Asif M Basit

Introduction to the Maharaja of Kashmir

It seems best to first look at the autobiographical accounts of Hazrat Nuruddinra before delving into the timeframe of his move to Jammu and Kashmir.

In Hakim-e-Haziq, Hazrat Nuruddinra, mentioning how successful his practice in Bhera had become, says:

“A person from Jammu, suffering from Tuberculosis, came to see me in Bhera and stayed in my neighbourhood. His name was Lala Mithra Das. When I had treated him and he had recovered, the prime minister of Jammu, Diwan Kirpa Ram happened to visit Pind Dadan Khan. He, along with Bakhshi Jawala Singh (an uncle of the patient) mentioned me to the Maharaja.”

After this, he carries on mentioning some other success stories of his practice in Bhera and then states:

“I now close the Bhera part here […] and move on to Jammu”.

Tarikh-e-Ahmadiyyat rightly identifies the time of Mithra Das’s treatment and the mention of Hazrat Nuruddinra to the Maharaja in 1876, but that he moved to Jammu to work as the Maharaja’s physician at that very time seems unlikely.

Since Diwan Kirpa Ram deceased on 22 September 1876 (Times of India, 30 Sept 1876), it is probable that he mentioned Hazrat Nuruddinra to the Maharaja sometime during the same year.

But the fact that Hazrat Nuruddinra is still seen in need of employment at the end of 1876 and plans to visit the Delhi Durbar in January 1877 and then travels to Bhopal to be employed by the state indicates that Hazrat Nuruddinra was not in Kashmir before mid-1877.

From the above, we find it clear enough to believe that Kirpa Ram’s journey through Pind Dadan Khan and introducing Hazrat Nuruddinra to the Maharaja must have happened before September 1876 (the time of Kirpa Ram’s death) but the Delhi Durbar and the Bhopal episodes of early 1877 do not allow placing Hazrat Nuruddin’s move to Jammu in 1876.

Therefore, we can confidently say that Hazrat Nuruddinra joined the court of the Maharaja as a physician in mid or late 1877.

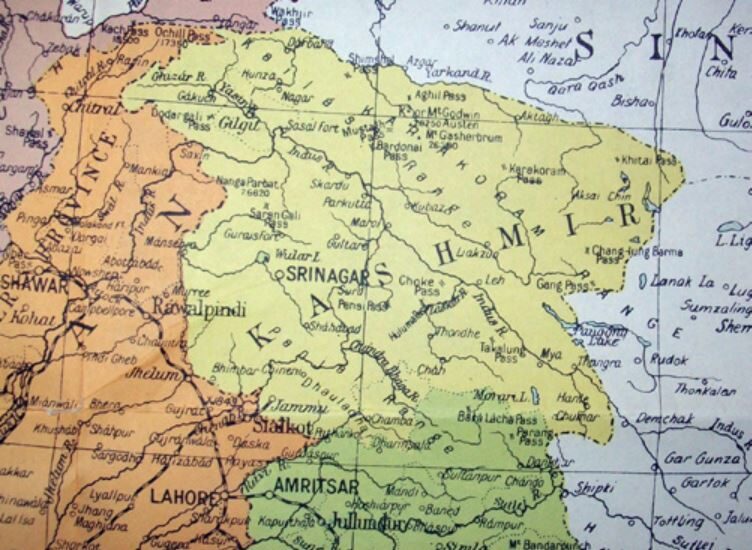

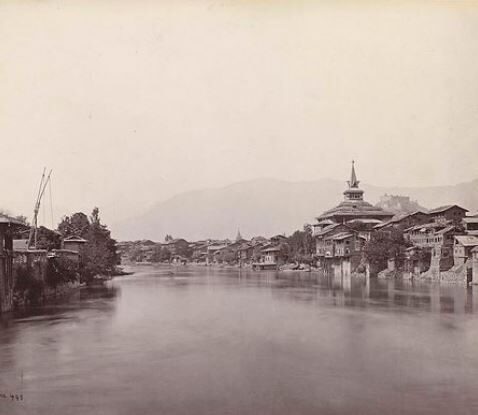

Kashmir in the times of Ranbir Singh

In his biographical accounts, Hazrat Nuruddinra is sometimes found mentioning the Maharaja as a very wise person, and, at others, as a man of very low intellectual calibre. This is because he remained in service of two Maharajas, one after the other. He joined the court during the time of Ranbir Singh and, after his death in 1885, continued serving his son Pratap Singh, who ascended as the Maharaja.

Maharaja Ranbir Singh had inherited the throne of Kashmir from his father, Maharaja Gulab Singh, the founder of the State of Jammu and Kashmir. What he had also inherited from his father were British intrigues in the affairs of Kashmir, which both the father and the son had successfully kept at bay.

The British, having sold Kashmir to Gulab Singh, had immediately started to regret the decision as this move meant being disconnected from the Russian borders and, hence, becoming unaware of Russian intrigues – an obsession that gave sleepless nights to the British government.

Immediately after the sale and the lodging of Gulab Singh as the sovereign of Kashmir, the British had tried to have some sort of presence in the Maharaja’s court. Gulab Singh, shrewd as he was, had managed to not let this happen, and so did his successor-son, Ranbir Singh. Records show that the British Government had tried tooth and nail to install a Political Resident in Kashmir during the time of Ranbir Singh but the latter’s resistance led them to drop the idea. (Madhavi Yasin, British Paramountcy in Kashmir 1876-1894, Atlantic Publishers, New Delhi, 1984)

Since the British government remained the “Paramount Power” for Kashmir (Treaty of Amritsar, 1846) their intrigues took the better part of Ranbir Singh and they had finally managed to install an “officer on special duty” in Kashmir. This was seen as a win-win situation for both: The Maharaja thought he had avoided a British Resident; the British had got their foot in the door. (Madhavi Yasin, British Paramountcy in Kashmir 1876-1894, Atlantic Publishers, New Delhi, 1984)

This move, and the subsequent intervention of the British in state matters, led to a situation where Ranbir Singh realised that the British would not leave Kashmir in peace. He knew that the British will regain suzerainty by hook or by crook.

Edward E Meakin, a journalist who had had interviews with Ranbir Singh, once told a meeting of the East India Association in August 1889:

“I will relate an incident which occurred in the year 1876. I was one day sitting by the side of the late Maharaja of Kashmir talking over various matters […] The Maharaja suddenly turned to me and said: ‘I learned a great many things by my recent visit to Calcutta […] It was an open secret that the British Government wanted to annex Kashmir, and that it was only a question of time and skilful manoeuvring”.

