Asif M Basit, Ahmadiyya Archive and Research Centre

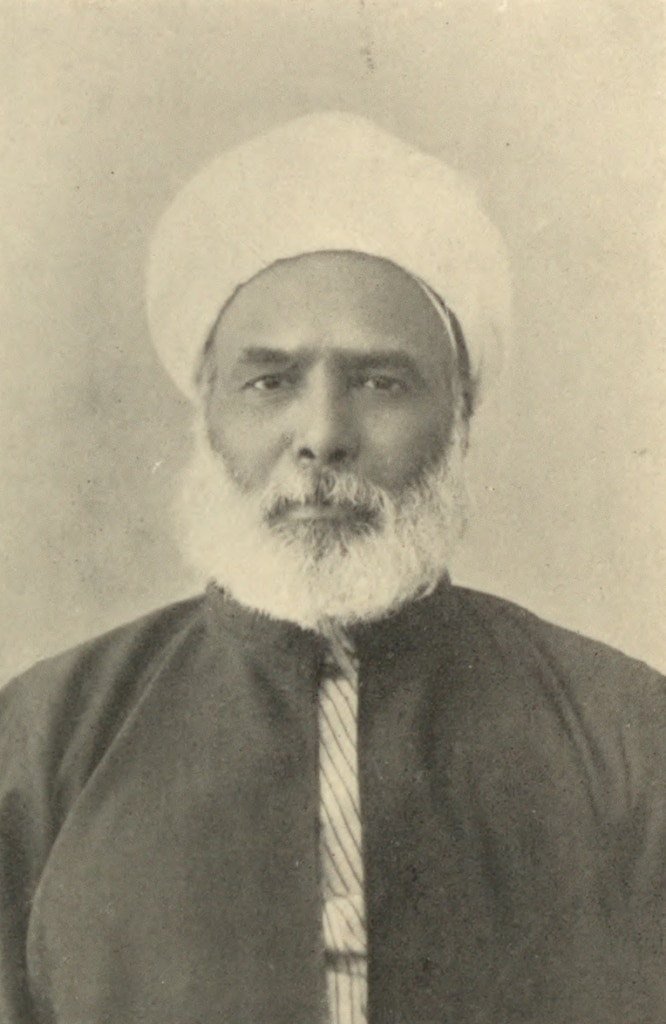

Hazrat Mufti Muhammad Sadiqra was one of the earliest companions of Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the Promised Messiahas, who had given up his career in the government service to serve his master.

Alongside a number of other services, his proficiency in the English language got him the opportunity to become a window that opened into the Western world for Hazrat Ahmadas.

John Hugh Smyth-Pigott’s claim of divinity, Dowie’s claim of being the Elijah, and details of the religious atmosphere of the West, were brought to the notice of Hazrat Ahmadas by Mufti Sadiqra. His role was what would today be termed as private secretary.[1]

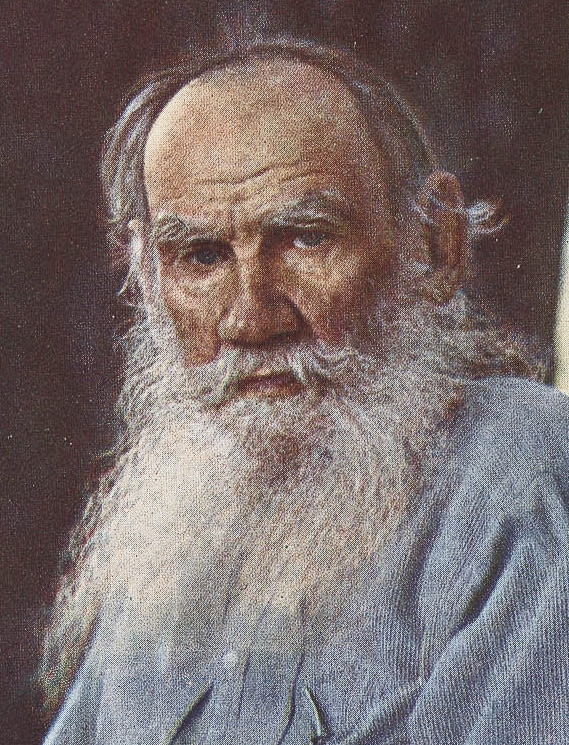

In this role, he wrote extensively to influential figures of the Western world and introduced them to Hazrat Ahmad’sas teachings as the revivalist of faith – awaited by all religions to appear in the latter days. One such figure that Mufti Sadiqra came in contact with was Count Leo Tolstoy – more commonly known as a novelist but actually a man with deep religious aspirations.

