Fazal Masood Malik and Farhan Khokhar, Canada

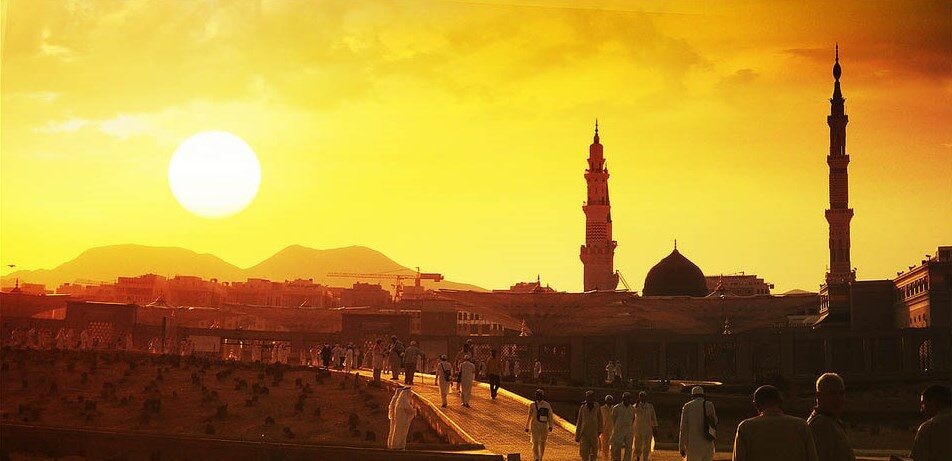

The Arabian Peninsula

The sixth century CE witnessed wars that directly affected the Arabian Peninsula. They brought about the fall of Himyar in the South, weakening the Persian and Byzantium empires in the North and this political instability favoured Mecca.

The oases surrounding Mecca paled compared to the quantity of water available in Medina, an agricultural city about 400 kilometres north of Mecca. However, Mecca soon grew into a city at the crossroads of several critical trade routes and a water filling station. Another factor that helped Mecca grow was the unassuming camel.

Around 500 BC, camel breeding started emerging as a profitable trade in Arabia. Perhaps owing to the efficient utilisation of water by a camel, it became a very profitable partner in trading (Judges 6:3-5). Seven centuries later, in 137 CE, the short-lived Palmyrenes imposed taxes on products brought to their territory using wheeled carts. This tax helped flourish their long-distance trading position and, in the process, Mecca, being the watering station in a merciless desert, became a thriving trading city. (Richard Bulliet, The Camel and the Wheel)

While the people of Mecca supported the trade between Nabateans, Palmyrenes and finally the Byzantium empires, they were not trading partners. Out of necessity, however, they dealt with local trade, which, together with its status as an idol worship centre, gave rise to the fortunes of Meccan traders. In these oasis settlements, the Bedouin came to trade milk, clarified butter, wool, hides and skins from their flocks for grains, dates, oil, clothing, wine and other items.

At the time of the birth of the Holy Prophet Muhammadsa, Mecca was Western Arabia’s most prosperous town. In addition to being a hub of the region’s lucrative trade routes, it was also a pagan sanctuary. Mecca had become a vital link between Byzantium and India in the preceding centuries. (Daniel Lerner, Passing of Traditional Society, p. 405)

Islamic Economy is based on the Holy Quran. And the Holy Quran tells us that the life of the Holy Prophetsa reflects the Holy Quran (Surah al-Najm, Ch.53: V.2-4) – a fact that is further supported by the testimony of his wife, Hazrat Aishara. When asked about the character of the Holy Prophetsa, she enquired, “Have you not read the Quran?” to which the enquirer replied, “Of course.” Hazrat Aishara responded, “Undoubtedly, the character of the Prophetsa of Allah was the Quran.” (Sahih Muslim)

Life at Mecca

The Holy Prophetsa was in his early teens when the Battles of Fijar (the sacrilegious) took place. They were so named because they took place during the pre-Islamic holy months, violating the societal norm. Shortly after the battles were over, a momentous event took place that speaks volumes about the character of this noble Prophetsa.

When peace was restored after these wars, people felt the need to restore confidence in the Meccan market – an effort that is reflected in the current world as well. The Holy Prophetsa facilitated the formation of a confederacy that would look after the rights of the weak and ensure contracts were honoured (Ibn Saad’s Kitab al-Tabaqat al-Kabir, Vol. 1, Parts 1.32.2, 1.33.1, 1.33.2, 1.33.3). This confederacy became known as Hilf al-Fudul. The oath that he took in his youth held merit until his last breath, even when the markets were fully established under the teachings of the Holy Quran.

The trustworthiness and honesty of the Holy Prophetsa were witnessed and held in esteem by all the tribes that existed in Mecca before Islam. One such trader was Hazrat Khadijara, an independent woman with an entrepreneurial spirit who worked tirelessly towards building her merchant business.

