Asif M Basit, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre

Never has the Royal Family of the United Kingdom been so much under the spotlight as since the death of Queen Elizabeth II. This unprecedented media coverage of royalty has called for many discussions – some suggesting that the garden is all rosy, others pointing to the thorns around the roses.

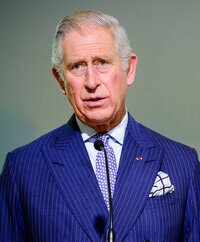

What prompted this article is a discussion I happened to hear on BBC about what the age of King Charles III will be referred to as – whether it will be the Carolean era or would the historian just see it as the era of the House of Windsor.

Well, it could be known as both, and why not? His Majesty King Charles III is a descendant of the House of Windsor and is the bearer of, as he himself has reiterated on many occasions, its long-spanning legacy. But before moving on, a quick look at the House of Windsor.

The Royal House of Windsor

With the death of Queen Victoria, the reign of the House of Hanover came to an end and, as her son and successor being a descendant of Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg & Gotha, Edward VII’s era was styled as the reign of the House of Saxe-Coburg & Gotha.

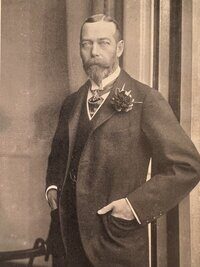

When Edward VII died in 1910 and his son ascended the throne, he was titled King George V and, naturally, the reign was seen as a continuation of the same royal house. However, the era of George V witnessed major upheavals in the European political landscape.

Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany and Tsar Nicholas II of Russia had been ferociously forced to abdicate amidst unprecedented civil unrest and uprisings of their own subjects. Both kings were grandsons of Queen Victoria, and so was King George V.

Having seen the terrible fate of his cousins, George V deemed it right to disassociate himself and the British monarchy from their German ties. Another stimulus was the anti-German sentiment that had steadily grown in the United Kingdom in the wake of World War I.

Thus, King George V issued a proclamation in the summer of 1917, stating:

“Whereas We, having taken into consideration the Name and Title of Our Royal House and Family, have determined that henceforth Our House and Family shall be styled and known as the House and Family of Windsor:

“And whereas We have further determined for Ourselves and for an on behalf of Our descendants and all other the descendants of Our Grandmother Queen Victoria of blessed and glorious memory to relinquish and discontinue the use of all German Titles and Dignities. […]

“Now, therefore, We, out of Our Royal Will and Authority, do hereby declare and announce that as from the date of this Royal Proclamation Our House and Family shall be styled and known as the House and Family of Windsor, and that all the descendants in the male line of Our said Grandmother Queen Victoria who are subjects of these Realms, other than female descendants who may marry or may have married, shall bear the Name of Windsor:

“And do hereby further declare and announce that We for Ourselves and for and on behalf of Our descendants and all other the descendants of Our said Grandmother Queen Victoria who are subjects of these Realms, relinquish and enjoin the discontinuance of the use of the Degrees, Styles, Dignities, Titles and Honours of Dukes and Duchesses of Saxony and Princes and Princesses of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and all other German Degrees, Styles, Dignities, Titles and Honours and Appellations to Us or to them heretofore belonging or appertaining.” (The London Gazette, 17 July 1917, Number 30186. Capitalisation and punctuation according to the original and not by the author)

So now we have King Charles III, a descendant of the House of Windsor and one who pledges to carry the mantle passed down to him.

Before going on to see what this mantle actually stands for, we need to address a question that is now coming to the surface in bolder tones than ever before:

The Ahmadiyya and their loyalty to the British Monarchy

While the death of Queen Elizabeth II saw her veneration across television channels around the world, more so in the UK of course, her link to colonialism and white supremacy was also voiced by certain circles.

And with this, the question of Ahmadiyya loyalty to the British monarchy has gained a bit of momentum, hence calling for it to be addressed, albeit briefly.

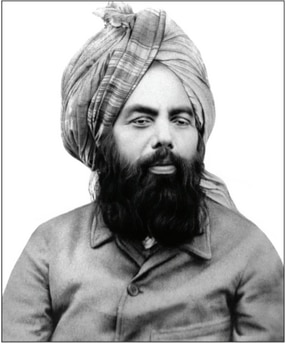

The Ahmadiyya tradition of loyalty to the British monarchy started naturally with the writings of Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas, the founder of the Islamic sect known as the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat. He was born in the time of the British Raj and remained a British subject, living all his life in British India.

