Ata-ul-Haye Nasir, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre

Ahmadiyyat continued to progress

Despite severe opposition from the Ahrar, Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya continued to flourish and marched towards its objective — propagating the message of Islam to all corners of the world.

Arjun Singh, editor of the newspaper Rangeen, states:

“Upon reading the Ahmadi newspapers, one finds that since the time Majlis-e-Ahrar has raised the alam-e-jihad [opposition] against Ahmadiyyat, the Ahmadi Jamaat is progressing with each passing day. Hence, their financial condition is better than before, their institutions are functioning with greater fervour, and not a day goes by without five to ten individuals from the [non-Ahmadi] Muslims joining Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya. We have come to know from some credible Ahmadis that they consider the Ahrar movement to be very beneficial for the progress of their Jamaat. Therefore, it is their claim that Ahrar could never succeed in effacing Ahmadiyyat. But rather, they believe that as long as the Ahrar continue their efforts to destroy Ahmadiyyat, harm and persecute them, the more will be the progress of Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya.” (Sair-e-Qadian, Sardar Press, Amritsar, pp. 29-30)

Ahrar and KL Gauba

Mr KL Gauba, also known as Kanhaiya Lal Gauba or Khalid Latif Gauba, son of Lala Harkishen Lal, converted to Islam in 1933. He was a politician and member of the Punjab Legislative Assembly from a Muslim constituency.

As far as his connections with the Ahrar are concerned, it is evident from the fact that in the 1934 general elections, KL Gauba contested the election as an Ahrar nominee. (Tarikh-e-Ahrar, p. 198; Karwan-e-Ahrar, Vol. 2, pp. 94-95)

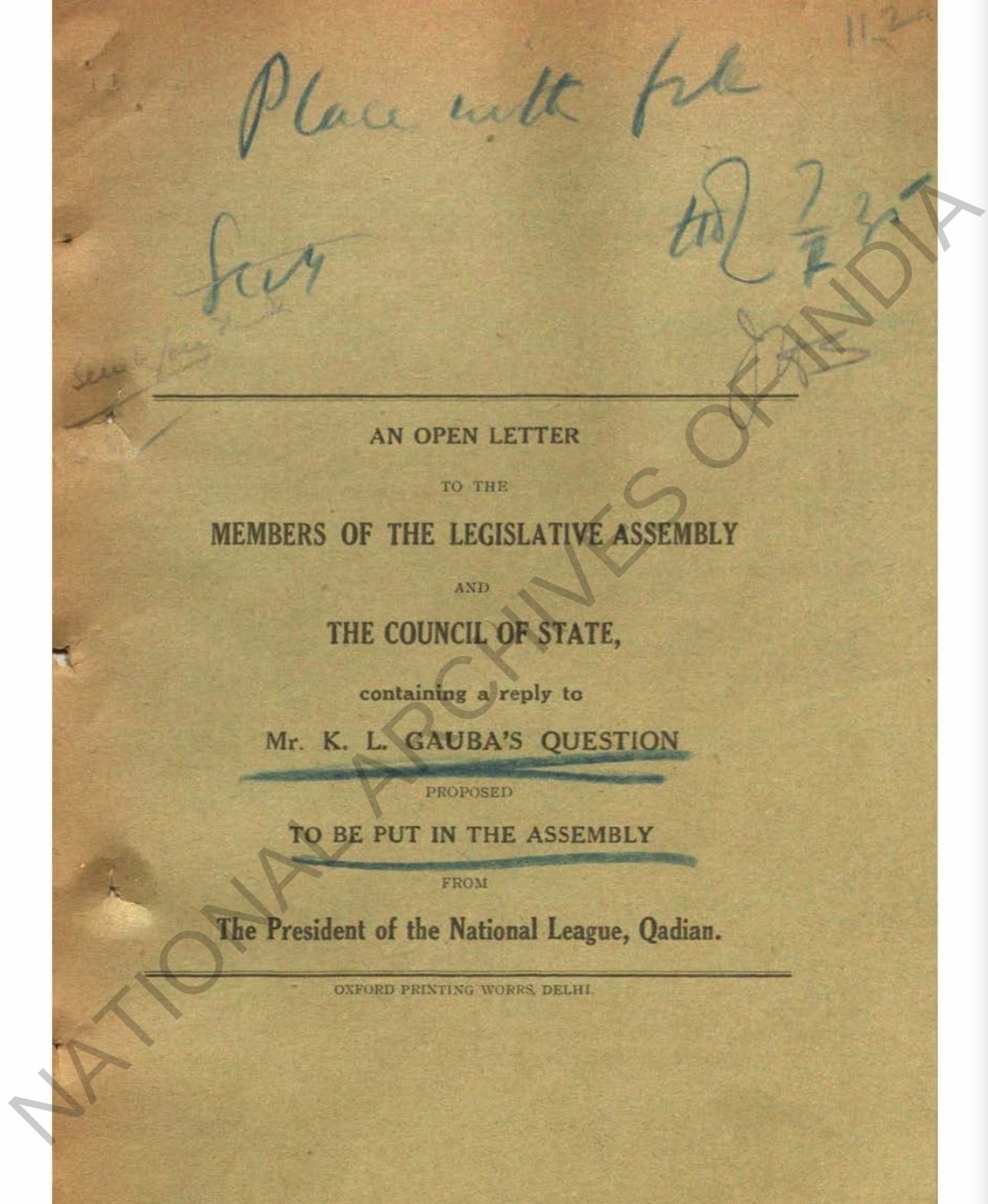

Mr Gauba’s anti-Ahmadiyya stance emerged openly when he raised false allegations against the Promised Messiahas and stated that, God forbid, he had disrespected the non-Ahmadi Muslims by using abusive language. He proposed to put the question in the Assembly whether the government was aware that the Founder of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community has, God-forbid, used “abusive” language against the non-Ahmadi Muslims. Mr Gauba’s false allegation was refuted in detail in the March 1935 issue of The Review of Religions. It was also published as An Open Letter.

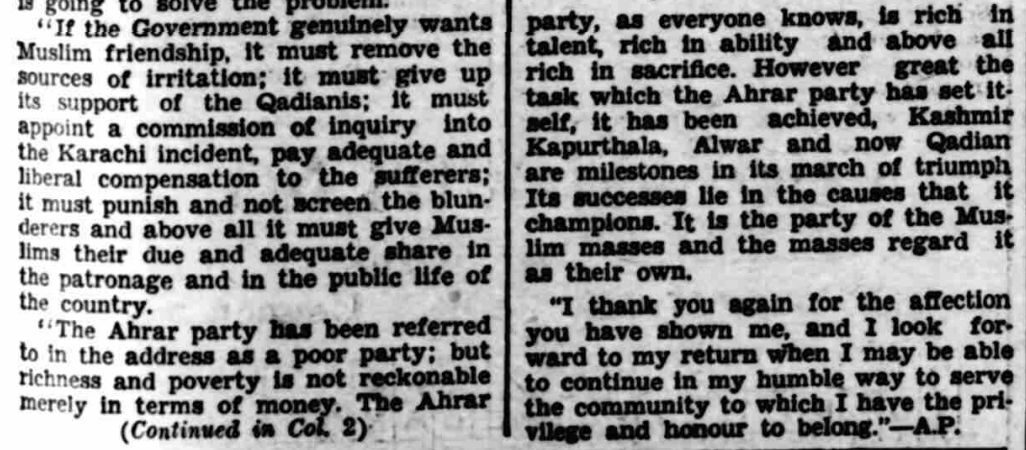

Mr Gauba once said, “If the Government genuinely wants Muslim friendship, it must remove the sources of irritation; it must give up its support of the Qadianis. […] However great the task which the Ahrar party has set itself, it has been achieved, Kashmir, Kapurthala, Alwar and now Qadian are milestones in its march of triumph. Its successes lie in the causes that it champions. It is the party of the Muslim masses and the masses regard it as their own.” (The Civil and Military Gazette, 16 May 1935, p. 7)

Muslim Tabligh Conference in Saharanpur

On 19 May 1935, Ataullah Shah Bukhari delivered a speech at the Muslim Tabligh Conference in Saharanpur and used inappropriate language against Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya. He asserted that Ahmadis were working against the interests of Islam and helping its enemies. A detailed report on this speech can be found at the National Archives of India (Government of India: Home Department [Political Section], File No. 36/5/35-Poll).

