Asif M Basit

Little is known about the magnificent life that Hazrat Hakim Maulvi Nuruddinra (Hazrat Nuruddinra henceforth) led before becoming acquainted with the Promised Messiahas and, subsequently, moving to Qadian. The only information available is through fragmented memoirs that Hazrat Nuruddinra wrote for Hakim-e-Haziq (edited and published by Hakim Muhammad Hussain, alias Marham-e-Isa) or narrated to Akbar Shah Najibabadi – the latter recorded and published as Mirqat al-Yaqin. (www.alislam.org/urdu/pdf/MirqatulYaqeen.pdf)

What was later recorded of this phase of his life in Hayat-e-Nur and Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyyat was derived from the above two sources with very few exceptions. I must, however, credit the great work done by the authors and editors of these works as they had little or no access to material that could take them through the annals and alleyways that have been available to the author of this article – albeit with great difficulty, still. I must, right at the outset, pay tribute to their works that provided a stepping-stone for delving deeper into the magnificent life of the great man, before he got to be known as a great man.

As the brief insight into his formative years is based on his own narrations, his humility seems to have shrouded the splendour of this phase. The years that followed – as a companion and then successor of the Promised Messiahas – were recorded by Ahmadiyya press and literature and presented in full light.

Any difference of opinion with the above-mentioned great biographical accounts should not be seen as disrespect, for research is a valley with many paths descending and ascending in and out of it. Years to come will bring to light new sources and the opinions of researchers could continue to differ.

Early years

Born in c. 1841 in Bhera – a small town in the British Punjab – Hazrat Nuruddinra had around him a family with great love for knowledge. Hazrat Nuruddinra reminisced his father saying: “Head in pursuit of knowledge to such distant lands where news of the death of your mother and mine does not reach you!”(Mirqat al-Yaqin)

It is important to note here that the concept of education in British Indian Muslims had evolved around their identity which was undergoing a serious crisis. It was a time past the twilight of Muslim glory in the Islamic world in general, and India in particular, where a Muslim empire had recently fizzled before a mighty colonial power.

In an attempt to reconstruct Muslim identity, religious education was seen as the only way forward. (Muhammad Tayyib, Dar al-Ulum Deoband, Dar al-Isha‘a, Deoband, 1965; Ziaul Haque, Muslim Religious Education in Indo-Pakistan, Islamic Studies, Vol. 14, Issue 4, Islamic Research Institute, International Islamic University, Islamabad)

What constituted as education was restricted to the Holy Quran, hadith (along with their exegetist commentaries) and languages that could facilitate both – mainly Arabic and Persian.

Architecture had been the flagship of most Islamic sultanates but it was not the type of knowledge that could be imparted by ulema and, thus, required specialised professionals. However, what glorified these grand structures was calligraphy, the art of which could be disseminated relatively easily; hence earning the outlook of an Islamic discipline.

Tibb-e-Yunani (Eastern Medicine) was another discipline that had been grouped with Islamic education and was pursued by many but specialised in by those looking to further their career in this field.

It was in this atmosphere that the young Hazrat Nuruddinra set out to acquire knowledge – a long journey that turned him into a student-traveller.

Hazrat Nuruddinra recalls his first journey in this pursuit to be of Lahore in 1270 AH (1853 CE), at the age of around 12. Through his statement about this journey, his brother, Sultan Ahmad, appears to have owned or co-owned a printing press namely Matba Qadria Press, in the Kabli Mal vicinity of Lahore.

(Dost Muhammad Shahid Sahib, in Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyyat, asserts that Sultan Ahmad ran this printing press in Lahore. Records dating back to 1880 suggest that it was owned by a Munshi Qadir Bakhsh. A periodical on Eastern medicine, namely Takmil al-Hikmah, carries the name of the press and its owner in the credit line on the title page as: Matba Qadri Press Lahore ba-ehtimam Munshi Qadir Bakhsh ke chhapa. So, Sultan Ahmad’s involvement was either as a co-owner or in some other managerial position.)

Sultan Ahmad’s connection to Lahore, as well as this journey, was in connection to affairs relating to this press.

