr, in his detailed work The Western Case for Monogamy over Polygamy, highlights how the balance in the West is tilting more towards polygamy. He believes that “polygamy will come to dominate public deliberation and litigation in many Western countries in the near future”. (Ibid)

Gallup survey shows that in America alone, the tide seems to be turning where the moral acceptability of polygamy is witnessing a constant uptick. From 7% in 2004, the trajectory of moral acceptability has gone up to 20% in 2020, and is still creeping upwards.

The Case of Mufti Sadiq Sahib

Speaking of America, we take the case of Mufti Muhammad Sadiq Sahib, the first Muslim missionary to arrive in modern America in 1920.

As soon as Mufti Sadiq Sahib set foot on American soil, he was detained by immigration authorities on account of being a Muslim who would preach polygamy. He had to assure the authorities that polygamy was an option in Islam and not an obligation. He also wrote to newspapers to have his voice heard, one of which was the Evening Public Ledger:

“I am detained because I must show my authority as an Ahmadi preacher […] and because I come from a country and nation which allows polygamy. I am going to appeal. I am not a polygamist myself, having only one wife, who is in India with our four children […]” (Evening Public Ledger, Philadelphia, 20 February 1920)

This one wife of his was Imam Bibi whom he had married in India, as we understand from his various biographical accounts. (Zikr-i-Habib [an autobiographical account], Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, p. 173)

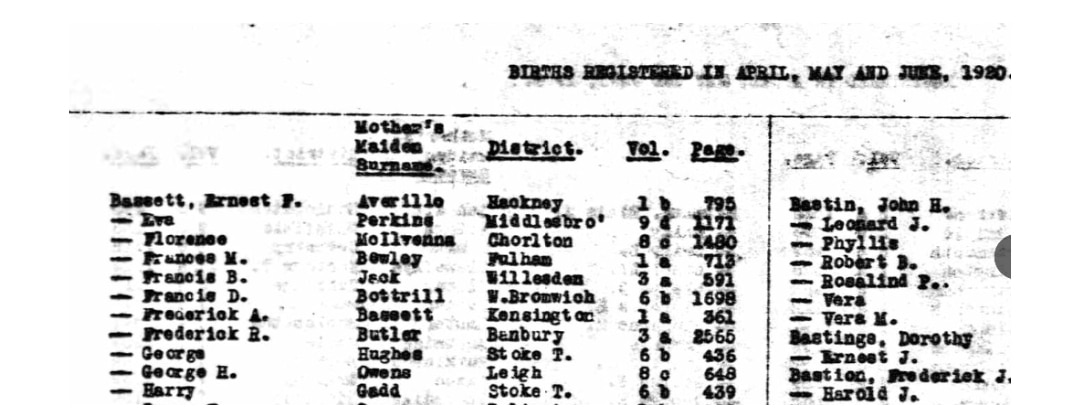

The Ipswich Star, on 19 November 2023, has published an account by some newfound grandchildren of Mufti Sadiq with evidence that he married their grandmother, Ethel Maud Bassett, during his stay in England (1917 – January 1920). He also fathered her child, Frederick A Bassett, who was born in May 1920 – about five months after his departure from England to America.

The family, in their quest for their grandfather, have collected a number of documents to piece the jigsaw together. Many pieces, however, remain missing. Also in their possession are a number of letters written by Mufti Sadiq to his son Frederick – whom he addresses with the Muslim name Farid – where he fondly advises his long-lost son about good and bad, dos and don’ts of life.

In February 1947, Mufti Sadiq sent his “dear son Farid” a book that he had recently authored, titled “Lataif-i-Sadiq” (anecdotes of Sadiq). He also advises him that being in the Urdu language, he might not be able to read it. However, we know from other father-to-son letters that Mufti Sadiq advised his son to visit the Fazl Mosque in London and meet with the missionary Mushtaq Bajwa Sahib; we know from the letters that he did. So, Frederick could have had the book read if he chose to do so.

Frederick might not have known Urdu, but the author can confirm that this autobiographical account of Mufti Sadiq carries no mention of Frederick’s mother, Ethel.

