Iftekhar Ahmed, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre

As the twilight years of the 19th century cast their long shadows, a fervent call for an Islamic renaissance echoed across the Indian subcontinent. Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan, a visionary in the Muslim intellectual movement, dared to envision an audacious dream – an Islamic university unshackled from governmental oversight, a hallowed space akin to the grandeur of Cambridge and Oxford. Upon his demise, the mantle was taken up by Nawab Mohsin-ul-Mulk, who enshrined Sir Sayyid’s vision as a memorial within the aims of the Educational Conference movement.

Fundraising campaigns blanketed the vast expanses of India, rallying institutions, associations, aristocrats, and the common citizenry to this noble cause. In the city of Lahore, it was the esteemed Nawab Fateh Ali Khan who took up the charge, petitioning none other than Hazrat Hakeem Maulvi Noor-ud-Din, Khalifatul Masih Ira, the then supreme head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat, to seek his involvement and contribution as well as his Jamaat.

A resounding affirmation from Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Ira

In a letter dated 27 February 1911, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Ira responded to Nawab Fateh Ali Khan with a resounding affirmation:

“Esteemed Sir,

“assalamu alaikum wa-rahmatullahi wa-barakatuhu

“As I mentioned before, I am in full sympathy with the proposal for an Islamic university. I shall, insha-Allah, donate 1,000 rupees to this fund myself. Regarding the involvement of my Jamaat, I have published an announcement, a copy of which is enclosed herein.”

The announcement, a clarion call to the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat, echoed the importance of this noble endeavour:

“Since a general movement is currently underway to establish an Islamic university in India, and some friends have enquired whether we too should participate in this donation fund, this announcement is made for all those associates involved in this endeavour:

“Although the specific needs of our own movement are many, and our people bear a heavy burden of such donations, since the university movement is a noble cause, we deem it essential that our friends too participate – by pen, stride, speech and monetary aid.” (Badr, March 9, 1911, p. 6)

Accompanying this rallying cry, a donation of one thousand rupees was sent forth on behalf of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat, solidifying its commitment. (Annual Report Sadr Anjuman Ahmadiyya, 1911-12, p. 81)

Forging unity – Preserving distinction

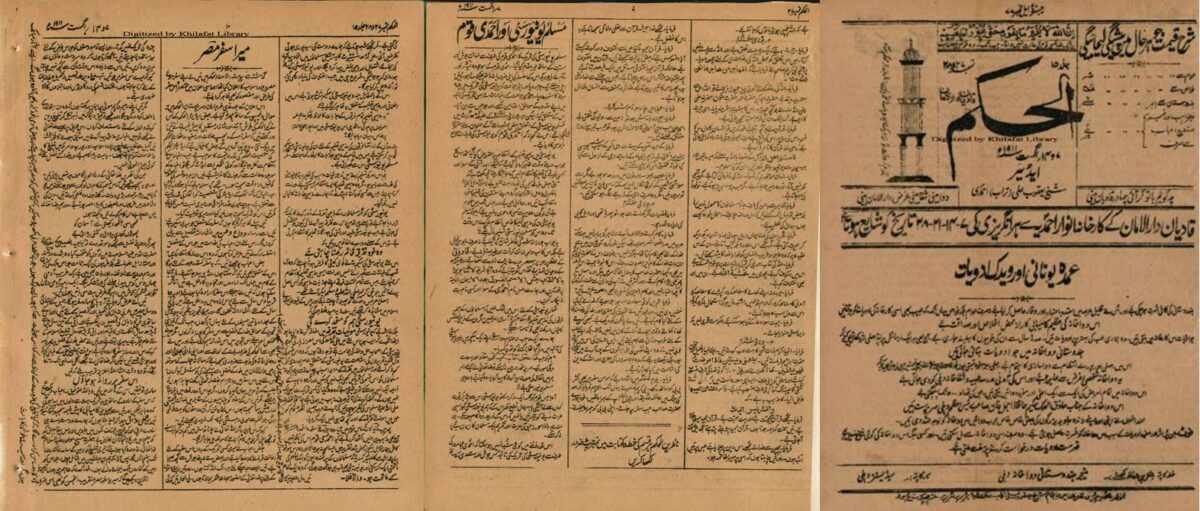

As the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat embraced this rallying cause, a delicate balance emerged – the imperative to foster unity with the broader Muslim community through the university endeavour, while safeguarding their distinct identity. In a profound discourse recorded in the pages of Al Hakam, 7 March 1911, and Badr, 8 March 1911, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Ira elucidated the nuances of this intricate dynamic:

“We have decided upon participation (the manifestation of this decision will happen soon). It is certainly necessary to work together on common matters, but it is also necessary to maintain distinction.”

He expounded upon the rationale behind the need for distinction, emphasising it as the wellspring of progress, the bulwark of honour, the catalyst for moral rectitude, and the forge for striving and prayer. Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Ira underscored the impossibility of complete reconciliation, for such a notion would undermine the very essence of the Ahmadi identity.

These profound words, recorded in the annals of Al Hakam and Badr, echoed a sentiment that would reverberate through the ages – the Ahmadi quest was not merely one of unity, but of preserving the sacred distinction that defined their path to Islamic revival.

Contention over nomenclature amid the university discourse

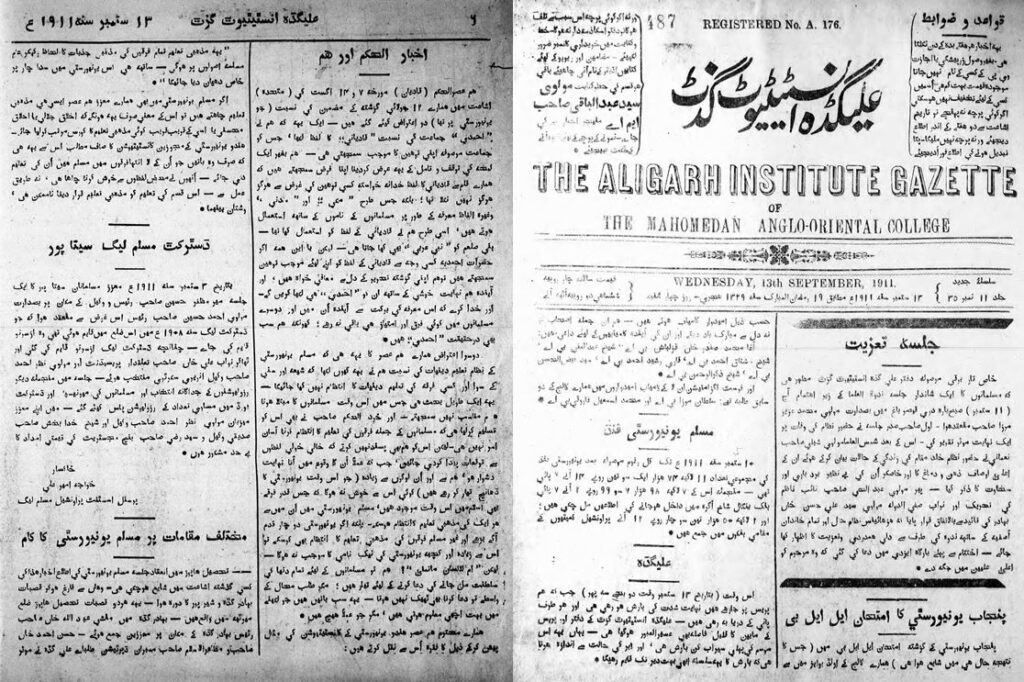

As the Ahmadi involvement in the Muslim University movement gained momentum, a contentious issue arose that struck at the heart of their identity – the very nomenclature by which they were addressed. The Aligarh Institute Gazette, a publication closely associated with the university efforts, referred to the Ahmadis as “Qadianis” in its 12 July 1911 issue while discussing concerns raised by Muhammad Asghar Dehlavi in an article in The Paisa Akhbar’s issue from 10 July 1911 about how the religious teachings of the 72 sects of Islam could possibly be accommodated in the university’s curriculum.