Having arrived at Lahore, Hazrat Nuruddinra suffered from diphtheria and was treated by Hakim Ghulam Dastgir Lahori who had a clinic in the Syed Mittha area. It was at this point that he first developed an interest in tibb-e-Yunani, although his education in this field did not start at this point. His brother thought it more appropriate that he be taught the Persian language and calligraphy. For the former, he was given in the pupillage of Munshi Muhammad Qasim Kashmiri and to Imam Verdi for the latter. Both the tutors were of very high repute, with Imam Verdi being described as such by historians of the art of Muslim calligraphy:

“In the region of what is now Pakistan, a great contribution was made by Imam Verdi who came from Iran to Kashmir and from there was brought to Lahore by the Muslim Governor of the Sikh rulers named Imamuddin. At this time between 1860 and 1870, Col. Holroyd was the Director of Education in Lahore and he wanted to widely popularise the art of calligraphy. Imam Verdi however, like the old masters, did not believe in revealing the secrets of his art to any but his pupils. However, one of Imam Verdi’s pupils, Sayyid Ahmad, took to Col. Holroyd all the exercises that were given to him as lessons by Imam Verdi. Col. Holroyd got them printed and put on sale so that everyone might benefit from them. Imam Verdi’s work can be seen in the Lahore Museum and on Sutar Masjid which he got built himself.” (S Amjad Ali, Calligraphy in Indo-Pakistan, in The Proceedings of the Hijra Celebration Symposium on Islamic Art, Calligraphy, Architecture and Archaeology)

Another work on the topic suggests:

“It is important to consider the work of Imam Verdi because he was the last most acknowledged master, and can be considered the book end, of Iranian Nastaliq in Lahore. At the culmination of the half century that followed his demise, Iranian Nastaliq itself came to an end in Lahore. It is fair to say that the two centuries long dominance of Iranian Nastaliq that began with Daylami was concluded with Imam Verdi.”(Seher A Shah, A History of Traditional Calligraphy in Post-Partition Lahore, MA thesis for The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University, 2016)

With such glorious beginnings, Hazrat Nuruddin’sra educational career was to reach great heights. Although, not having a disposition for both areas, he could not benefit much from his tutors in Persian and calligraphy; but his stay of around two years in Lahore kindled in his heart the love for the study of medicine. This interest – initially acquired from his physician Hakim Ghulam Dastagir Lahori – developed when he got acquainted with Hakim Allahdin Lahori; the latter trained by the former in the field of tibb. Both these hakims were of great repute and have been mentioned by Kanhaia Lal in Tarikh-e-Lahore with much esteem. It was through conversations with Hakim Allahdin Lahori that Hazrat Nuruddinra gained basic knowledge of tibb-e-Yunani. He returned to Lahore in c. 1855.

According to Kanhaia Lal, most books on Islamic knowledge were published in Delhi and Lucknow and then distributed all over India. For the love of knowledge, the family of Hazrat Nuruddinra must have had many booksellers as friends. This is understood when he narrates about two booksellers coming to stay at their place: A Muhammad Amin from Lucknow is credited with introducing him to the translation of the Holy Quran, and another bookseller from Bombay for providing him Taqwiat al-Imaan and Mashariq al-Anwar.

This reading seems to have set the scene for Hazrat Nuruddin’s strong bonding with the Ahl-e-Hadith version of Islam, to which he remained devotedly attached for many decades to follow. That the booksellers were staunch Ahl-e-Hadith becomes evident where Hazrat Nuruddinra mentions them as vehicles of funds sent off to the Mujahidin fighting on the North Western Frontier.

After a short while, Hazrat Nuruddinra was back in Lahore and under the tutelage of Hakim Allahdin Lahori again. This episode of learning tibb was to be short-lived and he returned to Bhera, from where he was sent to study at a secular school at Rawalpindi. He notes this to be in c. 1858 and at the age of “almost eighteen”.(Mirqat; Hakim-e-Haziq)

The youth years

During his stay at Rawalpindi, Hazrat Nuruddinra mastered himself in the disciplines of mathematics and geography and attempted the tahsili imtihan (district level examination) – a competitive test to enter the government’s education service. Success in this examination earned him a place as headmaster of a school in Pind Dadan Khan – a town near his hometown of Bhera.

This venture of Hazrat Nuruddinra is not something insignificant when seen in the light of the British educational policy that was unfolding in the wake of the 1857 mutiny. The British, since the times of the East India Company, had been working to devise some educational policy for Indian natives. From 1792 – when work on education policies commenced at the hand of Charles Grant – to 1830, no uniform policy had been formulated. The British educationalists were broadly split into Anglicists and Orientalists – the former stressing English as the medium of instruction, the latter on Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit. Vernacular education – which could be more productive in educating the native masses – was nowhere on the radar.

