Asif M Basit, Ahmadiyya Archive and Research Centre

Part I: What’s in the book…

The year 1897 is of great historical importance in the history of modern Islam. It was the year when the degeneration of the Ottoman Caliphate – a symbol of Muslim political grandeur – started to set in. The only memento of the bygone Muslim glory had met its end game at the hands of the Young Turks and the so-called Caliph was turned into a mere symbolic figurehead.

This degeneration of the Ottoman Empire was preceded by the fall of the Mughal Empire – another Muslim power. Ever since, Muslims had looked up to Turkey as a representative of the once-upon-a-time Islamic splendour that they had only heard of in tales and bedtime stories.

The scope of this article is not the details of the fall of the Mughal Empire. Thus, without attempting to agree or disagree with historians who locate the marker at the end of Aurangzeb’s reign, or try and trace it in the Durrani and Marattha attacks, we place it at 1857 – the fall of the Red Fort of Bahadur Shah Zafar.

Thus, we have before us, for this study, a period of forty years that lay between the crumbling of two Muslim empires – the Mughal and the Ottoman; and, hence, we are looking at two regions of dense Muslim population – India and Turkey.

Alongside its symbolic value as an Islamic empire and the home of the Islamic Caliphate, the Ottoman Empire had remained the hotbed of civil wars and infighting. Not only was the Armenian genocide an ugly blemish on its record sheet, but the bloody battles fought against its coreligionists for the conquest of the holy shrines of Islam in Mecca and Medina – often through sacrilegious military operations – had left deep scars on the Muslim collective psyche.

Such episodes of infighting and persecution had cemented the impression that Ottoman lands were not favourable for religious freedom.

On the other hand was India, under the British Raj, where religious freedom was showcased as the hallmark of the British Empire. The Queen’s Proclamation of 1858 had granted native subjects the freedom to proclaim and profess a faith of their choice and practice it in whatever way they liked. Hindu-Muslim conflicts did muddy the socio-religious waters of British India, but that was a communal matter and not state-sponsored.

Whether the British Raj was a beneficiary of these communal tensions or not is, again, not within the scope of this brief study. We know as an historical fact that British rule had granted religious freedom to its subjects in India.

Another historical fact that cannot be denied is that the British Empire was home to 98 million Muslims – almost double its Christian population of 54 million.

It was this religious freedom that had allowed reform movements to emerge and flourish in both Hindu and Muslim sections of natives in British India. Where Hindus saw the Brahmu Samaj, Sanatana Dharam and the Arya Samaj reform movements take birth and progress, Indian Muslims witnessed the emergence of the likes of the Aligarh, Barelvi, Deobandi, Faraizi, Ahrar, and the Ahmadiyya movements of Islamic reform.

All these movements acknowledged the favourable atmosphere provided by the British Raj for their functioning and coexistence, often expressing their gratitude wholeheartedly.

The Aligarh Muslim College and the Madrsa Dar al-Uloom Deoband owed their very existence to British patronage and funding. Ahmad Raza Khan Barelvi vehemently issued fatwas in favour of the British Raj and against any resistance towards it.

