Friday Sermon

26 December 2025

Muhammadsa: The divine bond of love

After reciting the tashahhud, ta‘awwuz and Surah al-Fatihah, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih Vaa stated:

In the previous sermon, I mentioned some aspects of the life of the Holy Prophetsa. Today, I will discuss some aspects of his life in relation to his love for Allah the Almighty. Some of these aspects may have already been briefly discussed in the past. However, some of them will be discussed in detail today.

In relation to this aspect of the life of the Holy Prophetsa, the love Allah the Almighty had for the Holy Prophetsa also becomes manifest. It was not only that the Holy Prophetsa loved Allah the Almighty, but Allah the Almighty also loved him. Furthermore, after Allah the Almighty manifested His love for the Holy Prophetsa, He also guided him. We see how the Holy Prophetsa increased in this love and ensured the moral training and guidance of his Ummah [nation]. We observe how he conveyed to his Ummah the teachings that Allah the Almighty revealed to him so that they can be guided. The heart of the Holy Prophetsa was full of anguish and yearning for this. In fact, it was this very anguish due to which Allah the Almighty Himself guided him, as he was to guide the Ummah. In other words, on the one hand, his heart was filled with anguish for the love of Allah the Almighty, and on the other hand, it was filled with pain and yearning for the creation of Allah the Almighty and a longing to save them from destruction.

In the Holy Quran, in Surah ad-Duha, Allah the Almighty says:

وَوَجَدَکَ ضَآلًّا فَھَدٰی

“When He found you wandering about, concerned for your people, He taught you the correct methods for their reformation.” (93:8) Furthermore, in relation to his love for Allah the Almighty, the translation of this verse is as follows. Allah the Almighty says: “And We found you wandering in anguish in search for our love, and so we directed you towards that path by which you found your way to Us.”

In Tafsir-e-Kabir of Imam Razirh, the following is written under the commentary of this verse of Surah ad-Duha:

وَوَجَدَکَ ضَآلًّا فَھَدٰی

“One meaning of ‘daall’ is love, as is mentioned by Allah the Almighty in the verse:

اِنَّکَ لَفِیْ ضَلٰلِکَ الْقَدِیْمِ

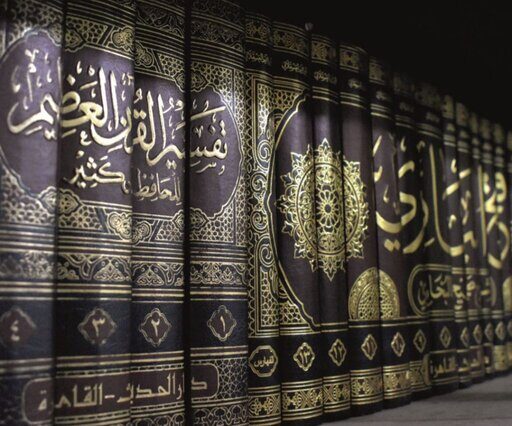

“The word ‘daall’ here means love. Thus, the meaning will be that you are a beloved. As such, I guided you to such paths which will enable you to gain nearness [to God] by serving your beloved.” (Mafatih-ul-Ghaib, Al-Tafsir Al-Kabir, Vol. 16, Tafsir Surah ad-Duha, V. 7, Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyah, Beirut, 2004, p. 197)

Through this, Allah the Almighty has testified that the Holy Prophetsa is completely immersed in His love.

We find this expression of love in various narrations; the love of Allah the Exalted for the Holy Prophetsa and his love for Allah the Almighty. The Promised Messiahas states at one place:

“Anyone well-versed in the modes of expression of the Noble Quran will not fail to recognise that, at times, the Most Gracious and Merciful, Exalted be His Majesty, employs words for His chosen servants that may appear unflattering on the surface, but in meaning, they are highly praiseworthy and commendatory. (On the surface, if we look at the general use of the word, it seems that it is not the appropriate word, as the word ‘daal’ means misguidance. However, this is not so. When Allah the Almighty uses it for His chosen servants on a particular occasion, the meaning of the word changes.) For example, Allah, glorified be His eminence, said regarding His Noble Prophet:

وَوَجَدَکَ ضَآلًّا فَھَدٰی

“[‘And He found thee wandering in search for Him and guided thee unto Himself.’ (93:8)]

“Obviously, the well-known and familiar meaning of the term ‘daall’, which the linguists are also fond of citing, is ‘astray’. According to this understanding, the verse would mean, ‘(O Messengersa of Allah!) God Almighty found you misguided and guided you’ (this is how the common people translate it), whereas the fact is that the Holy Prophet, may peace and blessings of Allah be upon him, was never misguided. Anyone who professes to be a Muslim yet believes that the Holy Prophetsa was engaged in an act of misguidance at any point in his life, is a kafir [disbeliever], devoid of faith, and deserving of punishment under Islamic law.