It was with Allan Macaulay’s efforts that vernacular education got to be seen as a serious issue that needed to be dealt with by the government; Charles Wood’s despatch, which came out in 1854, worked as a catalyst. Wood emphasised modern (or Western) education to be imparted, yet Oriental studies not be ignored. He placed the onus of education on the state and encouraged vernacular education. Allan Octavian Hume was to be instrumental in executing the idea of vernacular education and opening Anglo-vernacular schools – piloted in 1849 in eight districts of North Western Province and spread across India by 1856. These schools, owing to their district-scale functionality, were also known as tahsili schools. (Anu Kumar, New Lamps for Old: Colonial Experiments with Vernacular Education, Pre- and Post-1857, in Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 42, No. 19, 2007)

It was for employment at such a tahsili school that Hazrat Nuruddinra attempted and passed the examination. From what we have discussed above, and what will follow, points to the fact that his personality was a balanced blend of the oriental, vernacular and modern tendencies – three ingredients essential for socio-political awakening in native Indians.

Having served in the field of public education for four years, Hazrat Nuruddinra felt the need of acquiring further education. He resigned from his job at the Anglo-vernacular school of Pind Dadan Khan to travel to various academic centres of India. This brings us, according to the estimated timeline that he provides, to c. 1862.

Further education

Upon return to Bhera, Hazrat Nuruddinra joined the classes of Maulvi Ahmad al-Din, more commonly known as “Bugay walay qazi” for his belonging to a nearby town called Buga. Maulvi Ahmad al-Din was the younger brother of Maulvi Ghulam Mohyiuddin Bugwi – both established scholars of Islamic studies. They had lived in Delhi in the pupillage of Shah Muhammad Ishaq – the grandson of Shah Abdul Aziz Muhadith Dehlvi and great-grandson of Shah Waliullah Muhadith Dehlvi. The educational qualification of both brothers was certified by none other than Shah Abdul Aziz himself. (Faqir Muhammad Jhelumi, Hadaiq al-Hanafiyya)

This stay with Maulvi Ahmad al-Din enabled Hazrat Nuruddinra to acquire knowledge of Arabic and strengthened his affiliation with the Ahl-e-Hadith school. However, after only a year, in c. 1863, Hazrat Nuruddinra left for Lahore. He was admitted to Hakim Muhammad Bakhsh for classes in tibb, but soon decided to travel to Rampur.

This choice of travelling to and settling in Rampur was not a random one, as Rampur was then a centre of Muslim learning where scholars of renown, from the great centres of Delhi and Lucknow, had stationed themselves.

Nawab Faizullah Khan, the founder of the princely state of Rampur, had made concerted efforts to cultivate his state into a profound centre of learning. He had invited Maulana Abdul Ali Farangi Mahali to establish an educational institute and had named it Madrasah-e-Aliya. Scholars like Maulana Nur Salam Shah and Abd al-Haq Dehlvi had been taken on board. Among others, some names that stand out are those of Mullah Ghiyas-ud-Din, Fazl Haq Khairabadi, Abdul Haq Khair Abadi, Maulana Irshad Hussain – all scholars of great stature. This brought Rampur at par with the centres at Deoband, Bareilly and Lucknow. (Barbara Metcalf, Islamic Revival in British India: Deoband 1860-1900, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 1982)

Rampur attracted seekers of Islamic knowledge not only from all over India but also from other parts of the Islamic world like Afghanistan and Bukhara. (Muhammad Abdus Salam Khan, Madrasa-e-Aliya Rampur: Ek Tarikhi Darsgah, Rampur Raza Library, 2002)

His hectic and untiring schedule of learning – spanning on almost three years – made him suffer from insomnia and was left looking for the best possible hakim (physician in Eastern medicine) in the country to rid him of this misery. The one person renowned as such was Hakim Ali Hussain Lakhnavi, who was to be found, as the name suggests, in Lucknow. Putting the dotted timeline together, we can assume that Hazrat Nuruddinra left Rampur for Lucknow in c. 1866.

The primary motive behind leaving Lucknow was the search of the best known hakim in the country. Hakim Ali Hussain Lakhnavi had served as the royal physician to Nawab Yusuf Ali (d. 1865) – a ruler of the state of Rampur. Once, the Nawab was on a journey to Calcutta that Hakim Ali Hussain sent his son to Kanpur to request the Nawab to take a short break there. The Nawab honoured the invitation and this reception took place in Kanpur at the house of Maulvi Abdur Rahman Khan, proprietor of Matba-e-Nizami – one of the leading printing presses of the country. (Tazkira-e-Kamilan-i-Rampur, p. 255)

