Asif M Basit, Ahmadiyya Archive and Research Centre

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was not just a novelist but had a very spiritual side too. He also was an active advocate for human rights and saw beyond divides of colour, creed and faith. He found a platform for this noble cause by attending meetings and signing petitions at London’s first mosque: The Fazl Mosque.

This is the lesser-known story of how literary greats like Arthur Conan Doyle and many more actually stood behind the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in fighting for Muslim rights in a civilised and cordial manner.

When we talk of fictional characters coming to life, Sherlock Holmes is one of the first names that comes to mind. Created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in the latter part of the 19th century, Sherlock Holmes lives on – and will continue to, it seems.

Like the genie from Aladdin’s lamp, Sherlock Holmes emerged from Arthur Conan Doyle’s pen in a story titled A Study in Scarlet. But unlike the genie from the lamp, Sherlock Holmes never went back into the pen and turned into a larger-than-life character – and way larger than any fictional character ever.

This unprecedented tide of popularity washed the English-speaking world like never before and left everyone surprised. The author himself had not seen this coming and, it seems, was left more shocked than merely amazed.

Literary critiques have found Sherlock Holmes’ character to be an imaginary embodiment of its creator. While working as a clerk for a surgeon, Joseph Bell, at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, Doyle was deeply moved by the deep conclusions that Bell would draw from minute details that he observed in bodies – both alive and dead, but more so in the latter.

Those who have read Sherlock Holmes stories (or fashionably watched these days) would know that what gives Holmes his special place in detective fiction is his remarkable ability of applying deductive logic – so remarkable that it rubs shoulders with the fantastic periphery of psychic phenomenon. Joseph Bell, despite being the inspiration behind the character, insisted that Sherlock Holmes was none other than Arthur Conan Doyle himself.

Reading through the biography and autobiographical accounts of Doyle, one cannot miss the spiritual side of his personality. He was a deeply spiritual person, a trait that his biographers traced back to when his eldest son died, but Doyle always insisted that he had always been so – he placed the mark around 1887.

It isn’t surprising that the character of Sherlock Holmes sprang to life at a time when Doyle had discovered a spiritual bent in himself. This, added to his adoration for the art of forensic deduction, is what Sherlock Holmes is all about.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was, thus, an embodiment of Sherlock Holmes – a character he had developed and nurtured. Some biographers also suggest that Doyle felt that Sherlock Holmes had grown into a much bigger personality – one that overshadowed, outshone, and towered over its own creator. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s deeply spiritual soul, in search of peace and tranquillity, would take him many places – just as always happened with Sherlock Holmes.