This alone was enough to justify his loyalty and his call for all British-Indian subjects for the same. It was, and is, an Islamic tenet for a citizen to remain loyal and faithful to the ruler of the land.

However, he emphasised that this sentiment of loyalty stemmed from the freedom of faith that all citizens had under British rule – something that the erstwhile native rulers had failed to provide. Where Christians enjoyed freedom, Muslims too were free to call their azan, perform their religious rituals and profess and proselytise their faith; the same was the case for adherents of all other faiths – many as they were – in the vast Indian Subcontinent.

It was not only Hazrat Ahmadas who practised and called for this loyalty from among the Muslims; there was rather a significant number of individual Muslim scholars and Islamic anjumans that expressly stood for the same – heavily dotted across the vast length and breadth of India.

Letters of loyalty to Queen Victoria, and her successors, from this Anjuman-e-Ishaat-e-Islam to that Muslim council, can easily be accessed in the National Archives of India and the India Office Records – the transmitting and the receiving ends respectively.

When this query is addressed adequately, the next question posed is why the Ahmadiyya do not take into account the atrocities carried out by the British in their colonial pursuits. To address this, we must travel back in time to the days when colonial expeditions were at their apex – the age of European Imperialism.

Imperial expansion was not something invented by the European monarchs. It was a centuries-old practise of empires – headed by their emperors and empresses – to take into their pale any land that they possibly could. It was, as they say, a game of thrones – a game where the mighty one makes the rules, or breaks them as and when it suits them.

The Islamic Empire too has remained, and remains to this day, under harsh scrutiny for its territorial expansion in its medieval heyday.

The Ottoman Empire, with all its glorious claims of being the true successor of the Prophetsa of Islam, remained far from hesitant when it came to territorial expansion, even by unfair and shamelessly violent means.

Ironically, when the Khilafat Movement took off among Muslims of British India, they would not have forgotten the Armenian genocide carried out by the Ottoman Emperor (or the so-called Khalifat al-Muslimin).

But the Muslim support for the Ottoman Empire was based on a religious sense of belonging and not the geopolitical ambitions of its emperor-caliphs. The Indian Muslims had envisaged Turkey – the heartland of the Ottoman Empire – as a safe haven where they could live as a Muslim under a Muslim ruler. This being the raison d`etre of the Khilafat Movement, all other geopolitical shenanigans of the empire were placed aside as they mobilised Muslims to join the cause of rescuing the empire and the emperor.

Muslims in the Land of a Christian Monarch

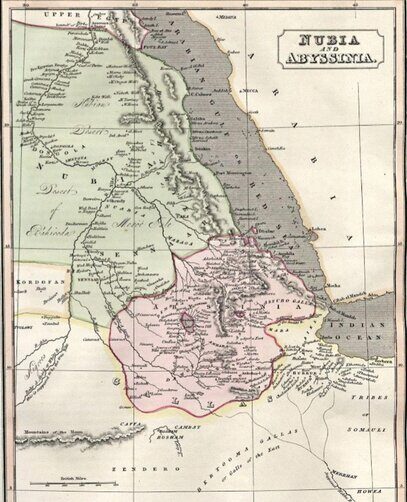

All this is modern history. Let us go back to the early days of Islam. It had been only five years since the Prophetsa of Islam had made his claim. The Meccan opposition was rife and the Muslims were persecuted ruthlessly. To enable his followers to profess and practise their newfound faith freely and fearlessly, the Prophetsa ordered a handful of them to seek refuge in Aksum, the headquarters of the Aksum Empire – one of the four major empires that enveloped pre- and early-Islamic Arabia. This is commonly referred to as hijrat-i-Habsha (migration to Abyssinia) in Islamic works.