A quick glimpse into Tolstoy’s life shows how he had journeyed through his life from being an Orthodox Christian to becoming a Christian anarcho-pacifist, to a self-styled socio-religious reformer. He was excommunicated from the Russian Orthodox Church for his “flawed” beliefs in 1901 – just two years before Mufti Sadiqra got in touch.[2]

Some scholars debate that Tolstoy was not excommunicated by the Church but had instead voluntarily parted ways with institutionalised Christianity. Whatever the case, the divorce had brewed over decades and did not just happen overnight; although his novella Resurrection is said to be the trigger.

Tolstoy, in his autobiographical accounts, refers to an episode of moral crisis in 1870, which he sees as a blessing in disguise that brought about spiritual awakening in his heart and soul. It was from this point onward that he lost faith in the orthodox Christianity’s dogma and ritual, and started paving way for his own personal understanding of Jesus and his teachings.

He laid out his personal beliefs in his work What I Believe (1884) where he emphasises on understanding Jesus’s ethical teachings with special reference to his Sermon on the Mount. Tolstoy understood the teaching of presenting the other cheek to have deeper meaning and a call to “non-resistance to evil by force”.

Tolstoy remained a Christian all his life despite having given up belief in orthodox Christian dogma by the age of 18. He was in search of a better understanding of life – something that orthodox Christianity had failed to provide. The young, disgruntled Tolstoy may have broken religious bonds with the institutionalised church, but emotional ties remained intact and his wayward soul led him into a state of depression. This happened in 1877 – the moral crisis that he refers to, while the spiritual awakening came from reconnecting with Christianity when he visited Optina Pustin Monastery in the same year.

But this reconversion too did not last very long, and only a couple of years after, he was grappling with rationalising his faith.

Looking back at this bumpy journey of his spiritual life, he wrote in 1884:

“I have lived 56 years and, with the exception of the last 14 or 15 years of my childhood, I was for 35 years of my life a nihilist in the literal sense of the word – that is to say, I was neither socialist nor revolutionary, in the commonly-accepted sense of the word: to me, nihilism signified the absence of all religion …”[3]

About what he had reached, he said:

“I believe in one incomprehensible and benevolent God; I believe in the immortality of the soul and in eternal retribution for our deeds; I do not understand the mystery of the Trinity and the birth of the Son of God …”[4]

Tolstoy’s autobiographical accounts lead one to realise that he was inspired by messianic aspirations where he envisaged “the establishment of a new religion suited to man’s level of development …”.

He expressed his desire quite openly to “work consciously to bring man back to religion, such is the basis of the idea which I hope will occupy my enthusiasm”.

This messianic idea dictated most part of his latter life – the force of which led him to explore other religions like Islam, Bahaism, and Hinduism.

He had ended up believing that it was not reasonable to believe that “God had come down to earth and then gone back up to heaven”; nor was he ready to believe in resurrection, as he saw it “impossible to go up to heaven because there isn’t one, just our illusion of a canopy of heaven …”

In his quest for the true meaning of Christianity, he had realised that the actual beliefs had been corrupted by the institution of the Church to suit their political and economic agendas. What he didn’t realise was that he had reached very close to the teachings of Hazrat Ahmadas in this regard.

It was at this point that Mufti Sadiqra reached out to Tolstoy offering him the teachings of the Promised Messiahas who had demystified not only the Christian Jesus, but the orthodox Muslim one too.

For this brief study, we take three samples of Tolstoy’s correspondence before turning to his correspondence with the Ahmadiyya mission through Mufti Sadiqra.

Tolstoy and the Baha’i faith

Tolstoy first heard of the Baha’i faith in 1901, although he had been familiar with Babism from earlier on, and also impressed by the Babi beliefs. We know this from his reply to a Gabriel Sacy, a Frenchman of Syrian origin, and a Baha’i.

Sacy, writing to Tolstoy on 13 May 1901, expressed his acceptance of Tolstoy’s concept of a unified faith. In doing so the Baha’i admirer of Tolstoy conforms to Tolstoy’s understanding of Christianity, rather going beyond in saying that Jesus “represents a very important Manifestation of the Divine Essence, destined to lead humanity towards progress”.

Tolstoy, replying to his newfound Baha’i friend on 10 August 1901, tells him that he has read everything on Babism, but “What is Baha’i?”