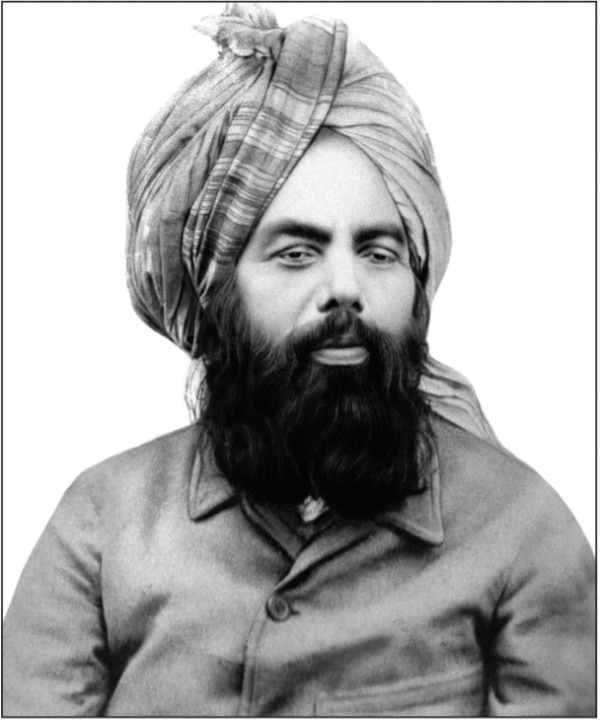

The founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement would refer to Islamic principles of remaining loyal to the ruler and the law of land, showing gratitude to both through words and action. Believing that Allah alone was the Supreme Sovereign (Malik al-Mulk), and that worldly rulers were entrusted by Allah, Hazrat Ahmadas insisted on and practised devotion towards the ruler of the land – the British in the case of India of his days.

How justified his devotional attachment to the British Crown was, we leave that for some other time. Here we address a question recently raised by the critics of the Ahmadiyya Community.

The Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria

As the entire British Empire celebrated the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria in the Summer of 1897, India was no exception; nor were Indian Muslims. The Civil and Military Gazette, Lahore reported on the “Muhammadan” frenzy:

“The Muhammadan deputation for presenting an address of congratulation to Her Most Gracious Majesty on the completion of the 60th year of her reign left Lahore to-day (Friday) for Simla to present the same to the Viceroy. The drum was also beaten through the city, Anarkali Bazaar and Mian Mir summoning all Muhammadans to pray for Her Majesty and all the Royal Family in the Badshahi (King’s) Mosque and all mosques in the localities. It was further enjoined that prayers were again to be offered up on Sunday, and that on that day a feast of polao and zarda be given to the poor at the Badshahi (King’s) mosque.”(C&M Gazette, Lahore, 19 June 1897 (italics as in original and not by author)

This address, “beautifully illuminated” and placed in a “handsome silver case”, was ready by 14 June, as reported by the Civil and Military Gazette the next day. (Ibid., 15 June 1897)

The “Muhammadans of the Punjab”, on 27 February 1897, assembled at the “house of Nawab Fateh Ali Khan, Qazilbash”, to think of ways of celebrating the Queen’s jubilee. The draft of the address to be presented “contained nothing except congratulations to Her Majesty and thanksgivings to God for the happy occasion”. (Ibid., 2 March 1897)

The Muslim influential men from Punjab to be part of this delegation were unanimously agreed to be Sir Muhammad Hayat Khan CSI, Malik Umar Hayat Khan of Shahpur, and Nawab Zulfiqar Ali Khan of Malerkotla. This delegation was to be part of the main delegation of Indian Muslims to present the address to the Viceroy in Simla. (Ibid.)

This assembly of Muslim leaders and the Muslim public considered ways to give permanence to this celebration, and it was resolved that a student scholarship should serve the purpose well. The address, these Punjabi Muslims wholeheartedly agreed, should contain “prayers to God for the welfare of Her Majesty”. (Ibid.)

Newspapers from the time abundantly reported the jubilant fever that had taken the entire Indian Subcontinent, the crown jewel of the British Empire, in its grip as Muslims; along with natives of other faiths, geared up to celebrate the jubilee of the Queen Empress.

The celebrations, held in India from 21 to 23 June, received even heavier coverage all across the Empire. The press reported on how processions of Muhammadans had marched across their towns and cities, stating that it was “really a gala day for Muhammadans”.(Ibid., 23 June 1897)

Amritsar alone saw “20,000 Muhammadans” assemble for “a thanks-giving service on the auspicious occasion of Her Majesty’s Diamond Jubilee”. (Ibid.)