“Here the verse should be assigned a meaning consistent with the context, which is the following: Allah, glorified be His eminence, first stated about the Holy Prophet, may peace and blessings of Allah be upon him:

اَلَمۡ یَجِدۡکَ یَتِیۡمًا فَاٰوٰی وَوَجَدَکَ ضَآلًّا فَہَدٰی

“Meaning that: God Almighty found you an orphan and helpless, and He gave you shelter with Himself and found you ‘daall’ (meaning that deeply in love with the Countenance of Allah), and therefore He drew you towards Himself and He found you indigent and enriched you. (93:7-9)” (Aina-e-Kamalat-e-Islam, Ruhani Khazain, Vol. 5, pp. 170-171 [The Mirror of the Excellences of Islam, pp. 148-149])

The Promised Messiahas further states:

“As the Holy Prophetsa was higher than all the other Prophets in the purity of his soul, the expansion of his mind, his chastity, modesty, sincerity, trust, fidelity and love of the Divine, God, the Glorious, anointed him with the perfume of special excellence in excess of any other Prophet. His inner and heart, which was broader and holier and more innocent and brighter and more loving than the chest and heart of any who had passed before him, and who were to come after him, were considered worthy that such Divine revelation should descend upon him as should be stronger and more perfect, higher and more complete, than the revelation vouchsafed to all those who were before him and all those who were to come after him, and which should serve as a clear, wide and large mirror for reflecting Divine attributes.” If one looks into this mirror, then one can see the attributes of Allah the Almighty as well as every aspect of Allah the Almighty. This can also be seen in the life of the Holy Prophetsa and in the teachings he brought.

The Promised Messiahas states:

“That is why the Holy Quran possesses such high excellences that the brightness of all previous books is cast into the shade before its fierce and brilliant rays. (Meaning all the light and eminence of the previous scriptures hold no value before it.) No mind can put forth a verity which is not already contained in it (everything is found in the Holy Quran). There is nothing that a person can create or invent which has not been mentioned already in the Holy Quran. Indeed, one needs to understand it.) And no reason can present any argument which is not already presented in it. No speech can affect the hearts so powerfully as the strong and full-of-blessings effect it produces upon millions of hearts. Undoubtedly, it is a clear mirror reflecting the perfect attributes of the Divine in which all is found that is needed by a seeker to arrive at the highest grades of understanding.” (Surma-e-Chashm-e-Arya, Ruhani Khazain, Vol. 2, pp. 71-72 [footnote])

Thus, the teaching that was revealed to the Holy Prophetsa was itself so pure that it stood above all things, above all teachings, and loftier than all scriptures. The Holy Quran contains a complete and perfect teaching. Therefore, the being of the Holy Prophetsa is the embodiment of that teaching; that is to say, his being too was complete and perfect, and this is something he demonstrated. The Book that was revealed to him was revealed for this very reason, that his being is the most perfect of all human beings, and he alone is that perfect man whose rank cannot be attained by anyone. Indeed, Allah the Almighty has declared that the Holy Prophetsa is an excellent model; strive so that you follow him. This is why, through the Holy Prophetsa, Allah the Almighty made this proclamation that people should be informed:

قُلْ اِنْ کُنْتُمْ تُحِبُّوْنَ اللّٰہَ فَاتَّبِعُوْنِیْ یُحْبِبْکُمُ اللّٰہُ وَیَغْفِرْلَکُمْ ذُنُوْبَکُمْ وَاللّٰہُ غُفُوْرٌ رَّحِیْمٌ

“Say, ‘If you love Allah, follow me: then will Allah love you and forgive you your faults. And Allah is Most Forgiving, Merciful.’” (Ch. 3: V. 32)

Thus, the ways of attaining the love of Allah the Almighty must also be learnt solely from the excellent model of the Holy Prophetsa. The manifestations of his love for Allah the Almighty that we observe are recorded in the Hadith; many such narrations are found in which the Holy Prophetsa, yearning for the love of his God, would offer the following supplication:

اَللّٰهُمَّ إِنِّي أَسْأَلُكَ حُبَّكَ، وَحُبَّ مَنْ يُحِبُّكَ، وَالْعَمَلَ الَّذِيْ يُبَلِّغُنِي حُبَّكَ، اَللّٰهُمَّ اجْعَلْ حُبَّكَ أَحَبَّ إِلَيَّ مِنْ نَفْسِيْ وَأَهْلِيْ وَمِنَ الْمَاءِ الْبَارِدِ۔

