Aizaz Khan, Missionary, Canada

وَ اِنَّ کَلَامِيْ مِثْلَ سَيْفٍ قَاطِعٌ

وَ اِنَّ بَيَانِيْ فِيْ الصُّخُورِ يُؤَثِّرٗ

“Indeed, my discourse is powerful like a sharp sword,

And surely, my arguments even penetrate the hardest hearts.” (Hamamatul Bushra, Ruhani Khazain, Vol. 7, p. 332)

Introduction

One day, in April of 1893, two highly reputable Christian missionaries were having a dispute about an upcoming debate between Christianity and Islam. Their dispute went something like this:

Dr. Henry Martyn Clark: Some men from Qadian are here to settle the date and conditions of a debate. Come, let’s settle the matter with them.

Abdullah Atham: What have you done, Dr. Clark? If you had chosen any of the other one hundred maulvis, I would not care at all. But why have you deliberately put your hand in a wasp’s nest? To meddle with Mirza Qadiani is not easy at all—in fact, it is extremely difficult! Near impossible! You’ve caused this chaos, so go handle it yourself! I will not go now; nor will I be a part of this debate!

Dr. Henry Martyn Clark: Abdullah! You are the warrior of Christianity, and only you can handle this task. I’ve gone through the trouble of helping arrange this event by placing my trust in you […] and yet you have the audacity to refuse to be a part of it? Mark my words, you will certainly be a part of this debate!

Hearing this, Abdullah Atham reluctantly followed Dr. Clark back to his home, where some companions of the Promised Messiahas were awaiting their arrival. As soon as he sat to settle the date of the debate, the following words escaped his lips: “Oh! I am indeed a dead man!!” (Hayat-e-Tayyibah, p. 150)

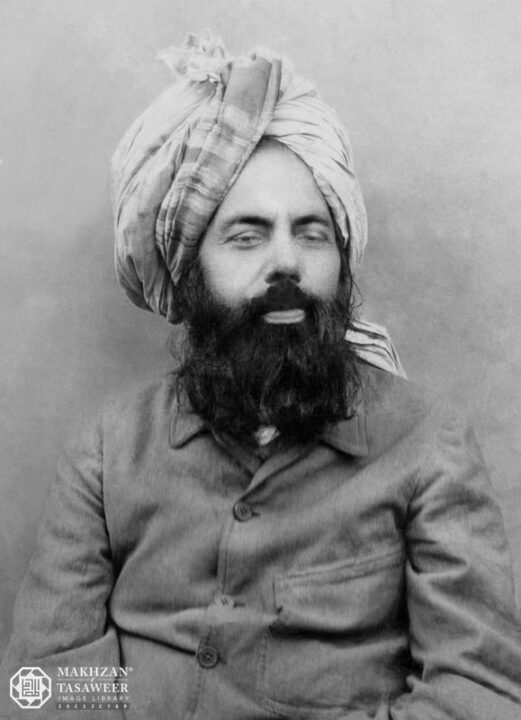

This exchange occurred prior to the famous “Jang-e-Muqaddas” (Holy War) debate between Christian missionaries and the Promised Messiahas in 1893. The natural question that arises here is, why was Abdullah Atham so terrified of debating the Promised Messiahas? What was it about the Promised Messiahas that instilled fear into the hearts of his opponents? A significant part of the answer to this question is what this article will attempt to elucidate: The Promised Messiah’sas Ilm al-Kalam (scholastic theology or dialectics) and method of argumentation.

An important note

It must be clarified here that the Promised Messiahas, when addressing the maulvis, would occasionally adopt their style to counter their arrogance and presumed knowledge. However, he typically did not adhere to their pre-set criteria; instead, his discourse was devoid of any affectation (takalluf) and stood out as uniquely beautiful and impactful. The Promised Messiahas was not a mutakallim (one who dialogues) in the colloquial sense, nor did he ever claim to be; rather, as a prophet sent for the revival of Islam and to bring about its ultimate victory, the Promised Messiah’sas status is unimaginably beyond the rank of a mere debater. Bestowed the title of Sultan-ul-Qalam (The champion of the pen) by Allah Himself (Tadhkirah [English], p. 91), the Promised Messiah’sas Ilm al-Kalam – as we refer to it for the sake of consistency and familiarity – was established and inspired by Allah the Almighty and is in a rank of its own. The Promised Messiahas writes:

“I particularly experience God’s miraculous power when I put my pen to paper. Whenever I write something in Arabic or Urdu, I feel as if someone is instructing me from within.” (Nuzul-ul-Masih, Ruhani Khazain, Vol. 18, p. 434)

What is Ilm al-Kalam?

The term Ilm al-Kalam comprises two separate words: Ilm and Kalam. The meanings of the word Ilm include: knowing, finding out, and enquiring. It can also mean knowledge, wisdom, intelligence, and acquaintance (Feroz-ul-Lughaat, Urdu Jami’, p. 845). The word kalam, literally, means ‘discourse’ or ‘to converse’. In the Urdu lexicon, kalam has been defined as, ‘speech, discourse, and conversation’ (Ibid, p. 939). Al-Munjid, the Arabic lexicon, has defined the literal meaning of al-kalam as ‘al-qawl’ (saying or discourse) (Al-Munjid, p. 695).

In terminology, when the words ‘ilm and kalam are used together as a compound word, a particular category of ‘ilm or knowledge is implied. Syed Suleiman Nadvi writes in the preface to Allama Shibli Nomani’s book, “Al-Kalam”:

“Ilm al-Kalam is an art in which rebuttals are given to allegations and doubts raised by opponents of religion and in which the truthfulness of religious doctrines is proved using traditional and rational evidence.” (Preface to the book Al-Kalam, 2012)

In essence, Ilm al-Kalam is the method used by religious scholars to defend Islamic doctrine through powerful and well-grounded responses and to prove the truthfulness and superiority of Islam as a divinely revealed religion.