The Muslim public and their leaders in all towns and cities passed resolutions stating:

“In the morning prayers be offered to the Almighty God for Her Majesty and her Royal Family”.(Ibid., 7 May 1897)

Almost all meetings to commemorate the occasion heard Muslim leaders sing praises of the British Crown and “the various blessings Muhammadans were enjoying under Her Majesty’s most benevolent reign”.(Ibid., 9 April 1897)

Jubilee celebrations in Qadian

In line with the Islamic way of thanksgiving – as almost unanimously agreed upon by the Muslim population of India – the Ahmadiyya Community celebrated the Diamond Jubilee from 20 to 22 June 1897 in Qadian; with the exception of band music and the “gala” of singing and dancing, as practised by some Muslim communities of other cities.

The report of the events that took place in Qadian was produced by none else but by Hazrat Ahmadas himself, in a booklet named “Jalsa-e-Ahbab” (a meeting of friends).(Jalsa-i-Ahbab, Ruhani Khazain, Vol. 12)

The events reported are as humble as the booklet itself. The celebrations revolved around joining “in prayer and offering gratitude to Allah the Almighty” and the needy and deserving being “provided food” (Ibid., p. 295)

The theme of the thanksgiving remained around the religious freedom provided by the British Crown to its Indian subjects.

A major exception

From the abyss of information about the Indian-Muslim celebration of the jubilee, one finds in abundance reports on fanfare as well as displays of pomp, power and joy. The Qadian celebrations appear to be the only one where the Queen was invited to renounce Christianity and embrace Islam:

“For this event, a book on gratitude was compiled for the Empress of India and printed, named Tohfa-i-Qaisariya [Gift to the Empress]. Several copies were printed in decorative binding, one of which was sent to the Empress of India through the Deputy Commissioner, another to the Viceroy” (Ibid.)

A passage from the aforementioned book, sent to Queen Victoria, reads as follows:

“Almighty God! As Thy Wisdom and Providence has been pleased to put us under the rule of our blessed Empress, enabling us to lead lives of peace and prosperity, we pray to Thee that our ruler may in return be saved from all evils and dangers as Thine is the kingdom, glory and power. Believing in Thy unlimited powers we earnestly ask Thee, All-Powerful Lord, to grant us one more prayer that our benefactress the Empress, before leaving this world, may probe her way out of the darkness of man-worship with the light of la-ilaha illallah Muhammadur Rasulullah. [There is no God but Allah and Muhammad is His Prophet]. Do Almighty God as we desire, and grant us this humble prayer of ours as Thy will alone governs all minds. Amen!”(A Gift for the Queen [Tohfa-i-Qaisariya], Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas, Islam International Publications, Surrey, 2018)

Proposal for an interfaith conference

Further down the line, Hazrat Ahmadas makes a suggestion for the Queen to arrange an interfaith conference in London, the capital of the Empire, where all faiths could present their beliefs before each other and the British public.

He explained his intention behind the proposal:

“[…] It would be necessary that every participant present their faith’s excellence and not malign others. If such a conference takes place, it will be a legendary spiritual event from our Honoured Queen; and England, which has been fed with Islamic matters incorrectly, will be introduced to the true face of Islam.” (Ibid.)

The defence of Islam appears to have been at the core of the celebration of the Jubilee, and not just an expression of gratitude or pledges of loyalty.