“O Allah, verily I ask You for Your love and the love of those who love You, and for the action that will cause me to attain Your love, O Allah, make Your love more beloved to me than myself, my family and cold water.” (Jami‘ at-Tirmidhi, Kitab ad-da‘wat, Hadith 3490)

Thus, today, this is the supplication that every person who claims to have love for the Holy Prophetsa ought to recite and who desires that he too becomes beloved to Allah the Almighty and for Allah the Almighty to bestow His grace upon him. Likewise, it is narrated in a tradition that Hazrat Abdullah bin Yazid Khatmi Ansarira relates that the Holy Prophetsa used to supplicate:

“O Allah, grant me Your love, and grant me the love of that person whose love will benefit me in Your presence. O Allah, whatever beloved things You grant me, make them a means of strength for me in attaining those things that are beloved to You; and whatever beloved things You take away from me, make them a means of strength for me in attaining those things which You love.” (Jami‘ at-Tirmidhi, Kitab ad-da‘wat, Hadith 3491)

Therefore, the Holy Prophetsa prayed that whatever beloved things You grant me, make them a source of strength for me in pursuit of the things beloved to You; grant me further strength so that as I acquire more of those things, I become beloved to You, and through them I attain even more of Your love and come to acquire those things that You like.

And he further prayed that whatever dear things I have – things which I consider dear to me, or my loved ones – but which You separate from me, then make them for me a means of strength in attaining those matters which You hold dear. Do not make those things that have been taken away become a cause of despair; rather, I should thereafter receive renewed strength, since Allah the Almighty did not like them and separated them from me, or since this was the will and pleasure of Allah the Almighty, then may those things which Allah the Almighty loves be granted to me. O Allah, if You take away from me those things which You do not like, then grant me the strength to attain those things which are beloved to You and are pleasing to You. Hence, this was an expression of his love for Allah the Almighty.

Similarly, Hazrat Aishara relates that after the revelation of اِذَا جَآءَ نَصْرُ اللّٰہِ وَالْفَتْحُ, the Holy Prophetsa did not offer any prayer in which he did not say:

سُبْحَانَکَ رَبَّنَا وَبِحَمْدِکَ اَللّٰھُمَّ اغْفِرْلِیْ

“Holy are You, O our Lord, and with Your praise; O Allah, forgive me.” (Sahih al-Bukhari, Kitab at-tafsir, Hadith 4967)

Hazrat Aishara has described an incident demonstrating love for Allah the Almighty in the following words:

“I was sleeping beside the Messengersa of Allah when, during the night, I did not find him there. In the darkness of the night, I felt around for him, and my hand touched his feet. He was in prostration, supplicating to Allah the Almighty: ‘I seek refuge in Your pleasure from incurring Your displeasure, and I seek refuge in Your pardon from incurring Your punishment. I cannot enumerate Your praises; You are as You have praised Yourself.’” (Sahih Muslim, Kitab as-salat, Hadith 743)

That is to say, I am not able to praise you in a manner that truly behoves Your high status, except through the praise that You Yourself have mentioned concerning You – that alone is Your true praise.

Likewise, at another place, Hazrat Aishara states:

“One night, it was the turn of the Holy Prophetsa to stay at my house. I fell asleep, and he quietly went outside. I assumed that perhaps he had gone to one of his other wives. Overcome by a sense of great indignation, I came out and what did I behold? The Holy Prophetsa was prostrating upon the ground, folded like a bundle of cloth. I heard him supplicating:

سَجَدَلَكَ سَوَادِي وَخَيَالِي وَآمَنَ بِكَ فُؤَادِي رَبِّ هَذِهِ يَدي، وَمَا جَنَيْتُ عَلَى نَفْسِي، يَا عَظِيْم تُرْجَى لِكُلِّ عَظِيْمٍ فَاغْفِرِ الذَّنْبَ الْعَظِيْمَ

“‘O Allah, my body and soul are prostrated before Thee; my heart believes in Thee. O my Lord, these are my two hands stretched forth before Thee, and whatever wrong I may have committed against my own soul is before Thee.’”

The Holy Prophetsa was such a perfect human being that nothing could be perceived of him except piety, yet even he would say, “Whatever wrong I have done to my own soul lies before Thee. O Possessor of supreme greatness, from Whom every great matter is expected, forgive all the greatest sins.”

Hazrat Aishara further relates that “He then raised his blessed head and saw me, and said, ‘What made you come out?’ (Why did you come outside? You were asleep.) I submitted, ‘Because of the thought that came to my mind,’ meaning, ‘I thought you had gone to one of your other wives.’ He said, ‘Indeed, some assumptions can become sins. Did you harbour doubt about me? That is a sin.’”