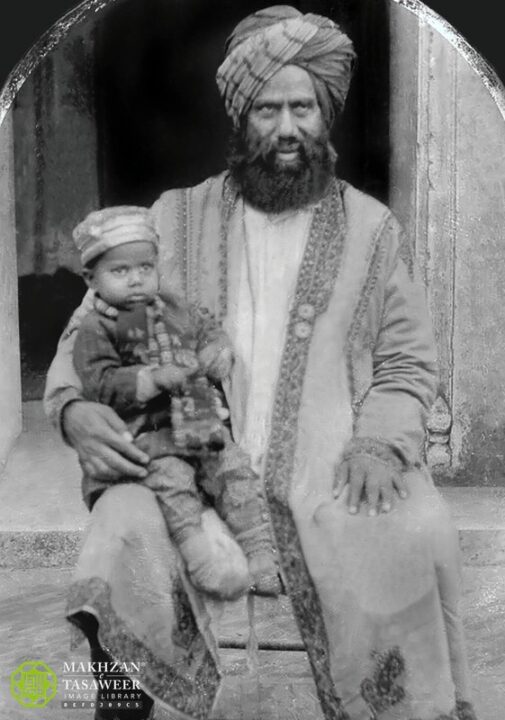

The list of Hakim Ali Hussain Khan’s pupils is as long as it is prestigious, worthy of notice being many who served the rulers of various princely states as court physicians: physician of Nizam Deccan, Hakim Muhammad Said; physician of the Rais of Tonk, Hakim Syed Altaf Hussain; and the royal physician of the Maharaja Kashmir, Hazrat Hakim Nuruddinra. (Ibid, p. 256)

The long list of his pupils is dotted with many who produced and/or translated works of Eastern medicine that serve as textbooks to this day.

Interesting it is to note that Hazrat Nuruddinra, on his way to Lucknow, also stayed at the same house of Maulvi Abdur Rahman Khan in Kanpur, who happened to be a close friend of his brother Sultan Ahmad – once a leading name in the printing trade.

En route to Lucknow, and before staying a night in Kanpur, Hazrat Nuruddinra stopped over at Muradabad and caught up with the sleep and rest that he had deprived himself of in Rampur. This stay lasted around a month or a month-and-a-half, according to his autobiographical account in Hakim-e-Haziq. Adding up the above events and their timings, it appears that Hazrat Nuruddinra arrived in Lucknow at Hakim Ali Hussain’s house, around autumn or winter of 1866.

That he recovered from insomnia by this time can be gathered from the fact that when Hakim Ali Hussain enquired about the purpose of his visit, he only stated that he had come to learn tibb.

Taken on by Hakim Ali Hussain in pupillage, Hazrat Nuruddinra felt that he had enough time and much more urge to learn Islamic studies alongside it. For this, he was referred to Maulvi Fazlullah Farangi Mahali, who was another scholar of renown in the Muslim circles of India.

Maulvi Fazlullah was a scholar of Islamic as well as secular studies. He was employed by Canning College soon after its inception in 1864. Farangi Mahal had a reputation of tutoring pupils with no scholarly lineage – a then scarce trend in Muslim India. Peter Hardy, through a random sampling, found that of a hundred Islamic scholars that died in the nineteenth century, 50 percent had an alim (Islamic scholar) for a father; of the remaining, 14 percent had received their learning at Farangi Mahal. (Peter Hardy, The Ulama in British India, p. 832)

Avril Powell, an esteemed historian of South Asian Islam, notes that in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Shi‘ites and Sunnis were eager to be taught by Farangi Mahali scholars. (Avril Powell, Contact and Controversy Between Islam and Christianity in Northern India, 1833-1857, 1983)

That Hazrat Nuruddinra opted to study with a Farangi Mahali scholar goes to show, once again, that he had a strong disposition for secular knowledge as much as he had for Islamic religious studies. Maulvi Fazlullah was famously known for being a maquli (a religious scholar with both secular and religious aptitude) who taught at Canning College, Lucknow. Nawab Kalb-e-Ali Khan, the ruler of Rampur, is said to have offered him a job at the palace, which he refused and remained at Canning College, alongside disseminating religious knowledge to his pupils at Farangi Mahal privately. (M Inayatullah Ansari Farangi Mahali, Tazkira-i-Ulama-i-Farangi Mahal, Ishaatul Uloom Barqi Press, Farangi Mahal, Lucknow)

While singing praises of the great teachers that Hazrat Nuruddinra was a beneficiary of, we must also note that the pupil too was of no less intellectual prowess. He records in his autobiographical account that while learning from Hakim Ali Hussain and Maulvi Fazlullah Farangi Mahali, he felt that his learning curve was not as steeply ascending as he aspired.

After what appears to be a period of a few months, Hazrat Nuruddinra sought permission of Hakim Ali Hussain to return to Rampur for further learning. Hakim Ali Hussain informed him that he had been invited by Nawab Kalb-e-Ali Khan of Rampur to join his court as a royal physician; he invited Hazrat Nuruddinra to join him in the service of Rampur.

