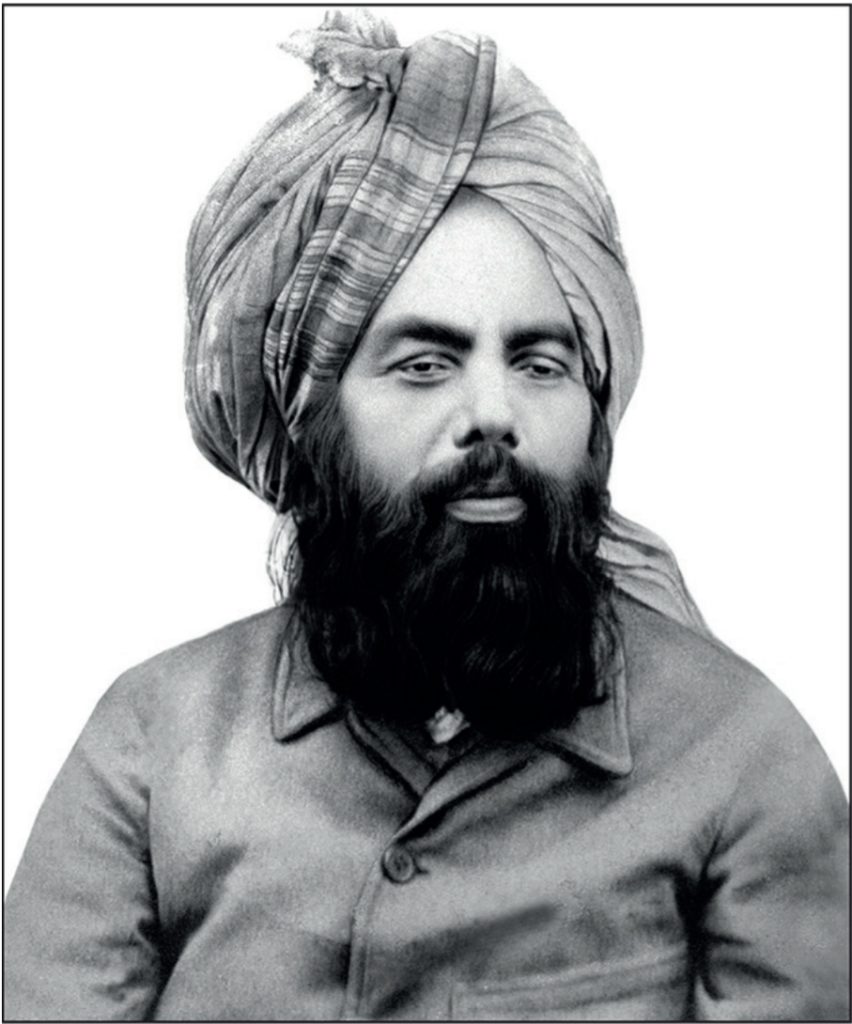

Shedding light on the claim of Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas with regard to his knowledge of the Arabic language, this series of articles seeks to answer major allegations raised against the Promised Messiah’sas use of Arabic phrases, his God-given eloquence and his command over the language and the usage of sentences taken from past literature.

Muhammad Tahir Nadeem, Central Arabic Desk

The importance of explaining the Arabic lughaat and its benefits

Explaining the benefits of variations between different lughaat, Allama Al-Suyutirh has quoted Ibn Janni’s statement in his book, Al-Muzhir. This statement holds great importance and is as follows:

اللُّغَاتُ عَلَى اخْتِلافِها كُلّها حُجَّةٌ

“Despite the fact that there are variations between different lughaat, every single one of them is hujjah [comprehensive evidence].” (Allama Al-Suyutirh, Al-Muzhir)

This means that if anyone, without having complete knowledge of each and every lughat, raises an objection to some of the words, phrases or styles in the writings of the Promised Messiahas after his claim to have been taught the Arabic lughaat by God Almighty, then their allegation would be considered null and void. Moreover, the scholars admit that all the lughaat have not been recorded and the number of lughaat that have been preserved is very small.

Now, as the Promised Messiahas claimed to have been taught 40,000 Arabic lughaat, it is quite possible that these lughaat included some that have not yet been recorded. Hence, if some pedantic individual finds such lughaat unfamiliar and objects to them, it will be a proof of their own ignorance.

After this explanation of the subject of Arabic lughaat, many words that appear in the books of the Promised Messiahas but are apparently considered wrong, are proved to be eloquent and their traces are found in the lughaat of the Arabs.

The Promised Messiahas claimed that he was given knowledge of various lughaat by Allah the Almighty. This miracle can be witnessed at numerous places in the Arabic works of the Promised Messiahas and the variations of these lughaat manifested in his Arabic books also serve as a proof of his absolute proficiency in God-given knowledge of Arabic.

Consequently, there are many examples of variations in the Arabic works of the Promised Messiahas. For instance, reducing hamzah and replacing it with ya, such as بريئون instead of بريّون and writing بير instead of بئر etc. The statement presented at the outset also indicates that despite these variations, it is an eloquent lughat.