As Hazrat Aishara had stated that she doubted whether he had gone to another wife, he explained that such suspicions become sins and one should seek forgiveness from Allah. Thus, to safeguard oneself from ill suspicion, it is essential in every matter to seek forgiveness from Allah the Almighty and to engage in istighfar (seeking forgiveness from Allah).

The Holy Prophetsa then said to Hazrat Aishara, “The fact is that Gabriel came to me and instructed me to recite these words; therefore, you too should recite them in your prostrations. Now that you have heard them, recite them. Whoever recites these words will be forgiven before raising his head from prostration.” (Majmu Al-Zawaid, Kitab-ul-Salat, Hadith 2775, Vol. 2, Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyah, Beirut, p. 259)

Provided that they truly believe in Allah the Almighty, possess perfect faith, and is also one who performs other righteous deeds. He said this to Hazrat Aishara because he knew her high spiritual standard. It does not mean that one who neglects other good deeds may merely recite these words and be forgiven.

Similarly, another narration states – reported in greater detail in Sahih Muslim – that Hazrat Aishara said: “One night, when the Holy Prophetsa was staying with me, he returned home, placed his cloak aside, removed his shoes and placed them near his feet, spread a corner of his upper garment on the bed, and lay down. When he thought that I had fallen asleep, he quietly took his cloak, quietly put on his shoes, opened the door, and went out, then gently closed the door.

“I took my veil and upper garment and followed him until he reached Jannat al-Baqi. He stood there for a long time in supplication, then raised both his hands three times, and then turned back. I also turned back. He quickened his pace, and I quickened mine. He walked faster, and I did likewise. Then he returned home, and I entered before him and lay down. When he came in, he said, ‘O Aisha, what is the matter with you? Why is your breathing heavy?’ My breathing had become heavy due to walking quickly, and the Holy Prophetsa noticed it. I said, ‘Nothing,’ trying to evade the matter. He said, ‘You must tell me. Otherwise, the Subtle and All-Aware God will inform me.’ I said, ‘O Messengersa of Allah, may my parents be sacrificed for you,’ and then I told him everything – what had crossed my mind and how I had followed him.

“The Holy Prophetsa said, ‘So it was you – the shadow I saw ahead of me.’ I replied, ‘Yes.’ He then tapped my chest with his hand in a manner that I felt, and said, ‘Did you think that Allah and His Messengersa would wrong you?’” Hazrat Aishara said, “Whatever people conceal, Allah surely knows it. Indeed, Allah the Almighty knows it and would have disclosed it to you; therefore, I told you myself what was in my heart.”

The Holy Prophetsa said, “When you saw me going outside, it was Gabriel who had come to me and summoned me. Since he kept this matter concealed from you, I accepted his instruction and kept it concealed from you as well. That is why I did not inform you and went with him. I thought you had fallen asleep, and I disliked waking you. I also feared that you might feel lonely, thinking that you were left alone if I had told you.” He further said, “Gabriel told me that your Lord commands you to go to the people of Baqi‘ and seek forgiveness for them.”

Hazrat Aishara says that she submitted, “O Messengersa of Allah, how may I also share in this reward? What prayer should I offer for them? You have already prayed for them, but I have also come from there, so what should I pray?” The Holy Prophetsa said, “Say: ‘Peace be upon the inhabitants of this abode from among the believers and the Muslims. May Allah the Almighty have mercy upon those of us who have gone ahead and those who will come later, and insha-Allah, we too shall join you.’” (Sahih Muslim, [Urdu translation], Vol. 4, Kitab al-jana’iz, Hadith 1607, Noor Foundation Rabwah, pp. 138-140)

Thus, he taught this supplication as well.

Similarly, in relation to the love of the Holy Prophetsa for Allah the Almighty, Atta relates: “I, along with Hazrat Abdullah bin Umar and Ubaid bin Umair, came into the presence of Hazrat Aishara. Hazrat Ibn Umar said, ‘Tell us of the most beloved and wondrous matter that you observed in the Messengersa of Allah.’” The narrator stated, “Upon hearing this, Hazrat Aishara began to weep and said, ‘Every matter of his was beloved and wondrous.’ She then related that ‘once, on a night when it was her turn [for the Holy Prophetsa to stay at her house], the Holy Prophetsa came to her. When he entered the quilt with her and his body touched hers (she felt his body close to hers), he said, “O Aisha, if you permit me, I would spend the remainder of this night in the worship of my Lord.”’ She replied, “I love your closeness, and I love your wish as well. (I cherish your nearness and respect your desire). What I love most is that all your wishes are fulfilled. If you desire to worship, then do so.” He then went to a waterskin kept in the house and performed ablution, using only a small amount of water. He then stood and began reciting the Quran and weeping until I saw that his tears reached his garment. Then he lay on his right side, placing his right hand beneath his cheek, and again began to weep, until I saw that his tears fell upon the ground. Then Hazrat Bilalra came to inform him, as it was the time for the Fajr prayer. When he saw him weeping, he submitted, “O Messengersa of Allah, are you weeping when Allah Almighty has forgiven all your past and future sins?” He replied, “Should I not then be a grateful servant?” (Akhlaq-ul-Nabi Wa Aadabahu, Hadith 553, Dar-ul-Lu’Lu, Cairo, 2016, pp. 408-409)