Ranbir Singh further opened his heart by telling the journalist:

“I am a buffer; on one side of me there is the big train of the British possessions, and whenever they push northward, they will tilt up against me; then on the other side is the shaky concern Afghanistan, and the other side of it is the ponderous train and engine called Roos [Russia]. Every now and then, there is a tilting of Roos towards Afghanistan, and simultaneously there is a tilting upwards of the great engine in Calcutta; and I am the poor little button between them.

“Someday, perhaps not far distant, there will be a tilting from the North, and Afghanistan will smash up. Then there will be a tremendous tilt from the South, and I shall be buried in the wreck and lost!” (William Digby, Condemned, Unheard, Indian Political Agency, London, 1890)

These prophetic words by Maharaja Ranbir Singh were uttered in 1876 – the time that Hazrat Nuruddinra was about to join his service. Maharaja Ranbir Singh’s analogy and his references to the three players therein – Britain, Afghanistan and Russia – ought to be kept in mind as they set the stage for Hazrat Nuruddin’s time in Kashmir – his time of prosperity; of test and turbulence; of eventually parting with an unstable worldly kingdom to a mighty and heavenly one.

The court of Ranbir Singh

Ranbir Singh was given the gaddi (throne) of Kashmir by his father, Maharaja Gulab Singh to be trained for his future duties. During this period of regency, Ranbir Singh let the state machinery run on the settings of his father and made no major changes. However, when he was officially installed as Maharaja is when he made major changes in the revenue, civil and administrative spheres of the state machinery. Affairs of the judiciary were also seriously revised. (K L Kalla, The Literary Heritage of Kashmir, p. 76)

What makes the reign of Ranbir Singh distinct from those of other Dogra rulers is his contribution towards education. Although without any formal education himself, Ranbir Singh strove to establish a culture of education and literary learning in the State of Kashmir.

He established Pathshalas where “poetry, poetics, grammar, philosophy, mathematics, algebra and Euclid” (Dr Buhler’s report on Sanskrit Manuscripts) were taught, alongside “Vedas and nyaya”. (Pandit Gwasha Lal Kaul, Kashmir Through the Ages, Chronicle Publishing House, Srinigar, 1963)

KL Kalla, in The Literary Heritage of Kashmir, states:

“Whatever his own standard of formal education, it is a fact that Maharaja Ranbir Singh did his utmost to spread modern education in the State. His interest in the promotion of knowledge was not confined to the State. He donated one lakh of rupees when the Punjab University was being established and in recognition of his services, was elected the First Fellow of the University”. (Ibid, p. 77)

Dr Ghulam Mohyuddin Sufi, a renowned historian of Kashmir, asserts:

“Ranbir held gatherings on the model of Akbar when men of learning were gathered together for discussion of religious and social matters. Diwan Kirpa Ram was his Abu’l Fazl […]”. (Sufi, GMD, Kashir: Being a history of Kashmir, From the earliest to our own, University of the Punjab, Vol. 2, p. 802, Lahore, 1948)

We remind our readers that it was the same Diwan Kirpa Ram whose eye had seen the spark in Hazrat Nuruddinra and recommended him to Maharaja Ranbir Singh.

Sufi goes on to describe the grandeur of the learned court of Ranbir Singh:

“The names of important litterateurs were: Pandit Ganesh Kaul Shastri, Babu Nilambar Mukerji, Dr Bakhshi Ram, Dr Surajbal, Pandit Sahib Ram, Pandit Himmat Ram Razdan, Mirza Abar Beg, Hakim Waliullah Shah Lahauri, Sayyid Ghulam Jilani, Maulavi Nasiru-ud-Din, Maulavi Ghulam Husain Tabib of Luckhnow, Maulavi Qalandar Ali Panipati, Maulavi Abdullah Mujtahid-ul-Asr, Hafiz Hajji Hakim Nur-ud-Din Qadiani, Babu Nasrullah Isai.” (Ibid)

Sufi sees them as “the ornaments of the literary darbar of Maharaja Ranbir Singh.” (Ibid)

As mentioned above, Diwan Kirpa Ram was instrumental in gathering the intelligentsia in Kashmir. He is said to be dignified, of literary taste and was himself a seasoned author – Gulzar-e-Kashmir and Gulab-nama being his major works. (Ibid)

Richard Temple, who met Kirpa Ram in 1871 describes him as “a man of considerable intelligence, and ambitious of earning a good administrative repute for his master’s government”. (Richard Temple, Journals kept in Hyderabad, Kashmir, Sikkim and Nepal, Vol. 2, p. 144)

One of the greatest accomplishments of Ranbir Singh was the Dar al-Tarjuma (translation bureau) which he had established for translating world-class masterpieces into Dogri, Persian and other languages that the Kashmiri public could benefit from. (KL Kalla, The Literary Heritage of Kashmir)

This called for scholars from all parts of India to be employed by the Maharaja. Sukhdev Charak mentions this great literary and intellectual venture in the following words:

“This increased, in addition to the educational, the literary activity to such an immensity as has never been attained by the people of the State afterwards. For this purpose, he patronised scholars of all communities. This group of scholars included, besides numerous eminent teachers and experts, Fateh Singh, Hakim Fida Muhammad Khan, Maulvi Nur-ud-Din, Pandit Ganesh and Jeotshi Bashesharjoo.” (Sukhdev Singh Charak, Life and Times of Maharaja Ranbir Singh, Jay Kay Book House, Jammu)

The Maharaja had made certain reading material compulsory for all state employees to study and pass an examination to enter and maintain the service of the state. The examining and certificate awarding body comprised “scholars like Fateh Singh, Hakim Fida Mohammad Khan, Maulvi Nur-ud-Din, Pandit Ganesh and Jyotshi Bisheshwar”. (Ibid)

Out of all the learned men, Sufi particularly mentions one who excelled to world fame:

“Hakim Nur-ud-Din, his trusted physician, later became the successor of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian, the founder of the Ahmadiyya sect in the Punjab.” (Sufi, GMD, Kashir: Being a history of Kashmir, From the earliest to our own, University of the Punjab, Vol. 2, p. 802, Lahore, 1948)

It was this golden era – and the most peaceful one – of Dogra Raj where this “trusted physician” enjoyed years of medical practice as well as teaching and learning about Islam. The names in the long list of learned men are self-evident of the cultural and religious diversity that Ranbir Singh has established in the state where Hazrat Nuruddinra had chosen to live.