Ahrar Conference in Lyallpur

On 29 June 1935, an Ahrar Conference was held in Lyallpur [now Faisalabad], where a resolution was passed demanding the showing of Ahmadis “as a section separate from Muslims.” (The Civil and Military Gazette, 2 July 1935, p. 13)

Attack on Hazrat Mirza Sharif Ahmadra

On 8 July 1935, Hazrat Sahibzada Mirza Sharif Ahmadra, son of the Promised Messiahas, was attacked in accordance with a vicious plan by Ahrar. It was around 6 pm when he set off from his office on his bicycle for his residence that someone attacked him with a long and sharp club three times. Hazrat Mirza Sharif Ahmadra courageously blocked this sudden assault with sharp reflexes.

Accepting the responsibility for such a vile act, the official historian of Ahrar, Janbaz Mirza, states under the heading “Ahrar ki Anokhi Jasarat”:

“In those days, Master Tajuddin Ansari was in-charge of the Ahrar office in Qadian,” and he “formulated a plan. Accordingly, he prepared a youngster, Muhammad Hanif, who was the son of the beggars. He was given the responsibility to publicly beat Sharif Ahmad[ra], the brother of Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud[ra], Khalifa of Qadian, and then to run away from the scene.” (Karwan-e-Ahrar, Vol. 2, Maktaba Tabsarah Lahore, 1977, pp. 311-312)

Ahmadiyya-Ahrar situation discussed in the British Parliament

On 2 August 1935, the Ahmadiyya-Ahrar situation came under discussion in the House of Commons of the British Parliament.

Mr Charles Emmott from the Conservative Party asked the Under-Secretary of State for India, “Whether he is aware that grave and increasing unrest is being produced among the Ahmadiyya community at Qadian by the hostile activities of the Ahrar, and that these activities have assumed an aggravated form since October of last year; and whether he intends to take any measures to prevent their continuance?”

Mr Butler, the Under-Secretary of State for India, responded, “I am aware that there has been serious tension between the Ahmadis and Ahrars at Qadian since last autumn, which still unfortunately continues. The Government of the Punjab are keeping a close watch on the situation.”

Mr Emmott asked, “Will my hon. friend give an assurance that the Government of the Punjab will continue to watch this situation with close attention?”

Mr Butler responded, “I can certainly give the hon. member that assurance. The Government of the Punjab have been giving the matter very serious consideration.”

Then, Mr William MacColin Kirkpatrick of Conservative Party asked, “Is it not a fact that the two parts referred to are not Hindu and Moslem but are both Moslem?”

Mr Butler replied, “They are both Moslem.” (Hansard, HC Deb, 2 August 1935, Vol. 304, cc. 2982-3, https://api.parliament.uk)

Shahidganj Mosque and Ahrar

In the 18th century, during the Mughal rule in India, a mosque was built in Lahore, known as “Abdullah Khan Mosque”, later named the “Shahidganj Mosque”. Due to the historical background of its location, this mosque remained a cause of controversy between the Sikh and Muslim communities. On 8 July 1935, the Mosque was demolished by some members of the Sikh Community. This created a new wave of Sikh-Muslim disturbances. (The Civil and Military Gazette, 9 July 1935, p. 1)

Ahrar showed great passion at the beginning of this dispute and initiated civil disobedience, though their leaders had divided opinions on this movement.

The Ahrar were intensifying their violent acts in relation to this issue, and the then Governor of Punjab, Sir Herbert William Emerson, mentioned it to the then Viceroy of India, Lord Linlithgow, stating that “the Ahrars do not appear to have secured much Muslim sympathy, as it is generally recognised that their action has been inspired entirely by political motives.” (Punjab Politics, 1936-1939: The Start of Provincial Autonomy [Governor’s Fortnightly Reports and other Key Documents], Lionel Carter (ed.), Manohar, 2004, p. 154)

Thereafter, the Ahrar ceased their violent movement and claimed that this was in fact a conspiracy by Ahmadis against the Ahrar to damage them politically. Mentioning this, the Governor of Punjab wrote to the Viceroy, on 19 October 1936, and stated:

“The Ahrars had found a popular platform; they were entirely unscrupulous in making the best use of it; and by raising the cry of ‘Danger to Islam’ they were fast increasing their strength. Then came the Shahidganj incident. The Ahrars, believing that the Ahmadis were at the back of it, refused at a critical time to take the popular Muslim side. They lost a great deal of their influence and have not yet fully recovered the ground that was lost. But they have recovered a great deal of it, and because of their antagonism to the Ahmadia community, they gain more sympathy and support on this account than their merits deserve. They are anti-Government and have flirted with Congress from time to time. They have no outstanding leaders of position, but have several good mob orators and their Party is fairly well organised.” (Ibid, p. 51)

Two years later, the then Governor of Punjab Sir Henry Duffield Craik wrote to the then Viceroy of India Lord Linlithgow, on 10 May 1938, and stated:

“The Ahrar party has now announced its decision of abandoning civil disobedience, but unfortunately Maulana Zafar Ali Khan’s rival party, the Ittihad-i-Millat, has decided to continue the process, their decision being based, in the words of their resolution, on ‘the irreconcilable attitude adopted by the Akalis and Master Tara Singh and the wayward policy of the Majlis-i-Ahrar.’” (Ibid, p. 212)

Ahmadiyya response on Shahidganj Mosque issue

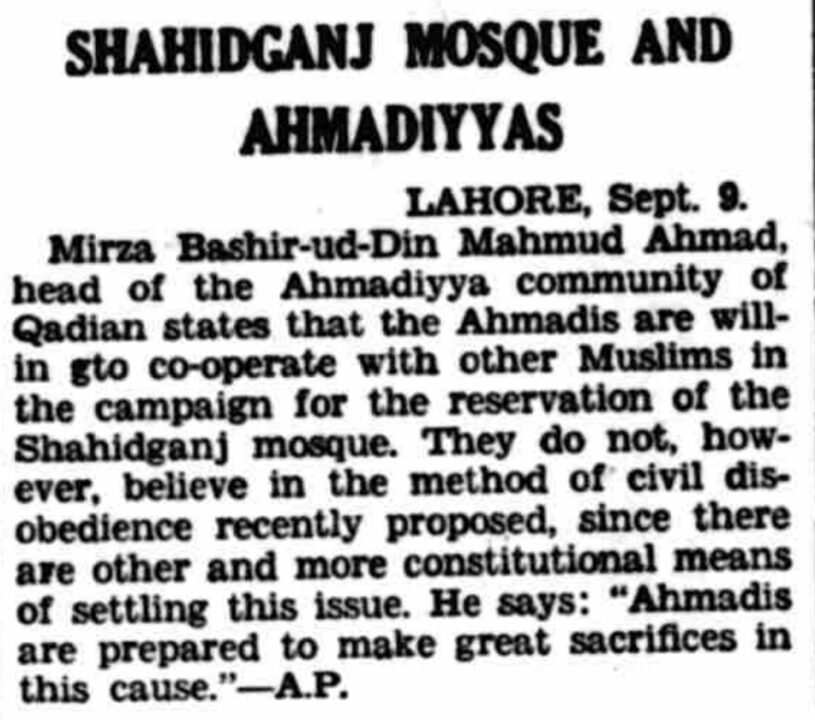

As far as the Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya’s response is concerned, The Civil and Military Gazette reported on 10 September 1935:

“Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad[ra], head of the Ahmadiyya community of Qadian states that the Ahmadis are willing to cooperate with other Muslims in the campaign for the reservation of the Shahidganj mosque. They do not, however, believe in the method of civil disobedience recently proposed, since there are other and more constitutional means of settling this issue. He says: ‘Ahmadis are prepared to make great sacrifices in this cause.’”

This news report was referring to the Friday Sermon of Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra, dated 6 September 1935, in which he refuted the Ahrar’s false allegation against the Jamaat that the dispute of the Shahidganj Mosque was created by the Ahmadis.

On one hand, Huzoorra categorically stated that the government could have avoided such an incident and the following chaos by taking preventive steps, and on the other, he made it clear that though Ahmadis would be ready to cooperate with the Muslim community in a peaceful way, it could never support any kind of violence such as civil disobedience. Huzoorra also granted valuable guidance and advice to the Muslims as to how they should have reacted and what steps they needed to take in the future. (Khutbat-e-Mahmud, Vol. 16, pp. 562-568)

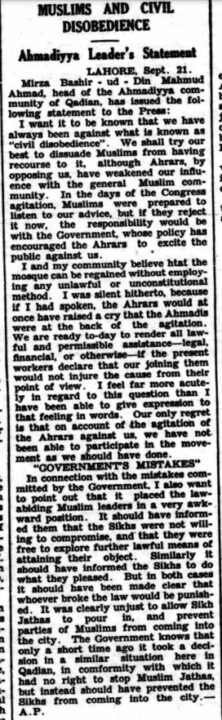

Huzoorra also issued the following statement:

“I want it to be known that we have always been against what is known as ‘civil disobedience’. We shall try our best to dissuade Muslims from having recourse to it, although Ahrars, by opposing us, have weakened our influence with the general Muslim community. In the days of the Congress agitation, Muslims were prepared to listen to our advice, but if they reject it now, the responsibility would be with the government, whose policy has encouraged the Ahrars to excite the public against us.

“I and my community believe that the mosque can be regained without employing any unlawful or unconstitutional method. I was silent hitherto, because If I had spoken, the Ahrars would at once have raised a cry that the Ahmadis were at the back of the agitation. We are ready today to render all lawful and permissible assistance—legal, financial, or otherwise—if the present workers declare that our joining them would not injure the cause from their point of view. I feel far more acutely in regard to this question than I have been able to give expression to that feeling in words. Our only regret is that on account of the agitation of the Ahrars against us, we have not been able to participate in the movement as we should have done.

“Government’s Mistakes

“In connection with the mistakes committed by the Government, I also want to point out that it placed the law-abiding Muslim leaders in a very awkward position. It should have informed them that the Sikhs were not willing to compromise, and that they were free to explore further lawful means of attaining their object. Similarly it should have informed the Sikhs to do what they pleased. But in both cases it should have been made clear that whoever broke the law would be punished. It was clearly unjust to allow Sikh Jathas to pour in, and prevent parties of Muslims from coming into the city. The Government knows that only a short time ago it took a decision in a similar situation here in Qadian, in conformity with which it had no right to stop Muslim Jathas, but instead should have prevented the Sikhs from coming into the city.” (The Civil and Military Gazette, 22 September 1935, p. 7)

Ahrar’s anti-Ahmadiyya activities echoed in Hejaz

In a letter dated 21 January 1936, the then Undersecretary to the Foreign Affairs of Saudi Arabia, His Excellency Fuad Bey Hamza, inquired about Majlis-e-Ahrar from the Indian Government’s Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary in Saudi Arabia, Sir Andrew Ryan.

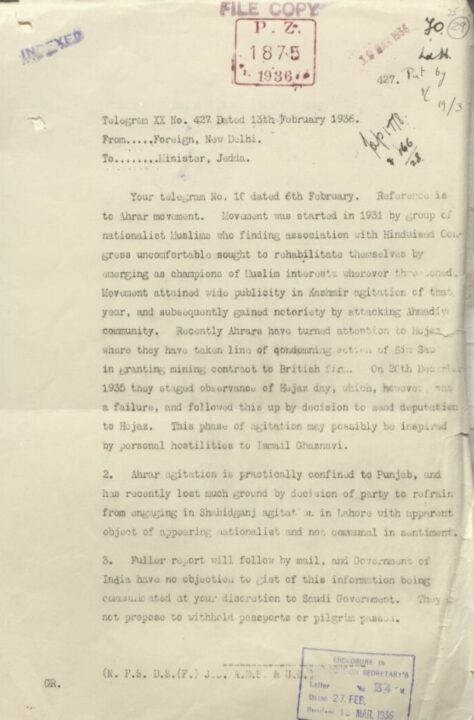

Sir Ryan sent a telegram to the Foreign Office in New Delhi on 6 February and received the following response on 13 February:

“Your telegram No. 10 dated 6th February. Reference is to Ahrar movement. Movement was started in 1931 by group of nationalist Muslims who finding association with Hinduised Congress uncomfortable sought to rehabilitate themselves by emerging as champions of Muslim interests wherever threatened. Movement attained wide publicity in Kashmir agitation of that year, and subsequently gained notoriety by attacking Ahmadiya community. Recently Ahrars have turned attention to where they have taken line of condemning action of Bin Saud in granting mining contract to British firm. On 20th December 1935 they staged observance of Hejaz day, which, however was a failure, and followed this up by decision to send deputation to Hejaz. This phase of agitation may possibly be inspired by personal hostilities to Ismail Ghaznavi.

“Ahrar agitation is practically confined to Punjab, and has recently lost much ground by decision of party to refrain from engaging in Shahidganj agitation in Lahore with apparent object of appearing nationalist and not communal in sentiment.” (Coll 6/11 ‘Hejaz-Nejd Affairs: Economic Development in the Hejaz’ [29r] (58/504), British Library: India Office Records and Private Papers, IOR/L/PS/12/2077, in Qatar Digital Library, www.qdl.qa [accessed 29 September 2023])

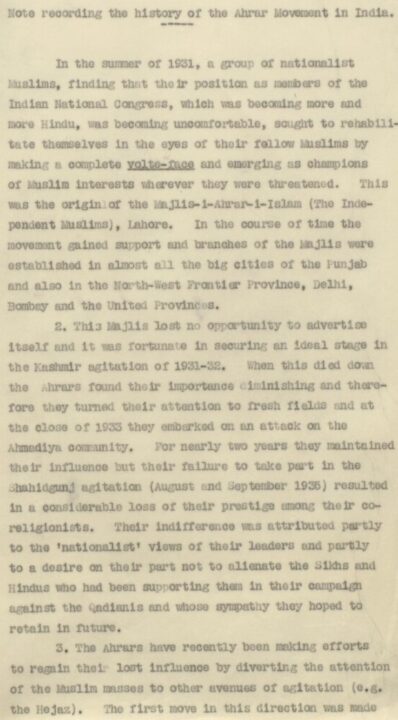

Thereafter, on 25 February 1936, Mr Metcalfe from the Foreign and Political Department of the Indian Government, sent a telegram to Sir Ryan, including a “Note recording the history of the Ahrar Movement in India”, which stated:

“This Majlis lost no opportunity to advertise itself and it was fortunate in securing an ideal stage in the Kashmir agitation of 1931-32. When this died down the Ahrars found their importance diminishing and therefore they turned their attention to fresh fields and at the close of 1933 they embarked on an attack on the Ahmadiya community. For nearly two years they maintained their influence but their failure to take part in the Shahidgunj agitation (August and September 1935) resulted in a considerable loss of their prestige among their co-religionists. Their indifference was attributed partly to the ‘nationalist’ views of their leaders and partly to a desire on their part not to alienate the Sikhs and Hindus who had been supporting them in their campaign against the Qadianis and whose sympathy they hoped to retain in future.

“The Ahrars have recently been making efforts to regain their lost influence by diverting the attention of the Muslim masses to other avenues of agitation (e.g. the Hejaz).” (Ibid, [32r] (64/504), British Library: India Office Records and Private Papers, IOR/L/PS/12/2077, in Qatar Digital Library, www.qdl.qa [accessed 22 September 2023])

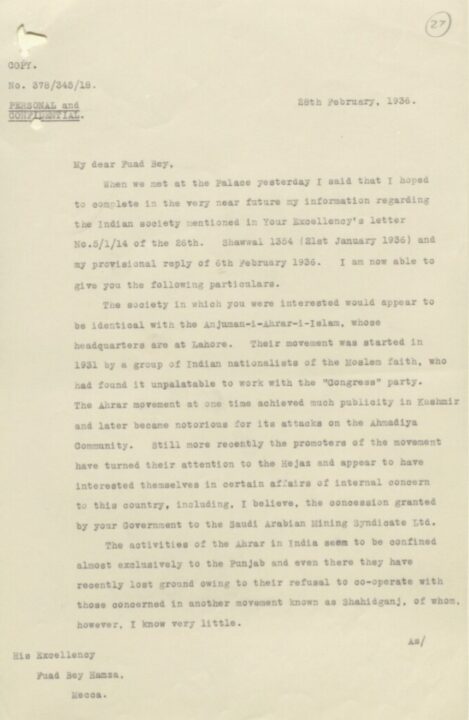

In light of this note, Sir Ryan wrote to Fuad Bey Hamza on 28 February 1936 and stated:

“The society in which you were interested would appear to be identical with the Anjuman-i-Ahrar-i-Islam, whose headquarters are at Lahore. Their movement was started by a group of Indian nationalists of the Moslem faith, who had found it unpalatable to work with the ‘Congress’ party.

“The Ahrar movement at one time achieved much publicity in Kashmir and later became notorious for its attacks on the Ahmadiya Community. Still more recently the promoters of the movement have turned their attention to the Hejaz and appear to have interested themselves in certain affairs of internal concern to this country […].

“The activities of the Ahrar in India seem to be confined almost exclusively to the Punjab and even there they have recently lost ground owing to their refusal to co-operate with those concerned in another movement known as Shahidganj, of whom, however, I know very little.” (Ibid, [27r] (54/504), British Library: India Office Records and Private Papers, IOR/L/PS/12/2077, in Qatar Digital Library, www.qdl.qa [accessed 22 September 2023])

Hazrat Musleh-e-Maud’sra poem about the Ahrars

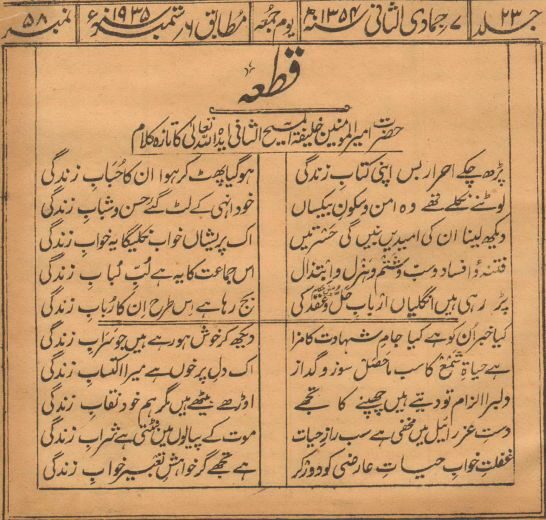

In September 1935, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra wrote a poem in which he described the true image of the Ahrars and mentioned that despite their utmost efforts, they had failed to cause any harm to Ahmadiyyat and that their only objective was to create disorder and chaos. The first four verses of this poem are as follows:

پڑھ چکے احرار بس اپنی کتابِ زندگی

ہو گیا پھٹ کر ہوا ان کا حبابِ زندگی

لوٹنے نکلے تھے وہ امن و سکونِ بیکساں

خود انہی کے لٹ گئے حسن و شبابِ زندگی

دیکھ لینا ان کی امیدیں بنیں گی حسرتیں

اک پریشاں خواب نکلے گا یہ خوابِ زندگی

فتنہ و افساد و سبّ و شتم و ہزل و ابتذال

اس جماعت کا یہ ہے لُبِّ لُبابِ زندگی

“The Ahrars have now completed their lifetime; the bubble of their life has burst into the air. They desired to snatch away the peace and ease of the weak ones; instead, their own life’s peace and happiness have gone away. You will surely witness that their desires will remain unfulfilled and their dreams will turn into nightmares. This group, in a nutshell, is disorder, chaos, oppression, abusive language and immorality.” (Al Fazl, 6 September 1935, p. 1)

In response, Maulvi Mazhar Ali Azhar wrote a poem and used extremely abusive and disrespectful language. In fact, he portrayed the true face of the Ahrar, as narrated by Huzoorra in his poem. (Al Fazl, 12 September 1935, p. 4)

Ahrar’s hesitance in accepting the mubahala challenge

The Ahrars were spreading false notions against Ahmadiyyat and attributing certain beliefs to the Jamaat. When this act of theirs went out of bounds, Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra challenged the Ahrar for a mubahala (prayer duel) during his Friday Sermon on 30 August 1935. (Al Fazl, 3 September 1935, p. 6). Mentioning this whole episode, Huzoorra wrote an article that was published as a tract on 30 October 1935:

“For a long time, the office-bearers of Majlis-e-Ahrar and their missionaries have been raising various false allegations against Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya, and misleading the people who are not aware of the true facts. For instance, they are saying that, God forbid, the Founder of the Ahmadiyya Community [Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian, the Promised Messiahas] has disrespected the Holy Prophetsa and considers himself superior to him, and that Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya holds the same belief. In the same way, they are alleging that, in view of the Promised Messiahas, [God forbid] Qadian has superiority over Mecca al-Mukarramah and Medina al-Munawwarah, and that the Ahmadis hold the same belief as well. […] When such misattributions from the Ahrar crossed all bounds, and they did not mend their ways despite continuously calling their attention, I issued a challenge to the Ahrar.” (Majlis-e-Ahrar ka mubahala ke mut’alliq na-pasandidah rawaiyyah, Anwar-ul-Ulum, Vol. 14, p. 27)

After this, Huzoorra formed a committee of some members of the Jamaat and instructed them to inform the Ahrar leaders through letters, stating all the conditions of the mubahala. Ahrar did not respond to those letters, and there was no response in regard to the conditions of the mubahala as proposed. However, after some time, on 14 October 1935, Maulvi Mazhar Ali Azhar sent a telegram to Huzoorra and said that the mubahala would take place on 23 November 1935. Huzoorra instructed Nazir Da’wat-o-Tabligh to reply to the telegram and ask Mazhar Ali Azhar as to why he did not state their view on the proposed conditions. The Ahrar did not respond to that question either and hesitated to respond directly to the Jamaat in written form so as to settle the terms and conditions of mubahala. However, they were announcing through newspaper articles, for instance in Mujahid, that they were ready for the mubahala and all conditions were accepted.