Already a fan of Rampur and willing to head there, Hazrat Nuruddinra took no time to consider and joined Hakim Ali Hussain on this venture. He stayed with Hakim Ali Hussain for two years in Rampur before asking for leave to pursue education in hadith. Hakim Ali Hussain advised him to seek this treasure in Delhi – an established centre of excellence for hadith. This appears to have been in 1869.

The first name that anyone would consider in terms of hadith in those days was that of Maulvi Syed Nazir Hussain of Delhi. The same, naturally, was Hazrat Nuruddin’s first choice when he arrived in Delhi. However, as Hazrat Nuruddinra narrates, Maulvi Nazir Hussain was detained on suspicion of sponsoring the Jihadist movement based at the North-Western frontier against the British – more commonly known as Tahrik-e-Mujahidin.

Before moving on, it is essential that a correction must be made. In the third volume of Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyyat, the author, Dost Muhammad Shahid Sahib, has estimated the year of Hazrat Nuruddin’s arrival at Delhi to be 1864/65. However, the timeline that we have closely drawn above, suggests that he arrived there in c. 1869. A closer look at the series of events around Maulvi Nazir Hussain would be appropriate at this point.

Maulvi Nazir Hussain was tried for involvement in the Ambala Conspiracy of 1863 on the basis of suspicious letters found in his possession; addressed to and from persons involved in the jihadist movement of the Mujahidin in the Frontier Region. He was arrested in 1864 and acquitted in 1865.

As more evidence came to the surface, the case was reopened in 1869 and Nazir Hussain’s house was once again searched. It is not surprising to note that most works in Urdu on this episode are heavily painted with bias and prejudice by his proponents and opponents alike. Most such works suggest that although his house was searched again, the police could not put together a sufficient amount of evidence to arrest him. Although this is not entirely false, it is not the fact of the matter either.

In the official records of the trial, a letter from “Special Deputy Inspector-General of Police to Inspector-General of Police, Lower Provinces, dated Calcutta, 26th February, 1869”, reads:

“[…] I beg to suggest that the Punjab Government may be moved to direct the detention of Moulvie Nazeer Hoosain as a prisoner, in accordance with the spirit of Regulation III of 1818.”

Another letter, “From the Magistrate, to the Deputy Commissioner of Delhi; dated Delhi, 19th March 1869” reads:

“[…] I have admitted Omaid Ali as Queen’s evidence in the case. It was on his information that Izdah Bux, Nazeer Hoossain, and Attaoollah were arrested […]”

The same letter refers to Nazir Hussain as “Prisoner No 4” and goes on to suggest that “the investigation which has begun at Delhi be carried on, as indicated in Omaid Ali’s confession, Rawul Pindee and Peshawar, and that Omaid Ali, alone be retained in custody […]”.

“The Diary of Moonshee Ishree Pershad, Deputy Magistrate”, dated 18 March 1869, reads:

“Mr Carr Stephen was engaged in drawing his report. From what I heard him reading the rough draft of the report, I understand that he does not propose the trial of any four men, viz., Karree Omaid Ali, Nazeer Hoossain, Izdah Bux, and Attaoolah, who are detained by the orders of the Punjab Government under Act V, of 1841.” (Selections from Bengal Government Records on Wahhabi Trials 1863-1870, Asiatic Society of Pakistan, Dacca, 1961)

Since Nazir Hussain was not imprisoned and tried, but only detained in the second episode of the Ambala Conspiracy Case in 1869, it is commonly misunderstood that he was never in custody on this occasion. From original records of the proceedings of the case, we have seen above that Maulvi Nazir Hussain was in custody during parts of February and March of 1869.

This quite clearly places the arrival of Hazrat Nurrudinra in Delhi in early 1869.

As the only motive for his travel to Delhi was unfulfilled, he decided to travel to Bhopal and excel in the field of his most desired discipline of tibb. His journey to Bhopal was an eventful one, where, in his short stays here and there, he was able to help people through his knowledge of tibb. From all accounts in this regard, the journey seems to span over a few months before he finally reaches Bhopal. We are inclined to assume that this must have been during the latter half of 1869.