The death of Ranbir Singh

As Ranbir Singh grew old and his health started to deteriorate, the British government set their intrigues at an all-time high. Correspondence that took place between the Oliver St John, the officer on special duty, and Henry Mortimer Durand, the secretary of state for India, lay bare the net knitted by the British government and how it was spread across the machinery of the State of Kashmir.

Durand gave instructions to St John in the following words:

“(1) That if at any time the Maharaja’s death should appear to be near at hand the officer on Special Duty should arrange to be near at hand.

(2) That he should join the Maharaja at Jammu or wherever he may then be and prevent any disorder occurring […]”. (India Office Records, R/2/1073/194, Foreign Office, Government of India, secret letter to Oliver St John, dated 7 April 1884)

Oliver St John had, a year before Ranbir Singh’s death, informed the British government that Partap Singh, the heir-apparent, was not fit to succeed as Maharaja. He informed the British-Indian Government that:

“There is no doubt that the Maharaja has occasionally had serious thoughts of setting aside his two eldest sons, Partab Singh and Ram Singh, in favour of his third son, Amar Singh. Mian Partab Singh, the eldest, is about 30 years of age, and has besotted an intellect, never very strong, by habitual indulgence in the most degrading vices […] It is certain that he would be a very weak, if not a very bad ruler.”

He goes on to speak about Ram Singh, the second eldest son and second in line to the throne, also being an unsuitable successor. Then he mentions the third son, Raja Amar Singh:

“Amar Singh, is a very good-looking lad of 18, is a general favourite, and is at least superior in ability to his elder brothers. The Maharajah had at one time made up his mind to speak or write to His Excellency the Viceroy on the subject of nominating Amar Singh his heir, but was at the last moment induced to abandon the idea by fear of a public enquiry into his reasons for disinheriting his elder sons.” (Ibid, Memorandum dated 20 January 1884, by Sir Oliver St Joh, Officer on Special Duty in Kashmir)

The government, keeping in view Oliver St John’s report, wrote to the Secretary of State for India and suggested that although “the heir-apparent to the chiefship is said to be unfitted in character and habits to govern the State”, but it was in the greater interest that:

“[…] no encouragement should be given to the idea that an eldest son can be set aside at the will of his father”. (India Office Records, R/2/1073/194, Foreign Office, Government of India, secret letter to Oliver St John, dated 7 April, 1884)

The Secretary of State, upon receiving the above proposal, endorsed it and replied:

“While I regret to receive so unfavourable an account of the character of the Maharaja’s heir, I agree with Your Excellency’s Government [of India] in regarding as inexpedient any deviation, in the case of Kashmir, from the regular succession by order of primogeniture”. (Ibid, Secret Despatch from Secretary of State for India, No. 11, 23 may 1884)

He further emphasised in the same letter that “Mian Pertab Singh should be proclaimed immediately on his father’s death”. (Ibid)

Gulab Singh had kept the British intrigues in the State of Kashmir at bay and so did his son Ranbir Singh. The British government’s eager and desperate desire for Ranbir Singh’s death is evident from the letters above (and many more that have not been quoted for fear of deviating from the actual subject). Another shrewd ruler like Amar Singh could further delay their ardent desire to annex Kashmir. Hence, what most suited their agenda was an incompetent ruler like Partap Singh, who, to their good fortune, was devoid of any political sensibility or vision and of any abilities of a good ruler.

The British had envisaged the death of Ranbir Singh and the succession of Partap Singh as the best opportunity to install a British Resident Officer in the State of Kashmir. This had been communicated by the Government of India’s Foreign Department through a secret letter dated 1 August 1884 to Oliver St John. He was, when the long-anticipated time struck instructed to:

“[…] inform His Highness [the new Maharaja] and the members of his Darbar of the views and intentions of the British Government in regard to the future administration of the State. You should give them clearly to understand that His Excellency the Viceroy regards the existing condition of affairs in Kashmir as most unsatisfactory, and you should warn His Highness and those about him that substantial reforms must be introduced without delay. You should then announce that, with the view of aiding His Highness in the introduction and maintenance of those reforms, the Viceroy has decided to give His Highness the assistance of a resident English Officer, and that for future the British representative in Kashmir will have the same status and duties as the Political Resident in other Indian States in subordinate alliance with the British Government.” (Ibid)

So desperate was the move that upon the death of Ranbir Singh on 12 September 1885, Oliver St John headed straight to the new Maharaja to inform him of the Government’s instructions. The Darbar staff made it clear to St John that due to the mourning rituals, the Maharaja would not see anyone, but he pushed his way and met the Maharaja, bringing to his knowledge all that had been decided about his fate. (Ibid, Oliver St John to Durand, 18 September 1885)

The ascension of Partap Singh

Hayat-e-Nur suggests that Hazrat Nuruddinra had cordial relations with Raja Amar Singh and those who were envious of it conspired to have Hazrat Nuruddinra expelled from the court and also from Kashmir. However, research carried out for this article was able to tap on official documentation which presents a completely different story. The following detail, lengthy and windy it may seem, suggests that the situation was completely different, although Hazrat Nuruddinra spoke fondly of Raja Amar Singh on a number of occasions in his autobiographical accounts.

Partap Singh’s ascension to the gaddi as Maharaja and Oliver St John’s promotion from Officer on Special Duty to Political Resident in Kashmir happened simultaneously; with this started a tug of war that left the administration of Jammu and Kashmir torn to pieces, never to be put together again.

As we have seen above, the resident’s only ambition – fuelled by the British Indian government – was to control all affairs of the State of Kashmir. Installing a Political Resident was the government’s first move; how he was to manoeuvre the state of affairs in the desired direction was now to be decided.

We know from the facts presented above that Oliver St John had already informed the government about Partap Singh being unfit for the role of the Maharaja. Also, that his younger brother Amar Singh was seen as a much more suitable person for administrative matters. The policy of “divide and rule” had worked for the British so very well that not a minute was lost in employing the same; it was decided that the palace had to be split to gain full control of the conflicting forces.

