The Review of Religions [English], January & February 1922

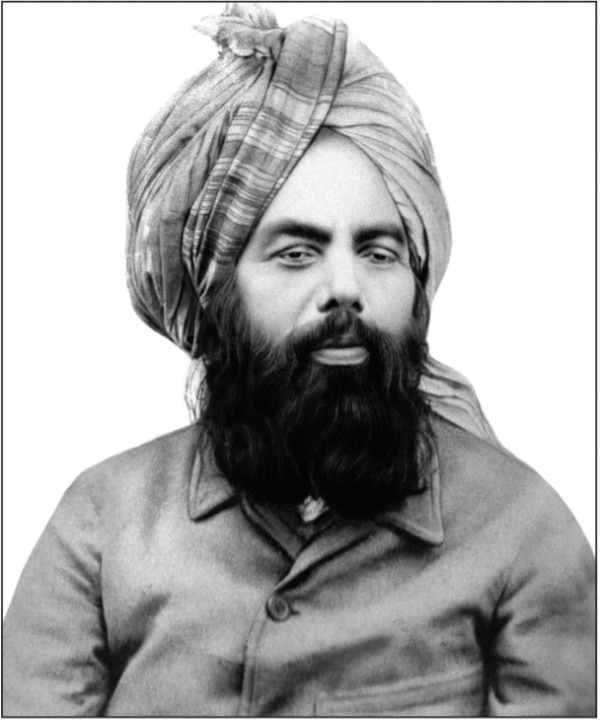

An anecdote from the early life of the Promised Messiah[as] as related by an old Hindu. [Editor, The Review of Religions (1922)]

From his very childhood he was given to retirement and seclusion. He would not take part in the boyish games. His whole life from the very dawn of boyhood up to his youth and manhood was one continuous chain of virtuous and pious acts. He would never utter an abusive epithet, he did not call any one names, he would not practise the pranks which the youth are so fond of, and he would never tell a lie or kick up a row. We regarded him as a simple, indolent and slothful companion who had no heart in the boyish games for which we evinced so much zest. We had our boyish anxieties whether he should ever make a home at all, for we knew that he loved his secluded and lonely closet wherein he would remain confined for days together. Though he would sometimes come out with us but he ever remained a stranger. He was never on terms of familiarity with anyone. He never spoke any harsh or offensive word to anyone. There was no friendly give and take as with the common run of boyhood. His was a strange sort of pure life. He would never call at any boy’s house, nor would they at his. As a matter of fact, there was no free-mixing at all. He did not know what was going on about him or how the world was faring. Whenever we drew his attention to this sleepiness in his character, he would only smile and be silent. Rustics as we were, we used to admonish him sometimes in our own boyish way.

His father, Mirza Ghulam Murtaza, would very often depute one of us to fetch him. He, of course, would filially and dutifully obey his father’s behest. He would immediately put in his appearance before his father and quietly take his seat. All the time he would sit, he would never look up; like a bashful maiden, he ever kept his looks down, and his father would impress upon him the necessity of his looking about his worldly affairs. He would generally begin in this way: “Ghulam Ahmad, my son, I am ever anxious about you. I do not know how you shall make your living. How long would you go on like that? You must take up some profession to earn your livelihood. How long would you spend away your time like a new bride? Something must be done to earn one’s living. Look here. The world earns and spends. People do their daily toils. Some day you will be married and make a home. Your wife and children will look to you for their food and clothing and other necessities of life. You will have to be responsible for their upkeep. Your present condition is not a hopeful augury for the future. I shudder to think of marrying you. Look up my son. Shake off this lethargy and indolent simplicity. Do you think I shall live forever and look to your maintenance? I am well known to a good many English officials. They have a deep regard for me. I [will] give you a letter of introduction; gird up your loins. If you like, I can personally interview the English officials on your behalf and see [what] they can do for you.” But Mirza Ghulam Ahmad would keep dead silent all the while his father effused on account of paternal regard and solicitude for his beloved son. Such scenes were frequently enacted before our eyes. All he had to say to his father’s repeated requests was: “Father, let me know whether one who is the servant of the Ruler of the Rulers, should care a bit for these worldly services. All the same, father, you will always find me amenable to the least of your wishes.” Hearing this, his father would allow him to go back to his closet.

Once after such an interview as the one described above, Mirza Ghulam Murtaza turned to us and said that Ghulam Ahmad his son would ever remain the hermit that he was. In his opinion, his son was not fit to become even the village priest whereby he could hope to earn his livelihood by getting tithes in kind. He would express his deep anxiety for his future when he was gone from him, or he said that his son was too good to suit the times. Then, tears would well up in his eyes while he would say, “What he (Ghulam Ahmad) is we cannot be. He is not earthly; he is a heavenly being. He is an angel, not a mortal.”

At this, the eyes of that old Hindu narrator of this episode would become tear dimmed, and he would point to the religious activity of which Ghulam Ahmad[as] is the centre and nucleus. He would sigh for the presence of the Promised Messiah’s[as] father who would have been wonder struck to find this progress and activity and the worldwide fame of his son.

(Transcribed by Al Hakam from the original in The Review of Religions [English], January and February 1922)