“Sherlock Holmes” visits Fazl Mosque

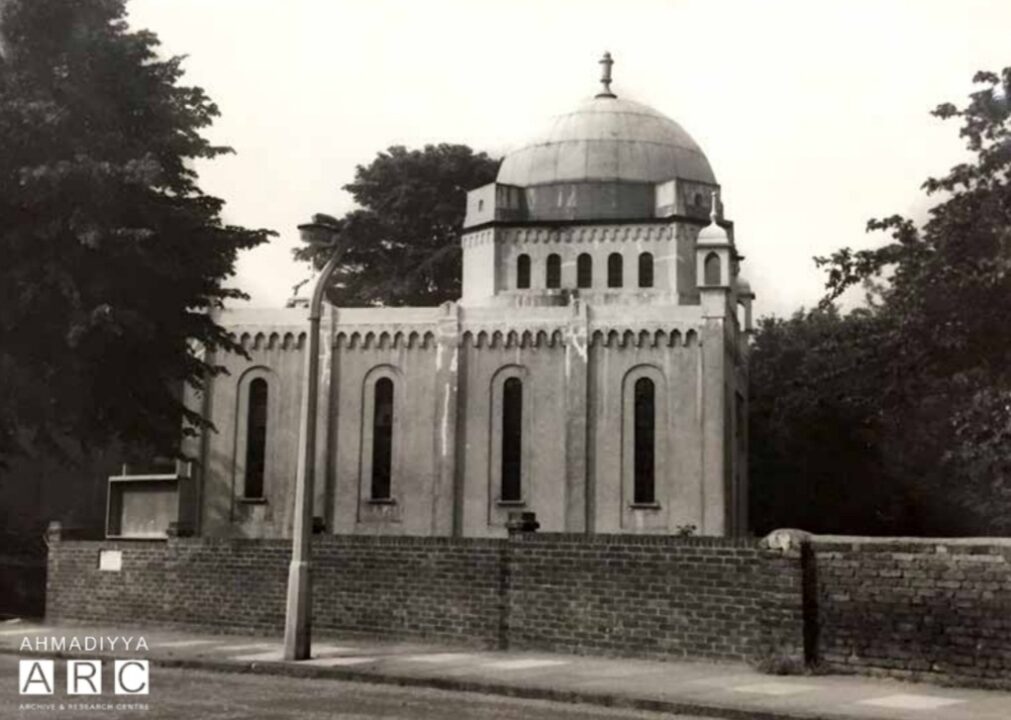

In the 1920s, this “Sherlock Holmes” is found frequenting the mosque in Southfields in the South West of London – the Fazl Mosque, and more commonly known as the London Mosque. How he had come in contact with the mosque is something I am still looking into and hoping to find very soon. But he is seen on multiple occasions attending meetings at the mosque and signing petitions that the imam of the London Mosque would send to the prime minister of Great Britain and to other influential figures at Whitehall.

Those were the years when this was the only purpose-built mosque in London and functioned as a symbol of Muslim representation. Founded by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community of Qadian, the imam of the London Mosque was seen as the most vocal mouthpiece of Indian-Muslims, and that too based in the heart of the British Empire.

To keep this piece short and concise, (as I am sure Sherlock Holmes would like), I cite two such instances where Sir Arthur Conan Doyle spoke up for the rights of Muslims in India.

The British press, as well as the mainstream press in India, reported on 4 August 1927:

“Rangila Rasul

“Five Hundred Signatories to Petition

“Maulvi Abdur Rahim Dard, M. A., Imam of the London Mosque, cables […] that 500 persons have so far signed the proposed petition to the Secretary of State for India, including Sir A Conan-Doyle, Sir J Hope Simpson, Sir Stanford London, Sir Robert Hamilton and other notables.” (Civil and Military Gazette, 4 August, 1927)

Just to remind our readers, the Rangila Rasul controversy was a heartwrenching episode of colonial India where Rangila Rasul was a book produced by anti-Islam circles and slandered the character of the Holy Prophetsa of Islam.

While riots broke out in protest across the country and the Hindu-Muslim communal conflicts saw a very ugly height, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community presented the case in the most peaceful and powerful manner before the British Government – the most appropriate forum for such cases.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle must have admired the way the meeting was conducted at the mosque and a petition signed, contrary to the violent reaction that other Muslims had shown.

Two years before this, in 1925, two Ahmadis had been stoned to death in Afghanistan at the behest of the Amir of Kabul. The London Mosque had raised the matter through peaceful protests held in the form of meetings and through petitions being sent to international bodies. It was seen, as the press reported heavily and rightly, as a murder of not only two Ahmadis but a butchery of fundamental human rights: “The recent stoning to death in Kabul of two more Ahmadis […] has aroused much sympathy in the civilised world and the protests have been by no means confined to Muslims.

“In London a largely attended meeting was held at Harrow and the following resolution was passed:

“‘We, the undersigned, affirm the principle that freedom of conscience is the birthright of humanity, and desire to record our emphatic disapproval and condemnation of the reported conduct of the Afghan Government in stoning to death two more Ahmadis on grounds of differences of belief […].’” (Civil and Military Gazette, 8 April, 1925)

The news story goes on to list the prominent signatories, among whom Sir Arthur Conan Doyle is one of the topmost.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was not the only one to visit the mosque and be a part of its peacebuilding mission. Novelists like Roald Dahl and HG Wells were among the many members of the English literati that maintained close ties with the Fazl Mosque in London; but theirs are stories we put off for another time.

The London Mosque remained a centre of Muslim representation and human rights, as well as being a flagbearer of interfaith harmony, right from the time of its inception. Where Muslims like MA Jinnah, Sir Muhammad Iqbal, Sir Fazli Hussain, and Sir Sheikh Abdul Qadir would turn to this mosque to touch base, others in search of a soul and a voice for humanity would also find solace in it. This mosque has just turned 100 years old (cornerstone laid in October 1924).

It carries with it the legacy of being London’s first mosque and a beacon of peace and harmony for the global society.