Tolstoy cannot keep his aspirations inconspicuous and tells Sacy that “your concept of messianism inspires me, as well as Babism to which you belong.” Tolstoy saw in Babism/Bahaism so much common with Christian anarchy, that, he thought, “… sooner or later they are destined to join forces.”

A few months later, Tolstoy is visited by another Baha’i, a Persian merchant, Mirza Azizullah Jadh-dhab Khurasani, who gives a detailed account of this meeting in his diary. Jadh-dhab arrived in Yasnaya Polyana on 17 September, and the meeting took place the following day on 18 September 1902.

Tolstoy showed a great deal of interest in the Baha’i faith, especially in whether it was being accepted by non-Islamic nations. Jadh-dhab, with an equal level enthusiasm, explained:

“Among Jews many have accepted the Baha’i Faith, in Hamadan, Yazd, Tehran, Khurasan (in Iran), likewise in the Caucasus and America. I myself am a Jew from Khurasan. Among the Zoroastrians many have become Baha’is, both in Iran and in Bombay. Among the Christians, there are some in America, Paris, Germany and London, as well as Egypt.”

At the close of the meeting, Tolstoy is asked what he thinks about Bahaullah.

“How could I deny him? I have wished to educate certain Russians, and I have been subjected to house-arrest, with Police installed in order to ensure no one visits me. Obviously this cause will conquer the whole world. I myself have already accepted Muhammad.”

Tolstoy here is referring not to Bahaism, but his own self-conceived messianic movement that will “conquer the world”. With the Bahais, he was merely testing the waters it appears, as in the following few years (1903-1906) he not only lost interest in Bahai faith, but developed a certain level of aversion towards it.

On 4 April 1904, a French lawyer, Hippolyte Drefus, sent Tolstoy his translation of Bahaullah’s Kitab-i-Iqan, entiltled Le Livre de la Certitude. Tolstoy’s reply must have shocked his Bahai admirers:

“Thank you for sending me the book by Bahaullah. I regret that I am obliged to say that reading this book has completely put me off Bahaullah’s teachings. This book merely contains insignificant and pretentious phrases which have no other purpose but to confirm the old superstitions which are completely devoid of any moral and religious content, in the true sense of the word.”

Tolstoy was most certainly trying to assess if Bahaism could provide him the ecology for his own messianic movement. Having seen no prospects, he wrote, on 31 July 1904, to his friend, the American author Ernest Crosby:

“Dear friend, I was very interested by Bahaism, and I know all about it. I believe this sect has no future …”[5]

The fling of Bahais and Tolstoy, despite mutual flattery, fell flat – both saw no future for their agendas in each other. Tolstoy had his own messianic worldview where he was the central figure, and Bahaism had its own, where Tolstoy was not the central figure – nor was there room for anyone other than Bahaullah to take the centre stage.

Tolstoy and Islam

While in Jadh-dhab’s account we find Tolstoy admiring Islam and having “accepted” Muhammad, the prophet of Islam, his mercurial ideologies seem to have shifted soon after. A conversation between Tolstoy and his ardent admirer SD Nikolayev, heard and reported by Tolstoy’s doctor Makovitsky, explains Tolstoy’s ideas on Islam. Tolstoy is reported to have said:

“I consider Islam as a form of Christianity, which has emerged from apocryphal Christian traditions …

“Whatever has passed into Islam Christianity is good, whatever comes from Muhammad is coarse.

“… The doctrine of the Muslim sects of Babism is purely Christian.”[6]

We find here Tolstoy’s rejection of not only Islam, but Christianity and Babism too – Babism being the term he interchangeably uses for Bahaism.

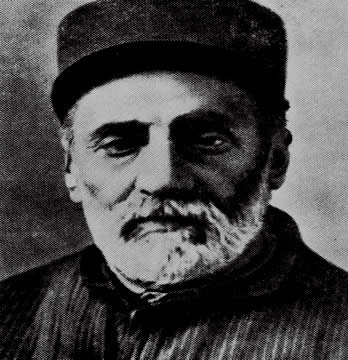

Then lands on Tolstoy’s desk, in the early summer of 1904, a letter from Muhammad Abduh (1849-1905) – an influential ideologue of Islamic modernism, and later the Grand Mufti of Egypt.

Muhammad Abduh was a strong advocate of unity of all religions for he focused first on the sectarian divide within Islam before turning to other faiths. Christianity being the second largest religion in his homeland, he invested his thought into Christian-Muslim harmony and a prospective unity of both Abrahamic cousins.

A protégé of Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, Abduh stood for what is rightly termed today as political Islam. With a strong pan-Islamic worldview, Abduh saw Islam as the one faith that should dominate the world in every way – from faith to political ideology, from economics to societal structure, from legislation to judicial processes.