This, combined with his statement that he only had one wife who was in India, suggests that the marriage between Ethel Bassett and Mufti Sadiq might have only been a very short episode.

Since some demand legal registry documents to prove marriage, it must be clarified that the only requirement of marriage in Islam is nikah – a public announcement before two witnesses that a man and woman have agreed to live together as husband and wife, under a matrimonial contract.

The same applies to divorce in both Islamic modes – talaq where a husband divorces the wife, or khula’ where a wife divorces the husband. It has to be publicly announced that the two are breaking the wedlock and will no longer be living together as man and wife.

There are, however, legal requirements that ensue a divorce where the husband is required the dowry in the case of talaq or that the woman cannot be divorced if pregnant at the time.

Frederick was born on 20 May 1920 which is exactly five months after Mufti Sadiq’s departure for America (January 1920). This means that Ethel must have been four-months-pregnant at the time of his departure.

Mufti Sadiq’s statement to the authorities and open letters to the American press suggest that he was not in nikah with Ethel, nor was he aware that she was pregnant with his child. But since the pregnancy must have happened while they were Islamically in nikah, it means that the divorce must have happened in the preceding four months, but right at the very onset of the pregnancy when both were unaware that she had conceived.

Another hypothesis suggests that if they were aware of the pregnancy, Ethel must have exercised her Islamic right to divorce by way of khula’.

Whatever the case, Mufti Sadiq’s statement makes it clear that he was only married to Imam Bibi at the time of his arrival at the American port. Had he arrived in America with the intention to marry American women, he had no reason to plainly declare his marriage in India, especially at a time when there were no means for facts to be verified by American authorities.

The only assurance that the American authorities required was that Mufti Sadiq would not preach or practice polygamy while in America. Whether he was polygamous already or not was not the question.

Moreover, had he intended to be polygamous in America, marriage to Ethel would have been a perfect precedent to present to American immigration control – more so with a child on the way.

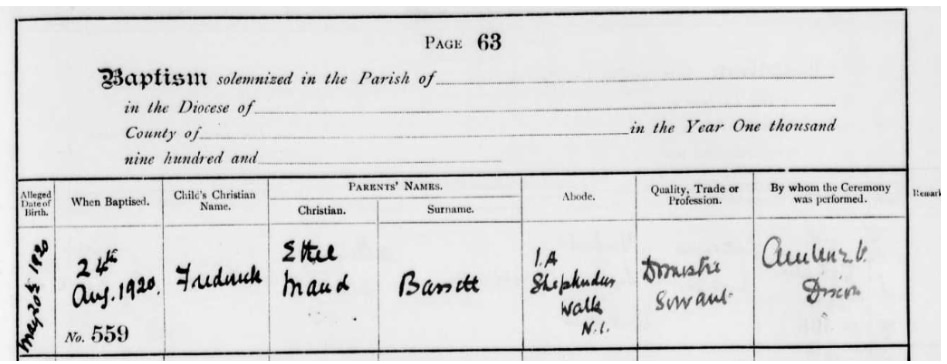

Also suggesting that the marriage with Ethel had ended in divorce is the birth registration of Frederick where he is listed with the surname “Bassett”. In his baptism certificate, in the column asking for parents’ name, the only name given is “Ethel Maud Bassett”.

Had the marriage been still on, there was no reason for Ethel not to give Mufti Sadiq’s name as the father of the child. Even in the case of a divorce, there was no apparent reason to conceal the father’s name.

In light of what we know so far, Ethel abandoned Frederick by sending him to an orphanage-style care system of Barnardo’s, which is evident from the documents in possession of Frederick’s children and published by Ipswich Star.

But this happened later on. From the time of his birth, Frederick was deprived of his true identity by concealing his father’s name. He was baptised, despite the fact that Ethel Bassett had converted to Islam, confirmed by Mufti Sadiq’s report published in the Al Fazl Qadian, on 10 June 1919, where it said:

“Two respectable ladies, by the names of Ms Bassett and Mrs Sals have accepted Islam at the hand of Hazrat Mufti Muhammad Sadiq Sahib, missionary of Islam. Their Muslim names are Majidan and Fatimah. Praise be to Allah.”

