Asif M Basit, Ahmadiyya Archive and Research Centre

Today, we take our readers a century back in time – well, 95 years to be precise.

It was 1925 and the issue of blasphemy had not yet turned into a selling point for religious extremists. Even back then, Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya would protest against any act that compromised the honour of the Prophet of Islam. This protest – peaceful yet powerful – would be acknowledged and would bear fruits by culprits expressing their regret in response.

England has always been known for its world-leading performance in cricket. The year 1925 had seen great anticipation in cricket aficionados that Jack Hobbs – England’s top-ranking first-class cricketer – set a new record.

Living up to the expectations of his fans, Hobbs scored his 126th century as his team played against Somerset. As this broke the long-standing record of 125 centuries by Grace – another English cricketer – the whole country went into a frenzy of celebration; newspapers leading the much-exaggerated fuss from the front.

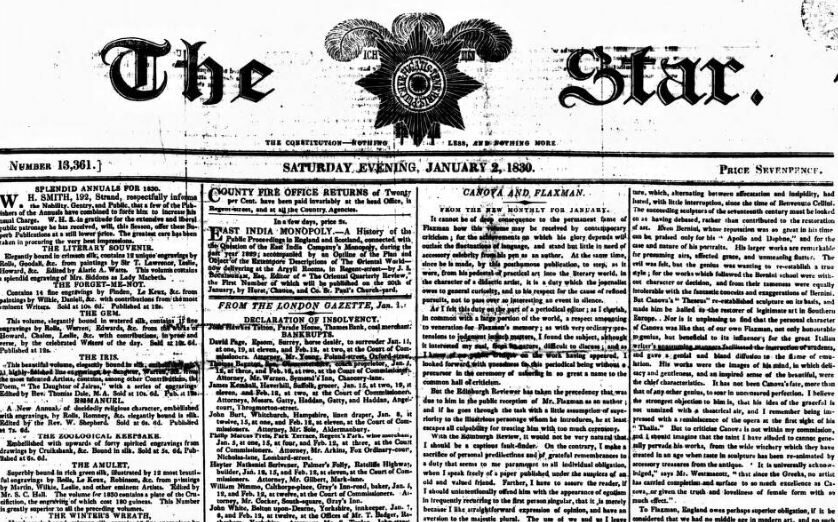

In its issue of 18 August 1925, The Star – a London based evening daily – printed a cartoon by David Low which depicted “a gallery of the most important historical celebrities”. All celebrities, standing on pedestals, were shown gazing up, as if in envy, at the tall and towering figure of Jack Hobbs who – holding his head high in pride – stood in the middle.

Amongst the celebrities, Prophet Adamas and the Holy Prophetsa of Islam were also depicted.

Adding insult to injury, a long sword was shown hanging from the waist of the Holy Prophetsa of Islam. Adamas was depicted as an almost-nude figure, more similar to a chimpanzee than a human.