I mentioned the Holy Prophet’ssa quality of gratefulness in the last sermon, and its further details are as follows:

In another narration, Hazrat Aishara states that whenever the Holy Prophetsa saw clouds or strong winds, concern would become apparent upon his face. She said, “O Messengersa of Allah, when people see clouds, they rejoice, hoping for rain, but I observe that whenever you see clouds, concern appears upon your face.” He replied, “O Aisha, how can I be assured that it does not contain a punishment of a destructive wind? I do not possess knowledge of the unseen. What could assure me that it does not carry the punishment that befell earlier nations? An earlier nation once saw the punishment and said, ‘This is a cloud that will bring rain upon us,’ (as mentioned in the Holy Quran). Therefore, I do not know what it contains or does not contain, and due to my fear of Allah Almighty and my love for Him that resides in my heart, I become apprehensive.” (Sahih al-Bukhari, [Urdu translation], Vol. 12, Kitab-ul-Tafsir, Hadith 4829, Nazarat Ishaat, Rabwah, pp. 68-69)

In another narration, Hazrat Aishara relates the same incident in these words: “Whenever the Holy Prophetsa saw clouds gathering in the sky, he would become restless and go to and fro, entering and leaving his house repeatedly, and his blessed countenance would change. When the clouds finally began to pour rain, his anxiety would leave him, and he would return to a state of calm.”

Hazrat Aishara once asked the Holy Prophetsa the reason for this state of uneasiness. The Holy Prophetsa replied, “I do not know whether these clouds are like the ones seen by the people of ‘Ad, who, as mentioned in Surah al-Ahqaf, saw clouds advancing towards their valleys and said, ‘These are clouds that will bring us rain,’ whereas in truth, they brought upon them a punishment.” (Sahih al-Bukhari, [Urdu translation], Vol. 6, Kitab Bud’i l-khalq, Hadith 3206, Nazarat Ishaat, Rabwah, pp. 29-30)

Another narration records that Hazrat Abu Hurairahra said: “The Holy Prophetsa and his Companions, when the first drops of rain fell, would uncover their heads so that the rain might touch them, and the Holy Prophetsa would say, ‘This has come to us fresh from our Lord, and it is full of blessings.’” (Kanz-ul-Ummal, Vol. 1, Kitab al-azkar, Auqat-ul-Ajabah, Hadith 4936, Dar Al-Kotob Al-Ilmiyah, Beirut, 2004, p. 267)

When ordinary rain fell, this too was among his practices.

‘Urwah bin Zubairra relates that he once asked Hazrat ‘Abdullah bin ‘Amr bin al-‘Aasra, “Tell me of the worst treatment that the idolaters ever inflicted upon the Holy Prophetsa.”

He replied, “Once, the Holy Prophetsa was offering prayer inside the Hatim of the Ka‘bah when ‘Uqbah bin Abi Mu‘it came and threw his cloth around the Prophet’ssa neck and began to strangle him. Just then, Hazrat Abu Bakrra arrived, seized ‘Uqbah by the shoulder, pulled him away from the Holy Prophetsa, and said, ‘Do you strike a man only because he says, “My Lord is Allah”?’” (Sahih al-Bukhari [Urdu translation], Vol. 7, Kitab Manaqib al-ansar, Hadith 3856, p. 332)

He is overwhelmed with the love of Allah and engaged in His worship, yet you are bent upon harming him!

The entire life of the Holy Prophetsa was immersed in the love of God. It was the spectacle of this divine love that led the people of Mecca to say:

اِنَّ مُحَمَّدًا عَشِقَ رَبَّہُ

“Indeed, Muhammadsa has become the lover of his Lord.” (Imam Ghazali, Al-Munqidh min al-Dalal, Dar-ul-Minhaj, 2015, p. 107)

The Promised Messiahas states:

“The Holy Prophetsa was an ardent and passionate lover of the One God, and in that love he attained what no one else in the world has ever attained. His love for Allah was so deep that even ordinary people would say:

عَشِقَ مُحَمَّدٌ عَلٰی رَبِّہٖ

“‘Muhammadsa has fallen in love with his Lord.’” (Malfuzat, 2022, Vol. 6, p. 6)