Oliver St John, on 8 January 1886, wrote to the government:

“In a memorandum written two years ago on Kashmir affairs, I remarked that Mian Pertab Singh, then the heir-apparent, would, if he ever succeeded to the Chiefship, prove a very weak, if not a very bad, ruler. He has now been nearly four months in power, and has shown himself equally weak and bad […]

“His Highness’s two brothers, Mian Ram Singh and Mian Amar Singh, were at once and ostentatiously excluded from all participation in affairs. There then remained only Diwan Anant Ram, the titular Prime Minister, Gobind Sahai, his cousin, formerly Vakil in attendance on His Excellency the Viceroy, and Babu Nilambar Mukerji.” (Ibid)

The two brothers, Ram Singh and Amar Singh had gathered that the only way to gain power was through the resident; the resident had gathered that to stay on top of everything was by having the brothers on his side. The resident continues in the same letter:

“On the 26th of December the two asked me to come and see them, and begged me to interfere to save both themselves and the State from ruin […]

“Mian Amar Singh then showed me, and afterwards gave me, copies of photographs of documents which, if genuine, as I have reason to believe them to be, place the criminal foolishness of the Maharaja and his unfitness to rule beyond doubt”. (Ibid, Folio 40-41)

Purging Partap Singh’s court

The above correspondence clearly shows that Partap Singh could not be deposed owing to cultural traditions and fear of a public uprising, but he had to be set aside. To set him aside, everyone close to him had to be purged from the court. And this, consequently, meant that the administrative décor set up by Ranbir Singh – and inherited by Partap Singh – had to be purged from the darbar; lest any element of resistance to the British agenda remained behind.

So the newly appointed resident, Oliver St John, and his successors took it upon themselves to not only portray Partap Singh as corrupt, foolish, insane, superstitious and anything that could prove him unworthy and unfit for his inherited office. The same had to be done to everyone around him in his court. The groundwork had started already through Oliver St John’s letter, quoted above and dated 8 January 1886. He further wrote:

“As long as Maharaja Pertab Singh is allowed any power, that power will be misused. Every encroachment on the independence, as compared to other feudatories, which the late Maharaja was allowed to retain, will be fought with every possible weapon; no real reform will be made, and such measures as may be forced upon the Darbar will be grudgingly carried out and evaded in every possible way, while the resources of the State will be squandered on unworthy favourites.” (Ibid)

As Oliver St John was delegated other duties, he was succeeded by TJC Plowden as Resident in Kashmir. The narrative had to remain the same and so it did. Plowden compiled a detailed report titled “Report on the affairs of the State of Jummoo and Kashmir”, marked it as “Confidential” and sent it off to the secretary to the government of India, foreign department. This report, dated 5 March 1888 and spanning 18 pages, was a reinforcement of the idea that the Maharaja was unfit for the office, was under the influence of superstitious soothsayers and had “favourites” around him. The whole report can be summarised in one sentence: The Maharaja must be kept away from state affairs and all “favourites” must be disgraced and kicked out of the darbar. (Details: Report on the affairs of the State of Jummoo and Kashmir by Plowden, IOR/1073/194)

Feeling that the report might not have been enough, he wrote to the Foreign Department again on 28 March, 1888. He wrote:

“In continuation of this office No.12-C, dated 8th March, I have the honour to enclose copy of the paper complaining of the Maharaja referred to in paragraph 22 of my report on the affairs of Jammu and Kashmir”. (Ibid, Folio 48)

This letter summarised and further emphasised the charge laid against the Maharaja “that he surrounded himself with disreputable and fraudulent persons whose tool he became and also at whose instigation he entered in a course of reckless extravagance.”

With his letter, he attached a lengthy document titled “Translation of petition of certain Princes and Sirdars of the Jammu State to the address of the Resident in Kashmir”.

The petition elaborated how disgraceful and unworthy a man Partap Singh was and had always been. But since the “favourites” had to be completely purged from the state, the first point of the petition read:

“The present Maharaja when he was heir apparent, attempted to take the life of his father and brothers, that he might more quickly ascend to the Gaddi and ruin the State and empty the Treasury. Moreover to carry out his designs he surrounded himself with low-born persons such as Mohd. Bux Najumi (astrologer), Shisti Chander (Bengali), Mian Chatru, Bakhshi Ram Lubaid, Nehalu Teka, Lal Man, Karam Singh, Sheikh Miran Bux, Sawal Singh, Prem Nath, Amir Jiwar, Set Ramanand, Sheikh Fateh Mohammad, Moulvi Nur Din, Pandit Pitamber etc. persons who stayed with him and took lacs of rupees and valuable jewels and clothing from him.” (Ibid, Folio 54)

This petition was signed by none else but the brothers of the Maharaja, namely Raja Amar Singh and Raja Ram Singh, along with Diwan Lachman Das, Wazir Shibcharan and Mian Lal Din.

Before we come back to Hazrat Nuruddin’s story, it must be noted here that of those declaring Hazrat Nuruddinra a “low-born” and as one who had caused much harm to the state treasury through their closeness with Partap Singh, is Raja Amar Singh.

Now that the stage was set to have the Maharaja side-lined as defunct, the Indian Government was still grappling with the native culture where doing so could create public unrest and uprising. So Plowden’s conspiracies, fully backed by the brothers of the Maharaja were at an all-time high, when Plowden was transferred and replaced by Parry Nisbet as the new Resident in Kashmir.

Nisbet had been a close friend of Maharaja Ranbir Singh, and later of Partap Singh as well. This once-upon-a-time friendship left the Maharaja relieved of many worries, later to realise that political ambitions always supersede friendship and cordial relations. Nisbet was there to carry on in executing the agenda that had been unfolding during the times of his predecessors, Oliver St John and Plowden.

The Russian Gambit

Raja Amar Singh and his associates took leverage of the change and assisted Nisbet in his conspiracies against the Maharaja and his “favourites”.

On 25 February 1889, Raja Amar Singh handed Nisbet a bundle of letters written by the Maharaja to the Tsar of Russia. The letters were written in Dogri and appeared to be in the Maharaja’s own handwriting.