While attracting a following from within the Egyptian intellectual circles, Abduh’s ideology earned him a great deal of notoriety in the predominant clergy of Egypt who went so far as to declare him an infidel, and driving him to live a life of exile in Paris for a period of several years.

In his desperation to materialise his imagination of a world unified under his Islamic worldview, Abduh ended up not only exploring the Freemasonry but also signing up for it and becoming an active member of the Lodge.[7]

He must have come across Tolstoy’s works and messianic thought earlier, but he seems to have held back his admiration until 1904, when he first wrote to the anarcho-pacifist. His first letter reached Tolstoy through a friend, art historian Sidney Cockrell, and Tolstoy replied to the intermediary first:

“I have now received the Mufti’s letter and I am very grateful to you for sending it to me. The Mufti’s letter is so Oriental in its praise that it is difficult for me to answer it. But I will try to do so and I am very glad to communicate with such an interesting person.”[8]

The following day, 13 May 1904, Tolstoy wrote directly to Muhammad Abduh, who was then the Grand Mufti of Egypt:

“I have received your good and overly praiseworthy letter and I hasten to reply to assure you that it has given me great pleasure in bringing me in into contact with an enlightened man, though of a different faith from that in which I was born and brought up, but of the same faith with me, for faiths are different and there are many of them, but there is only one faith, the true one. I think I am not mistaken in assuming, from your letter, that the faith I profess is the same as your faith, and consists in acknowledging God and his law, in loving one’s neighbour and doing others what one would like them to do to you. I think that all true religious principles flow from this, and that they are the same for Jews, Brahmins, Buddhists, Christians, and Mohammedans alike. I think that the more religions are filled with dogmas, precepts, miracles, superstitions, the more they divide people and even create unfriendliness, and, on the contrary, the more they are purified, the closer they reach the ideal goal of mankind – common unity. That is why your letter was very pleasant to me, and I wish to remain in communication with you…”[9]

Historians and Tolstoyans seem not to find the trigger point of the correspondence between the two, and what might have led to it. This cannot be possible without looking into what sculptured the Muhammad Abduh as we know him.

Abduh was a close friend and confidant of Wilfrid Blunt – an English poet, traveller and horse-breed aficionado. Blunt, much like Tolstoy, remained unsettled in his sense of belonging to any faith – born and raised a Christian, turned atheist, supposedly accepted Islam, but sought the blessings of a priest on his deathbed.

Known to be an anti-imperialist, Blunt supported movements and uprisings brought about by Egyptian nationalists. He was close to Cromer, the Counsul-General of Egypt and promoted Abduh in the circles of the British bureaucracy of Egypt. Blunt and his wife were both fanatic admirers of Tolstoy.

In his diary, later published as My Diaries, Blunt writes on 28 November 1895:

“Today, I went to Cairo and saw Lord Cromer … He then talked of other matters and of the possibility of Mohammed Abdu being head of the Awkaf. This I, of course, strongly commended.”[10]

Abdu’s vision of a liberal Islam endeared him to the British, Lord Cromer (Counsel-General of Egypt) in particular who held very strongly the opinion that Egypt could not catch up with the modern world without breaking ties with Islam. Abduh, vocal as he was about his political Islam, was certainly seen as helpful in such colonial agendas.

Blunt’s diary is full of intelligence provided by Abduh from the nationalist and Khedive circles, and passed on to the likes of Cromer.

Blunt and his wife Anne were also friends with Cockerell who visited the couple in Cairo in early 1904. During this visit, he was introduced to Abduh who, as known from Cockerell’s letter to Tolstoy on 2 May 1904, handed him a letter to be sent to Tolstoy.

This was happening at a time when Tolstoy had only just been excommunicated by the Russian Orthodox Church and was now fully active in setting up his movement to materialise his concept of a unified religion where his messianic ideals left him in charge of its global implementation. Cockerell, a diehard Tolstoyan, wrote in the aforementioned letter to Tolstoy:

“I was lately in Cairo and [Abduh] entrusted me with the enclosed letter to be forwarded to you …

“At a time when your brave statement about the unfortunate conflict in the East may have aroused the hostility of many, you may be supported the sympathy expressed by a wise man of another religion who has suffered because his principles have not always been shared by his countrymen.”[11]

So here we have proponents of Tolstoyan worldview trying to marry a reformist ideology to Tolstoy’s messianic ambitions.

