Imran Ahsan Karim-Mirza, Australia

Age of new weapons

The 20th century was a paradox of progress and peril. While it ushered in unprecedented technological and scientific advancements, it also witnessed the birth of weapons so devastating that they reshaped the course of history and redefined the boundaries of human suffering. We exist beneath the looming shadow of destructive forces, wielded and orchestrated by the world’s dominant powers.

World War I introduced industrialised warfare, where machine guns, tanks, and poison gas turned battlefields into mechanised slaughterhouses. The use of chemical weapons like chlorine and mustard gas inflicted horrific injuries and psychological trauma, marking a grim milestone in the evolution of combat.

World War II escalated the horror. Strategic bombing campaigns razed cities, and the Holocaust mechanised genocide.

But the most chilling legacy was the advent of nuclear weapons. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 killed over 200,000 people, many instantly, others slowly through radiation sickness. These events not only ended the war but inaugurated the nuclear age – a period defined by the existential threat of global annihilation.

The Cold War saw the proliferation of nuclear arsenals, with superpowers locked in a precarious balance of terror. The doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) ensured that any conflict could escalate into a planetary catastrophe.

Meanwhile, proxy wars in Korea, Vietnam, and Afghanistan introduced new forms of guerrilla warfare and chemical defoliants like Agent Orange, leaving long-lasting ecological and human scars.

Beyond the battlefield, the century saw the rise of biological and chemical weapons – silent, invisible killers capable of mass destruction.

We stand at the threshold of a new era – one brimming with extraordinary possibilities yet shadowed by the spectre of unprecedented destructive power.

Emerging genetic technologies, such as CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats), hold the potential to reshape life itself. CRISPR is the guide that identifies the target DNA sequence and Cas9 is the enzyme that cuts the DNA at the targeted location.

With its power comes peril. We may unwittingly unleash forces beyond our control – creations born not of nature, but of ambition – monsters cloaked in the promise of progress.

This is not a warning born of fear, but of foresight. We must be vigilant and forewarn of the coming decades, where the line between innovation and devastation grows ever thinner, and where humanity must tread with wisdom, lest it awaken what it cannot contain. The Holy Quran states:

“‘And assuredly I will lead them astray and assuredly I will excite in them vain desires, and assuredly I will incite them and they will cut the ears of cattle; and assuredly I will incite them and they will alter Allah’s creation.’ And he who takes Satan for a friend beside Allah has certainly suffered a manifest loss.” (Surah an-Nisa’, Ch.4: V.120)

To better grasp the magnitude of potential risks, let us explore a few illustrative examples that shed light on the darker possibilities these technologies may unlock.

Genetic frontiers and the risk of unintended consequences

The woolly mammoth: Engineering the Ice Age

The woolly mammoth, extinct for over 4,000 years, is at the centre of a bold scientific mission led by Colossal Biosciences, a biotechnology company based in Dallas.

Rather than recreating a mammoth in its pure form, the goal is to engineer a cold-adapted “mammophant” – an Asian elephant genetically modified to express mammoth traits such as thick fur, subcutaneous fat, and cold tolerance.

Recent breakthroughs include the creation of “woolly mice”, genetically engineered rodents that exhibit mammoth-like traits.

These mice serve as a proof-of-concept for genome editing techniques that may later be applied to elephants. Scientists have identified key genes from mammoth DNA – retrieved from permafrost-preserved specimens – and successfully edited them into mouse genomes to produce longer, golden-coloured fur and cold-adapted fat metabolism.

Researchers hope that reintroducing mammoth-like elephants to Arctic tundra could help restore grasslands and slow permafrost thaw, thereby mitigating climate change.

However, critics caution that the ecological consequences of such reintroductions are unpredictable and potentially disruptive.