It is important to understand what Bhopal actually stood for in those days. The ruler of the princely state of Bhopal at that time was Sikandar Jahan Begum. “She was renowned as a patron of cultural and religious pursuits throughout India and across the Muslim world.” Bhopal had earned the reputation of a “cultural centre on the model of the Mughal court in Delhi, patronizing various literary figures, including the famous Urdu poet, Ghalib”. During the reign of Sikandar Jahan Begum, “the mood within the Bhopal court was rather more sombre, as it was not poets but religious scholars that she invited to settle and find employment within the state.” (Claudia Preckel, The Roots of Anglo-Muslim Cooperation and Islamic Reformism in Bhopal, presented at Conference on Reciprocal Perceptions of Different Cultures in South Asia, Bonn, 15-18 December 1996)

Historians agree that Munshi “Jamaluddin Khan, who acted as Sikandar’s diwan (chief minister) from 1852 until her death” was the most seasoned scholar and influential figure in the court of Bhopal”. (Ibid)

Apart from Bhopal being an excellent centre of learning, another impetus of Hazrat Nuruddinra to move to Bhopal can be identified in the religious disposition of the state. Munshi Jamaluddin’s affiliation to the Ahl-e-Hadith had greatly influenced the Begum and, consequently, her court and courtiers as well as the general mood of the state.

Jamaluddin was known in the Muslim circles of India as a “distinguished theologian on account of having studied in Delhi with the descendants of Shah Waliullah (1703-63) and taken part in the religious reform movement of Sayyid Ahmad of Rai Bareilly (1786-1831), known as the Tariqah-i-Muhammadiyya, before arriving in Bhopal.” (Ibid)

However, at the same time, Jamaluddin was wise enough not to steer the political stance of Bhopal towards that of “Sayyid Ahmad Bareilly in […] launching jihad (sacred war) against the British in India”. (Aziz Ahmad, Studies in Islamic Culture in the Indian Environment, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 2000)

Always keen on bringing reputable scholars to the court of Bhopal, Jamaluddin was the one who had convinced Sikandar Jahan to provide state employment to Syed Siddiq Hasan, a leading figure in the Ahl-e-Hadith movement. It appears that Jamaluddin had supported Siddiq Hasan Khan owing to the latter’s father, Syed Awlad Hasan, being a disciple and follower of Syed Ahmad Barelvi and, later, of Shah Abdul Aziz. (Siobhan Lambert-Hurley, Muslim Women, Reform and Princely Patronage, Routledge, 2007)

That Jamaluddin was always in pursuit of scholars is evident from his first rendezvous with Hazrat Nuruddinra. He found Hazrat Nuruddinra in a mosque and decided to interview the stranger. A brief exchange of dialogue seems to have proved sufficient for Jamaluddin to gauge the intellectual depth of Hazrat Nuruddinra, not to mention his strong Ahl-e-Hadith disposition.

The next moment, Hazrat Nuruddinra was housed in state quarters by Jamaluddin and instructed to join him at every meal. (Mirqat al-Yaqin)

Jamaluddin had great love for not only learning but also for teaching the Holy Quran. For this, he would hold daily sessions (dars) for the general public and also in private for Sikandar Jahan Begum. Hazrat Nuruddinra made it a point to attend every general session and was asked by Jamaluddin to contribute to the exegesis and interpretation. This classed him among the great scholars of Bhopal to whom many would flock for Quranic knowledge.

Jamaluddin arranged for Hazrat Nuruddinra to excel in the knowledge of Quran and hadith and gave him in the pupillage of Maulana Abdul Qayyum (the son of Maulana Abdul Hai Budhanwi, a Khalifa of Syed Ahmad Barelvi).

Hazrat Nuruddinra took lessons in major works of hadith from Maulana Abdul Qayyum (of Bhudhana), who was then mufti of the state of Bhopal – an initiated disciple at the hand of Syed Ahmad Barelvi who taught Islam in light of Shah Waliullah’s ideology. (Abul Hasan Ali Nadawi, Karwan-e Iman-o-Azimat, Syed Ahmad Shahid Academy, Rai Bareilly, 1980)

He was classed among the top scholars and teachers of Islamic theology in India.

Having remained in Bhopal, in both teacher and taught roles, Hazrat Nuruddinra did not take it to be his final destination – although it would have been ideal if one were in pursuit of the worldly treasures of knowledge, fame, respect and wealth. As soon as he had earned enough money to become eligible for Hajj, he departed Bhopal and headed straight to Mecca.

Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyyat places his arrival in Mecca around 1865 or 1866. The gap of four to five years filled above, we can reasonably assume that Hazrat Nuruddin’s arrival in Mecca would have happened in 1869/70.

The Hijaz days

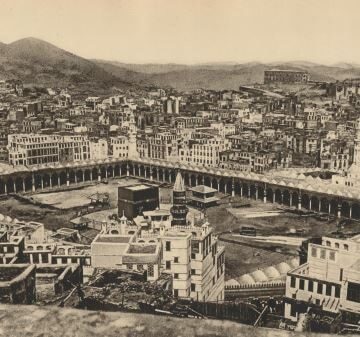

Having arrived in Mecca, Hazrat Nuruddinra immediately engaged himself in learning Islam from the eminent scholars that had gathered there from many parts of the Islamic world and had established their madrasas. Among his teachers were eminent scholars like Sheikh Muhammad Khizraji, Sheikh al-Hadith Syed Hussain and Maulvi Rahmatullah Kairanvi.

