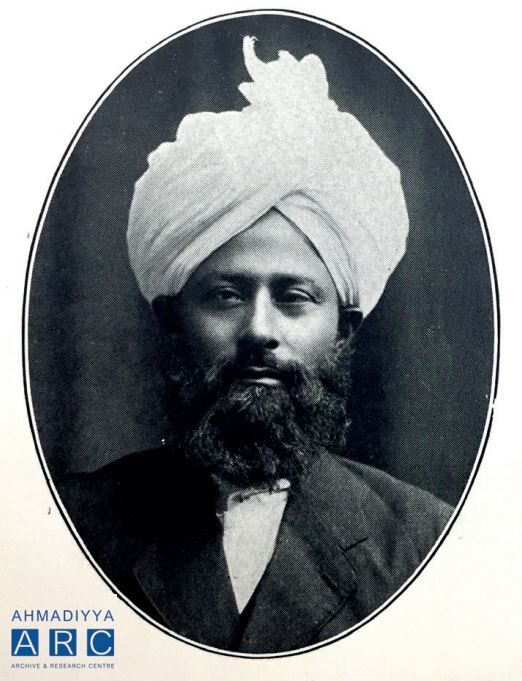

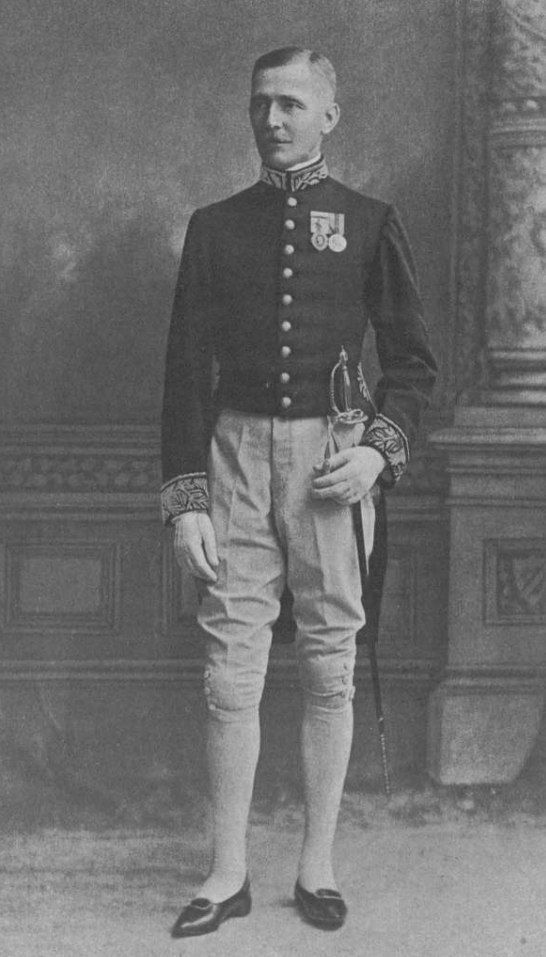

On 13 November 1923, His Holiness, the [then] Head of the Ahmadiyya Community, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih II[ra] had an interview with His Excellency, Sir Edward Maclagan Governor of the Punjab. His Holiness had a long talk with His Excellency about the present political condition of the country and laid certain practical suggestions before the latter calculated to establish peace and prevent unrest in the country. At the end of the interview, His Excellency, the Governor desired that a summary of these suggestions be submitted to him in writing. This summary which has already been submitted to the Governor we insert below for the benefit of our readers. […] – Editor, The Review of Religions (1923)

Between the Hindus and Muslims there exists nowadays great hatred and discord and this is of two kinds: (a) Political; and (b) Religious.

Seeing this hatred and discord, the Muslims have begun to realise that they stand in need of some helper to maintain their existence.

But in spite of this feeling, they do not turn to the government for they think, (whether erroneously or on the basis of certain grounds), that the government does not sympathise with them in their troubles and gives the Hindus preference over them.

So, I beg to lay before the government the following proposals which are calculated not only to remove religious and political unrest but also to strengthen the power of the government and conciliate the Muslims. The government should adopt the following course in order to establish political peace and conciliate the Muslims:

The suspicion of the Muslims that the government favours the Hindus may be dispelled by a declaration on the part of His Excellency, the Viceroy on some public occasion to the effect that such suspicions are utterly devoid of foundation, that the government has an equal regard for all its subjects and that it is ever ready to help the wronged and the oppressed no matter to what nationality or religion they may belong.