All Muslim historians – classical and modern alike – unanimously agree that:

“The idea of leaving a country where injustice, oppression and persecution are prevalent, and taking refuge somewhere where the Muslims can gather their forces before returning to renew their quest for life according to Islamic principles, is a key idea in Islam, repeated often in the subsequent history of Islamic revivalist movements.”[1]

This quote, taken from a work of modern historians, can be verified in the classical works of Ibn Hisham[2] and Ibn Ishaq,[3] and subsequently in the accounts of commentators like al-Tabari,[4] Ibn Kathir[5] and Ibn Khaldun.[6] The event has been celebrated in Islamic literature by the likes of Ibn al-Jawzi and Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti and Muhammad bin Abd al-Baqi al-Bukhari al-Makki, to name a few from among hundreds, if not thousands of works produced in what can be called a genre dedicated to the significance of this migration.[7]

“Hence”, very rightly states Hussein Ahmed, “the hijra to Aksum is comparable to, or as decisive as, the hijra to Medina which took place in 622.”[8]

It is noteworthy that none of the above-mentioned Islamic stalwarts raised an eyebrow, even slightly, on the fact that Ashama bin Abjar – the King of Aksum who offered refuge to this group of Muslims, and Negus being the royal title of Aksum kings – was a Christian monarch who reigned over a Christian empire.

No one has ever scrutinised these asylum seekers – or the Holy Prophetas at whose behest they had fled – on this migration, let alone eulogising the king, his kingdom and his good nature. The simple reason, to which I very much agree, as any Muslim would, is that the scope of this reverence remains encircled around his good deed to have taken a persecuted community under his protection; to having allowed them to practice their faith and enjoy the same rights as did the indigenous subjects of the empire.[9]

No one who commemorates the Negus’ good deed is concerned with how the Kingdom of Aksum had come into existence, how much bloodshed its conquest of the African Horn might have resulted in and what went on in the military expeditions that led to its prosperity.

How the previous kings of Aksum – centuries before the Muslim migration – had sent expeditions to obtain gold from Sasu – a land beyond the border of modern-day Sudan – remains insignificant in the Muslim migration saga of the seventh-century CE.[10]

No one feels the need to testify how the Aksum king Kaleb – a predecessor of Negus Ashama bin Abjar – had gained victory over the Himyarite Kingdom of Southern Arabia (modern-day Yemen) on his first military expedition across the Red Sea. Neither is it deemed important that he conquered the land, toppled the Himyarite king, and appointed an Aksum viceroy in the conquered land.[11]

The subsequent uprising of the Himyarites against the Aksum occupation called for the Byzantine emperor Justin, urging Kaleb to retaliate and promising to back him with any support required, remains an issue beyond consideration. All other military massacres of Kaleb against the Persians fall in the same class.[12]

It might not be commonly known, but I write this on the authority of Ibn Hisham, that Hazrat Zubayr bin al-Awwam fought in the Negus’ army against a native rebellion.[13]

Tradition has it, as recorded by Ibn Hisham, that when a local Abyssinian rebelled and took up arms against the Negus, Zubayr bin al-Awwam crossed the entire breadth of the River Nile, floating on an inflated leather balloon, to go and fight with Negus – the Christian king of a Christian empire – and helped him crush the rebellion.

The same tradition goes on to record a statement of the refugee Muslims that remained behind that they indulged themselves in praying for the victory of Negus over the rebels. Their prayers continued until they saw Zubayr running back towards them, excitedly crying, “Rejoice, for the Negus is victorious. Allah has destroyed his enemy.”[14]

This is how the Muslim refugees reciprocated the good deed of Negus and expressed their loyalty and allegiance to the Christian Kingdom of Aksum. This also proves that one can have a political allegiance to a non-Muslim ruler, alongside a spiritual one to a prophet, a caliph or sage.

This goes to testify Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmad’sra viewpoint that he presented before the Khilafat Movement activists stating the Ahmadis take his allegiance as their Khalifa, while also of King George V as the ruler of the land. Swearing allegiance to the ruler of the land is only but a very Islamic act and does not mean a compromise of one’s faith; nor does it mean an endorsement of all political activity that happens at the behest of such rulers.[15]

It was on the throne of Himyar – the southern belt of the Arabian Peninsula – that Abraha was later appointed as viceroy of the Kingdom of Aksum. Yes, the same Abraha who, with a mahout army, advanced from his seat in Himyar towards Mecca with the intention to raze the Ka‘bah and establish the supremacy of his own church at Sanaa as the premier place of Pilgrimage.[16]

Thus, the only thing that matters, and should matter, to Muslims today is the gracious act of the Negus of Abyssinia towards the nascent Muslim community that sought refuge in his land. The fact that they expressly made their loyalty to the Negus known, through word of mouth and action alike, was exemplary in that it serves, to this day, as a prototype for Muslims living under non-Muslims rulers, as long as the latter ensures freedom of faith.