She did not travel with her trade caravans. Instead, she employed agents who would trade on her behalf for a commission. In 595 CE, she employed Muhammadsa, who was a young man of 25 years at the time and who had already earned a reputation as a trustworthy tradesman. His reputation led Hazrat Khadijara to offer him double her usual commission. She was rewarded well for her trust when Muhammadsa brought back twice as much profit as was expected. (Ibn Saad’s Kitab al-Tabaqat al-Kabir, Vol. 1, Parts 1.34.2-1.35.2).

Impressed by his honesty and integrity, she sent for his hand in marriage, which the young merchant duly accepted. Hazrat Khadijara became the first wife of the Holy Prophet Muhammadsa and is a shining example for all Muslims till the end of time.

By the time the Holy Prophetsa received his first revelation in 610 CE, he had about two decades of commercial experience behind him. While the next 13 years in Mecca are devoid of significant economic activity that involved him and his followers, it was during this tenure that the ethical fibre of social and economic dealings formed. It was during the Meccan period that the instruction to observe charity was given (Surah al-Dhariyat, Ch.51: V.20, Surah al-Ma‘arij, Ch.70: V.25-26), but Zakat as an institution did not evolve (from the Quranic perspective) till 2 AH (Surah al-Baqarah, Ch.2: V.268-69).

Understanding the teachings of Zakat is crucial to understanding the building blocks of the Islamic economy. As a source of revenue for the state, it maintains the administrative supremacy of the state as well as provides funds for socio-economic projects.

Life at Medina

After the migration of the Holy Prophetsa to Medina, the first Islamic state was established. The state is significant because it established the mosque as an institution and founded markets on ethical norms. There existed no formal political state in the Arabian Peninsula at the time. The Prophetsa thus became the first political leader, elected democratically, who established a multi-religious and multi-cultural state in Medina. It was a welfare state that addressed the needs of all its citizens, be they Muslims, Jews, Christians or of no faith. This event occurred in 1 AH (622 CE).

With the establishment of a state, the foundations of the Islamic economic teachings started to solidify. The emphasis on charity and almsgiving was established during the Meccan period. Still, there was no central body to collect and distribute the funds. In Medina, a complete framework of a functional economic system emerged. This system included economic components dealing with ownership and consumption, production, distribution, social security, economic development, public finance and the Bayt al-Maal.

In 1 AH (622 CE) Medina, numerous markets existed with no cohesion or central rule to mitigate their behaviour. The Constitution of Medina sought a peaceful coexistence and played a vital role in establishing market stability. While the Muslims were still trying to establish themselves, they were forced into a battle. On route to the battlefield, the economic condition of Muslims was so precarious that the Holy Prophetsa had to pray, “O Allah, these people are on foot, give them to ride upon. O Allah, these people are naked, give them clothes. O Allah, these people are hungry, feed them to the fill.” (Abu Daud)

Another hardship factor faced by the Muslims was that of industry. While Mecca’s economy was a trade economy, Medina was an agrarian society.

Perhaps the most significant first step towards establishing a prosperous state was ensuring political, social and economic stability. The path towards the development of the Constitution of Medina was proof for all parties involved that peace can be sought through consultation. It was this respect that contributed to the development of a central authority.

The state that evolved was mindful of its citizens regardless of their religious and cultural beliefs. It was a welfare state that looked after the needs of its citizens and, at the same time, built alliances with the neighbouring tribes. Despite the constant threat from Mecca, this stability was crucial in the establishment of a thriving economy.

Islam encourages the establishment of a free market with high ethical standards; a market free of external pressure and based on moral values, thus creating the conditions needed to create a prosperous life for its citizens, a stable society and fulfilling the spiritual aspect of its consumers. (Surah al-Nisa, Ch.4: V.30)

A few centuries later, Imam al-Ghazalirh noted, “Let the souk [market] of this world below do no injury to the souks of the Hereafter, and the souks of the Hereafter are the mosques.”

The Holy Prophetsa, being an excellent merchant, understood the workings of the market. His emphasis on a free market was such that while drought was devastating the community in Mecca, he advocated against price-fixing: “The Musa‘ir [He who sets prices] is Allah.” (Tirmidhi)

While this principle advocates free-market capitalism, it falls under a strict ethical injunction of the Holy Quran: “And give full measure when you measure, and weigh with a right balance; that is best and most commendable in the end.” (Surah Bani Isra‘il, Ch.17: V.36)

Further, the prohibition of hoarding and interest encourages investment that binds all parties to work towards the success of the venture. It essentially creates conditions for the proper functioning of a competitive market as an instrument of economic progress and social equity.

In the following articles, we discuss the ethics of the Islamic Economy, the institution of bait-ul-maal (treasury), the sources of revenue in early Islam and the distribution methods.