Without any investigation, Nisbet reported this discovery to the Indian Government and pushed that the Maharaja be deposed with immediate effect. However, Nisbet’s enthusiasm was not shared at the same level by the Viceroy or Henry Mortimer Durand, the foreign secretary. Durand, who was well aware of Raja Amar Singh’s ventures against the Maharaja, wrote back that using these letters as leverage for deposing the Maharaja and his associates would make the government “wash a great deal of dirty linen in public”. (National Archives of India, Lansdowne Papers, 7B(i), pp. 535-537)

However, Nisbet approached the Maharaja and told him what grave consequences the letters could have on the repute of the Maharaja and his family, and how the public would lose confidence in him and the ruling family. The Maharaja, although denying writing any such letters, appeared tired and worn of the conspiracies. He consented that he was ready to accept any proposal of the Indian government as long as his face and that of his family could be saved from shame before the public. This was on the 7 and 8 March 1889. (India Office Records, R/2/1073/194, Foreign Office, Government of India, Nisbet to Foreign Office, Government of India, Folio 173)

On 8 March 1889, Raja Amar Singh brought to the Resident an edict written by the Maharaja where he gave consent to stay away from all administrative affairs of the state and let the government decide how the affairs were to be managed. (Ibid, Nisbet’s report on Kashmir Affairs, 20 March 1889)

On 26 March 1889, Foreign Secretary for the Government of India, Mortimer Durand, wrote to the Resident in Kashmir (Parry Nisbet) that a State Council be formed and made responsible for running the affairs of the State. The Maharaja was to be kept aloof and confined to his palace. As to the functionality of the State Council, Durand wrote:

“Raja Amar Singh will be president. The Council will have full powers subject to provision that they must consult you before taking any important step and that they must follow your advice whenever you may offer it.” (India Office Records, R/2/1073/194, Folio 178)

The prophetic apprehensions of Ranbir Singh were thus manifested. The mighty engine of Britain, obsessively paranoid of Russian intrigues, had pushed upwards with full force and the State of Kashmir, like a ripe fruit, had fallen straight into the hands of the British Indian government; or out of the pan, into the fire, to put it more factually.

A new Kashmir for Hazrat Nuruddinra

Gone were the days of Maharaja Ranbir Singh and his court that thrived on knowledgeable and intellectual scholars. Kashmir was ablaze with political conspiracies and more like its famous autumnal Chinars. What now prevailed in the court of the Maharaja was an atmosphere of dysfunctionality and lowly tactics for survival.

We can imagine what grief this must have caused for a man with love for knowledge. With a magnificent background of learning and scholarship, Hazrat Nuruddinra had certainly not signed up for such hostile atmosphere.

Although his own accounts do not speak much about the anguish he suffered in this new setting, the correspondence that took place between him and his spiritual master, Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas of Qadian, tells a very sorrowful story.

Hazrat Nuruddinra seems to have found this spiritual master in 1885 (Maktubat-e-Ahmad, being letters of Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Vol. 2). This was around the time when Ranbir Singh was succeeded by Partap Singh and Kashmir had turned into nothing more than a political theatre. The great vacuum left behind by the fall of a centre of learning and knowledge got filled by his acquaintance with the man who had only just started calling the world to the Kingdom of God.

It is very unfortunate that we do not have the letters written by Hazrat Nuruddinra, but the replies by Hazrat Ahmadas were kept safe and published as Maktubat-e-Ahmad. These replies speak sufficiently for their missing counterparts.

It appears that the “favourites”, once employed by the Maharaja’s court, were made to revise their contracts. These contracts were to be signed on terms and conditions set by the council. This is evident from Durand’s letter (dated 26 March, 1889 and quoted above) where he instructs the Resident as such:

“You should also ascertain requirements of the State in regard to trained subordinate officials and suggest precise conditions to which Maharaja will be expected to conform. He must have adequate but no extravagant allowance and must resign all power of alienating State revenue.” (India Office Records, R/2/1073/194)

It appears that Hazrat Nuruddinra resigned from the State service in the early summer of 1886. Hazrat Ahmadas wrote to him on 20 June 1886:

“Your resignation from the job is apparently disheartening; but you must have seen some wisdom behind it”.

Another letter from Hazrat Ahmadas, dated 7 July 1886, addressed to Hazrat Nuruddinra reads:

“That your resignation has not been accepted is just as I had desired. God willing, promotion will follow soon.”

But our great intellectual seems dissatisfied. This is gathered from another letter by Hazrat Ahmadas in 1886 (date not given):

“In my opinion, you should not quit the job. Even if they offer you a lower pay, you should accept it. Deal with everyone with good morals and dignity. A believer is expected not to make hasty decisions and that too without consultation. I, therefore, advise you not to dissociate yourself [from the employment]. I am disturbed to know that you resigned when you had told me earlier that this dissociation is not from your side. However, you should now aim at trying to stay in this job.”

Letters from early 1887 reflect the great distress and anguish that struck Hazrat Nuruddinra in the unfavourable atmosphere he was living in. For instance, a letter from January 1887 reads:

“If your state of sloth and anxiety is a physical ailment, then you would know its cure and treatment better than me. If it is out of spiritual reasons, then there is no better cure than what Allah the Almighty has given us […]

“So it is best to take God the Almighty to be our Provider and Carer; and to remain steadfast through tests and tribulations is the only cure to sloth and anxiety.”

On 13 February 1887, Hazrat Ahmadas wrote to him:

“May Allah the Almighty, through His powers and His benevolence that have left in awe the whole world, rescue you from your sloth and fear and anxiety.

“It has been a very appropriate decision to have accepted the employment.”

Letters, written throughout 1887, point to a state of dissatisfaction and malaise of Hazrat Nuruddinra. His holy master, however, continues to pray and keeps him going.

Letters written in 1888 show Hazrat Nuruddinra still undergoing immense stress. Hazrat Ahmadas, on 5 January, expresses his concern and desire to visit Hazrat Nuruddinra in Jammu.

A letter of 22 January 1888 again carries advice and prayers for the tests and trials that Hazrat Nuruddinra is having to endure; another written on 22 February mentions financial hardships where he is having to borrow money.

These were the years when Hazrat Ahmadas was in the process of setting up his divine mission. He was constantly writing books for the defence of Islam and having them published. The cost of printing extensive material was hefty and Hazrat Ahmadas was considering having his own press installed in Qadian. Almost every letter carries mention of these expenses and gratitude for Hazrat Nuruddin’s generous contributions towards them.

A letter dated 29 February advises Hazrat Nuruddinra to stay away from debts and be very careful with his spending, using only a quarter or third of his earnings and saving the rest. Hazrat Ahmadas states:

“Be very careful with your spending as your earnings are important for our economy and bring for you a great deal of spiritual reward”.