Before closing this section, let’s have a quick look at the Grand Mufti’s flirtations with Tolstoy in the letter that Tolstoy replied to:

“Although we have not had the pleasure of meeting in person, your spiritual world is familiar to us. The light of your thoughts has shone upon us, and the sun of your ideas has risen in the heavens, which has linked you with enlightened minds.

“God has shown you the way to understand the mysteries of human nature, according to which He created men, and He has enlightened you as to the purpose to which He is guiding the human race.

“… By turning your eyes to religion, you have torn the veils of oblique traditions and come to understand the essence of monotheism.

“… You raised your voice to call people to what God had directed you to do, and you were the first to follow the path, drawing them along with you …”[12]

“The Mufti’s letter is so Oriental in its praise that it is difficult for me to answer it …,” said Tolstoy; the author finds it difficult to even copy it here.

The letter is flattery at its best (or worst rather) where Muhammad Abduh is searching for a scope in someone who, in return, is seeking the same for his own messianic ambitions in Abduh’s ideology.

Only two letters are known to have been exchanged before the two revivalists lost touch. They could not find in one another the prospects of their respective desired outcomes.

Tolstoy and Hinduism

From Karl Marx and Engels to Tolstoy, India had remained a favourite model for analysing colonial rule – thanks to the diverse and pluralist nature of the Indian society.

Differing from the Marxian theory of India’s future, Tolstoy believed in India’s independence from Colonial rule but through peaceful means. For fruition of his global worldview – stemming from Christianity and creeping into world religions – Tolstoy saw in India a laboratory where his messianic ideas could potentially bring back gains.

The irony was that Tolstoy yearned for a socio-political-economic movement to be launched in the name of religion. This led to his correspondence with two Hindus, which had started off with what he titled “A letter to a Hindoo”.

Taraknath Das (also spelled Tarak Nath Das), a Bengali revolutionary and anti-colonial activist Hindu, had settled in Canada and started a journal titled Free Hindustan. While trying all possible means for his independence movement, Das decided to reach out to Tolstoy and use his global influence.

Das wrote a letter to Tolstoy on 24 May 1908 asking to intervene in the Indian question:

“… You did immense good by the literary works about Russia. We pray to you that if you have time at least to write an article about India and thus express your views about India!

“By the name of the starving millions I appeal to your Christian spirit to take up the cause.”[13]

Tolstoy replied through a long treatise and titled it A letter to a Hindoo, published Das’s Free Hindustan.

While Das was expecting a revolutionary solution from Tolstoy, he was on the contrary advised that the solution to India’s problem lay in a non-violent retaliation: “Forcible resistance to evil-doers involves such a contradiction as to utterly destroy the whole sense and meaning of love”, Tolstoy had written back.[14]

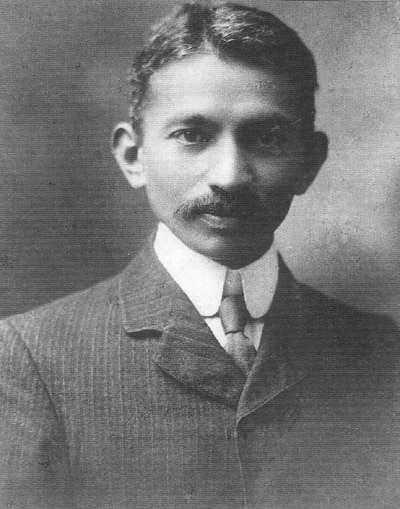

Tolstoy’s reply might not have met Taraknath Das’s expectations, it most certainly touched the heart of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, then a young lawyer in South Africa trying to carve a way through colonial atrocities – both in South Africa and back home in India.

Gandhi was in London when he stumbled upon this correspondence, published in December 1908. He was already an admirer of Tolstoy for his fictional works, but more so for The Kingdom of God is Within You – a spiritually motivated work of Tolstoy.

This letter of Tolstoy, closer to home as it was, inspired Gandhi to write to Tolstoy, hence starting a long trail of correspondence to span a period of two years – until November 1910, when Tolstoy died.

From his first letter to Tolstoy, dated 1 October 1909, Gandhi seems deeply influenced by the idea of non-violence in the face of violent suppression: “… some of us at least have seen most clearly, that passive resistance will and can succeed where brute force must fail.”[15]

Tolstoy must have found a loyal disciple in Gandhi when, in the same letter, Gandhi advises Tolstoy to tread with political correctness:

“I would also venture to make a suggestion. In the concluding paragraph you seem to dissuade the reader from a belief in reincarnation…

“Reincarnation or transmigration is a cherished belief with millions in India, indeed in China also.