To end this note on Abraha’s malicious attempt to invade the Ka‘bah, we must briefly mention that the Aksum king Kaleb had resented the two expeditions of Abraha to Arabia – one of which is testified to by the Holy Quran in the chapter titled al-Fil (the elephants). The Aksum Kingdom, condemning his atrocities, broke ties with Abraha who went on to enthrone himself as King of Himyar. Thus, the Kingdom of Aksum disassociated itself from the worst brutality exercised in their name.

Interesting it is to note how kingdoms can draw a line in history and start afresh. The disassociation of the British Monarchy from the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and refashioning itself as the House of Windsor can be seen in a similar light.

Just as the Holy Prophetsa and his Companionsra had put aside any political, ideological and religious differences, and had remained thankful to the Negus, we as Ahmadi Muslims follow their example and express our gratitude to the British Monarchy for the benevolence it has shown for a persecuted Muslim community as well as for other sects of other faiths.

The dawn of the House of Windsor

John Buchan, a biographer of King George V, has aptly described the state of society when the era of the House of Windsor began:

“The simpler Victorian confessions were assailed by the sceptical influence of a fast-developing physical science. […]

“Most of the famous creeds, orthodox and heterodox alike, were shaken in popular esteem. […]

“This weakening of intellectual foundations was accompanied by an apparent loosening of civilisation’s cement, which is a reverence for law and order and a general goodwill. […]

“The fear of God was not a common mood. […]

“It was a world without a strong common faith and purpose, fumbling with ill-understood novelties, already half the servant of the intricate machine it had devised. […]

“Only here and there, a disconsidered prophet foretold that such a situation could not endure, and that sooner or later must come the thunderstroke to rend the lordly pleasure-house.

“In such a difficult ‘climate of opinion’ the new reign began”.[17]

It was undoubtedly the onset of religious bankruptcy. This loss of faith had resulted in moral degeneration that leads to conflicts and, thus, is a precursor of wars. Hitherto, England had sent missionaries to ‘heathen’ lands to call their people to the Christian faith. But with the meltdown of faith and belief at their very base back home, how credible could the missionary call sound?

In the aftermath of World War I, a strong sense of nationalism had awakened in the peoples of the colonies. They demanded independence in harsher tones than their colonial masters had ever heard. In this combination of challenges, religious and political both, Britain had to seek a conciliatory way where the political ideologies and religious beliefs of its subjects had to be honoured.

Freedom of faith and the House of Windsor

It was time to retract not only their geopolitical control but also the web of missionary societies functioning all over the colonial expanse. The tables had turned and a nascent Muslim sect, with its meagre resources, was now to send their missionaries to London – the heartland of the British Empire.

Only two years into the reign of King George V – in 1912 to remain precise – the first Ahmadiyya Muslim missionary had landed in Woking and was fully functional and calling the British public to Islam. Another year and a mission had been established in a street off the famous Edgware Road, only a stone’s throw away from Buckingham Palace and the Houses of Parliament – the nerve centre of British imperial outreach.

“The first organized effort by Indian Muslims to establish Islam in Britain”, notes Ron Geaves, “would come with the arrival of Ahmadiyya missionaries early in the second decade of the twentieth century.”[18]

This remarkable effort of a small sect, with next-to-none resources to fund a Muslim mission in London, became possible under the reign of King George V.

Reports from the British press show how the Ahmadiyya missionary singlehandedly proselytised Islam in almost every part of Great Britain. One day, he is reported to have lectured at Plymouth, the next day he is in Brighton. One week he speaks in Portsmouth, the following he is addressing the people of Liverpool and farther northern parts of the country. The results of this relentless effort did not remain inconspicuous, as observed by experts on Islam’s history in Britain:

“New converts in London would be predominantly middle- and upper-class men and women seeking an alternative religious and spiritual journey parallel to that of Christianity”.[19]

By 1920, the Ahmadiyya missionaries had purchased two houses in Southfields that came with a vast orchard adjacent to their back gardens. It was clear, from the point of purchase of this one-acre piece of the vast empire’s land, that it had been acquired for building a mosque. Correspondence with the local authority attests to this intention; and so does the report in The Times of 7 February 1921 – along with the rest of the British press, mainstream and local alike.[20]

It was a piece of land, albeit very small, in the land of an emperor who had only just relinquished the remnants of his German affiliation, refashioning his kingdom as the House of Windsor; an emperor whose title was, among many, the Defender of “the” Faith, where faith, owing to him being the head of the Church of England, referred specifically to Christianity. But he was happy to have let defenders of other faiths take up a piece of his own land.