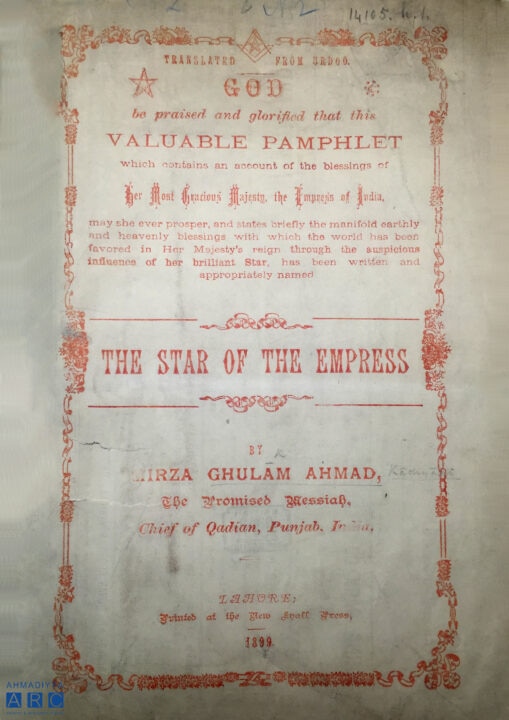

Having received no acknowledgement for the invitation to Islam or to the proposal of an interfaith conference, Hazrat Ahmadas wrote another booklet, titled Sitara-i-Qaisra (The Star of the Empress). He explained the need to write this booklet as owing to not having received a reply to his previous book, which contained an invitation to Islam and a proposal for an interfaith conference in the Empire’s capital. He went on in the booklet to reiterate the same.

The book was originally written in the Urdu language, and translated into English under the title “The Star of the Empress” to be sent to the Queen.

The very first line of the text on the title page reads: “Translated from Urdoo”.

The next line reads: “God be praised and glorified […]”

His titles appear, after his name, as “The Promised Messiah” and “Chief of Qadian, Punjab, India”

Part II: What’s on the book…

The riddle of the Freemasonry emblem

What has recently intrigued critics of the Ahmadiyya is the presence of the Freemasonry emblem (or one that resembles it) in the border of the title page, in the middle and right at the top.

This has led them to question whether Hazrat Ahmadas had any connection with the Freemasons.

To analyse the query, we take two routes to resolve the puzzle.

- Hazrat Ahmad’sas views on Freemasons

- The Printing Press in 19th Century India

Views on Freemasons

The book in question was written and published in 1899. The first mention we find of Freemasons in Hazrat Ahmad’sas recorded works is in 1901:

“Sometimes, I feel that I find out the truth behind Freemasonry, but I have never had the chance to look into it. What he [Alexander Dowie] writes about them hints at the greatness of a revelation that I received; the idea of which was that ‘Freemasons will not be appointed for his murder’.

“It could be that this revelation points to the truth behind Freemasons, like where matters cannot be resolved through law, they exert their influence. I believe that high-ranking officials and members of the nobility, even some princes, could be Freemasons […].”(Al Hakam, Qadian, 17 November 1901)

Here, Hazrat Ahmadas appears oblivious to what Freemasonry actually is and how it functions.

Records suggest that six years later, he was more aware of Freemasons and had a very strict aversion towards them. This could be due to the Freemasons being in the news, even in the vernacular press, in the time that had lapsed from 1901 to 1907. The Amir of Kabul, Habibullah Khan, had joined Freemasonry during his visit to India. This had resulted in a great deal of hue and cry among his subjects in Afghanistan, expressing resentment towards this act of their Amir, which they saw as clearly un-Islamic.

The Badr, Qadian, recorded the words of Hazrat Ahmadas on 3 March 1907:

“Upon mention of the Amir of Kabul joining Freemasonry and the resentment of his people, Hazrat Ahmadas said: ‘Their resentment is justified because any monotheist and true Muslim cannot join Freemasonry. Its origins are in Christianity and to progress to certain stages, one has to be baptised. Hence, joining it is express apostasy”.(Badr, Qadian, 3 March 1907)

Why critics of the Ahmadiyya are so easily inclined to believe that Hazrat Ahmadas, might have had connections with Freemasonry, could possibly be due to the fact that many influential Muslims from his time had become Freemasons.

We have mentioned above Habibullah Khan, the Amir of Kabul.(Henry McMahon, An Account of the Entry of H. M. Habibullah Khan Amir of Afghanistan into Freemasonry,London, Favil Press, 1936) Abd al-Qadir al-Jazairi (1808-1883), the Algerian Amir and a prominent Muslim from the Qadiriya Sufi order, was initiated at the lodge Les Pyramides of Alexandria in Egypt in 1864.(Karim Wissa, Freemasonry in Egypt 1798-1921: A study in cultural and political encounters, in Bulletin British Society for Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 16 No. 2)

Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, a beloved of many South Asian and Arab Muslims, had joined Freemasonry. In one of his letters, he confirms that “I entered the lodge on April, 7, 1876 […]”. Not only was he initiated at the lodge Star of the East, he continued to move up the ladder and became Grand Master of the same lodge.(A Albert Kudsi-Zadeh, Afghani and Freemasonry in Egypt, in Journal of the American Oriental Society, V. 92 No. 1)

Hence, with an Amir of a Muslim territory, a leader of a Muslim people and a Muslim stalwart of the resistance movement against foreign rule being on the list, it seems to make it easier for Ahmadiyya critics to jump to conclusions.

