7 September 1974 was a day celebrated by the clerics and the right-wing politicians of Pakistan as a victory of “Islam” against Ahmadiyyat; the day when the infamous declaration of Pakistan’s national assembly came out declaring Ahmadis as a non-Muslim minority.

This did not just happen overnight. This declaration of heresy took two decades of jealousy. Ahmadiyya literature is full of explanations of what went on and what it took for the Pakistani legislative body to intervene in purely theological differences; what it was that united the extremely disunited clergy against the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat. Today, we would like to present the viewpoint of a neutral, fair-minded historian and political analyst to see how they trace the roots of this infamous, inhumane declaration of the Pakistani government.

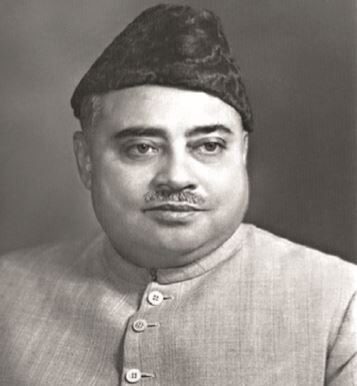

The following are extracts from Husain Haqqani’s book Reimagining Pakistan.

Al Hakam is thankful to Mr Husain Haqqani for granting permission to include these extracts:

Husain Haqqani, USA

A major manifestation of the pitfalls of religion-based politics came in January 1953, when clerics of various Muslim denominations demanded that the Ahmadi sect be declared non-Muslim for legal purposes. Widespread riots soon followed, resulting in dozens of deaths and considerable loss to property. Reflecting what has been a consistent pattern in Pakistan’s history, the religious demand also had a worldly purpose. Punjabi politicians had instigated the clerics in the hope of dislodging the government of Bengali prime minister, Khawaja Nazimuddin, who had taken office after Liaquat’s assassination two years earlier.

Nazimuddin turned down an ultimatum from the ulema to declare members of the Ahmadi sect as a non-Muslim minority and to dismiss Foreign Minister Chaudhri Zafrullah Khan, who was an Ahmadi. The ulema also demanded that other Ahmadis occupying key posts in the state must also be removed from their offices. Punjab chief minister Mumtaz Daultana had activated the protestors in the hope of bringing down the federal government and becoming prime minister …

Nazimuddin’s decision to refuse the ulema’s demands had wide support at the time across the government and Pakistani society. The Ahmadi issue was limited to Punjab as that is where the sect had its principal following. Non-Punjabi polilticians did not associate themselves with the clerics or the Punjabi politicians supporting them. Pakistan’s secular leadership succeeded in pushing back a religious demand and the army enforced order, putting the Islamists and their rioting followers in their place …

At that time, the government set up a commission of inquiry, headed by the chief justice of the Lahore High Court, Muhammad Munir (who went on to become chief justice of Pakistan), to look into the causes of the anti-Ahmadi disturbances. In 117 sittings, the commission examined 3,600 pages of written statements and 2,700 pages of evidence. It went through 399 documents …

Its conclusion was that heeding the demands of the theologians in matters of state was a slippery slope and that Pakistan would do well to avoid it.

The 387-page report of the Munir Commission reflects the thinking of Pakistan’s ruling elite in the country’s early years. The report scrutinized “with the assistance of the ulema” their “conception of an Islamic State and its implications” and declared, “No one who has given serious thought to the introduction of a religious State in Pakistan has failed to notice the tremendous difficulties with which any such scheme must be confronted.”

“The Quaid-i-Azam said that the new State would be a modern democratic State,” it continued, adding that Jinnah’s concept of Pakistan required that sovereignty must be vested in the people and “the members of the new nation” should have “equal rights of citizenship regardless of their religion, caste or creed” …

The most important statement of the Commission, however, related to the differences among the clerics, which would divide Pakistanis more that religion could unite them. “The ulema were divided in their opinions when they were asked to cite some precedent of an Islamic State in Muslim history,” Justice Munir reported, pointing out that “no two learned divines are agreed” even on the fundamental definition of who is a Muslim.

In Justice Munir’s words, the anti-Ahmadi riots demonstrated that if “you can persuade the masses to believe that something they are asked to do is religiously right or enjoined by religion, you can set them to any course of action regardless of all considerations of discipline, loyalty, decency, morality or civic sense”. Munir warned that Pakistan was “being taken by the common man” as an Islamic State. In his view, this belief had been encouraged “by the ceaseless clamour for Islam and Islamic State that is being heard from all quarters since the establishment of Pakistan”. In words that were not heeded, the chief justice cautioned against letting the “phantom of an Islamic State” haunt the new country.

Notwithstanding Munir’s warnings … religious exhortations continued to consume the nation’s energies.

Under Bhutto, Pakistan still juggled between the needs of a modern state and pressure from clerics to recreate a bygone era … Bhutto portrayed himself, in the words of political scientist Anwar Syed, as “a Socialist Servant of Islam”. To rebut the argument of his Islamist opponents that socialism was “antithetical to God and religion”, Bhutto “advertised his personal dedication to Islam” and “insisted that he was a good Muslim”. He said, “he was proud of being a Muslim; indeed, he was first a Muslim and then a Pakistani” …

The first major manifestation of that inclination in constitutional and legal terms occurred when Islamist groups rioted against the Ahmadi sect. The riots began after a clash in May between Islamist and Ahmadi students at the Railway station of Rabwah, the town where the Ahmadi sect has its headquarters.

Islamist demands against the Ahmadis were no different this time around than they had been almost two decades earlier. But in 1953, Prime Minister Nazimuddin had been willing to call in the army to stop the rioters and Justice Munir had written his report pointing out the problem with the state accepting demands to define which sect was or was not Islamic. Now, Bhutto was unwilling to follow in Nazimuddin’s footsteps and there was no one of Munir’s stature to remind the government that it should not allow clerics to dictate legislation.

Even though the Ahmadis had, as a community, backed Bhutto in the 1970 election, Bhutto decided to join the religious parties he had defeated at the polls in amending Pakistan’s constitution (framed only a year earlier) to define ‘Muslim’ in a way that specifically excluded Ahmadis from the fold of Islam. The Islamists got their biggest legislative victory since the Objectives Resolution and that too after losing a general election …

In 1974, the political leadership sought political advantage by appeasing clerics making anti-Ahmadi demands. Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto declared it an “achievement” that he secured support of all major political parties in amending the constitution to declare Ahmadis non-Muslim under law. A few years later, military ruler Zia legislated restrictions on Ahmadi professions of faith, making it a punishable offence for an Ahmadi to act in a manner that made him or her seem to be a Muslim. The judiciary upheld Zia’s laws on grounds that by acting like a Muslim or using nomenclature used by Muslims, an Ahmadi offended Muslims and, therefore, deserved the punishment prescribed by Zia.

Had Bhutto, Zia and the judges acted like Pakistan’s leaders did in 1953, Pakistan could have avoided being saddled with a constitutional amendment and laws that are deemed by the rest of the world as violating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

I could not resist commenting. Very well written!

I really like the standpoint!