It was around the same time, at the turn of the third decade of the twentieth century, that King George V sanctioned the plans for a British Empire Exhibition in London in 1924. Whereas the primary impetus behind the exhibition was to showcase the pomp and power of the British Empire, religions within the empire were given a fair share.

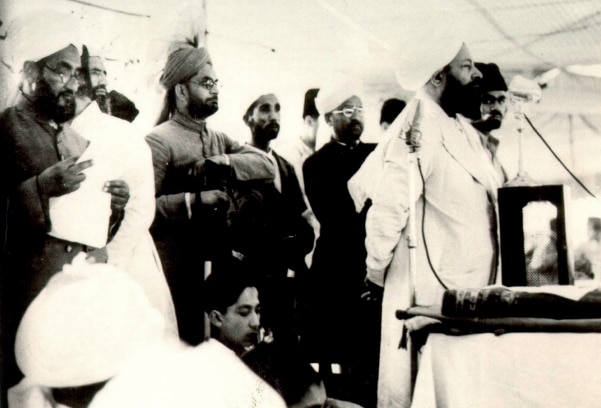

Under the auspices of King George V, the Conference of the Living Religions of the Empire was held at the Imperial Institute, London.

A speaker who was invited all the way from British India was Hazrat Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud Ahmadra, the head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community. He was to introduce Islam to the intellectual class of the Empire’s capital and to many others who had travelled from various parts of the Empire. His participation had hugely attracted the British press, which closely followed him throughout his two-month stay, so much so that Sir Denison Ross had to acknowledge how much the conference had benefited from his participation:

“We were specially gratified that the Khalifat-ul-Masih, the head of the Ahmadiyya Movement, immediately signified his intention to come to London with a number of his followers for the express purpose of attending the conference. This remarkable enterprise led to great publicity in the Press and secured considerable interest for our Conference.”[21]

This whole enterprise goes to show King George V’s tolerance for religious diversity in his homeland, not to speak of the whole empire. But his advocacy for freedom of faith was yet to become clearly manifest when the head of the Ahmadiyya community was to lay the cornerstone of a mosque in London.

This historic event took place on 19 October 1924 and was wholeheartedly covered by the British press. The Times, Evening Standard, The Telegraph, London Illustrated News, The Sphere, all spearheaded the news story that no newspaper had missed. Headlines of most newspapers read: “London’s First Mosque”.[22]

One can imagine King George V, seated by a large window of Buckingham Palace on an autumn morning, reading the news of a mosque being built in London; smiling at how times had changed and tides had turned. This imagination is not a mere daydream. Reports of the conference have it that he had “sent his blessings”, through a telegram, to be read out in the inaugural session.[23] He knew what was happening, and was happy to allow it to be so – he wanted the candle of faith to not dwindle away in the wild hurricane of materialism.

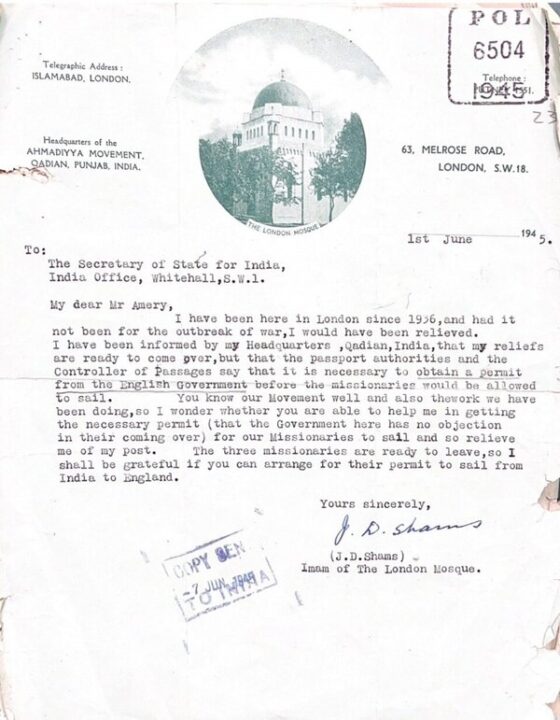

In October 1926, the Fazl Mosque – London’s first mosque – was ready and inaugurated. It was not just a mosque but a hub of British-Muslim participation in the socio-political process of the country. Indian delegates of the Round Table Conferences – inaugurated by King George V – attended the Fazl Mosque. The Imam of the London Mosque – as the title got to be known – would regularly communicate with the King and the Government on pressing issues and convey to them the messages of Hazrat Khalifatul Masih – replies received and passed through the same intermediary.