The Promised Messiahas also stated:

“The Companions, may Allah be pleased with them, had beheld the countenance of that true one, whose being the lover for Allah was so spontaneously testified to even by the disbelieving Quraish. These people, observing his daily supplications, his loving prostrations, his condition of complete obedience, the bright signs of perfect love and devotion on his countenance, and witnessing divine light raining down upon his face, were compelled to say that:

عَشِقَ مُحَمَّدٌ عَلٰی رَبِّہٖ

“This means:

“Muhammadsa is passionately in love with his Lord. Moreover, the Companions observed not only that devotion, love, and sincerity, but matching this love – which surged up in the heart of our lord and master Muhammad, peace and blessings of Allah be on him, like a raging ocean – they also observed God Almighty’s love for him, in the form of extraordinary support and help. Thus they realised that God exists, and their hearts testified aloud that God is with this man. They saw divine wonders to such an extent and witnessed heavenly Signs to such a degree that they were left with no doubt whatsoever that there does, indeed, exist a Supreme Being whose name is God, who controls everything and for whom nothing is impossible. That is indeed why they exhibited such deeds of devotion and sincerity and made such sacrifices as are not possible for anyone to perform until all doubts and suspicions have been removed. They saw with their own eyes that the pleasure of that Holy Being lies only in embracing Islam and adopting the obedience of His Noble Messengersa with heart and soul. After this absolute certainty, the kind of obedience that they exhibited and the feats they performed and the manner in which they laid down their lives at the feet of their holy guide.” (Shahadatul Quran, Ruhani Khazain, Vol. 6, p. 346 [Testimony of the Holy Quran, pp. 79-80])

Such accomplishments are not possible without first-hand experience.

Hazrat Alira relates:

“I once asked the Holy Prophetsa about his way of life – what was his fundamental principle. He replied, ‘Divine cognisance is my capital.’”

That is to say, when asked what his way of life was and upon what principle his existence was based, the Holy Prophetsa said, “Divine cognisance is my wealth, and wisdom is the foundation of my faith. The knowledge of God that He has granted me is my treasure, and the intellect He has bestowed upon me, I employ in His love and according to His revealed guidance. This is the essence and foundation of my faith, and the love of Allah is the very basis of my life.”

He continued, “The desire to advance in the path of God is my mount. In His love and on His path, I move ever forward. This yearning is my steed, upon which I am always progressing and striving. The remembrance of Allah is my companion and my comforter. My true friend, my comforter, and the one who soothes my heart is none other than the remembrance of Allah and prayer. Trust in Allah is my treasure. I rely only upon Him, and that reliance is my wealth.

“This is the way of life that you enquire of. Know that grief and sorrow are my companions. When pain or hardship comes my way, they are a part of my life, and I do not mind them, for Allah the Almighty is with me.” He further said, “Knowledge is my weapon. Allah has commanded the acquisition of knowledge, for it enlightens the mind and increases one’s awareness of God. It is Allah the Almighty Himself who grants me knowledge, and what weapon could be greater than that which comes from God? This is my weapon, by which I attain progress.”

Even in worldly matters, as seen in the accounts of battles mentioned previously, Allah granted him such knowledge that his planning and strategy were of the highest order. Likewise, his spiritual knowledge was vast beyond measure, clear and manifest to all.

He further said, “Patience is my cloak.” Meaning, his garment (as it were) was patience. “Contentment with the will of God is the spoil of battle for me. I remain content in the pleasure of God. Poverty is my pride; even if it seems apparent that I am poor or deprived of wealth, I take pride in that. I take pride in the fact that despite this state of poverty, Allah the Almighty had blessed me beyond measure. Abstinence is my skill. Piety and self-restraint are my art, and I strive to perfect it. Certainty is my strength. Complete faith in Allah is the source of my strength. Truthfulness is my intercessor. I have never spoken falsehood, and truth itself is my means of intercession. Obedience is sufficient for me. I act in complete obedience to Allah the Almighty’s every command. Jihad is [the foundation of] my character. Whether it is physical striving, spiritual striving in the way of Allah, or fulfilling the rights of God’s creation, this underpins my moral character. The delight of my eyes is in prayer. Although all these qualities are part of my being, the true comfort of my eyes lies in prayer, in attaining nearness to Allah the Almighty, in worshipping Him, and in expressing my love for Him.”