In this regard, Huzoorra said:

“If, in reality, Ahraris have accepted all of these conditions, why are they not responding in written form, since a response in the newspaper cannot be deemed a responsible reply. Due to the fact that the initial challenge is not termed a formal proceeding, it can be published in newspapers; however, the settlement of the terms and conditions should necessarily be done in writing along with the signatures of both parties.” (Ibid., p. 29)

Despite the above-mentioned article from Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra, there was no appropriate response from the Ahrar, and therefore, Huzoorra wrote another article and said:

“On 30 October 1935, I had published a poster and tract entitled ‘Majlis-e-Ahrar ka mubahala ke mut’alliq na-pasandidah rawaiyyah’ [Inappropriate response from Ahrar in relation to the mubahala]. I hoped that after this announcement, Majlis-e-Ahrar would mend its behaviour and incline towards a serious discussion about the mubahala, however, regretfully, in contrary to my hope, Majlis-e-Ahrar has made its behaviour even worse, and instead of adopting the correct method, they are committing alterations of facts. […]

“Mr Mazhar Ali Sahib has stated in Chiniot that ‘I went to Qadian and told that the mubahala should take place in Qadian and on the truthfulness of Mirza Sahib [the Promised Messiahas], and Mirza Mahmud has accepted it.’ (Mujahid, 6 November 1935, p. 2)

“Further in this regard, the sajjada nasheen of Alo Mahar, Syed Faiz-ul-Hassan Sahib has stated during his speech in Chiniot:

“‘Mirza Mahmud has challenged the Majlis-e-Ahrar to do a mubahala with him at Qadian on the prophethood of Mirza [Sahib]. The leaders of Ahrar have accepted this challenge.’ (Ibid)

“However, the fact is that I had given a challenge to the Ahrar to do a mubahala in Lahore or Gurdaspur, on the allegations of Ahrar that [God forbid] the Founder of the Ahmadiyya Community and Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya gives higher status to Mirza Sahib than the Holy Prophetsa and that they disrespect him. Upon this, I came to know that the Ahrar said that a mubahala should also happen in Qadian on the truthfulness of the Founder of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. In response, I wrote that if they wish to do a mubahala on the truthfulness as well, then let it be, but that mubahala should be separate from the one on the allegation of giving higher status to the Founder of the Ahmadiyya Community than the Holy Prophetsa. And in regards to Qadian, I wrote that if Ahrar have any specific reservations concerning Lahore or Gurdaspur [where the mubahala on the allegations was supposed to be held], they can come to Qadian. Now, everyone can understand that the president of the Ahrar Conference has lied during his Chiniot speech.” (Ahrar Khuda Ta’ala ke khauf se kaam letay huay mubahala ki sharait tay karein, Anwar-ul-Ulum, Vol. 14, pp. 37-39)

Huzoorra went on to narrate the reason behind Ahrar’s hesitation and said:

“The truth of the matter is that the government did not allow Ahrar to hold their conference in Qadian this year. When they read my mubahala challenge, they thought, ‘Well, we will see what to do about the mubahala, we will benefit from the opportunity and hold a conference in Qadian without confronting the Government, because the mubahala challenge is from Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya, and we will go there on their invitation, and the Government would not stop us.’ Thus, keeping in mind this point, they decided to accept the mubahala without bringing the terms and conditions into written form. Hence, due to the fact that the conditions would be undecided, various points could be raised on the spot in order to reject the mubahala. Meanwhile, in this way, they would have the opportunity to hold a conference in Qadian.” (Ibid., pp. 42-43)

Meanwhile, the Ahrar were mobilising their masses and appealing to them to gather in Qadian on 22 and 23 November for a conference:

“Sheikh Bashir Ahmad, President of the All-India National League, referring to the challenge for a ‘prayer ordeal’ issued by the Head of the Ahmadiyas of Qadian, says that the Ahrars have not accepted the challenge on the terms stipulated, but that they are preparing to assemble in Qadian on this pretext.” (The Civil and Military Gazette, 14 November 1935, p. 5)

On 21 November 1935, Huzoorra wrote another article and mentioned that the Ahrar were spreading lies by announcing that ‘We have accepted the mubahala challenge, but Imam Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya is hesitating from accepting it.’

In this article, Huzoorra refuted this false notion in light of the true facts, narrated the whole episode, and stated what the actual objective of the Ahrar was. (Kiya Ahrar waqe’ie mein mubahala karna chahtay hain?, Anwar-ul-Ulum, Vol. 14, pp. 53-61)

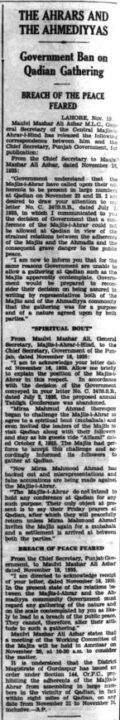

Government bans Ahrar from holding the conference

The Ahrar requested the government for permission to hold a conference in Qadian, however, the response was as follows:

“From the Chief Secretary, Punjab Government, to Maulvi Mazhar Ali Azhar, dated November 18, 1935.

“‘I am directed to acknowledge receipt of your letter, dated November 18, 1935. In the present state of the relations between the Majlis-i-Ahrar and the Ahmadiyya community, Government must regard any gathering of the nature and on the scale contemplated by you as likely to lead to a breach of the public peace. They cannot, therefore, alter their attitude to such a gathering.’ […] It is understood that the District Magistrate of Gurdaspur has issued an order under Section 144, Cr.P.C., prohibiting the adherents of the Majlis-i-Ahrar from assembling in large numbers in the vicinity of Qadian, in fact, within eight miles of Qadian, on any date from November 21 to November 24, inclusive.” (The Civil and Military Gazette, 20 November 1935, p. 4)

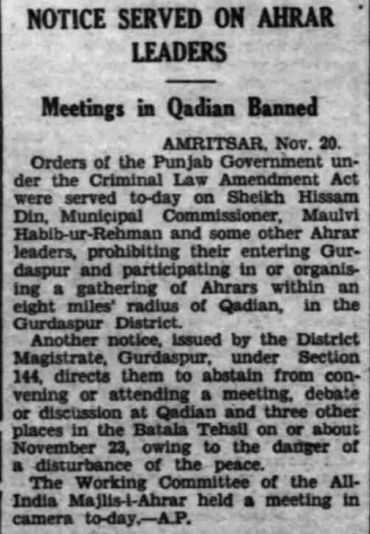

On 20 November 1935, the Government issued a notice to the Ahrar leaders to inform them about the ban on any gathering in Qadian:

“Orders of the Punjab Government under the Criminal Law Amendment Act were served today on Sheikh Hissam Din, Municipal Commissioner, Maulvi Habib-ur-Rehman and some other Ahrar leaders, prohibiting their entering Gurdaspur and participating in or organising a gathering of Ahrars within an eight miles’ radius of Qadian, in the Gurdaspur District. Another notice, issued by the District Magistrate, Gurdaspur, under Section 144, directs them to abstain from convening or attending a meeting, debate or discussion at Qadian and three other places in the Batala Tehsil on or about November 23, owing to the danger of a disturbance of the peace.” (The Civil and Military Gazette, 21 November 1935, p. 5)

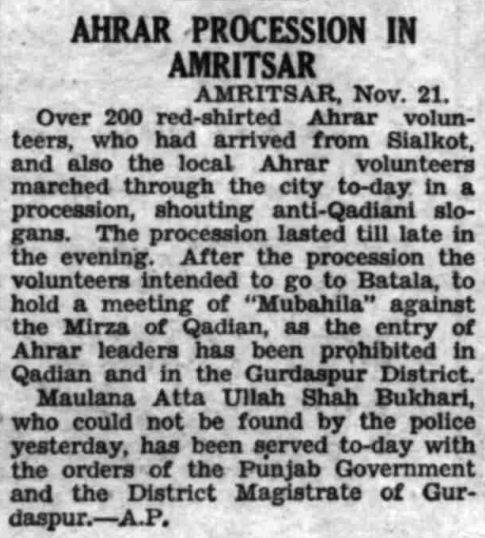

Ahrar procession in Amritsar

On 21 November 1935, the members of Majlis-i-Ahrar gathered in Amritsar and held an anti-Ahmadiyya procession, where they shouted anti-Ahmadiyya slogans. “After the procession the volunteers intended to go to Batala, to hold a meeting of ‘Mubahila’ against the Mirza of Qadian, as the entry of Ahrar leaders has been prohibited in Qadian and in the Gurdaspur District.” (The Civil and Military Gazette, 23 November 1935, p. 18)

Call for even greater sacrifices

The Civil and Military Gazette reported on 26 November 1935, “Information has been received here that Friday prayers [on 22 November] at Qadian were held peacefully. Ahmadis from every centre assembled in response to the appeal made by the President of the National League. In consequence of the order issued by the District Magistrate of Gurdaspur, prohibiting Ahrars from assembling within eight miles of Qadian, Ahrars did not go to Qadian. The Friday sermon was delivered by Hazrat Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad, the head of the community. He exhorted Ahmadis ‘to be prepared to make even greater sacrifices in the following year.’”

Ahrar’s inflammatory efforts

Janbaz Mirza falsely alleges that in December 1935, “the government announced Section 144 in Qadian upon the behest of” Ahmadis, just to prevent any outsider Muslim from offering Jumuah prayer in Qadian. Obviously, this order was an interference in religion. The Ahrar decided to disobey this order.” (Karwan-e-Ahrar, Vol. 1, 1975, Maktabah Tabsarah, Lahore, pp. 57-58)

He further states:

“While on the way to Qadian,” Syed Ataullah Shah Bukhari “was arrested between Batala and Qadian; however, I somehow reached Qadian and offered the Jumuah prayer at the ‘Beri Wali Masjid’”, and “addressed the local Muslims who had gathered for the prayer and made them aware of the mutual connections between the [British] Government and the” Ahmadis. “For the coming Jumuah, Maulana Abul Wafa Shahjahanpuri was to visit Qadian, and I was instructed by the Jamaat [Ahrar] to accompany Maulana up to Batala. Since I had been to Qadian a week ago, the government handed a notice to me also along with Maulana Abul Wafa at the Batala Railway Station, stating that I could not enter Qadian. However, I ripped off the notice and prepared to go to Qadian along with Maulana. Upon entering the marked boundary, both of us were arrested by the police. On the same day, the court gave both of us three-month imprisonment, a 50 rupee fine, and one month of further imprisonment in case of non-payment of fine. […] Upon reaching the Gurdaspur Jail, we met Shah Ji. After some days, both of the elders were transferred to another jail, and I was alone there. However, the next Friday, Maulana Qazi Ahsan Ahmed joined me.” (Ibid., p. 58)

Narrating this incident with more details, he wrote under the heading “Ahrar ki Qadian mein Civil Naa-Farmani” – Ahrar’s Civil Disobedience in Qadian:

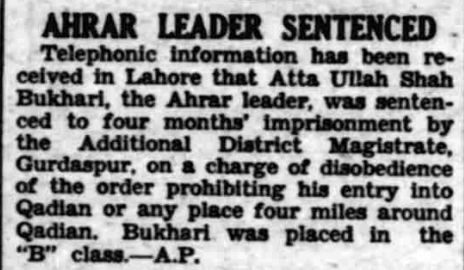

“In response to the government’s decision that Ahrar could not enter Qadian, Ahrar leaders decided to disobey this order,” and that “Syed Ataullah Shah Bukhari will lead the Jumuah prayer in Qadian on 6 December [1935] and then return. If the government interfered, it would be considered a ban on Jumuah [prayer], thus, Ahrar would take it as interference in religion, and initiate a movement in response.” Hence, “Syed Ataullah Shah Bukhari departed from Amritsar on the morning of 6 December, and upon reaching the Batala station, the government wanted to stop him from entering Qadian through a notice. However, according to the party’s order, he proceeded towards Qadian.” The “police were also aboard the same railcar where Shah Ji was sitting. As soon as the train reached Jaintipur railway station, the police inspector went to Shah Ji and said that ‘beyond this will be the disobedience to Section 144. Thus, you must get off at this very place.’ However, Shah Ji refused to obey this police order and continued the journey. At last, police arrested him.” (Karwan-e-Ahrar, Vol. 2, 1977, Maktabah Tabsarah, Lahore, p. 302)

Ataullah Shah Bukhari was sentenced to four months’ imprisonment by the Additional Magistrate, Gurdaspur, on a charge of “disobedience of the order prohibiting his entry into Qadian or any other place four miles around Qadian. Bukhari was placed in the ‘B’ class.” (The Civil and Military Gazette, 8 December 1935, p. 7)

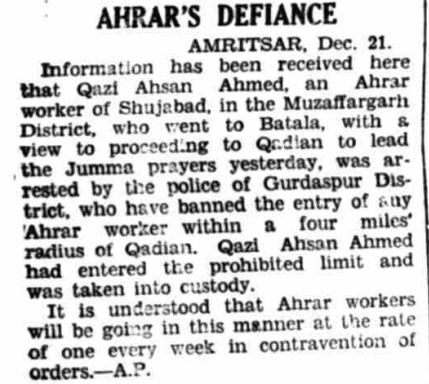

On 21 December 1935, a member of the Ahrar from Shujabad, Qazi Ahsan Ahmed, went to Batala with a view to proceeding to Qadian to lead the Jumuah prayer there. He was arrested by the police of Gurdaspur District since they had banned the entry of any Ahrar worker within a four miles’ radius of Qadian. Qazi Ahsan Ahmed had entered the prohibited limit and was taken into custody. “It is understood that Ahrar workers will be going in this manner at the rate of one every week in contravention of orders.” (The Civil and Military Gazette, 22 December 1935, p. 6)

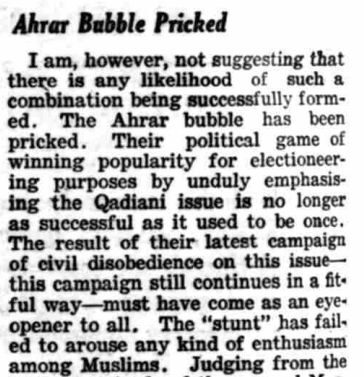

‘Ahrar Bubble Pricked’

The Civil and Military Gazette wrote on 22 December 1935, “The Ahrars have so far never cared to have a constructive programme. ‘Down with the Qadianis!’ appears to be the be-all and end-all of their political creed. This cry, by arousing religious feelings among Muslim masses, may ensure the Ahrars a certain number of votes during the elections, but it is obvious that this cry cannot form the political programme of any party in the Council. […] The Ahrar bubble has been pricked. Their political game of winning popularity for electioneering purposes by unduly emphasising the Qadiani issue is no longer as successful as it used to be once.”