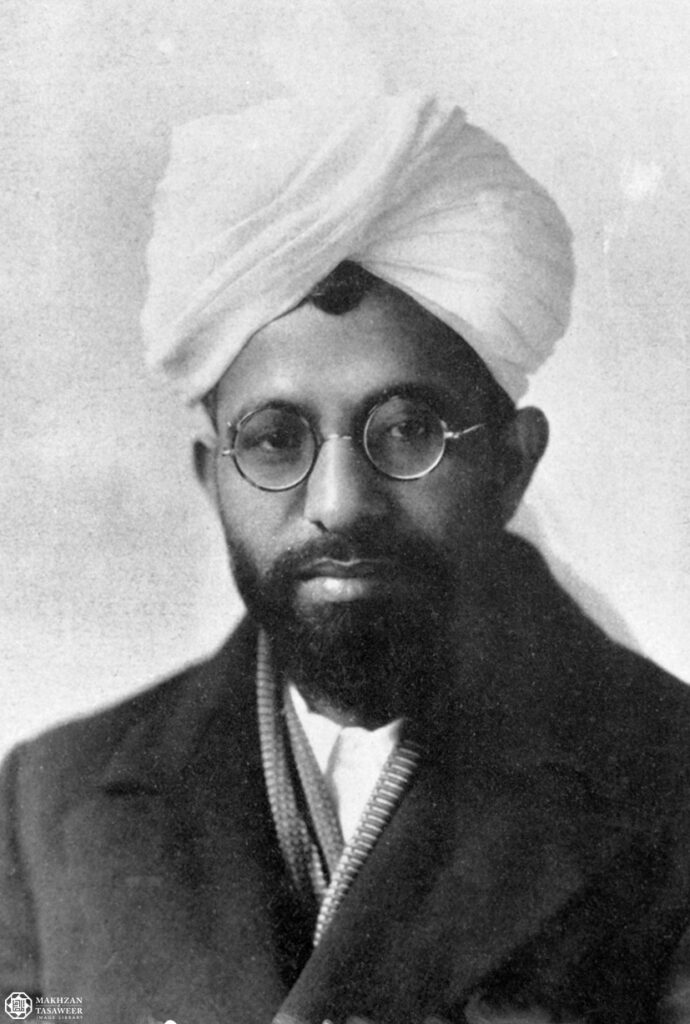

As soon as the cartoon appeared, AR Dard – then imam of the London Mosque and missionary of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in England – took immediate notice and wrote letters not only to the editor of The Star, but also to the home secretary to express the injury it had caused to the sentiments of Muslims. He went on to send copies of these letters to other newspapers in England.

The letter addressed to the home secretary read:

“Your Excellency,

“In my capacity as the head of a very big section of the Muslim community in England, I deem it necessary to convey to Your Excellency on their behalf, and on behalf of many Egyptian, Indian and African Muslims who have approached me for that purpose, the feelings of fierce indignation and deep mortification that a cartoon printed in ‘The Star’, dated 18/8/25 (of which a copy is attached herewith) has aroused.

“The cartoon depicts Mr. Jack Hobbs as a colossal figure. At his feet are shown to stand some very reputed historical personages, including among them Adam and Mohammad the Holy Prophet of Islam (may peace and blessings of God be upon him). Like all others, they are made to look at Mr Hobbs apparently in astonishment and bewilderment at the latter scoring so many centuries in cricket. This ignominiously disgraceful cartoon has inflicted a deep wound on the religious susceptibilities of the Muslims.

“The Holy Prophet Mohammad (peace and blessings of God be upon him) is the most sacred personage for the Muslims. The love they bear towards him and the veneration with which they cherish his holy memory transcends all barriers of colour, caste and country. Of all earthly things, the most revered in their eyes is the honour of their Spiritual Master for whose sake every Muslim, young or old, high or low, man or woman, is ready to sacrifice his life and his all. A Muslim can bear anything but an affront offered to the name of his beloved and revered Master. Your Excellency can, therefore, only imagine the intensity and the depth of the feelings that this manifold insult has stirred. Words cannot adequately express it. The greatest Monarch, of unequalled spiritual glory, the most perfect manifestation of God, the Cynosure of all eyes, the Prince of Peace, and a Mercy unto all mankind painted as a pigmy lost in amazement, and as a monster of bloodshed and carnage with a drawn sword in his hand! No art could degenerate so low. Nothing could be more mischievous, on the part of a paper, than to play with the religious susceptibilities of a people. It is a disgrace to journalism. Could not the admiration of a cricketer be complete without heaping unmerited and unprovoked disgraces on the name of one who takes his stand in the first row of the greatest reformers of humanity? Surely this is the most malicious and insidious form of comparison.

“I need not draw Your Excellency’s attention to the storm of indignation and hatred which this cartoon would raise in India and all other Muslim countries.

“I protest, therefore, most empathically, against this despicable indignity loaded on our Holy Prophet (may peace and blessings of God be upon him) and request Your Excellency to give your most earnest attention to this very serious matter and set the law in motion against the offenders, so that the world may know that England is justly proud of her traditional fairness ad impartiality.

“Your Excellency’s most obedient servant,

“AR Dard, MA, The Imam

London, 26/8/25” (The Review of Religions, November 1925)

This letter of protest was picked up by the press and created a stir in the English society, more so in the government circles.

The Herald, in its issue of 1 September 1925, covered the controversy with the headline:

“Muslim Feelings Injured: Set Law in Motion”

The details read as follows:

“The Home Secretary has received from the head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Mission in London a protest, on behalf of the Muslim community in England, against the publication of a cartoon which appeared in The Star, London, when Hobbs surpassed the record of cricket centuries made by the late WG Grace”.

Then followed the details of what the cartoon depicted and excerpts from AR Dard’s letter that informed the home secretary about the status that the Holy Prophet of Islam holds in every Muslim heart.

“The writer asks, in conclusion”, the news went on, “that the Home Secretary shall ‘set the law in motion’ against the offenders, so that the world may know that England is justly proud of her traditional fairness and impartiality”. (The Daily Herald, 1 September 1925)

Reporting on this issue, Al Fazl Qadian commented:

“We would like to call the attention of the Government of India to this tragic issue so that it can represent the sentiments of its Muslim subjects before His Majesty the King-Emperor […]”. (Al Fazl Qadian, 26 September 1925)

The line of action given to AR Dard by the headquarters in Qadian can be summed up in the following report of Al Fazl:

“While such letters [written by AR Dard] have helped shaming the The Star, they must have helped bring to public knowledge the level of respect and reverence that Muslims hold for the Holy Prophet of Islam. This is indeed important for had the Europeans not been so unaware, they would not injure the religious sentiments of Muslims so boldly. It is incumbent upon Muslim missionaries that they replace this unawareness with an understanding of Islamic beliefs.” (Al Fazl, 29 September 1925)

This peaceful protest of the Ahmadiyya mission in London generated a similar response from other Muslim circles.