The Ahmadi Muslim newspaper Badr swiftly responded to this affront in its 27 July 1911 issue, invoking the Quranic injunction: “nor call one another by nick-names” (Surah al-Hujurat, Ch.49: V.12). Hazrat Mufti Muhammad Sadiqra, the then editor of Badr, affirmed the true identity as “Ahmadis,” a title derived from the revered figure of the Holy Prophet Muhammadsa, emphasising the unwavering allegiance to the teachings of Islam as revived by the Promised Messiah, Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas.

In this profound exposition amidst the escalating discourse surrounding the Muslim University, Hazrat Mufti Muhammad Sadiqra elucidated the significance of this nomenclature: “We are not Qadianis, we are Ahmadis. […] It is a matter of great regret that when this mistake is made by a respected elder or a party claiming to be civilised in the context of the university movement. […] We have repeatedly announced our beliefs, and it has been declared time and again that we are devoted to Islam and its adherents.”

This contention over nomenclature was not merely a matter of semantics, but a battle for the preservation of the Ahmadi identity – an identity rooted in the revivalist teachings of the Promised Messiahas. It struck at the very heart of their involvement in the Muslim University endeavour, a movement they had wholeheartedly embraced as a means of fostering unity while safeguarding their distinct identity.

A dilution of Ahmadi identity

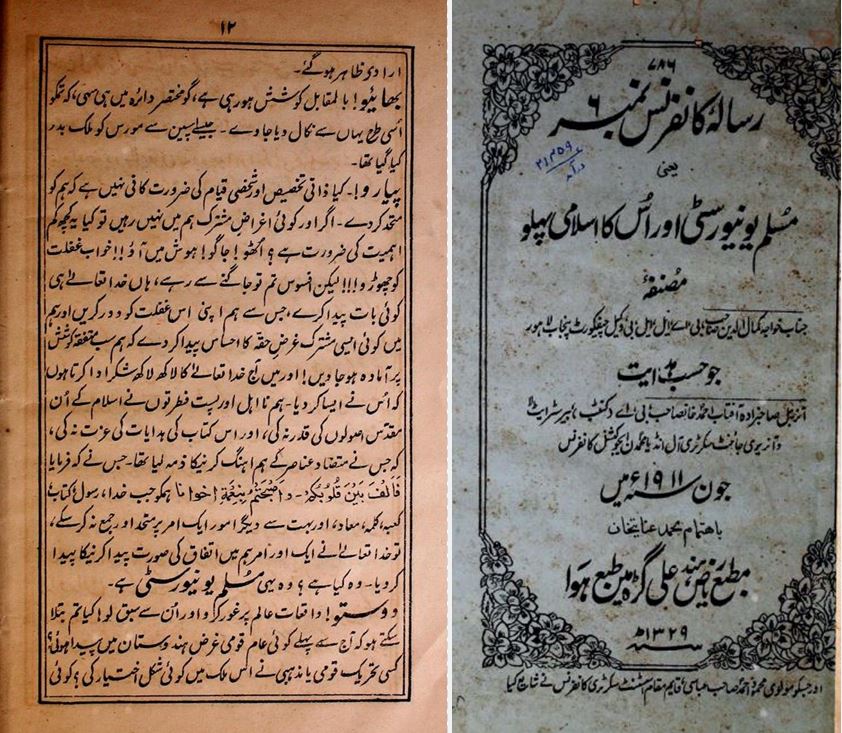

Amidst this discourse, a figure emerged whose approach represented a dilution of Ahmadi identity – Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din Sahib, later a prominent figure within the Lahori Jamaat. In a lecture delivered at Aligarh on 29 June 1911, titled Muslim yunivarsiti aur us ka Islami pehlu (“The Muslim University and its Islamic Aspect”), Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din Sahib echoed sentiments of unity, but his rhetoric compromised the distinct teachings of the Promised Messiahas.