While hadith remained his area of specialisation, it appears that Rahmatullah Kairanvi’s knowledge of Christianity and his skills of polemics with Christians rubbed off on him. Rahmatullah Kairanvi was well known for his debate with Rev CG Pfander in 1854, known more commonly as “The Great Debate of Agra” owing to its venue.

The debate had been a great success and had helped restore Muslim zeal against the surge of Christian missionaries in India. (Muslim-Christian Confrontation: Dr Wazir Khan in Nineteenth-century Agra, in Religious Controversy in British India: Dialogues in South Asian Languages, Ed. Kenneth Jones, State University of New York Press, 1992)

Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas has also acknowledged and praised the efforts of Rahmatullah Kairanvi in this debate. (Arbain III, Ruhani Khazain, Vol. 17, Nazrat Nashr-o-Ishaat, Qadian, 2008)

Rahmatullah Kairanvi had another associate, namely Dr Wazir Khan, assisting him throughout the course of the debate. Both had fled India in the wake of the 1857 mutiny and migrated to Mecca – remaining there for the rest of their lives. (Muslim-Christian Confrontation: Dr Wazir Khan in Nineteenth-century Agra, in Religious Controversy in British India: Dialogues in South Asian Languages, Ed. Kenneth Jones, State University of New York Press, 1992)

While Hazrat Nuruddinra not only benefitted from the religious knowledge of Rahmatullah Kairanvi, he was also inspired by Dr Wazir Khan’s medical and surgical practices. He mentions how Dr Wazir Khan had treated the Sharif of Mecca’s bladder-stones by importing a surgical device from France. Hazrat Nuruddinra remembers the incident as a point where he seriously considered enhancing his knowledge of Western medicine; a skill that he would readily apply during his career in Eastern medicine. (Hakim-e-Haziq)

Hazrat Nuruddinra reminisced how he would always consult further reading material on whatever he learned, for, in his own words, “even then, I was of a liberal and independent nature, and one that sought logical reasoning.” (Mirqat al-Yaqin)

Having stayed in Mecca for about a year-and-a-half (Hakim-e-Haziq) Hazrat Nuruddinra moved to Medina and became a pupil of Shah Abdul Ghani Mujaddidi. Again a disciple of Shah Abdul Aziz’s (hence of Shah Walilullah’s), Shah Abdul Ghani was an unparalleled scholar of hadith who produced a whole array of great scholars. (Hakim Abdul Hayy, Nuzhatul Khawatir)

Hazrat Nuruddinra pledged allegiance at the hand of Shah Abdul Ghani and, as he states himself, “spent a long period of time” with him in Medina. (Mirqat al-Yaqin; Hakim-e-Haziq)

At the time of pledging allegiance, Shah Abdul Ghani had said to Hazrat Nuruddinra that he would have to stay with him for at least a year. (Mirqat al-Yaqin)

After his stay in Medina, Hazrat Nuruddinra returned to Mecca for another Hajj. Although none of his biographical accounts mentions his first Hajj, there are reasons to assume that he did perform a Hajj during his first stay at Mecca.

Mirqat al-Yaqin has it that:

“When I was about to leave for Medina, I left my belongings and a lot of money with him [an acquaintance mentioned earlier] and told him, since I would be in Medina for quite a long time, to invest the amount in a business and benefit from the profit that he would earn. I would then take it back when I came for the next Hajj; ‘Have it ready before the Hajj days.’ Upon return and having performed Hajj, I asked for the money […]”.

This incident not only shows that Hazrat Nuruddinra had performed Hajj twice but also that he returned from Medina in a year’s time – the period between one Hajj and another. This is also confirmed by Shah Abdul Ghani’s assertion that Hazrat Nuruddinra would have to remain with him for a year.

Since a hard-and-fast timeline cannot be ascertained from Hazrat Nuruddin’s own accounts, or even those written afterwards in Hayat-e-Nur and Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyyat, we are left with fragmented pieces of information to be put together for an approximate one.

Mentioning his first stay in Mecca, Hazrat Nuruddinra says that “it was around 1285 or 1286 Hijri […]”. This equates to 1868/69, hence ironing out the rest of the timeline that follows. (Hayat-e-Nur, p. 130; Mirqat al-Yaqin)

If his first arrival in Mecca is to be assumed in 1868/69, his stay there for a year-and-a-half takes us to around 1871. A year-long stay at Medina takes us to 1872. Hajj that year happened at the end of September. Taking him to have departed sometime in October, it is safe to assume his return to India by the end of the same or early part of the New Year.