Ahrar’s demand from Muslim Anjumans

On 31 January 1936, “Majlis-e-Ahrar demanded from all Muslim Anjumans [societies] from all over India to expel” Ahmadis “from their institutions.” When the Anjuman Himayat-e-Islam did not expel the Ahmadi members, the Ahrar made a desperate move and “presented a resolution on behalf of the public, at the annual Jalsa of the Anjuman Himayat-e-Islam,” demanding that the Ahmadis “must be expelled from the Anjuman immediately, since they are non-Muslims, and a non-Muslim cannot be a member of the Anjuman Himayat-e-Islam. Upon this resolution, there was a bit of a hue created; however, at last, the resolution was passed.” (Karwan-e-Ahrar, Vol. 2, 1977, Maktabah Tabsarah, Lahore, pp. 328-329)

Ahrar’s demand from Jinnah

In 1936, some Ahrar leaders had a meeting with Mr Jinnah in Lahore, in which they offered him their support in the upcoming Provincial elections on one condition that the doors to join the Muslim League would be closed for Ahmadis. Upon this, Jinnah said that this decision can only be made by the All-India Muslim League. (Karwan-e-Ahrar, Vol. 2, 1977, Maktabah Tabsarah, Lahore, pp. 372-273)

An attack

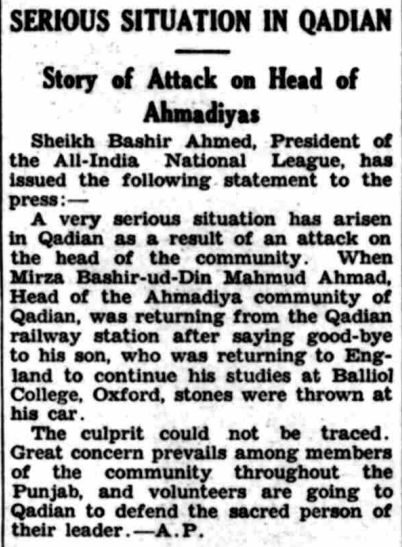

On 17 September 1936, when Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra was returning from the Qadian railway station after saying goodbye to Hazrat Sahibzada Mirza Nasir Ahmadrh who was going back to England for his studies, an opponent threw a stone at the car of Huzoorra. However, by the grace of Allah, Huzoorra remained unharmed. (Al Fazl, 19 September 1936, p. 2)

Reporting on this, The Civil and Military Gazette wrote on 20 September 1936, under the heading “Serious Situation in Qadian”:

“Sheikh Bashir Ahmed, President of the All-India National League, has issued the following statement to the press:

“‘A very serious situation has arisen in Qadian as a result of an attack on the head of the community. When Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad, Head of the Ahmadiya community of Qadian, was returning from the Qadian railway station after saying goodbye to his son [Hazrat Sahibzada Mirza Nasir Ahmadrh], who was returning to England to continue his studies at Balliol College, Oxford, stones were thrown at his car.

“‘The culprit could not be traced. Great concern prevails among members of the community throughout the Punjab, and volunteers are going to Qadian to defend the sacred person of their leader.’”

On 29 September 1936, the Ahrars held a conference in Sialkot, where “Maulana Habib-ur-Rehman Ludhianvi said that they had determined to oppose the Ahmedyas and to secure freedom.” (The Civil and Military Gazette, 2 October 1936, p. 7)

Anti-Ahmadiyya propaganda in Ahrar’s electoral manifesto

In their manifesto for the upcoming Provincial elections of 1936-37, which was in fact a speech of Chaudhry Afzal Haq, they also included hateful propaganda against Ahmadiyyat, which stated:

“It is the duty of every patriot person to remain aware of the plans of this ‘enemy’ of the country. I expect from the Islamic communities of the country, in addition to the political parties, that they should keep an eye on” the “activities of this ‘enemy’ of the Muslim world. They pretend to be friends but are the enemies of the Muslims. […] Due to the full encouragement from the Government, they pose themselves as Muslims and are very swiftly seizing the rights of the Muslims.” (Karwan-e-Ahrar, Vol. 2, 1977, Maktabah Tabsarah, Lahore, p. 451)

In this manifesto, they also declared Ahmadis to be the “enemies” of the Holy Prophet Muhammadsa.

The only purpose behind such false and hateful propaganda against Ahmadiyyat was to get some sympathy from the Muslim community during the elections; however, despite all these desperate moves, “Majlis-e-Ahrar faced a huge defeat in Punjab and other provinces.” (Ibid., p. 495)

A failed ‘prediction’ of Chaudhry Afzal Haq

Mentioning the Ahrar’s efforts against Ahmadiyyat, during the All-India Ahrar Conference at Peshawar in April 1939, Chaudhry Afzal Haq, known as the Mufakkir-e-Ahrar, made the following statement:

“We have faith in the mercy of God that the vast system of the Ahrar will, despite financial difficulties, definitely eradicate this ‘fitna’ within ten years’ time.” (Khutbat-e-Ahrar, Vol. 1, compiled by Agha Shorish Kashmiri, Maktaba-e-Ahrar, Lahore, 1944, p. 37)

The early part of this article has narrated the details in light of facts as to how the Ahrar’s activities caused unrest and chaos in British India in general and within the Muslim community in particular. So, the history is clear on this point that Ahrars were the real fitna of that time.

As far as the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat and its progress is concerned, after 84 years of his ‘prediction’, I would like to let the readers assess the validity of his ‘prediction’.

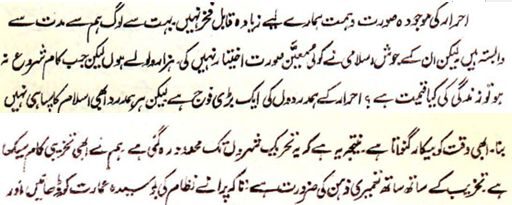

In another instance, Chaudhry Afzal Haq states:

“Ahrar’s current condition and [the level of] determination does not make us proud at all. There are many who have been associated with us for a very long time; however, their passion for Islam has not taken any significant shape. Regardless of how great the passion is, what is the significance of one’s life if they do not begin to make [practical] efforts? There is a huge army of Ahrar’s sympathisers; however, each of those sympathisers has not become a soldier of Islam. Right now, they are wasting their time, and for this reason, this movement is now limited to cities alone. By now, we have learnt destructive work; a constructive mindset is also required along with a destructive one.” (Tarikh-e-Ahrar, Maktaba-e-Majlis Ahrar-e-Islam Pakistan, 1968, pp. 260-261)

Ahrar’s internal dilemmas

Professor Dr Muhammad Khurshid and Professor Dr Muhammad Akbar Malik, both from the Department of Pakistan Studies at the Islamia University Bahawalpur, have concisely described Ahrar’s internal dilemmas:

“The Ahrar often acted imprudently,” and “their leaders did not care for the public sentiments in certain locations and created resentment against themselves by speaking unnecessarily against popular religious and spiritual personalities, highly venerated by the local people.” The Ahrar “had always been facing a paucity of funds.” Towards the end of 1932, “the Ahrar organ Hurriyat had to discontinue its publication due to non-availability of funds.” Next year, the Ahrar were “reported to be in a deplorable financial position, which continued to be so till the Quetta earthquake when the Ahrar leaders appealed to the public to give contributions to the Ahrar for relief work instead of contributing to the Government. How people gradually became reluctant to give contributions to the Ahrar? It is well demonstrated by the fact that on the occasion of Eid at Lahore, the Ahrar could collect only an amount of Rs. 41 from a gathering of more than 40,000 Muslims. […] One possible reason for failure of the Ahrar in collection of contributions from the public was the frequent charges of embezzlement of funds.”