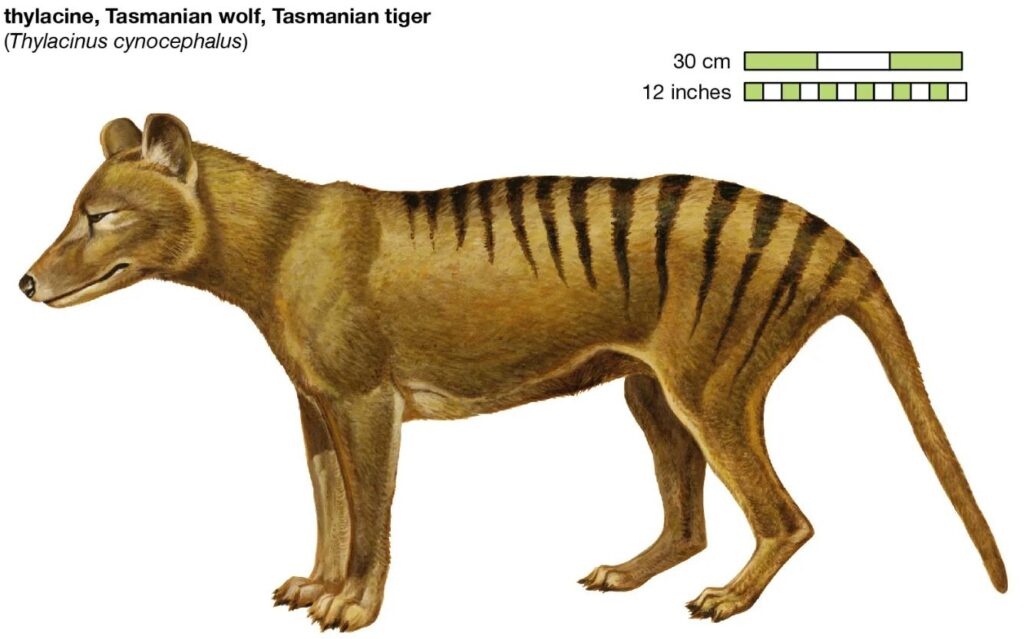

The Tasmanian Tiger: Reviving a lost predator

The thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, was declared extinct in 1936. Now, a partnership between Colossal Biosciences and the University of Melbourne’s TIGRR Lab, led by Professor Andrew Pask, is working to bring it back.

Their approach involves sequencing the thylacine genome and editing the DNA of its closest living relative – the fat-tailed dunnart, a small carnivorous marsupial.

In a major milestone, the team has reconstructed a 99.9% complete thylacine genome, the most accurate ancient genome to date. They also extracted long RNA molecules from a 110-year-old preserved thylacine head, enabling insights into gene expression and tissue function. Over 300 genetic edits have been made to dunnart cells, transforming them into thylacine-like cells – the most edited animal cells ever recorded.

The team is also developing marsupial artificial reproductive technologies, including inducing ovulation and culturing embryos in artificial wombs. These innovations not only support the thylacine project but could aid conservation efforts for endangered marsupials like the Tasmanian devil.

CRISPR and the genesis of tomorrow: Between resurrection and reinvention

In the unfolding story of modern science, few innovations have stirred as much awe and apprehension as CRISPR-Cas9.

The 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Dr. Emmanuelle Charpentier and Dr. Jennifer A. Doudna for their pioneering work in developing a method to precisely and efficiently edit DNA.

This revolutionary gene-editing tool, often likened to molecular scissors, allows scientists to cut, modify, and rewrite the genetic code with unprecedented precision. It is a technology that holds the promise of healing, of restoration – and of reinvention.

At the heart of this promise lies a profound ambition: to revive the extinct and to design the living. Beyond the realm of resurrection lies a more controversial frontier: the creation of designer animals.

With CRISPR, it is now possible to engineer organisms with tailored traits – whether for agriculture, companionship, or research. Imagine livestock bred for disease resistance and enhanced productivity. Yet with such extraordinary power comes a cascade of ethical dilemmas that cannot be ignored.

As we begin to shape life at the genetic level, we must ask: are we prioritising human convenience over the well-being of sentient creatures? The welfare of animals – engineered for traits we deem useful or desirable – may be compromised in ways we do not yet fully understand.

There lies another possibility – one both fascinating and deeply unsettling. If the preserved DNA of extinct animals proves too fragmented or degraded, scientists may turn to a broader strategy: analysing multiple specimens to reconstruct a complete genome.

Much like the cloning of Dolly the Sheep, this reconstructed DNA could then be used to create a living organism, gestated not in a natural womb, but in an artificial one, crafted by emerging biotechnologies.