Al-Ahram, Cairo – an esteemed newspaper of the Muslim world – published communiqués received through their London correspondent about the Ahmadiyya response to the cartoon. AR Dard’s letter was published in full in the Al-Ahram issue of 4 September 1925.

The Al-Azhar University, the much-esteemed academic institute for the Egyptians and other Muslims alike, published their appeal to the king of Egypt. The English translation of Al-Azhar’s appeal as published in Al-Ahram is as follows:

“We published yesterday a telegram received by al-Ahram’s London correspondent. He mentions a protest written to the home secretary by an honoured member of the Ahmadiyya community in London. The letter is regarding the casual cartoon published in The Star newspaper, depicting prophets and other renowned persons. We received this letter in our recent post, the translation of which is as follows…”

Next, the Ahmadiyya protest letter was published in full.

Following the letter was an appeal by the scholars from Al-Azhar to the king of Egypt:

“We shall take great part in standing up against the lack of respect displayed towards the very being and attributes of the Holy Prophet and will support the dismay expressed towards The Star by the Muslims.”

Also, “we shall demand on behalf of all Muslims, that the press should always regard the limits set by Allah in regard to His prophets.”

This editorial piece was followed by the Ahmadiyya letter and signed by 22 scholars of al-Azhar University.

Praise of the Ahmadiyya protest in the Muslim world

This episode of history bears witness to the fact that whenever the Western world of journalism disregarded religious values in the name of freedom of speech, the Ahmadiyya Muslim community has led from the front in protest. Other Muslim sects would also agree with the Ahmadiyya approach of protest, which was, and is the best approach.

The news of this cartoon and the Ahmadiyya protest reached the Muslims of the subcontinent as well.

Zamindar, a newspaper owned and edited by Zafar Ali Khan, had always maintained a stringent anti-Ahmadiyya approach. But on this occasion, Zamindar too was compelled to state:

“Muslims should be grateful to Maulvi Abdul Rahim Dard MA, Imam of the Ahmadiyya mosque, Putney. His immediate and powerful response to the home secretary, protesting this shameless cartoon, has thoroughly conveyed the anger and fury felt by Muslims all over the world.”

Similarly, the 22 September 1925 issue of Al-Jamiat, the newspaper of Jamiat-e-Ulama-e-Hind, wrote:

“The readiness displayed by the Ahmadiyya community whilst advocating for the Muslims against this seditious cartoon is praiseworthy.”

It also commended the Ahmadiyya protest letter to have “done justice to representing the Muslims of Britain, India, Egypt and Africa.”

Since the spite and malice against the Ahmadiyya community was, nevertheless, intense, Al-Jamiat did not fail to maintain that undercurrent by quoting the Hadith:

انّ اللہ یؤیّدالدین برجُل فاجر

They gave no translation as it was simply added to register that this appreciation did not mean friendship with Ahmadis. Otherwise, the general Muslim public – mostly unacquainted with Arabic – would have seen it as below the belt.

The majority of the Indian press praised the Ahmadiyya Community for upholding the honour of the Holy Prophetsa.

The 15 September issue of Hamdard newspaper, owned by Maulana Muhammad Ali Johar, commented:

“The Ahmadiyya community in London has brought this cartoon to the attention of the home secretary. They have demanded legal action against the newspaper for this unethical and derogatory publication. The community has also laid forth, in its letter, the hurt and injury it would cause to the Muslims of the Indian subcontinent or other Muslim nations if the cartoon was to reach them.”

The 17 September edition of Hamdum, an esteemed newspaper of the United Provinces, wrote:

“It brings us great satisfaction to know what Mr AR Dard MA, in charge of the Ahmadiyya mission in Britain and Imam of their London mosque, has done. He has, in a request to the home secretary, highlighted the audaciousness of The Star newspaper and demanded legal action.”

Another popular newspaper Siyasat, Lahore, covered the story with the same level of appreciation.

The strong protest made by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat did not go in vain. The impact was to be witnessed very soon.

Wilson Pope, the editor of The Star, wrote a reply to Hazrat Maulana Abdur Rahim Dard’sra protest letter on the 3 September:

“The home secretary has sent me a copy of the protest letter regarding cartoons published in The Star on 18 and 26 August. Let me start by saying that the government has no right to interfere in this matter.