“If God, the Prophet, the Book, the Kaaba, the kalima [Islamic creed], the Hereafter, and many other matters could not unite us on one matter, then God Almighty has created another opportunity for unity among us. What is it? It is this Muslim University,” he proclaimed, underscoring the university’s potential as a unifying force.

However, Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din Sahib’s approach diluted the essence of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat’s identity, favouring popularity among non-Ahmadi Muslims over the explicit acknowledgement of the Promised Messiah’sas mission. Hazrat Sheikh Yaqub Ali Irfanira, a prominent voice within the Jamaat, exposed this dilution in the pages of the combined issue of Al Hakam of 7 and 14 August 1911:

“The lecturer [referring to Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din Sahib without explicitly naming him] seems to be so engrossed in his own rhetoric that he fails to seize the opportunity to remind the audience that true unity can only be achieved under the guidance of one Imam,” he deplored. “If only he had said that the scattered segments of Muslims can only be united under the leadership of one Imam, and that the university’s true significance would lie in its submission to that one Imam.”

Hazrat Sheikh Yaqub Ali Irfani’sra critique laid bare the stark reality – that Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din Sahib’s quest for acceptance and acclaim among the broader Muslim community came at the cost of diluting the Ahmadi identity and the pivotal role of the Promised Messiahas in reviving the true spirit of Islam.

Irreconcilable divergences

As the discourse surrounding the Muslim University raged on, Hazrat Sheikh Yaqub Ali Irfanira, who had previously chronicled Hazrat Khalifatul Masih I’sra profound discourse on unity and distinction, levelled a scathing critique against the Aligarh Institute Gazette’s stance in that same combined issue of Al Hakam of 7 and 14 August 1911. The Gazette had stated that while Sunni and Shia instruction would be organised by the Muslim University, “groups of small numbers” like Ahmadis would manage their own religious education. He exposed what he perceived as the crux of the matter – the Muslims’ inability and unwillingness to embrace the Ahmadis as equal partners in the pursuit of Islamic revival.

“The [Aligarh Institute] Gazette’s article has given the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat little cause for optimism regarding the university’s ability to foster true unity,” the esteemed editor lamented. “By explicitly stating that religious education will only cater to Sunni and Shia sects, while relegating ‘groups of small numbers’ like the Ahmadis to manage their own religious instruction, the university has effectively sown the seeds of further division.”

His critique, echoing the very words he had recorded from Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Ira, struck at the heart of the Ahmadiyya quest – a pursuit of unity that did not compromise their distinct identity as revivalists of Islam under the guidance of the Promised Messiahra. “If the university truly seeks to unite the scattered segments of the Muslim Ummah, should it not embrace the very group that has arisen to revive the true spirit of Islam?” he questioned rhetorically.

The Aligarh Institute Gazette’s response, published in its 13 September 1911 issue, sought to clarify its stance and acknowledge the inadvertent offense caused by the use of the term “Qadiani.” However, this conciliatory gesture did little to assuage the deeper concerns that had been raised.

A timeless legacy of perseverance

As the sun set on this historic discourse, the echoes of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat’s pursuit reverberate through the annals of Islamic renaissance. The unwavering dedication to upholding the true spirit of Islam, as embodied in the teachings of the Promised Messiahas, while preserving the distinct identity as Ahmadis, resonates through the ages, serving as a testament to the enduring power of faith, reason, and perseverance.

In the face of resistance and rejection from the broader Muslim community, the Jamaat’s steadfastness stands as a shining example of how even the most daunting challenges can be navigated with wisdom, compassion, and an unwavering commitment to the principles of Islam as revived by the Promised Messiahas.

As the world continues to grapple with the complexities of religious pluralism and coexistence, the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat’s legacy stands as a timeless reminder of the delicate balance between preserving one’s distinct identity and fostering unity within the wider community of faith. The pursuit, forged in the crucible of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, remains as relevant today as it was then – a journey towards harmony that honours the revivalist teachings of the Promised Messiahas, a quest for unity that does not compromise the sacred distinction that defines the path.