“… My object in writing this is not to convince you of the truth of the doctrine, but to ask you if you will please remove the world ‘reincarnation’ from the other things you have dissuaded your reader from.”[16]

Tolstoy, in his reply dated 7 October 1909, wholeheartedly accepts Gandhi’s offer to have A letter to a Hindoo translated into Indian vernacular and publicised widely. In doing so, he also incorporates Gandhi’s proposal for political correctness:

“… of course, I would accommodate you, if you so desire, to delete those passages in question. It will give me great pleasure to help your edition. Publication and circulation of my writings, translated into Indian dialects, can only be a matter of pleasure to me.”[17]

By the spring of 1904, Gandhi was identifying himself as a “devoted follower” of Tolstoy in his letter dated 4 April.

By the summer of 1910, Gandhi had created, with his friend H Kallenbach, a shelter home for passive resisters in South Africa, and named it Tolstoy Farm – known from Gandhi’s letter of 15 August 1910.

This sample of Tolstoy’s outreach to India through Gandhi, is yet again not only correspondence, but an attempted collaboration between two “mahatmas” – or venerable, great souls – both yearning for a messianic objective.

Tolstoy and Ahmadiyya Islam

We place Tolstoy’s correspondence with the Ahmadiyya missionary, Mufti Muhammad Sadiqra, at the last as it differs in attitude and approach from the three aforementioned religious movements that came in touch with the great writer and thinker of his time – the time that happened to coincide with the budding of the Ahmadiyya community.

What brought about this correspondence, initiated obviously by Mufti Sadiqra, is hard to put a finger on. However, we can loosely identify the reasons behind this initiative.

In replying to the Russian Orthodox Church of excommunication, Tolstoy wrote a response titled My reply to the Synod.

He addressed the charge sheet brought against him, and that led to his excommunication in detail, but to quote a paragraph from it should suffice to state where Tolstoy stood in terms of his belief:

“Then it is said that ‘I deny God worshipped in the holy trinity, the creator and designer of the universe; I deny Lord Jesus Christ, God-man, redeemer and savior of the world, who suffered for us men and for our salvation, and was raised from the dead; I deny the immaculate human conception of Lord Christ, and the virginity, both before his birth and after his birth, of the Most Pure Mother of God.’

“In regards that I deny the incomprehensible trinity and, having no meaning in our times, the fable of the fall of the first man, as well as the blasphemous story of a God being born of a virgin to redeem the human race – that is perfectly true…”[18]

He went on to describe that he did not believe in all the superstitions attached to the rituals like baptism and eucharist, and also that he found the concept of resurrection unreasonable.

Seeing in Tolstoy a true Christian who, if guided, should ultimately become a true Muslim, Mufti Sadiqra seems to have written to him.

The collection of Tolstoy’s letters includes his replies but not the letters written to him by Mufti Sadiqra. However, Mufti Sadiqra recorded his initial letter in his quasi-autobiography, Zikr-i-Habib:

“Your Highness!

“I read your religious views in the recently published British Encyclopaedia vol. 33. I am glad that real gems can be found bowing to the manifestation of the true deity even in the darkness created by the concept of Trinity in Europe and America. Your thoughts about true ‘well being’ and prayer are exactly the same as of a true Muslim believer. I completely agree with you that Jesus Christ was a spiritual teacher but to consider him god or to worship him like a god, is the greatest disbelief.

“Furthermore, I wish to inform you with great pleasure that the discovery of the tomb of Jesus proves substantially that he died a natural death. The tomb has been discovered in Kashmir. This research has been publicised by Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the greatest protector of the unity of God, and to whom the Lord Almighty has given the title of the Promised Messiah because he is replete in his love for the one true God.

“Allah appointed him, as a person from God, an inspirer and a reformer of the age and God’s true messenger. God will bless all those who will believe in this prophet. Whosoever will deny him, will face God’s wrath.

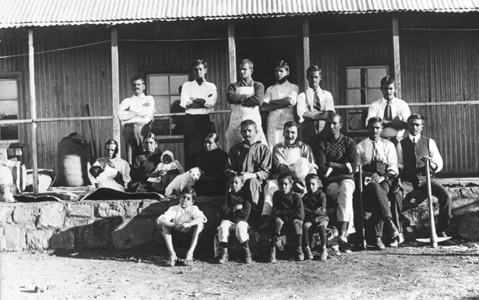

“I am sending you in separate packet, a picture of this holy person from god along with the picture of the tomb of Jesus. On receiving your reply, I would be glad to send you more books.