“Let me also say that had we known that this cartoon would deeply wound the religious sentiments of Muslims, we would never have published it. I assure you that this cartoon was never, by any means, intended to hurt the Muslims. I am greatly saddened by the hurt it has caused to your co-religionists.”

The Imam of Masjid Fazal London also received a reply from Jack Hobbs:

“Surrey County Cricket Club

“Kennington Oval, S.E. 11

“29/8/1925

“Dear Sir,

“I am pained to know that the cartoon in The Star dated 18/8/25 has offended the feelings of all Muslims.

“I need not say that I have no control over The Star nor any responsibility for the cartoons which it publishes. I am, however, pleased to learn that The Star has published its regrets and that it, and its cartoonists, would have refrained from introducing the figure of Mohammed (peace be upon him) if they had thought it could give offence.

“I am sorry that my success in cricket which has been shared with me by sport-loving people all over the world has thus, unfortunately, become the occasion of wounding the religious susceptibility of my Muslim friends.”

“I wish it had not been so.”

“Believe me,

Yours sincerely,

(Signed) JB Hobbs.”

Hazrat Maulana Abdul Rahim Dardra immediately wrote back to Hobbs. After expressing his gratitude for the letter, Dard Sahibra wrote:

“I am not at all holding you responsible over the improper actions of The Star. I am simply requesting you to publicly distance yourself from the cartoon depicted in The Star […]

“I do not disagree with the fact that you don’t hold any responsibility in regards to The Star. However, I honestly believe that even one word opposed to the cartoon would thoroughly suffice in preserving your legacy from any ill manner.

“I believe you will be praised by the Muslim world for distancing yourself and in doing so heal their hearts.

“Yours sincerely,

“AR Dard

“3/9/1925”

Soon after, The Star published its apology to the public followed by Jack Hobb’s aforementioned letter.

The press was excited by the strong protest demonstrated by the Ahmadiyya Jamaat, as were the government circles. Hence, the foreign minister wrote a letter to the Imam of Fazl mosque:

“I have been instructed by Foreign Secretary, Lord Chamberlain, to acknowledge your letter of 27 August. This letter (which you also sent a copy of) was a protest regarding the cartoon published in The Star on the 18th of August and was addressed to the foreign secretary.

“I want to inform you that the government is unable to take any legal action against the newspaper. Nevertheless, Lord Chamberlain took it upon himself to discuss your widely renowned protest in person with the editor of The Star. This informal meeting led to the editor of the newspaper publishing his apology on the 9th of September. A copy of the apology is hereby attached for you. I hope that this should satisfy the community.”

The outcome of the protest

The tremendous efforts, displayed by the Ahmadiyya Community, in regard to its protest against the cartoon, had a deep impact on society in general.

This cartoon, appearing in The Star in 1925, was to work as a prelude for the modern-day press creating caricatures of the Holy Prophetsa. Thus, the Ahmadiyya response – by way of a very peaceful yet powerful protest – is recorded in history as the first and best response shown; one that brought back apologies.

We have already seen the apology by the newspaper’s editor, Wilson Pope, which he wrote to the Ahmadiyya mission in London and later published it in the same newspaper. We have also seen that the government, albeit on an informal level, did take action by reminding the editor of the newspaper of his ethical duties.