Purpose of Ilm al-Kalam – Resolving religious disputes

Religious dialogue and the use of Ilm al-Kalam are the first steps in resolving religious disputes and completing an argument (اتمامِ حجت) on an opposing party. The Promised Messiahas states:

“This has been the way to resolve all religious issues from time immemorial: that when two parties differ, they first try to decide on the basis of the record [i.e., traditions] available in the scriptures. When a decision cannot be reached on the basis of written evidence, they turn to reason and try to decide with rational arguments. Then, when an issue cannot be resolved with reason, they seek a heavenly decision and take the heavenly signs as the arbitrator.” (A Gift for the Queen, p. 24)

The Promised Messiah’sas principles of argumentation

The Promised Messiahas has not expressly defined the term Ilm al-Kalam in his writings. However, if we analyse his writings as a whole, we find that his method of argumentation comprises – but is not limited to – the following foundational components:

Every statement during a dialogue must be based on viable proof, and every tenet of faith (عقیدہ) must be proven with clear and manifest arguments.

Both traditional or textual (نقلي) and rational (عقلي) arguments should be presented during dialogue; only logical arguments should be presented to those who are not confined to, or bound by, any revealed book.

Note: The word نقلي (“traditional”) refers to arguments extracted from a religious scripture or text that someone is bound by and cannot dismiss or refuse to accept, i.e., the holy books and sacred texts of various religions.

Whereas refutations must be presented to arguments posed by the opposing religions, the superiority and greatness of one’s own beliefs should also be proven. (Kasr-e-Saleeb, Ataul Mujeeb Rashed, p. 11)

The importance of these foundational components of argumentation can be understood from the fact that the Promised Messiahas argues that there are only three ways of satisfying the human intellect, without which a person’s erroneous beliefs, which have been passed on to them and inherited through generations, simply cannot be rectified. The only three ways to emancipate the human mind are:

Traditional proofs (نقلي دلائل) i.e. first the Holy Quran and then those Ahadith that are in harmony with Qur’anic teachings and principles

Rational proofs (عقلي دلائل)

Heavenly proofs, i.e., fulfilled prophecies or miracles that one witnesses. (Malfuzat, Vol. 3, pp. 293-296 (1988 edition)

Reformation of religious dialogue

In the time of the Promised Messiahas, and in the era before his advent, religious scholars would engage in inter-religious dialogue with the sole intent of embarrassing their opponents, not with the intent of guiding them. Furthermore, scholars would pick points from external sources and attribute them to their own religions, thereby forcing appeal and attraction in an artificial and deceitful manner. Consequently, seekers after truth were unable to decide between the various religions. The Promised Messiahas reformed this style of religious dialogue and proposed a process by which the truth of a certain religion could be determined. Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra states, regarding this, that the Promised Messiahas turned the tables on this useless tactic and stated that by exposing the weakness of a person, the truth of a religion cannot be established, and also that debating on one single matter cannot manifest the truth of a religion. The process by which one recognises the truth of a religion should comprise the following points:

Witnessing/Personal Experience: for example, if the purpose of the religion is to grant someone closeness to Allah, then it should prove that by following it, nearness to God will be attained. Simply a few moral and philosophical teachings cannot prove a religion to be true.

The claim and the support for that claim should both be present within the revealed book of the religion—the wisdom behind this is that God’s word cannot be without supportive evidence. “It shall, however, never be allowed that one should make up some argument oneself to try and help the Revealed Book in a way similar to the help offered to a weak and helpless man, or a corpse that is put in motion with the support of one’s own arm and one’s own hand.” (The Holy War [Jang-e-Muqaddas], p. 28)

Every religion that claims to be universal should prove that its teaching satisfies every natural inclination of man and that it fulfils every need of man. (Hazrat Masih-e-Maud Ke Karnamay, Anwar-ul-Ulum, Vol. 10, pp. 192-193)

Revolutionary Method of Argumentation

The methodology outlined above was such that whether or not the opponents accepted its conditions, their own faiths were suddenly in danger. The second condition alone (to prove each and every single one of their arguments from their own revealed scriptures, with claims and supports) put opponents in a dilemma. Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra writes:

“This was such a solid principle that advocates of other religions could never reject it. If they did, they would in effect be admitting that the claims they make on behalf of their religion are not to be found in their scriptures. And, if the claims are to be found in the scriptures, then why are the arguments missing from them?” (Invitation to Ahmadiyyat, pp. 167-168)

Opponents of Islam used to make up stories and attribute them to their faiths deceitfully in order to appeal to the general population. The thing they feared most was that they would be exposed, and they thus wished not to accept this condition of dialogue. Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra states, regarding this, that:

“When this principle was applied to other religions, it was found that almost 90% of their claims could not be found in their respective scriptures. As for the claims that were found in the scriptures, almost 100% were without accompanying arguments.” (Ibid., p. 168)

Further, regarding the magnificence of the Promised Messiah’sas Ilm al-Kalam, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra says:

“They [the opponents] were so dispirited that to this day they have not found a way to counter this point, nor will they ever do so. This theological discourse is so perfect and superior that it cannot be rejected, nor can falsehood be upheld in its presence. As this criterion is employed more and more, advocates of false religions will withdraw from the field of religious debate, the vulnerability of these religions will become further apparent to their followers, and the world will witness the fulfilment of God’s promise that Islam will triumph over all religions.” (Ibid., pp. 168-169)