This goes to prove that the pain and hardship of staying in an extremely hostile and unfavourable atmosphere was Hazrat Nuruddin’s sacrifice for his faith. He remained a major contributor, surpassing all other members of the then small community of Hazrat Ahmadas in financial offerings.

Hazrat Ahmadas had announced in late March 1889 the formal inauguration of the Ahmadiyya Community by taking the oath of initiation from those that had accepted his claims and were ready to be counted among his community. A letter of Hazrat Ahmadas, dated 20 February 1889, indicates that the said time was not suitable for Hazrat Nuruddinra to travel for the said purpose. It reads:

“The dates announced in the tract Takmil-e-Tabligh are only administratively suitable […] and not obligatory. You are allowed to attend for this ceremony when you have the time and when there are no obstacles.”

This letter from February 1889 coincides with the conspiracy hatched against the Maharaja in relation to the letters to the Tsar. It was a difficult time not only for the Maharaja but all the state staff; not to mention those accused of being his “favourites”. Hazrat Nuruddin’s reluctance seems to be due to the grave allegations brought against the Maharaja and his close associates.

However, Hazrat Nuruddinra managed to attend the initiation ceremony on 23 March 1889 and to return to Jammu; to find out that the Maharaja had become defunct and the State Council had completely taken over all administrative affairs. Hardship awaited him. Durand’s letter of 1 April 1889 had ordered the Resident that the government did not want to leave Kashmir “in the hands of Punjabi foreigners” and that he should “ascertain requirements of the State with regard to subordinate services and should submit for the approval of the Government […] as to the steps to be taken for reorganising the administrative services.” (National Archives of India, Lansdowne Papers, Durand to Nisbet, 1 April 1889)

Letters written to him by Hazrat Ahmadas point to a new surge of disturbance and distress that awaited Hazrat Nuruddinra in Jammu. On 21 March 1891, he is consoled in the following words:

“Your employment is of a great benefit to us. Its exterior may seem worldly but intrinsically, it is all for the faith.

“Although there is a great conflict going on, there seems to be divine wisdom behind you being stationed at such a place.”

The situation continued to deteriorate and on 16 August 1891, he is told:

“It is quite natural for jealousy to exist in worldly affairs […]. May God’s protection and favour be with you. It is without a doubt that such matters are perilous […]

“You are at an advance level of camaraderie and morals and mellowness, and I hope that you will demonstrate the same with your enemies and the envious; and that you shall abstain from interfering in affairs of the state.”

In the meantime, in 1891, the Maharaja was reinstated partially back to power. By this time, the game of betrayal and conspiracy had got to the extent where the Maharaja was no longer sure who was trustworthy and who was not.

Advice and consolations continue to go out to him from Hazrat Ahmadas until, finally, in August 1892; Hazrat Nuruddinra is expelled from his employment by the State Council. We gather this from Hazrat Ahmad’s letter dated 26 August:

“Having received your letter yesterday, I was left astonished. But then my heart opened up: This is another test from God, the Omniscience, the Merciful. God willing, this is nothing to fear. It is from Allah the Almighty’s ways of love that He tests His believers […]

“I cannot see why such harsh orders have been issued. How unfortunate is a state where the blessed and fortunate and truthful are driven out. Who knows what might happen next.”

Behind the scenes

The worries and sorrows of Hazrat Nuruddinra have been mentioned above. It would be a grave injustice to not mention how this great man continued with his duties and other virtuous acts as all this happened around him.

From his biographical accounts, we can infer that he was engaged in three major activities:

1. Treatment of the Maharaja, his relatives, as well as that of the underprivileged class. He occupied himself selflessly during the days of the great famines of Kashmir and those of cholera outbreaks.

2. Learning anything new that he could get his hands on. He mentions very fondly of learning Ayurvedic medicine from a Pandit Harnamdas. From Jammu, he wrote to German scholars of the Arabic language to enquire what books are best for learning Arabic and received their replies. He sponsored a group of young men to learn languages for the cause of the propagation of Islam.

3. Practicing and propagating the teachings of Islam. He takes pride in mentioning having taught some courtiers and even Raja Amar Singh some parts of the Holy Quran. He was known as an exemplary scholar of Islam in not only the State of Kashmir but all over India. He would travel to places to deliver lectures and would be highly commended.

While all the palace conspiracies went on and it became more and more difficult for him to stay in the hostile atmosphere, he remained steadfast in his faith and was widely known for doing so.

Amir Nisar Ali Shuhrat, editor of Rozan-e-Punjab and formerly head of the education department in Jammu, wrote a letter to the Civil & Military Gazette about Muslims in Kashmir and testified that:

“I have often said my prayers with Moulvie Noor-ud-din, the Durbar Physician, where they have loudly and freely called their Azan. Had it been forbidden by the Durbar, the said Moulvie would not have openly ventured to do so.” (Civil & Military Gazette, Lahore, 7 March 1889)

During these turbulent days, he delivered lectures on Islam to large gatherings of Muslims. Civil & Military Gazette, reporting on the annual convention of the Anjuman-e-Himayat-e-Islam, said:

“At 2 p.m. Hakim Nuruddin of Jamu delivered a long lecture in vernacular on the present condition of the community at large, and assured his hearers that so long as the Muhammadans remained firm in their devotion to the law of the prophet and loyal to the British Government they need have no fear as to their future success in life.” (Civil & Military Gazette, Lahore, 25 February 1890)

Even in 1892, when his agony in the service of the State of Kashmir was at its height, Hazrat Nuruddinra was busy lecturing about the teachings of Islam. A report from Civil & Military Gazette states:

“Moulvi Noor-ud-din, physician to H. H. the Maharajah of Kashmir, gave a philosophical lecture on Islam to a very large audience at Raja Dian Singh’s Haveli on the night of the 8th instant. The lecture commenced at half past 7, and lasted till half past eleven.”

It appears that he was travelling with the Maharaja’s entourage who were visiting Lahore on the same dates. The news story immediately above this one mentioned the Maharaja visiting the Punjab Chief Court, Lahore on the same date as the lecture of Hazrat Nuruddin. (Ibid)

It is clear from his accounts that he would make generous contributions towards the Muslim cause wherever he deemed it useful. Amongst his beneficiaries were the likes of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, Anjuman-e-Himayat-e-Islam and, of course, Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas of Qadian.