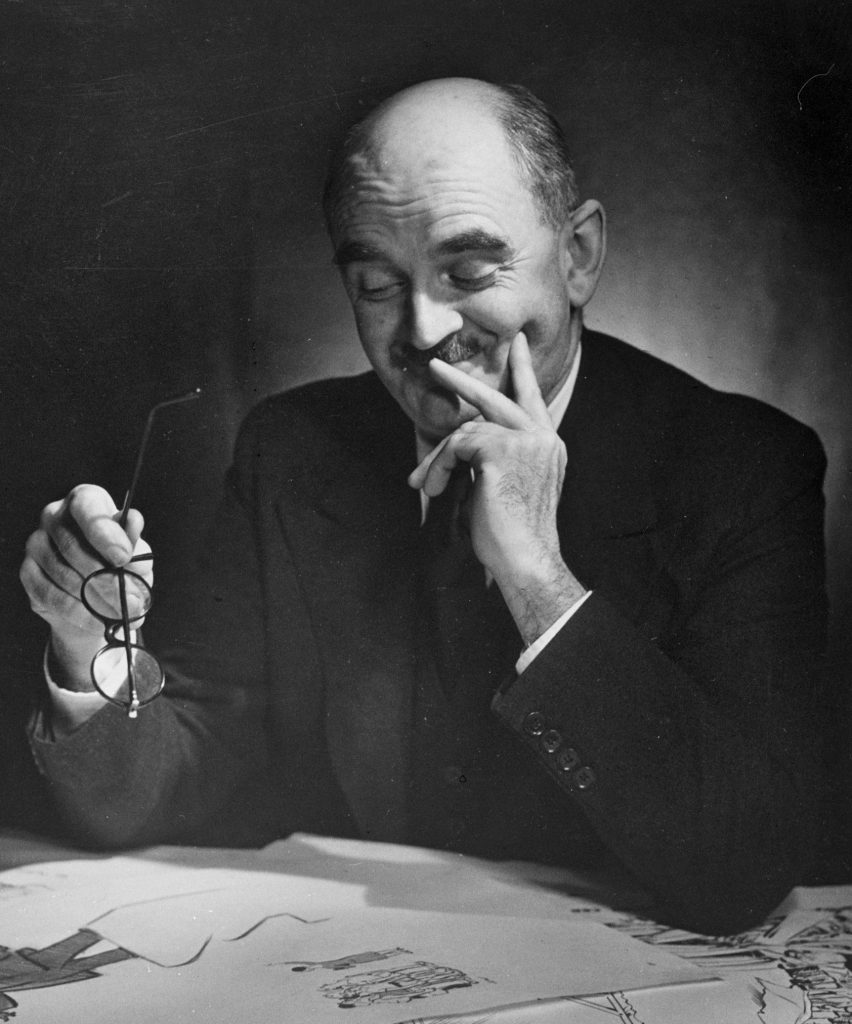

Let us now turn to David Low, the creator of this cartoon, and see how he saw the whole episode.

When David Low wrote an autobiography several years later, he could not help but mention the Ahmadiyya protest on his cartoon. Below are his thoughts, taken from his autobiography:

“[The cartoon] brought a large number of letters, eulogizing and applauding, which surprised me, and an indignantly worded protest which surprised me even more from the Ahmadiyya Moslem Mission, which deeply resented Mahomet being represented as competing with Hobbs, even of his being represented at all. The editor expressed his regrets at the unintentional offence and regarded the whole thing as settled. But no…”

He went on to write:

“The whole incident showed how easily a thoughtless cartoonist can get into trouble. I had never thought seriously about Mahomet. How foolish of me […] I was ashamed of […] drawing him in a silly cartoon.” (David Low’s Autobiography, by David Low, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1957)

The Ahmadiyya mission in London received praise from Muslims all over for their protest in honour of the Holy Prophetsa.

Modern historians look back

Looking back, modern historians cannot help but admit that this protest not only helped express Muslim emotion about their Prophetsa, but also acted as a deterrent for future heart-breaking events for many decades.

How historians today acknowledge this contribution of the Ahmadiyya Jamaat, is summarised in this statement by a modern-day historian:

“Despite the indignation expressed in 1925, nobody’s life was threatened, let alone be taken. There was no fatwa.” (Outrage: Art, Controversy, and Society, by Richard Howells, Andreea Deciu Ritivoi and Judith Schachter, Palgrave MacMillan, 2012)

We have seen above the letter sent by the government to the Ahmadiyya mission in London. They expressed their regrets for not being able to officially intervene, yet showing their displeasure that it had even happened. The letter also states the officials having a private meeting on the matter with the editor of The Star. Details of this meeting were not mentioned.

However, as much detail as we have been able to obtain from the government’s records shows that this informal meeting – which took place in the foreign secretary’s office – was about being cautious in publishing something that could possibly injure the sentiments of a particular community; in this case, the Muslim community worldwide.

Today, historians agree to the peaceful nature of the Ahmadiyya protest – that persuaded the cartoonist, David Low, and the editor, Pope Wilson, to express their regrets publicly – as the best protest ever to have surfaced. Even the government, albeit unofficially, had to step in and remind The Star newspaper of its moral duties.

This was again due to the peaceful nature of the Ahmadiyya Community. Modern-day historians continue to acknowledge the strength and pragmatism behind the Ahmadiyya approach.

Below is an excerpt from a book published as lately as 2020:

“This is an interesting response from several perspectives. First, because rather than seeking to defend free speech […] the secretary of state for India Frederick Edwin Smith […] remarked that newspapers should be more aware of this kind of sentiment but, since the paper had already apologized, there was no need to take it further. Smith clearly, therefore, had no interest in seeking to defend the rights of the newspaper to include any public figure they wished in their cartoon and instead expected that the paper would be aware enough to self-censor. Second, there was enough awareness of Muslim views on depictions of Muhammad that the secretary of state was able to opine on the matter in a manner which suggested that not only were Muslim attitudes to Muhammad depictions common knowledge in government circles but that they were more widely understood as well.” (Courting Islam: US-British Engagement with Islam since the European Colonial Period, by Sean Oliver-Dee, Lexington Books, London, 2020)

Modern historians have also admitted that the Ahmadiyya Community was, back then, barely settled in Britain and their numbers too were greatly inferior to other Muslims. Nonetheless, their grand stance in safeguarding the honour of the Holy Prophetsa and emphatic protest held no bounds. The offenders were left with no choice but to apologise.