Printing Press in British-India

As mentioned above, the original Urdu book, Sitara-i-Qaisra was published in 1899. The print line at the bottom of the title page reads:

“[…] printed at Zia al-Islam Press Qadian by Hakim Fazl Din, proprietor of the press […]”(Sitara-i-Qaisriyyah, Ruhani Khazain, Vol. 15, p. 109)

The text of the book as well as the floral borders around the text of the title page show that the book was printed on a lithographic printing machine.

The translation, The Star of the Empress, the one we are concerned with here, was printed on a typographic printing press.

Typographic printing machines would involve compositors placing individual letters, punctuation marks and spaces to reproduce the elements of a manuscript.

This process was an extremely laborious one where every single page would involve hundreds of words and a number of punctuation marks, not to mention spaces that demanded an equal amount of labour and attention.

The words that fitted on the tray of a single page would be laid in the machine, inked, and then the paper would be rolled onto them with a roller. The same would be repeated for every single page as many times as the number of copies required.

Printing in India was a specialised field in the 19th century and would require a large number of workers, including trimmers, sorters, washers, sponge men, inkers, and compositors.

Since it was the compositors who arranged letters and all other characters to reproduce the text of the manuscript, they were seen as not merely labourers but as skilled workers. They were required to have good proficiency in the language as well as an eye for detail to avoid any mistakes, as the latter could result in the printer not being paid by the client.

This placed compositors at the top of the press labourers’ hierarchy. The most skilled of these would be employed, after thorough scrutiny and testing, by presses that printed government material and, hence, required an even keen eye and a greater level of care.

The other presses that took immense care were those owned by Christian missionary societies that printed evangelical material in huge bulks.

At the tail end of the chain were vernacular presses, which, before lithographic printing took over, would print material in vernacular languages but through typographical printing machines. Hence, the compositors who were not deemed suitable enough for government or mission work would seek employment in vernacular typographic presses. This should not be generalised to include reputable printing presses like the Munshi Newal Kishore Press. This also should not be generalised to include lithography presses, where most vernacular language material was catered for, owing to the complexity of the vernacular alphabet and characters.

In our inquiry, the press in question is one that printed in moveable type print but was in the weaker range of the industry – one economising on all types of costs, including labour.

In such situations, certain templates were prepared, especially for borders and floral designs to go onto title pages. The variable text would be set by compositors and replaced on the blank part.

From the facts considered above, it appears that the Freemason emblem on the title page of the book in question must have remained as part of a template; reused to save effort, labour and wages.

Conclusion

In reaching the above conclusion, the following facts need to remain in mind:

- Hazrat Ahmadas was oblivious to what Freemasonry was all about until 1901 – two years after the publication of the book.

- He vehemently condemned Freemasons in his statement, eight years on from the publication in 1907. He clearly called it apostasy to join them.

- Had he been a Freemason, he and his Community would not have undergone the level of persecution they faced and still face in Muslim countries.

Also, there remain a few questions for the critics to consider:

- Do Freemasons wear their affiliation on their sleeve for all to know who they are?

- If one is a Freemason and wants to let the sovereign know, would their lodge not facilitate in communicating the message?

- If the affiliation of a Freemason to his cause is so overwhelming and the desire for public display so strong, would they not have the logo go on all correspondence or on title pages of all their books?

It’s important to find other title pages from this press which bear the same sign. I trust that the research into this will be ongoing.