From Hazrat Ahmad’s letters addressed to him, it is seen that Hazrat Nuruddinra helped a large number of people in gaining employment in the State of Kashmir, even in the days when he himself was under immense pressure and his own employment dangled in uncertainty.

He summed up four deficiencies of states that function under absolute rulers:

1. The more ignorant the courtiers, the higher the chances there are of them gaining greater influence.

2. The rulers never let the bureaucracy work in peace and keep moving them around. This results in unrest and trust can never be developed between the ruler and his administrative staff.

3. Courtiers and ministers, owing to uncertainty, tend to get greedier so as to make the most out of their time in a certain position.

4. The government’s residents are conveyed mixed messages, which result in the resident’s mistrust in the ruler.

We can see from the entire story narrated in the above pages, that these points are derived from the experiences that Hazrat Nuruddinra endured during his state service in Kashmir.

He maintained good relations with everyone around him, regardless of whether this goodwill was reciprocated or not. He fondly mentions a few names that he spent time with in his Jammu years: Sheikh Fateh Muhammad, Gobind Sihai, Diwan Lachman Das, Raja Moti Singh of Poonch etc.

All of these men underwent hardships at the hands of the British Resident and his cronies i.e. the members of the State Council.

First of all, Lachman Das, the prime minister, was fired (The Englishman, 23 September 1885); the same happening to his successor, Gobind Sihai. (The Pioneer, 21 October, 1886; Minutes of meeting between the Maharaja and the Viceroy, Lord Dufferin, National Archives of India, Foreign Department, Progs, Sec E, December 1886)

The rest of the benefactors of Hazrat Nuruddinra, himself included, have already been mentioned in the list of persona non grata issued and signed by Raja Amar Singh and his associates.

The private servants of the Maharaja were a thorn in Plowden’s flesh ever since he had assumed office and was desperate to get rid of them at any cost. He wrote to the Foreign Department that if he could have them depart, “even on leave on [their] own accord, it will be a great gain.” (NAI, DP Reel 530, Plowden to Durand, 8 August 1886)

Some of these persons – once the blood and soul of an intellectually rich darbar – left on their own accord while some decided to cling on for as long as they could. Hazrat Nuruddinra was one of the latter. He had wanted to leave since 1885 but stayed behind on instructions of his master. In his autobiography, he recalls how once someone advised him to quit and leave. He replied by referring to the teachings of the Holy Prophetsa of Islam that it was not a good deed to abandon a source of livelihood for no good reason. His employment was not only a source of livelihood for him but also a source of the funds that supported the budding mission of his master, Hazrat Ahmadas.

When the Maharaja was deposed, the two new members added to the council were Suraj Kaul and Bhag Ram. (India Office Records, L/2/1073/194, Constitution of the Council, Folio 193)

Various departments were delegated to all four members of the council, with Suraj overseeing Revenue and Finance. With his newfound power, Suraj Kaul accused the “favourites” of the Maharaja’s court to be defaulters of huge amounts of money. This was the “Baqidar question” that loomed the latter days of Hazrat Nuruddinra in state service.

Hazrat Nuruddinra recalls that in the final days, Bag Ram, the fourth member of the Council and, naturally, a confidant of the Resident approached him and advised him to resign. Hazrat Nuruddinra replied in the negative as he placed teachings of Islam above personal pain or gain.

However, he was soon to be informed that he had been dismissed from state service and was ordered to leave Kashmir.

Although we do not find direct reference to this accusation of default in his autobiography, but a statement therein does lead us to assume a correlation. He states that he was “in debt of 195,000 rupees” at the time of his departure from Jammu.

Hazrat Nuruddinra had maintained cordial relations with the Maharaja as well as with Raja Amar Singh. Hazrat Nuruddinra states that Suraj Kaul – who wanted him out of the darbar by hook or by crook – took leverage of this and incited the Maharaja against him; the brothers were, after all, rivals in the game of power.

But this is Hazrat Nuruddin’s own assumption, about which he states:

“I do not have full knowledge [of what happened], but there are strong hints to suggest so.”

Later on, and a few lines down the same page, he mentions how the Maharaja – who had by then been reinstated – felt hurt at the pains that Hazrat Nuruddinra had went through and invited him to join the state service again.

Hence, as is quite evident from the documents quoted above, it is more probable that the State Council, including Raja Amar Singh, were and had always been against Hazrat Nuruddinra. The Maharaja was flustered by the then situation and was happy to sign anything that could save the gaddi that he had been reinstated to.

However, Hazrat Nuruddinra had to leave Jammu. He never took it personally. When the Maharaja later apologised for the wrongdoings against Hazrat Nuruddinra, he replied:

“It was a crime against God the Almighty and only God can forgive it. What is there in man’s power?”

He departed from the worldly kingdom that was plagued with greed, intrigue, deceit and conspiracy. He moved to the place that he had actually been groomed by God to live in. He lived the rest of his life in Qadian where he was to be enthroned as a caliph of the heavenly kingdom established by his master, Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas, the Promised Messiah and Mahdi.

The only character that appears to be remorseful is none else but the Maharaja who later arranged for Hazrat Nuruddin’s debt of 195,000 rupees to be paid off.

Was Hazrat Nuruddinra a spy?

While we are discussing the Jammu years of Hazrat Nuruddinra, it seems appropriate to address an allegation that has been levied against him by the opponents of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community.

Some say he was spying for the British government in Kashmir. Others say he was working as an agent with Russian authorities at the behest of the Maharaja.

As for spying for the British, the allegations can be found in anti-Ahmadiyya material written in the form of casual and passing statements. Such works in the Urdu language are Rafiq Dilawari’s Aima-e-Talbis and Rais-e-Qadian. No reference has been cited and the allegations have been imposed in casual and passing statements.

An English language work to insist on such claims is a book titled “Ahmadiyya Movement: British-Jewish Connections” by a Bashir Ahmad. This work, although garbed as an academic work by citing references, is published by no established publisher but by an Abdur Rashid of Islamic Study Forum, Rawalpindi. This work was published in 1994.