The Ahmadiyya mission in London remained functional under King George V and later during the reigns of his successor, George VI. And then started the reign of his granddaughter, Elizabeth II, which was to last for seven decades.

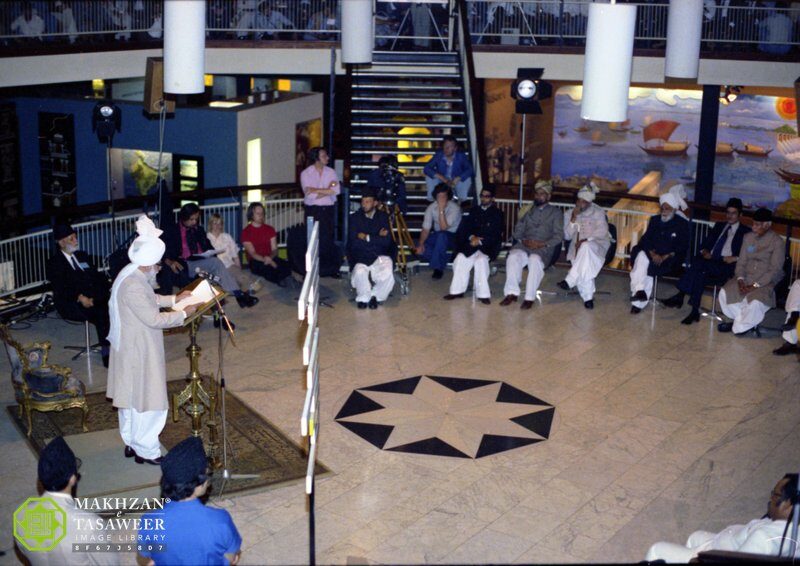

It was during the reign of Queen Elizabeth II, in the summer of 1978, that the Ahmadiyya Muslim community were to organise a conference in London, titled “Deliverance of Jesus from the Cross”. The theme of the conference was the Ahmadiyya belief that Jesus did not die on the cross, did not ascend physically to heaven, lived the rest of his life indulged in propagating his noble message and died in Kashmir.

The keynote address was given by Hazrat Mirza Nasir Ahmadrh, the then head of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community. For the Defender of “the” faith to allow a conference on a theme that aimed at the very tenet of “the” faith is something to appreciate and be grateful for. It was all about the supremacy of Islam over all preceding faiths, especially Christianity.

When the persecution of the Ahmadiyya community reached a stage where every atrocity against its members could be interpreted as legal and justified through the constitution, the headquarters had to be moved out of Pakistan, remaining where could mean allowing a spanner to be thrown in its works and halting the heartbeat of a globally functional community.

The then head of the Ahmadiyya community, Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmadrh, on the prototype of the Abyssinian migration, moved to London – bringing along the headquarters of the community. For him to have carried out his responsibilities freely, to have lived in peace from 1984 until his demise in 2003, and to be buried on British soil, again calls for a huge expression of gratitude to the House of Windsor.

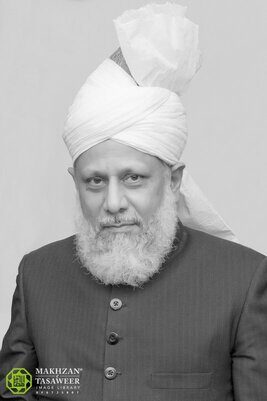

The present head of the Ahmadiyya community, Hazrat Mirza Masroor Ahmadaa, migrated to England upon the demise of his predecessor and assumed his office in the spring of 2003. He has thenceforth been leading the global community, propagating the message of Islam, advocating global peace and international justice – all without fear of any persecution in the land reigned by two monarchs of the House of Windsor: Queen Elizabeth II and, lately, King Charles III.