The Review of Religions, in its issue of May, June, July 1919 published the same in English:

“Five English Ladies and Gentlemen joined the fold of Islam in the month of May. Their names are Miss E Maud Besset [sic.], Mrs Alice Sals, Mrs Gurr, Miss Bysouth, and Mr Scott.

“They have been respectively given the Muslim names of Majidan, Alia, Amina, Mariam and Abraham, and their applications for initiation into the Ahmadia Movement have been forwarded to His Hazrat Khalifat-ul-Masih.”

The above report, published in the Al Fazl of 10 June 1919, is dated 7 May 1919. We can safely assume that Ethel converted to Islam sometime in early May. The marriage must have happened in the Summer of 1919 before she conceived Frederick around September (counting back from his birth in May 1920).

It is around the same time that marriage seems to have fallen apart. No one can say for sure, but the little amount of evidence that we have supports the assumption that Ethel abandoned Islam and her husband who was also the father of her unborn child. The evidence the author uses here is the baptism certificate of Frederick A Bassett (baptism dated 24 August 1920).

Had Ethel remained a Muslim, Baptism would have not been anywhere in the equation. The same applies to the name Frederick which is very much a Christian name and not a Muslim one.

That Mufti Sadiq later made effort to establish contact with his son Frederick, fondly addressing him as Farid, shows that he did not abandon his child. The mother of the child seems to have kept him from making any contact with the father.

While there is no registry document to prove the legal marriage of Mufti Sadiq and Ethel Maud Bassett, there is sufficient evidence to believe that Islamic marriage did take place. The letters written to Frederick by Mufti Sadiq advise him to visit the Fazl Mosque in Southfields, London, and stay in contact with the missionary there. Letters suggested that he visited the mosque and remained in touch with the mosque before losing contact.

Had there been no nikah and the child was born out of wedlock, Mufti Sadiq would never have made any effort to, firstly, find this child of his and, secondly, to get him in touch with the mosque where everyone knew Mufti Sadiq as their pioneering missionary and held him in very high esteem.

The story of Mufti Sadiq and his son Frederick is a sad one. It hurts to see that ever since the publication of the article in Ipswich Star, some Social Media users have been using foul language about this child, his mother and his father.

They lived in a time when life was much different than as know it today. Ethel was not a bad lady. Mufti Sadiq’s report published in the aforementioned issue of The Review of Religions mentions her as someone who was helping Mufti Sadiq in his missionary activity. He writes:

“I am still suffering from granular eyelids which has rendered me unable to do any reading or writing work. Some English Muslim friends (such as Mrs Jameela Shah, Mrs Abasi and Miss Besset [sic.] and Abdul Rahim Alabi Smith, a young Nigerian Ahmadi, have been of great help in disposing of my correspondence. May God be their reward.” (The Review of Religions, May, June, July 1919, p. 229)

We can only wonder what might have led Ethel (or Majidan) away from Islam. Those were very challenging times for Muslims living in the West. In the book that Mufti Sadiq sent to his son in London, he narrates a very interesting anecdote:

“A tough situation arose for Mufti Sahib in America, but God saved him miraculously. Mufti Saheb had been preaching Islam to a young American girl who was almost ready to accept the message. Her mother was a bigoted and stubborn woman who tried to stop her daughter from converting to Islam through every possible effort. Having failed, she filed a false lawsuit against Mufti Sahib, accusing him of being part of a dangerous mission where girls are abducted and then married off to Muslim men; and that the same was happening to her daughter.

“The lawsuit was horrific but was dismissed in its very early stages, hence relieving Mufti Sahib of a burdensome worry.” (Lataif-i Sadiq (being the autobiography of Mufti Sadiq Sahib), ed. Sheikh Muhammad Ismael Panipati, published by Tajir Kutab Qadian, 1946)

Such were the times when being Muslim was a thorn in the West’s eye. The resilience of Muslim missionaries becomes even more commendable in such circumstances.

Their families shared the burden of their sacrifice and must have received their share in the rewards from God Almighty.

Note from author: The above is based on the data and information so far available. As more comes to light, further reseach will be carried out and presented.