Here is an example of such reports:

“Low was surprised by the exaggerated praise for his cartoon, but he was even surprised when an ‘indignantly worded protest’ arrived from the Ahmadiyya Muslim Mission in London. The Mission was just laying the foundations for the capital’s first mosque, and it took offence at the inclusion of Muhammad as one of the minor statues, looking admiringly up at Hobbs. Wilson Pope wrote to the Mission, and ‘expressed his regrets at the unintentional offence’ […]” (Showing politics to the people: cartoons, comics and satirical prints, by Nicholas Hiley, included in Using Visual Evidence, Ed. Richard Howells and Robert W Matson, McGraw-Hill OUP, New York, 2012)

The author also writes how Low had been reminded in the past in keeping religious sentiment in mind; however, those issues were never taken with the same seriousness as on this occasion.

The roots of extremism in protests

Whilst praising the Ahmadiyya protest, some Muslim groups came to the realisation that such could prove counterproductive to their anti-Ahmadiyya agenda. How could they simply praise them and stay quiet?

Zafar Ali Khan, in Zamindar, published an editorial piece in mid-October in an attempt to move the Muslim masses. He writes:

“We suggest that all the Muslims in the subcontinent, be it in towns or villages, take to their respective streets and gather in mass and pray:

“‘O, Lord! We are helpless. Deprived of worldly power. The Pharaohs of this age are disgracing yours and your Holy Prophet’ssa name. O God, give us the power to eliminate these oppressors and establish yours and your Holy Prophet’ssa honour.”

With this curse, Zamindar went on to provoke the Muslim masses:

“We have, until now, stayed quiet. And the disrespect towards the Holy Prophetsa has not enraged us. If only all Muslims would join hands in the above prayer!”

The Ahmadiyya Community gathered the whole affair was taking a turn for the extreme. Thus, Al Fazl, on 13 October 1925, copied the article from Zamindar and wrote:

“We don’t agree with the prayer written here, instead we present our own prayer:

“Lord! This blind world finds itself endlessly circling into the abyss. Enlighten them sense and wisdom so they may recognise Your Pure Being, Holy Prophetsa and spiritually embedded book […] don’t dishearten your weak but obedient people and save them from oppression. Through your grace and mercy, spread your true religion, Islam, to the corners of the earth so ignorant men might save themselves by refraining from disrespecting and humiliating You and Your Prophetsa. And after fulfilling the promise of واٰخرین منھم لما یلحقوابھم Islam might regain its former domination, majesty and glory.”

Hence, the Ahmadiyya Community distanced itself from the extreme views of other Muslims. However, Zamindar and other like-minded Muslims took root and extreme views toward The Star newspaper began to surface.

The Indian correspondent for The Morning Post, London, reported great turmoil among the Muslims. They had taken to the streets while protesting. The correspondent also reported a threat given publicly by Muslims of Calcutta: “Had this happened in India, the world would have witnessed bloodshed”.

80 years on: The 1925 episode echoes

When historians, researchers and analysts study Muslims’ reaction to the cartoons published about the Holy Prophetsa, the majority always refer to the 1925 cartoon published in The Star. Usually highlighted is the reaction shown by the Muslim world when Denmark first published a cartoon of the Holy Prophetsa in 2005.

What was it that, on this occasion, that persuaded Muslims to take up arms against the cartoonists and publishers and even the innocent public?

It is widely thought that the Ahmadiyya Community’s peaceful and dignified reaction of 1925 led to the matter being handled with elegance and excellence. This credit could not be left for the Ahmadis; therefore, the Muslims felt compelled to take an approach that went beyond the Ahmadiyya response.

In 1925, the Calcutta correspondent of The Morning Post reported the non-Ahmadi Muslim reaction thus:

“[…] quite unwittingly, the cartoon has committed a serious offence which, had it taken place in this country [i.e. India], would almost certainly have led to bloodshed.” (Religious Offence and Human Rights: The Implications of Defamation of Religions by Lorenz Langer, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2014)

Langer goes on to comment:

“More than eighty years later, the warnings from The Morning Post correspondent should have sounded eerily prescient when the publication of another cartoon of Mohammed […] did indeed lead to bloodshed.” (Lorenz Langer)

It is rather unfortunate to notice that the rest of the Muslims, to part ways with the Ahmadiyya approach, chose violence as their expression on such incidents – thus strengthening the anti-Islam narrative more than anything.