The Ahmadiyya Khilafat sees the example of the Holy Prophetsa of Islam as the best model of Muslim behaviour, and follows it. Hence, they have remained thankful to the British Monarchy for facilitating the message of Islam by providing a favourable atmosphere. Religious differences are put aside, as did the Holy Prophetsa, and gratitude is expressed for providing refuge to the headquarters of the Ahmadiyya community – a gesture of kindness and benevolence that no Islamic head of state has been able to extend to their coreligionist sect.

I close this article by briefly addressing another question. Why praise the monarchy when all laws are made by the parliament?

The answer is quite simple and straightforward: As long as the monarch remains the head of state, the monarch will deserve the special thanks of a community that lives under its reign and is allowed to disseminate the message of Islam from its land.

As Ahmadis, we are equally thankful to the British government – or as the formal title goes, to His Majesty’s Government – for their religious tolerance and their efforts to maintain an atmosphere in the society where freedom of faith and expression prevails; just as we are thankful to governments of all other countries where the Ahmadiyya Muslim community, and sects of all other faiths for that matter, live without the fear of persecution.

However, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Vaa has always conveyed to the monarch and to government dignitaries the message of Islam. Where he sees them at fault, he has openly made his reservations clearly known to them; as well as given them advice based on Islamic teachings.[24]

This is the beauty of Islam in action. The Ahmadiyya leadership remains faithful and thankful where they are given a favourable atmosphere for proselytising their faith. However, misgivings and disagreements on certain policies are laid bare without the slightest hesitation – powerfully, yet peacefully.

This exercise of expressing an opinion powerfully, yet remaining peaceful and loyal to one’s nation is probably what needs to be understood by those who remain sceptical of the issue discussed at length above.

References:

[1] Mohamed El Fasi and I Hrbek, The coming of Islam and the expansion of the Muslim Empire, in General History of Africa III: Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century, Heinemann Educational Books, London, 1988

[2] Ibn Hisham, al-Sirat al-Nabawiyya, Beirut

[3] Ibn Ishaq, Sirat Rasul Allah, Karachi

[4] Al-Tabari, Jami al-Bayan fi Tafsir al-Quran, Beirut

[5] Ibn Kathir, Tafsir al-Quran al-Uzma, Beirut

[6] Ibn Khaldun, Tarikh Ibn Khaldun, Beirut

[7] Ibn al-Jawzi’s Tanwir al-Ghabash fi fadl al-Sudan wal-Habash; al-Suyuti’s Raf’ Shan al-Habshan; al-Makki’s al-Tiraz al-Manqush fi Mahasin al-Hubush

[8] Hussein Ahmed, Aksum in Muslim Historical Traditions, in Journal of Ethiopian Studies, December 1996, Institute of Ethiopian Studies

[9] Muhammad Husein Haykal, The Life of Muhammad, translation by Ismail Raji al-Faruqi, Islamic Book Trust, Kuala Lumpur, 2002

[10] The Christian Topography, by a sixth-Century Christian monk Cosmas Indecopleustes, translation by JW McCrindle, Hakluyt Society, London, 1897; quoted by David W Phillipson, Foundations of an African Civilisation, James Currey, Suffolk, 2012

[11] Procopius, History of the wars II, translation by HB Dewing, Harvard University Press, 1916

[12] Ibid

[13] Ibn Hisham, al-Sirat al-Nabawiyya

[14] Ibid

[15] Masla turkiya ka hal

[16] AJ Drewes, Inscriptions de l-Ethiopie Antique, Leiden, Brill, 1962, and quoted by DW Phillipson Op Cit

[17] John Buchan, The People’s King: George V: A Narrative of Twenty-Five Years, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, USA, 1935

[18] Ron Geaves, Islam and Britain: Muslim mission in an age of empire, p.67, Bloomsbury, London, 2018

[19] Ibid, p. 68

[20] Details: Asif Basit, London’s First Mosque: A study in history and mystery, Review of Religions, London, July 2012

[21] Denison Ross, in Religions of the Empire, Ed William Loftus Hare, p. 5, Macmillan, London, 1925 (Capitalisation as in original and not the author’s)

[22] Details: Asif Basit, Islamic Caliphate: The missing chapters, Domum Historia, London, 2019

[23] Thomas Howard, The Faith of Others, p. 149, Yale University Press, 2021

[24] For instance: www.pressahmadiyya.com/press-releases/2019/03/head-ahmadiyya-muslim-community-warns-intensifying-global-hostilities-risk-disastrous-nuclear-war/