They further state:

“In 1932, on at least three occasions, apprehensions were raised regarding the funds etc. In Sialkot, the Secretary of the Majlis filed a suit against the treasurer accusing him of embezzlement. In July, Zain-ul-Abdin Shah, the president of Multan branch resigned and refused to render an account of the funds at his disposal. There were instances of stealing the property of the organization by responsible workers of the Majlis. The Manager of Hurriyat, Hussain Mir, was dismissed on the charges of stealing 250 reams of newsprint. Sometimes, the Ahrar workers were found guilty of stealing petty office goods and misappropriating cash from the office of the organization. Janbaz Mirza, General Secretary Majlis-i-Ahrar Amritsar, was accused by his Ahrar friends of stealing Rs. 300 from the Ahrar office and he resigned from [the] secretary-ship. There was a split again among the Lahore and Sialkot Ahrar in March 1933, and the Ahrar Leaders were accused of misappropriating funds and not accounting for expenditure. Next year the Jullundur Muslims accused Ahrar leaders of accepting bribe from Kapurthala state authorities and of embezzlement of funds collected for propaganda purposes.” (The Political Activities of Majlis-i-Ahrar: A Critical Study, Pakistan Annual Research Journal, 2015, pp. 44-45)

Pakistan: Ahmadis and Ahrar

While much has been written on Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya’s support for the Indian Muslims and its role in the formation of Pakistan, and readers can find various Al Hakam articles on this topic as well, let us shed some light on the Ahrar’s opposition to the Muslim League and the formation of Pakistan.

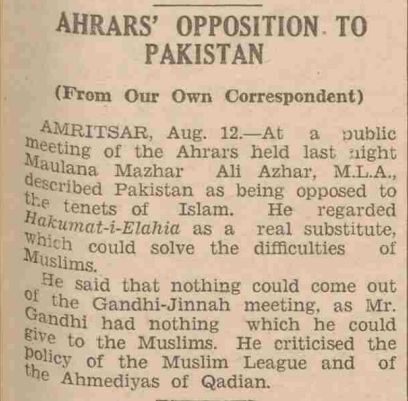

The Civil and Military Gazette wrote under the heading “Ahrar’s Opposition to Pakistan”:

“At a public meeting of the Ahrars held last night, Maulana Mazhar Ali Azhar, M.L.A., described Pakistan as being opposed to the tenets of Islam. He regarded Hakumat-i-Elahia as a real substitute, which could solve the difficulties of Muslims.” Moreover, “he criticised the policy of the Muslim League and of the Ahmediyas of Qadian.” (The Civil and Military Gazette, 13 August 1944, p. 5)

Mentioning the Ahrar’s support for the Indian National Congress in the non-cooperation movement and their opposition to the creation of Pakistan, Muhammad Jalaluddin Qadri states:

“‘The supporters of the non-cooperation’ interpreted and inferred the Quranic verses and Ahadith of the Prophetsa in accordance with the ‘policy of Gandhi’. We are unaware as to under the influence of which magic of trust, Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind and Majlis-e-Ahrar-e-Islam cooperated with the Congress in its ideology of ‘Nationalism’ that was based on unacquaintance of the Faith. […]

“An active volunteer of the Pakistan Movement, former MPA Sheikh Muhammad Saeed (of Jhang), writes in his memoirs in relation to the Majlis-e-Ahrar:

“‘Majlis-e-Ahrar and nationalist Muslims, under the leadership of Chaudhry Afzal Haq, Maulana Habib-ur-Rahman Ludhianvi, Mian Hassamuddin, Syed Ataullah Shah Bukhari, Maulana Dawood Ghaznavi, and the survivors of Maulana Sanaullah Amritsari, staunchly stood in opposition to the Pakistan Resolution. Majlis-e-Ahrar, which was in fact a branch of the Jamiat [Ulema-e-Hind], now openly came forward in opposition to [the creation of] Pakistan.’ (Mushkilat-e-Laa-Ilaah, Faisalabad, 1981, p. 56).” (Khuli Chitthi Banaam Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind wa Majlis-e-Ahrar-e-Islam [Taqdim by Muhammad Jalaluddin Qadri], Maktaba-e-Rizwiyyah, Lahore)

The Munir Inquiry Report stated:

“Though they had cut themselves off from the Congress, the Ahrar continued to flirt with that body right up to the Partition. One of the resolutions passed by the Working Committee of the Majlis-i-Ahrar which met at Delhi on 3rd March, 1940, disapproved of the Pakistan plan, and in some subsequent speeches of the Ahrar leaders Pakistan was dubbed as ‘Palidistan’. […] In the resolution passed by the Punjab Provincial Ahrar Conference held at Gujranwala from 17th to 19th March 1943, and in a subsequent resolution passed at Saharanpur in the same year they declared themselves against the proposed Partition which they described as vivisection of the country.” (Report of the Court of Inquiry constituted under Punjab Act II of 1954 to enquire into the Punjab Disturbances of 1953, 1954, p. 11)

It further states:

“The Partition of 1947 and the establishment of Pakistan came as a great disappointment to the Ahrar because all power passed to the Congress or the Muslim League, and no scope for activity was left for the Ahrar in India or in Pakistan. The new Muslim State had come to them as a shock, disillusioned them of their ideology and finished them as a political party.” (Ibid, p. 12)

It is stated in the Encyclopedia Pakistanica:

“In cooperation with the Congress, Majlis-e-Ahrar staunchly opposed the Muslim League and the creation of Pakistan until the general elections of 1946. Following the formation of Pakistan, general Ahrar accepted the reality; however, some of their leaders did not accept it from the heart. As a result, in order to get control over the unlawfulness and rebellion-like situation in its political activities, the Government of West Pakistan banned this Party on 27 June 1957. Since none of their pioneer leaders were alive at the time, thus, general volunteers did not take the path of protest. However, they diverted the attention of their efforts with greater fervour in favour of the Khatam-e-Nabuwwat movement, which was being run against” Ahmadiyyat. (Encyclopedia Pakistanica, Syed Qasim Mahmud, Al Faisal, p. 164)

Conclusion

The Ahrar, having a confused ideology, harboured sentiments of hate against the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community and, hence, faced a huge downfall.

On the other hand, Tahrik-e-Jadid, the scheme launched by Hazrat Musleh-e-Maud, Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra, in response to the Ahrar’s onslaught on Ahmadiyyat, is continuing to bear fruits. Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya has been able to build hundreds of mosques around the world, translate the Holy Quran into multiple languages, defend the teachings of Islam amidst harsh attacks by anti-Islam movements, and take the message of Islam to the corners of the world.