The final word of caution

I find it deeply perplexing that many proponents of Darwinian evolution – who often engage passionately in debates with religious thinkers – remain conspicuously silent on the ethical implications of technologies like CRISPR.

These are tools that, in essence, shortcut a natural process that unfolded over nearly four billion years, shaping the intricate tapestry of life through gradual mutation, selection, and adaptation.

The emergence of traits, the differentiation of species, and the vast diversity of life were not instantaneous – they were the result of countless generations of evolutionary refinement.

Yet today, we stand on the brink of bypassing that entire journey, reconstructing life in laboratories and artificial wombs, guided not by nature, but by human ambition.

The awarding of the Nobel Prize for CRISPR is a celebration of human ingenuity – one that echoes the scientific triumphs of the early 20th century, when minds like Albert Einstein and his contemporaries reshaped our understanding of the universe.

Yet, as history reminds us, such breakthroughs are often double-edged. The same physics that unlocked the mysteries of space and time also laid the foundation for nuclear weapons – tools of immense destruction born from the pursuit of knowledge.

Such technologies, once unleashed, may not stop at restoration. They may evolve – driven not by caution, but by ambition and human greed for power. And as history has shown, when human lust for power and desire take hold of transformative tools, the consequences can be catastrophic.

Just as nuclear technology, discovered 85 years ago, was swiftly weaponised and turned into instruments of mass destruction, so too could genetic engineering be twisted into darker purposes.

The Holy Quran warns us of this very tendency: that unchecked desire for dominance leads humans to align with forces of corruption – associating with Satan, who seeks power through deception and destruction (Surah al-Qasas, Ch.28: V.84).

The monsters born of such ambition may not resemble the towering beasts of Jurassic Park – not mammoths or tyrannosaurs – but could be far more insidious.

They may be microscopic, engineered bacteria or viruses designed not to restore life, but to target and eliminate it – infecting populations, manipulating genetics, or even weaponising biology against specific ethnicities or regions.

This is not a prophecy of doom, but a call for vigilance. For in our pursuit of mastery over life, we must not lose sight of the moral compass that guides it.

CRISPR’s ability to reshape life is both exhilarating and sobering. Reviving extinct species may help heal ecological wounds, but creating designer animals could open a Pandora’s box of unintended consequences.

Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmadrh, Khalifatul Masih IV, warned us in his book, Revelation Rationality Knowledge and Truth. He had said:

“The possibility of changing the nature of God’s creation was not an idea that people of earlier times could have entertained. Clearly the verse [Surah an-Nisa’, Ch.4: V.120] is speaking of possibilities that had not yet dawned on the horizon of earlier eras.”

He further stated:

“[…] the possibility of man bringing about substantial changes in God’s creation has always been beyond the reach of human imagination, prior to the most recent times. The addition of genetic engineering as a new branch of scientific study is only a decade or two old.

“Yet this branch of science is moving rapidly to the stage against which a clear warning had been delivered by the Quran fourteen hundred years ago. Man has already started interfering with the plan of creation and to some measure has succeeded in altering the forms of life at the level of bacteria, insects etc. A few steps further and it may spell disaster.” (Revelation Rationality Knowledge and Truth, Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmadrh, p. 628)

The Holy Quran speaks of possibilities too:

“From bringing in your place others like you, and [from] developing you into a form which [at present] you know not. And you have certainly known the first creation. Why, then, do you not reflect?” (Surah al-Waqi’ah, Ch.56: V.62-63)

History has shown us that humanity’s pursuit of power, when untethered from wisdom, can turn innovation into devastation.

Just as the discovery of nuclear technology 85 years ago led not only to scientific breakthroughs but also to the creation of weapons of unimaginable destruction, so too does CRISPR and other emerging genetic technologies stand at a similar crossroads.

This time, however, the consequences could be even more profound. The ability to rewrite the genetic code of life itself – whether to resurrect extinct species or engineer new ones – places in our hands a power both magnificent and perilous.

If driven by greed or ambition, rather than guided by ethics and foresight, these tools could unleash biological forces that we neither anticipate nor control.

“Dost thou not see that Allah created the heavens and the earth in accordance with the requirements of wisdom? If He please, He can do away with you, and bring a new creation.” (Surah Ibrahim, Ch.14: V.20)