In another hadith, he said, “The fruit of my heart is in the remembrance of Allah, and my longing is in my Lord.” (Al-Shifa bi Ta‘eef Huqooq Al-Mustafa, Qadi Ayyad, Hadith 347-348, UAE, 2013, p. 191)

I have presented only a few examples of the model established by the Holy Prophetsa and his example of love for Allah the Almighty. It was this very example that brought about a revolutionary change among the Companions, enabling them to achieve a rank which had previously been inconceivable. As the Promised Messiahas has stated – in the quote which I presented earlier – it was this very complete and perfect teaching which the Ardent Devotee of the Holy Prophetsa, the Promised Messiahas also emulated. At one instance, the Promised Messiahas states that Allah the Almighty bestowed His favours on him by virtue of his complete obedience to the Holy Prophetsa. The Promised Messiahas states:

“On two occasions, Punjabi half-verses have been communicated to me. I have just described one occasion:

جے تو میرا ہو رہیں سب جگ تیرا ہو

“[If you will be devoted to Me, the whole world will be yours] and the other was that I saw a vast field in which a majzub (i.e., a person completely absorbed in the love of God) was advancing towards me. When he arrived close to me, he recited:

عشق الٰہی وَسّے مُنہ پر ولیاں ایہہ نشانی

“[A saint is recognised by the shining of Divine love on his countenance.]” (Tadhkirah [English], pp. 609-610)

The meaning of this vision shown to the Promised Messiahas was that the man saw the Promised Messiahas and said this because he saw the light of Divine love in the Promised Messiahas. At another instance, the Promised Messiahas also said that everything he had attained was on account of his obedience to the Holy Prophetsa. (Haqiqatul Wahi, Ruhani Khazain, Vol. 22, p. 64)

Hence, this was his example, and this is why the Promised Messiahas established this Jamaat. Today, we who proclaim to be the true followers of the Holy Prophetsa, and by pledging allegiance at the hand of the true and ardent servant of the Holy Prophetsa, we have reaffirmed our pledge to live our lives in accordance with the commandments of God Almighty, we must therefore pay great attention towards this in that we must carry out every deed with utmost sincerity for the sake of Allah the Almighty and to strive in excelling in our love for Him. It is only when we do this that we can become the recipients of Allah the Almighty’s blessings; do true justice to being a part of the Ummah of the Holy Prophetsa; and do true justice in our pledge of allegiance to the Promised Messiahas and be counted amongst his true followers. May Allah the Almighty grant us the ability to do this.

Pray for the Ahmadis in Pakistan. Two days ago, in a court case that was ongoing regarding Mubarak Sani Sahib, the session judge sentenced him to life imprisonment. The accusation levelled against him is that he had a copy of the Holy Quran in his possession, which he would recite himself and teach it to others as well. When this is the state of the courts, then what hope can there be of any improvement in the situation? Even the non-Ahmadis have expressed their opinions upon this decision and have labelled it as a mockery [of the justice system]. Although the clerics are generally applauding this decision and praising the judge, the fair-minded people have written, and some have commented on this in a sarcastic manner, that this was such a huge “crime” in that he recites the Holy Quran and has kept a copy of it in his home and teaches it to children? In any case, this is the state of the so-called scholars and their followers. In some places, the administration of the government is following these clerics and implementing their policies. We pray that Allah the Almighty creates the means for them to be swiftly seized. Insha-Allah, Allah the Almighty will swiftly seize them, and we can even witness signs of it unfolding as well. But we should be concerned lest there is a delay in this owing to any negligence on our part in terms of our supplications, practical conduct and fulfilling the due rights of worship, just like the Holy Prophetsa would look up at the clouds and out of the same concern would make this prayer.

Thus, there is a great need to pay close attention to prayers. Likewise, pray for the oppressed people of the rest of the world as well, that Allah the Almighty may grant peace to everyone, everywhere, and protect all from every form of disorder and turmoil.

After the prayer, I will lead two funeral prayers in absentia, both of which I will mention. The first is of Maulana Jalaluddin Nayyar Sahib. He was the former Sadr Sadr Anjuman Ahmadiyya and Sadr Majlis Tahrik-e-Jadid Qadian. He recently passed away.

اِنَّا لِلّٰہِ وَاِنَّآ اِلَيْہِ رٰجِعُوْنَ

[“Surely, to Allah we belong and to Him shall we return.”]

His father, the respected H Hussain Sahib, served as a clerk in the army during World War. During this period, in 1922, while stationed in Basra, he accepted Ahmadiyyat and was appointed editor of the Jamaat magazine Sathiya Dooton, published from Kerala. He was originally from Kerala and returned there after leaving the army.

In 1950, H Hussain Sahib hearkened to the call of Hazrat Musleh-e-Maudra regarding the scheme for the resettlement of Qadian and moved there to settle permanently with his entire family. However, within one year, he passed away in Qadian. Thereafter, Maulana Jalaluddin Nayyar Sahib’s mother, Zubaida Sultana Sahiba, remarried in Qadian to Chaudhry Abdul Haq Sahib, who was a dervish. He took responsibility for the upbringing of Nayyar Sahib’s brothers and sisters.