“I remain your well wisher,

“Mufti Muhammad Sadiq of Qadian 28 April 1903”[19]

The same issue of Review of Religions includes a reply from Tolstoy:

“Dear friend! Your letter along with Mirza Ghulam Ahmad’s picture and a sample of the magazine Review of Religions has been received. To engage in the proof of the death of Christ or in the investigation of his tomb, is a futile effort because an intelligent man can never believe that Jesus is still alive… We need reasoned religious teaching and if Mr Mirza presents a new reasonable proposition then I am ready to benefit from it. In the specimen number, I approved very much two articles, ‘How to get rid of the Bondage of Sin’ and ‘The Life to Come’, especially the second. The idea is very profound and very true. I am most thankful to you for sending me this and am also grateful for your letter.

Yours Sincerely, Tolstoy, from Russia. 5th June 1903.”

While I have not been able to trace the wording of the reply reproduced in the above cited issue of the Review of Regions, I have however come to know that Tolstoy’s letters have been reproduced and translated by more than one source. Mufti Sadiq’s letter and Tolstoy’s reply were published first in the Urdu language newspaper Al Hakam in 1907 as an Urdu language rendering. The ones reproduced in Review of Religions are a retranslation from the Urdu version as that is all that was available to them at that time.

The slight discrepancy in the text can be down to this factor, as the ellipsis occur at the place they belong, as we can now confirm from the original, published correspondence by the Russian State Library, by State Publishing House of Fiction.

For the purpose of this paper, I will refer to the letter published by the Russian State Library:

“То Mufti Muhammad Sadig [sic].

“Dear Sir, I received your letter as well as the leaflet with the portrait of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad and lately a specimen number of the “Review of Religions”.

“The proofs of the death of Jesus and the pretended discovery of his tomb are quite useless because no reasonable man can believe in resurrection. What belongs to the man Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, w[h]ich you call the promised Messiah, all what you write about him and what is written in the leaflet has no interest whatever for me.

“We need no Messiah, we need only reasonable religious teaching and if Mirza Ahmad can teach men some new and reasonable doctrine I will be very glad to profit by it, but I know nothing of it. In the “Specimen Number” I approved very much two articles: “How to get rid of sin” and “The life to come”, especially the second. The idea is very profound and very true.

“Thank you very much for sending this specimen, as well as for your letter.

“Yours truly

“Leo Tolstoy

“5 Juny [sic] 1903.”[20]

It is quite evident from Tolstoy’s reply, as confirmed by Piotr Stawinski, that he was not acquainted to the Ahmadiyya community, its founder and his beliefs – otherwise there was no reason for criticising the belief in resurrection.

The next reply from Tolstoy, to Mufti Sadiqra, is dated 23 August 1903:

“Mufti Muhammad Sadig [sic].

“Dear sir,

“I received your letter and the 12 № of the Review of Religions and thank you for both. Many articles are very interesting, but I am sorry that they are for the most part polemic against the Churches. I don’t say that they are not convincing, but I think that they are useless. I read also ‘The teachings of the promised Messiah’. It is quite true that they don’t contain anything quite against reason but I have not found in them anything new or expressed better than it was expressed before.

“I quite agree with you that the greatest evil of our time is the absence of true religion, and I think that every person which has in itself a religious feeling must try to communicate it to his neighbours by all means, especially by a good life. And that is all what we want and therefore ought to do in our time.

“Yours truly Leo Tolstoy.

“23 August 1903.”

The correspondence seems to have went on into 1908 where Mufti Sadiq, like a perseverant missionary, continued to send the Review of Religions to Tolstoy. There also seems a change of heart when he writes back:

“Dear Sir,

“I thank you for the Review of Religions.

“I am very interested in your work.

“Do you know the doctrine of Baha Ullah and what do you think of it?

“Yours truly

“Leo Tolstoy.

“2 February 1904.”[21]

Tolstoy’s in-house physician, DP Makovitsky kept a diary of his sayings and musings. Through these diaries, we see Tolstoy referring to the Review of Religions and admiring the works published therein, albeit sometimes with a pinch of salt.