The Muslims should have given to them their legitimate rights. Nowadays they are not adequately represented in the Colleges, (particularly the technical institutions), in the University, in the Services and in the Local Self-government, their representations in all these lines being quite out of proportion to their numbers. This question has engaged the attention of the government for some time past, but there is still much room for improvement. The doors of education being practically closed to the agriculturists, they are suffering badly froma lack of education. They turned their attention to education very late and now finding its doors closed against them, they are extremely discontented and disappointed.

As regards the present Hindu-Muslim disputes, the government should adopt the following course. Its representatives should first hear the grievances of the Muslims through their representatives and then those of the Hindus through the representatives of the Hindu Community and then, by calling a meeting of both Hindu and Muslim representatives, should try to bring about reconciliation between the two communities.

In order to remove religious unrest, the following course may, in my opinion, be followed with advantage:

The law relating to intervention on the part of the government in religious matters should be made more clear and definite. Until now this law has not been perfectly clear even to the authorities, for it has been differently applied by different authorities. I think the proper course will be to separate the offence of creating religious hatred from that of creating hatred against the government and the law relating to the offence of creating religious hatred should be modified by further restrictions. One result of the law being undefined is that many men who are guilty of creating serious agitation go scot-free while some who honestly try not to trespass the bounds of the law fall victims to it.

It has been observed that the government sometimes does not put this law in force for a time and then all of a sudden it begins to bring the law into operation. This causes much dissatisfaction. I think it would be well if the government should on such occasions issue a communique, warning the public, before bringing the law into strict operation and should take action only against such persons as do not refrain even after the general warning.

Before taking action against any person, the government should take into consideration the following facts:

Firstly, the government should see whether the writer or the speaker whose case is under consideration is the first to write or speak in the matter or is only replying to any writing or speech of another which, in spite of being inflammatory, escaped the notice of the government and in case of its being a writing, was not confiscated by the government.

Secondly, the government should see whether the person who replies to a writing or speech confines himself only to the reply and does not introduce any new subject of an offensive matter.

If such be the circumstances, then the government should not take any action against the person concerned. The reason is that it is the government which can take any action against those who offend against this law and no other party can sue the offender. Consequently, it is necessary to take into consideration the fact that the person concerned was led to write that book or make that speech because he saw that the government had taken no action against the man who had originally trespassed the bounds of law while attacking his religion.

Not only the author of an offensive work should be taken action against but even the book itself should be confiscated.

There should be co-operation between the different provinces. Nowadays, while in one province extremely inflammatory writings are freely published without let or hindrance, in another province action is taken against far less inflammatory writings, although mischief is caused not by the locality of the printing press but by the perusal of books and papers. This also gives rise to much discontent.

If it be impossible to secure the co-operation of different provinces, at least this much can be done that, when necessary, the provincial governments should not only take action against the writers of their own provinces but should prohibit the publication in their respective provinces even of such literature as is printed in other provinces and contains inflammatory matter so that real purpose may be gained in this way.

As the offence in the case of religious literature is not political but is due to the misapplication of religious controversy, the offender should be pardoned on his making an apology and on his writing being confiscated.

Besides punitive measures, preventive steps should also be taken to improve the tone of religious literature and for this purpose, I beg to make the following suggestions:

In the first place, it should be enacted that no person shall criticise other religious systems but shall confine himself to an exposition of the beauties of his own religion.

Failing this the present law must be modified in so far as to render unlawful the making of an attack on another religion which can with equal force be directed against one’s own religion; for to criticise such principles as one holds in common with the followers of another religion only shows that the object of the critic is no other than to inflame others and excite hatred and ridicule.

If the government find itself unable to see its way to the acceptance of this proposal also, it should, after consulting the followers of various religions, draw up a list of such books as are believed to be authentic by the adherents of different creeds and should lay it down that no one shall base his criticism of any religion on any books other than those included in the list of authentic books of that religion. This step is also calculated to put an end to a good deal of religious contention, for much of the present excitement and rancour in religious controversy is due to the fact that criticism is based not on the books recognised as authentic by the followers of different religions but on legendary tales and inauthentic writings and traditions.

Though these matters of law do not lie within the province of the local government, yet they can move the central government for legislation on these matters.

These suggestions, if followed, will, I hope, tend to strengthen the government, establish peace and prevent unrest and agitation in the future.

(Transcribed and edited by Al Hakam from the original, published in The Review of Religions [English], November and December 1923)