The author mentions Hazrat Nuruddinra as a “shrewd and clever person” before stating that “the Hakim kept a close watch on the bear hugs of Ranbir Singh who aspired to get rid of British domination in collaboration with the Czarist Russia.” (Bashir Ahmad, The Ahmadiyya Movement: British-Jewish Connections, Islamic Study Forum, Rawalpindi, 1994, p. 60)

He then goes on to mention two missions to Russia by Maharaja Ranbir Singh. He rightly mentions the names of persons involved, i.e. Sarfraz Khan, Abdur Rehman Khan, Baba Karam Parkash etc, but fails to cite any source to prove Hazrat Nuruddin’s involvement. To sound credible, he refers to Devandra Kaushir’s work Central Asia in Modern Times but fails to link it to his allegation against Hazrat Nuruddinra. Having read through Kaushir’s work, nothing has been found that links these missions to Hazrat Nuruddinra; on the contrary, a link even to the Maharaja is not established. General Chernayev, who received these missions in Russia, denied their claims to be representing the Maharaja as both the missions could not provide any proof of being so; the authorising letter, these delegates said, had been lost on the way. (Devandra Kaushir, Central Asia in Modern Times, Moscow, 1970, p. 104; National Archives of India, Foreign Department, Secret E, Pros April 1889, titled “Affairs of the Kashmir State. Discovery of treasonable letters.”)

Bashir Ahmad, having conveniently forgotten that he had, on just the opposite page, tried to prove Hazrat Nuruddinra to be an agent of the Maharaja in Russia, goes on to state:

“Nuruddin exerted considerable influence over Amar Singh. He convinced him that collaboration with the British was a prerequisite to attain power. Nuruddin also hatched another plot which was meant to establish British control in Kishtwar but the plan was subsequently dropped by the British Political Department.” (Bashir Ahmad, The Ahmadiyya Movement: British-Jewish Connections, Islamic Study Forum, Rawalpindi, 1994, p. 61)

For this self-contradicting statement, he cites as reference Rafiq Dilawari’s tabloid book, Aima-e-Talbis – the earlier mentioned casual and bias-laden work with no reference to any source whatsoever.

Since both statements contradict each other, there is no need for further comment. Bashir Ahmad, in his religious bias, presented his wishful thoughts as historical facts. Also, from the detailed discussion in this article has shown, from original sources, that Hazrat Nuruddinra was trusted neither by Raja Amar Singh (who signed the petition declaring him persona non grata), nor by the British Residents, who always sought ways of ousting him out of the system through any possible means.

The only work by a Western academic carrying this allegation, that I have been able to find, is titled Victoria’s Spymasters: Empire and Espionage by Stephen Wade. He writes:

“[…] before the Arab Bureau was in place, a group of Indian spies working for the British were in Egypt being sent there on a mission by Hakim Nuruddin, a doctor and court physician at Kashmir. Hakim worked with British political officers in the Raj from 1870, when he arranged for spies to travel to Tashkent and find out what diplomacy was going on regarding Russians.” (Stephen Wade, Victoria’s Spymasters: Empire and Espionage, The History Press, 2009)

Without providing any reference, Wade shamelessly moves on to narrating stories from history as if he was an eyewitness and his mere narration of events should suffice as credible testimony. The whole book is completely devoid of any citations. The once professor at the University of Hull should have known that such books might earn a bit of money and cheap fame, but never find a standing in the academic world; a hefty bibliography at the end of the book is no proof of any claims made therein.

Wade’s intellectual dishonesty also goes to show how publishers can be completely negligent of their responsibilities only at face value; although the author and his publisher, both seem to be devoid of any face value either.

What has given this baseless allegation currency for anti-Ahmadiyya writers and journalists in the Urdu language is Qudrutullah Shahab’s memoir-style autobiography, titled Shahabnama. While Shahab – a bureaucrat of Pakistan – is known for twisting facts and presenting lies as truth to fit his storyline, we can understand his underlying impetus behind him venturing on this allegation.

Shahab was a pseudo-mystic who gained following in the intellectual circles. He was very successful to have gained followers like Bano Qudsia and Ashfaq Ahmad. Not all intellectuals were under his spell and the liberal minded see him as an opportunist and a turncoat. (For a better understanding: Akhtar Abbas, From Bhutto to Zia to Musharraf, The Daily Dawn, 2 January 2016)

Before moving on, we need to see how opportunist literati (ironic as the term might sound) like Qudratullah Shahab mushroomed the literary scene of Urdu literature. To avoid giving my personal statement (that could be seen as biased), I present below an extract from international political analyst Ayesha Siddiqa’s enlightening piece:

“General Ziaul Haq’s military regime needed to take all sects, particularly, Sunni schools, on board. While the Deobandi and Ahl-Hadith were provided the shoulder of the state to grow, recruit men and fight its wars, the Barelvis and those subscribing to Sufi Islam were also kept close to the bosom. This was the period when the state discovered men like Tahirul Qadri. Intellectually, Zia encouraged the Qudratullah Shahb-Ashfaq Ahmed-Mumtaz Mufti gang to turn into vendors of a specific narrative […]

“During the 1980s, General Zia’s information secretary Lt. General Mujeebur Rehman acted as the Joseph Goebbels to alter the intellectual discourse into developing its distinctive Islamic and nationalist character. This was a period when the stock of not just the Qudratullah Shahab gang rose but also that of fiction writers like Sharif Husain alias Naseem Hijazi and Inayatullah Altamash.” (Dr Ayesha Siddiqa, Old Men’s Tales, www.drayeshasiddiqa.com, accessed 13 December 2021)

We move now to Shahab’s statement about the topic at hand:

“Maharaja Partab Singh was issueless, so he adopted a boy from his clan. But Raja Amar Singh, father of Hari Singh, could not accept this for he had desired his son to be the heir of the State. To fulfil this desire, he laid a net of conspiracies all over the State. In doing so, he was immensely assisted by Hakim Nuruddin.” (Qudrutullah Shahab, Shahabnama, Sang-e Mil Publications, Lahore, p. 358)

Again, his casual memoirs have misconstrued a supposed fact; no reference, no source, no person cited. Had he lived in Kashmir in the years that he mentions (1885-1892), one could still give his statement a second thought. But this statement is a crossbreed of wild imagination and intellectual corruption – no wonder, he was a mushroom in Ziaul Haq’s kitchen garden and had to live up to his master’s agenda.

Also worth noting is that Hazrat Nuruddinra here is portrayed as neither spying for the British, nor the Russians and for no one for that matter. He is shown conspiring with Amar Singh; the same Amar Singh who wanted him out of Kashmir at any cost.

The allegation of being a spy to be levied against such a great scholar and spiritually exalted personality is most definitely unfounded. I conclude here and let the inconsistencies and discrepancies in all such allegations speak for themselves.