When Jyllands-Posten published the caricatures of the Holy Prophetsa of Islam in 2005, Muslims had three choices – all tried and tested before them:

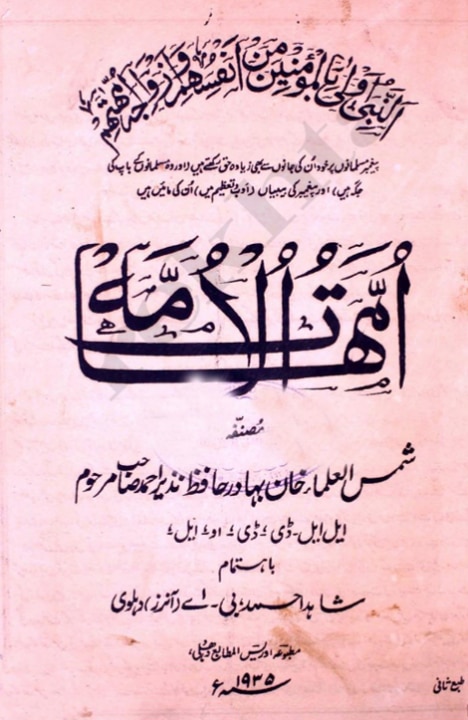

1. To respond in a similar manner as to that seen when Ummahatul Mominin – a seditious book about the Holy Prophetsa and his Wivesra – was published in 1897

2. To respond in the manner shown at the time of the 1925 The Star cartoon

3. Violence (which had become common since the atrocities of 9/11)

One Ahmad Shah Shaiq – a Muslim converted to Christianity – wrote a book titled Ummahatul Mominin in 1897 and ridiculed the character of the Holy Prophetsa of Islam. The book – as the author put it – was written in response to Muhammad Hussain Batalvi’s challenges which had frequented his newspaper Ishaat-us-Sunnah.

The publication of the book brought back a strong reaction from Muslim circles of India. Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas of Qadian, the founder of the Ahmadiyya community, condemned any reaction of violent or extremist nature, so much so that he saw no point in Anjuman-e-Himayat-e-Islam’s memorial that they had sent to the Government of India to proscribe the book.

He maintained his stance that such actions only attracted more attention for seditious material in question and, therefore, should only be responded to by replying to allegations so that readers get to see both sides of the picture. It was this approach of his that was to set an exemplary model for Ahmadis in particular and in general for other Muslims to take up in the wake of any such incident.

Muslims, however, remained so confused that even when any Muslim took it upon him to write a reply, they forgot about the actual contention and turned their guns towards the Muslim defender. The best example of such confusion is the book Ummahatul Ummah by Nazir Ahmad (commonly known as “Dipti” (Deputy) Nazir Ahmad in Urdu literature).

A well-respected Muslim, Nazir Ahmad, was seen as more of a foe than a friend for the mere reason that he had not used venerating salutations with the names of the Holy Prophet’ssa family as was customary in Urdu writing. Muslim scholars confiscated all copies of his book, heaped them in a large gathering of Nadwat-ul-Ulama and burnt them all to ashes. Nazir Ahmad, a seasoned and esteemed writer of Urdu, is said to have been left so heartbroken that he never put pen to paper ever after. (Ganjina-e-Gauhar, Shahid Ahmad Dehlvi, Karachi, 1962)

This one incident is sufficient to prove that Muslims – in their attempt to always remain distinct from the Ahmadiyya approach – had embarked upon a route of extremism which was to stay with them forever; even to get worse with time.

Then there was the precedent set by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat in 1925 in response to the cartoon that appeared in The Star. The Muslims, again, had shown a differing approach by threatening of violence – as The Morning Post had reported back then, and we have quoted above.

The third option was to take up arms against the perpetrators. This is what the anti-Islam circles desired and this is exactly what they achieved through a foolish cartoon. The Muslims fell prey to the plot and their violent reactions worked to strengthen the Islamophobic propaganda.

The following analysis by Anja Kublitz sums up the stimulus/response chain concisely:

“The cartoon controversy mirrors 9/11. Whereas the attack on the Twin Towers, a symbol of capitalism and Western world, created a political platform on which Western nations could unite and initiate the ‘global war on terror’, the insulting of the Prophet, the main symbol of Islam, created a platform that Muslim communities could use to counter Western hegemonies” (The Cartoon Controversy, by Anja Kublitz, in Social Analysis, Vol 54, Issue 3, 2010)

The extremist reaction shown by the majority of the Muslim world to the Danish cartoons of 2005, is summed up by Lorenz Langer (cited above) as follows:

“Over the ensuing months, outrage over the cartoons and their republication by numerous European papers spread through the Muslim world: Danish goods were boycotted, and the embassies of Denmark and other European countries in Beirut, Damascus and Teheran were assailed and even torched by protesters. Since 2005, more than 100 people have died and over 800 were injured in protests related to the cartoon.”