On 17 May 1905, Tolstoy is recorded to have remarked:

“In the Review of Religions, there is an article about marriage among Mohammedans (when Nikolayev arrives, it will be necessary to tell him to translate this article). Their highest (ideal) is monogamy, and only for the weak is regulated polygamy allowed. The author asserts that they are superior to church Christians who have real polygamy. And a particular good article about the lack of attention to women’s shame on the part of doctors.”[22]

He remained in the spell of the article and the Makovitsky’s entry in 25 May 1905 reads:

“L.N. [Tolstoy] again praised the article in the Review of Religions on the Mohammedan view of marriage, against the hypocrisy of Christian monogamy.”[23]

Tolstoy refers to the same articles of the Review of Religions in November, and Makovitsky records on 9 November 1905:

“What solemnity, dignity, tranquillity to the Mohammedans (Tartars and others) have? In the Review of Religions, Mohammedan journal (a wretched journal, everything polemicizes against Christianity, and they have some kind of prophet), there were a number of articles against Christian false monogamy. Among the Mohammedans, the rule is monogamy, but in certain cases, due to weakness (the rich), polygamy is allowed. But on the other hand, they do not have houses of tolerance, like Christians.”

On this occasion, Tolstoy’s interlocutor, Sukhotin, asks: “But they are bachelors, aren’t they?”

To which Tolstoy replies: “And this is marriage. Polygamy. How surprised they will be in a hundred years that houses of tolerance could exist!”[24]

On 14 April 1907, Tolstoy’s interest in the Ahmadiyya magazine seems to have grown:

“L. N. instructed me to ask Chertkov to send his (L. N.’s) works to the editor of the Mohammedan Review of Religions (Quadian, district Gurdas pur India)…”[25]

This interaction between Tolstoy and the Ahmadiyya Muslim community continued, insofar as the author has been able to find, until at least 1908.

Conclusion

In the models of correspondence discussed above, the reader will notice that what caught Tolstoy’s attention in any religion was its plausibility to turn into the world order that he was imagining.

His heightened interest in Bahaism seems to be out of the flexibility that it provided to its believers, but as soon as he saw the scholastic tightening of loose ends in Kitab-i-Iqan, he lost interest.

If Muhammad Abduh stood for an Islam where one could feel free to wander into the lodges and sign up as a Freemason, Tolstoy was happy to use it as a springboard to dive into the waters of his own messianic ambitions. But Abduh had his own similar agendas, and Tolstoy was not there to follow.

Gandhi’s politically charged Hinduism appeared as one option but there seemed no room for a Russian prophet to lead the children of Mother India.

The first three of the above wrote extremely flattering letters to Tolstoy and were able to ignite his interest. On the other hand, the Ahmadiyya missionary’s correspondence had not even a trace of sycophancy and went straight down to inviting him to Islam as revived by Hazrat Ahmadas.

Tolstoy’s disinclination towards the Ahmadiyya Islam is evident from when he remarks with great distaste: “… they have some kind of prophet.”

It is not surprising to note the reaction of someone with his own messianic ideology to reject another who actually quite boldly claims to be the Messiah of the age.

When Mufti Sadiqra mentions his correspondence with Tolstoy, was he after the latter’s endorsement for the Ahmadiyya Islam? Most certainly, that does not seem to be the case. He only mentions him as one of the prominent persons whom he had reached out to in propagating the message of Islam Ahmadiyya.

[1] Details: Mufti Muhammad Sadiq, Zikr-i-Habib, accessible at www.alislam.org

[2] Tolstoy’s Religion in The Open Court, Vol 28, 1, pp 1-12

[3] Details: What I believe by Leo Tolstoy

[4] ibid

[5] Above quotes and further details: Leo Tolstoy and the Baha’i Faith by Luigi Stendardo

[6] Ibid, p 37

[7] Afghani and Freemasonry in Egypt by A Albert Kudsi-Zadeh, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol 92, No 1, pp 26-30

[8] Tolstoy, Letters, vol 75

[9] Tolstoy, Letters, vol 75, 1956

[10] My Diaries by Wilfrid Blunt, p 209

[11] Tolstoy, Letters, vol 75

[12] ibid

[13] Letter to a Hindoo: Taraknath Das, Leo Tolstoy and Mahatma Gandhi, ed Christian Bartolf, Gandhi Information Zentrum, Berlin, 1997

[14] ibid

[15] ibid

[16] ibid

[17] ibid

[18] My reply to the Synod by Leo Tolstoy

[19] First published in Al Hakam, Qadian, 30 June 1903, later rendered into English by the Review of Religions, February 2002

[20] Tolstoy, Letter, Vol 74

[21] Ibid, Vol 75

[22] U Tolstogo 1904-1910 by DP Makovitsky

[23] The reference above seems to be to Review of Religions vol 4, no 5, Objections against polygamy refuted p 164 – 174

[24] ibid

[25] ibid, parenthesis as in original