The weekly Badr, Qadian, of 27 July 1905, published the news of the death of his wife who, as the obituary states, “got married to [him] upon his return to Bhera from his educational tours of India and Arabia, when he was around 30 years of age”.

Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyyat sees his age to be around 30 when he arrived back from Hijaz on similar grounds. Therefore, our timeline is now aligned here with that suggested in Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyyat. It will, however, still swerve a bit in some coming parts of this article.

That he was “around 30” when he returned can also be testified from one of his own accounts about the days he spent in Mecca:

“Since I was in my youth and around 24 or 25 years old, and owing to my physical strength, I would only eat a date with water or milk”. (Hayat-e-Nur, p. 60)

Back home – Bhera

Hazrat Nuruddinra returned to his hometown with the reputation of a scholar who had travelled far and wide – Hijaz being the jewel in his crown– and had now returned home. He was received with great honour and respect by the locals as a son of Bhera who had once left the town and was now returning as a scholar.

However, this title of a “scholar” came at a heavy cost as it also carried with it a prefix of “Wahhabi”. Anti-Wahhabi sentiment was not only rife in Muslim circles, but in the circles of the British-Indian government as well. (The jihadist bent of the Ahl-e-Hadith has been touched upon above in relation to the Mujahidin Movement and its Wahhabi sponsors.)

This left Wahhabis in an extremely vulnerable state, so much so that Hazrat Nuruddinra had to face bitter opposition in his own hometown. Amongst decrees that declared him (along with other Wahhabis) a heretic, and attempts on his life, Hazrat Nuruddinra was to spend around four years in his hometown – until the end of 1876.

Upon arrival, he got married for the first time and settled down as a teacher of Islamic studies, while also running a mat‘ab (clinic) as a part-time occupation.

He had established his practice in the terrace of his family home, but with all the decrees and persecution that surrounded his person, it seems that the practice struggled; making ends just about meet. (Mirqat al-Yaqin)

He states in his personal account that he was penniless in those days.

After some time, which again is not specified, his father passed away and his brother, Maulvi Sultan Ahmad, asked him to testify in writing about an issue related to inheritance.

Hazrat Nuruddinra took this as a signal and decided to move out of the family home to a room in a nearby mosque along with his practice.

With no resources but a huge deal of hope, he started building his own house. He borrowed 1,200 rupees from a Hindu for this venture, not knowing how the loan would be returned. The building, even before it had started, went through a turbulent phase where land ownership, planning permission and the paraphernalia of real estate kept popping up from time to time.

In search of employment

Now that he owed 1,200 rupees to the Hindu lender, he had no clue as to how it would be paid back. This, given the information from his biographical accounts, must have been December 1876.

His once benefactor, Munshi Jamaluddin of Bhopal had invited him to take up employment in the court of Bhopal. He wanted to avail the opportunity as this seemed to be the only way to pay off his loan.

As he decided to head to Bhopal, he came across a long-time friend, Malik Fateh Khan, who visited him in Bhera and informed him that all rulers of princely states and their courtiers had assembled at Delhi where Lord Lytton, then viceroy of India, was holding the Delhi Durbar.

This Delhi Durbar was held on 1 January 1877 to celebrate the proclamation of Queen Victoria as Empress of India. For this purpose, Lord Lytton had invited all rulers of princely states to grant them titles and medals as an acknowledgement of their solidarity with the British Crown. Munshi Jamaluddin was accompanying the Begum of Bhopal as her diwan (chief minister). All dignitaries were staying in tents in a vast tent-city erected specially for their accommodation.

Hazrat Nuruddinra travelled from Bhera to Lahore and then from Lahore to Delhi by train. This was in the last days of December 1876 as the Durbar was to assemble on New Year’s Day.

It was in these days, leading up to the Durbar, that Munshi Jamaluddin’s grandson fell ill. With Hazrat Nuruddinra around, Munshi Jamaluddin turned to him and remunerated him 700 rupees as a reward for the timely treatment and another 500 rupees later. Thus, the loan of 1,200 rupees was ready to be paid back.

Jamaluddin insisted to take Hazrat Nuruddinra along to Bhopal, to which Hazrat Nuruddinra wholeheartedly agreed. This marked the start of a second Bhopal episode in Hazrat Nuruddin’s life.

His own accounts suggest that he was employed in Bhopal at a monthly salary of 200 rupees and was allowed private practice in his own time. However, this only lasted a few months.

It was upon his return to Bhera from Bhopal that he finally headed to Jammu to work as the physician for the Maharaja of Kashmir. Before proceeding to the Kashmir episode of his life, we must pause and untangle a few facts.