Whilst the rest of the Muslims reacted to the audacious caricature published by Denmark in 2005 with bloodshed, the spiritual head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Vaa responded in the most Islamic manner. The very same example was shown by the Ahmadiyya Community when journalism launched its very first major attack in the name of “freedom of speech”.

The headquarters of the Ahmadiyya Community had by then relocated to London. An opportunity for competing against the Western idea of freedom of speech from within had presented itself. In other words, an even greater challenge than before.

At a time like this, the spiritual head of the Ahmadiyya Community brought attention to highlighting the life of the Holy Prophetsa. He himself gave a series of sermons in order to highlight the excellent life and character of the Holy Prophetsa. He prayed for such unaware cartoonists and journalists and instructed his community to pray that Allah enabled them to understand the beauty of the Holy Prophet’ssa character. He encouraged the Ahmadiyya Community to do whatever was in their capacity to highlight the magnificence of the Holy Prophet’s life.

Right at the onset of his Khilafat, Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmadaa, Head of the worldwide Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, had focused on demystifying Islam. Having taken office as Khalifatul Masih in the spring of 2003, he found Islam tangled in misconceptions and allegations of all sorts; it had turned into a synonym of violence. As part of the very first steps he took to counter the situation, he launched the Peace Symposium from London which started to function as a rebuttal of allegations against Islam and its Holy Founder.

By 2006, the platform was fully functional and worked as a great means to rid Islam of attacks lodged on it by the anti-Islamic forces. Alongside using this platform, he delivered a series of sermons – from 10 February to 10 March 2006 – to refute all allegations that led the Western world to see the Holy Prophetsa of Islam as nothing more than a warlord and an instigator of violence.

Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad, Khalifatul Masih Vaa has, ever since, travelled to a large number of countries around the world and has spoken to parliaments, conferences, receptions and press conferences about the peaceful nature of Islamic teachings. He is, without a doubt, the only person to have strived to this extent on an awareness-raising campaign about Islam and its Holy Founder.

While in Copenhagen – the birthplace of Danish cartoons of 2005 – a reception was held in his honour. Mayors of various Danish cities, parliamentarians, politicians, members of the press and the intelligentsia comprised his audience as he delivered his address that evening. The audience was all ears to his words:

“A charge that is often levelled at Islam is that it was spread violently by the sword. This allegation is completely unfounded and indeed nothing could be further from the truth. All of the wars fought during the life of the Holy Prophetsa and the four rightly guided Caliphs who succeeded him, were entirely defensive in nature, where war had been forced upon them.”

He went on to state:

“Even here in Denmark, some years ago, there were cartoons printed that sought to ridicule the Foundersa of Islam and to portray him, God forbid, as an imperialistic leader and belligerent warmonger. This unjust portrayal of the Holy Prophet Muhammadsa defies history and defies the truth. The reality is that the Holy Prophetsa was forever enslaved by his determination to establish peace and the rights of humanity.” (For further details: www.pressahmadiyya.com; World Crisis and the Pathway to Peace, by Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmadaa, accessible at www.alislam.org)

At the end, I would like to put my personal affiliation with the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community and my allegiance to Hazrat Khalifatul Masihaa aside, when I make the following claim:

Thorough research has led me to believe, without any doubt, that Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmad is, in this day and age, the defender of Islam and its Holy Founder par excellence. So is the community that he leads; it always has been.

I have presented my research above to prove my point. Should someone wish to contest it, they are welcome to come forward, as long as their claim comes with a same or similar level of evidence-based research. Alhamdulillah!

(Translated by Tahmeed Ahmad, UK)

Respect, much to the Ahmadyya Muslim community in every way.

Let’s pray for a peaceful coexistence among the tyrants and saints.

Assalaamu ‘alaikum.

I see no justification in Islam for the demand to ‘set the law in motion against the offenders’. Such calls for punishment may please some Muslims, but go against what the Qur’an teaches.

The Qur’an affords complete freedom of belief, and with it, the freedom to speak well or ill of any religion, without any prescription of punishment for the offenders at the hands of other humans.

It is the believers who are taught to refrain from reviling false gods and blasphemy, but not under threat of punishment at the hands of their fellow human beings; rather, because it is a sin punishable by God Almighty.

It would be best for Muslims to abide by what the Qur’an teaches, which is to exercise patience and piety when hurtful statements are made [3:187], and to simply admonish those who mock, that they may fear God [6:70].

Wassalaam.

What a wonderful analysis of the history of peaceful protests of Ahmadiyya Community against cartoons and their peaceful Results! A must read! May Allah bless you for your efforts and allow you to further publish such well researched articles. Ameen!