Maulana Jalaluddin Nayyar Sahib received his early education in Qadian, and in 1963, he passed the examination for Maulvi Fazil. He was then appointed initially to serve in the Anjuman as Inspector Bait-ul-Maal for a long period, during which he toured Jamaats across India. Through tireless effort and sincere affection, he brought members of the Jamaat into the system of financial contributions. As a result, he developed personal relationships with Jamaat members all across India.

The late Nayyar Sahib was granted the opportunity of serving the Jamaat for 63 years. After serving as Inspector Bait-ul-Maal Aamad, he later served as Auditor, then as Muhasib, and subsequently for a long period as Nazir Bait-ul-Maal Aamad. As mentioned earlier, he was appointed Sadr Sadr Anjuman Ahmadiyya Qadian for seven years, and then he also served as Sadr Majlis Tahrik-e-Jadid for as long as his health permitted.

Similarly, he was granted opportunities to serve in the auxiliary organisations as well. He was a devout worshipper, regular in fasting and prayer, and was counted among those foremost in obeying every directive of Khilafat. He was also a sportsman and an athlete, and in this regard, too, he organised extensive activities there.

He was married into a family from Kashmir. His wife passed away before him. He is survived by two sons and one daughter, all of whom are serving the Jamaat. May Allah the Almighty grant him forgiveness and mercy.

The second mention is of respected Mir Habib Ahmad Sahib, son of Mir Mushtaq Ahmad Sahib. He recently passed away at the age of 79.

اِنَّا لِلّٰہِ وَاِنَّآ اِلَيْہِ رٰجِعُوْنَ

[“Surely, to Allah we belong and to Him shall we return.”]

He was extremely kind-hearted, sociable, and deeply devoted to Khilafat. By the grace of Allah the Almighty, he was also a musi. Ahmadiyyat was established in his family through his grandfather, Bau Abdul Rahim Sahib, who accepted Ahmadiyyat in 1903 through Hazrat Mir Qasim Ali Sahibra, Editor of the Faruq magazine. Hazrat Mir Qasim Ali Sahibra had adopted Mir Habib Sahib’s father, Mushtaq Ahmad Sahib, as he had no children of his own.

Mir Habib Sahib completed his FSc and BSc from Government College, Lahore, and subsequently obtained an MSc degree in Physics. He later went abroad as well. His Jamaat services include beginning his teaching career at Talim-ul-Islam College from 1970 to 1971, when the colleges had not yet been nationalised. From 1973 to 1976, he served in Sierra Leone under the Nusrat Jehan Scheme, where he was granted the opportunity to teach Physics in Freetown. He returned to Pakistan in 1976 but in the same year went back to Nigeria, where he worked in a government school until 1987. While in Africa, in 1987, he dedicated his life as a life devotee. That same year, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IVrh appointed him Principal of the Ahmadiyya Senior Secondary School, Hamrasha, where he served until 1991.

After that, he returned to Pakistan and continued serving the Jamaat there as well. In 1992, Hazrat Khalifatul Masih IVrh sent him to Sierra Leone to evaluate a technical institute, and based on his expert report, certain developments were carried out there. In 1996, under Nazarat Talim, he was appointed to the Nusrat Jehan Academy in Rabwah, where he served as a Physics teacher until his retirement. He also served in the office of Sadr Umumi and volunteered his services in the General Islahi Committee.

His wife writes that her husband was regular in fasting and prayer, extremely gentle in temperament, and never made demands. He had a deep love for reading and had a passion for pursuing knowledge. If someone asked what gift to bring him, he would say, “Bring me books,” and he would regularly read scholarly works. In the same way, he extensively studied the books of the Promised Messiahas.

He never made false statements. If there was something he did not wish to say, he would remain silent rather than speak incorrectly. His daughter has also mentioned these same qualities. I, too, observed him and found him to be a very noble individual who minded his own affairs and fulfilled his life devotion with complete faithfulness. May Allah the Almighty grant him forgiveness and mercy.

He was married to Syeda Lubna, the granddaughter of Mir Ishaq Sahibra and the daughter of Major Saeed Ahmad Sahib. Hazrat Mir Muhammad Ishaq Sahibra was the son of Hazrat Mir Nasir Nawab Sahibra, who is well-known within the Jamaat and whose translation of the Holy Quran is commonly used within the Jamaat. In any case, may Allah the Almighty grant the deceased forgiveness and mercy.

(Official Urdu transcript published in the Daily Al Fazl International, 16 January 2026, pp. 1-8. Translated by The Review of Religions.)