In the same way, there are many examples in the works of the Promised Messiahas of using feminine and masculine forms according to the intended meanings of the words. For instance, addressing the Arabs, the Promised Messiahas wrote in his book Al-Tabligh:

يَا أَهْلَ أَرْضِ النُّبوَّةِ وَجيرانَ بَيْتِ اللّٰهِ العُظْمَى

“O dwellers of the land of prophethood and neighbours of the exalted House of Allah.” In this sentence, the Promised Messiahas has used the feminine form عظمي instead of masculine form عظيم for describing the quality of بيت which is masculine. The reason of using feminine form عظمي is that the Promised Messiahas meant الكعبة by بيت الله, which is feminine.

In his Arabic book, Al-Istifta, the Promised Messiahas states:

وَأَمَّا الآفَاتُ الرّوحانيَّةُ فَيُهْلكُ الجِسْمَ والرّوحَ والْإيمانَ مَعًا

“As for spiritual diseases or evils, they destroy the body, soul and faith, all together.” In this phrase, the masculine verb فَيُهْلكُ has been used for the word الآفَاتُ, which is feminine. The Promised Messiahas has used the masculine form of the verb for الآفَاتُ to refer to الشرّ (evil) or السمّ (poison), which are masculine.

In Khutbah Ilhamiyah [the Revealed Sermon], the Promised Messiahas said:

وَإِنَّ القَصَصَ لَا تَجْري النَّسْخُ عَلَيْهَا كَمَا أَنْتُمْ تُقِرُّونَ

“And certainly, these narrations are not subject to abrogation as you claim.” In this sentence, النسخ is masculine but intending it to mean عملية النَّسْخ(procedure of abrogation) or قاعدة النَّسْخ (principle of abrogation), the feminine verb تَجْري has been used for it.

As mentioned in the previous part of this article, one of the reasons behind the differences in the Arabic lughaat is taqdim and ta‘khir (exchange of sequence of letters in a word). For example, some people recite or write the word صاعِقة as صاقِعةٌ. Now, look at the following statement of the Promised Messiahas in his Arabic book, Hujjatullah:

وَلَا رَيْبَ أَنَّهُمْ هُم العِلَلُ الموجِبَةُ لِفِتْنَتِهِ، وَمَنْبتُ شُعْبَتِهِ، وَجرْمُوثَةُ شذْبَتِهِ

“Without a doubt, they are the flaws which cause him to fall into temptation, the source of its stem, and root of its tree stump.”

If another Arabic lughat is formed by changing صاعِقة to صاقِعةٌ due to taqdim and ta‘khir, then it can be assumed that it is not wrong to change جرثومة to جرْمُوثَةُ. Rather than considering this usage to be scribal error or a mistake, it may well be a correct usage of a specific lughat.

In the exchange of letters, some tribes used to exchange هwith ح in different words and vice versa. For example, in the book of lughat, Al-Mukhassas, it is stated that some people read:

كَدَحَهُ as كَدَههُ

يَهْتَبِش as يَحْتَبِش

الحَفيف as الهَفيف

أَهَمَّني الأمر as أَحَمَّني الأمر

قَمَحَ البعيرُ as قَمَهَ

طَحَره as طَهَرَه

and

مَدَحَه as مَدَهَه

It is further narrated that the Holy Prophetsa said to Ammarra: وَيْهَكَ ابنَ سُمَيَّة, but rather it should have been وَيَحَكَ. Wherever this hadith has been recorded, ح has been exchanged with ه in the word وَيَحَكَ, and it is one of the most eloquent lughaat. (Al-Mukhassas, Kitab al-Azdad, Bab ma Yaji‘u Maqulan bi Harfain wa Laisa Badlan)

Now, keeping the above-mentioned rule in mind, when we look at the Arabic books of the Promised Messiahas, we find that at certain places, he has written محجّة الاهتداء as مهجّة الاهتداء by exchanging ح with ه. Likewise, in his Arabic book, Hujjatullah, the Promised Messiahas has written the word حوجاء instead of هوجاء by exchanging هwith ح and this is considered an impressive style and a famous lughat of Arabs.

Similarly, many other ancient Arabic lughaat are found in the Arabic works of the Promised Messiahas that are extinct in today’s Arabic writings. Below are some examples:

1. In Arabic, unlike other languages, there are separate rules for singular and plural, as well as for referring to two things (i.e. Al-Muthanna). In Arabic, alif and nun come at the end of a word to show that it is Al-Muthanna (dual), when it is in a state of rafa‘a (nominative case). For example, the dual of جَنَّةٌ is جَنَّتَان, meaning two paradises or two gardens. When it is in state of nasab (accusative case) or jarr (genitive case), alif changes into ya, i.e. in accusative and genitive cases جنتان will be written as جنتين. The example of nominative case can be observed in the following verse of the Holy Quran:

وَ لِمَنۡ خَافَ مَقَامَ رَبِّهٖ جَنَّتٰنِ

“And for him who fears to stand before his Lord there are two Gardens.” (Surah al-Rahman, Ch.55: V.47)

The example of accusative and genitive cases can be observed in the following verse of the Holy Quran:

وَ اضۡرِبۡ لَهُمۡ مَّثَلًا رَّجُلَيۡنِ جَعَلۡنَا لِاَحَدِهِمَا جَنَّتَيۡنِ مِنۡ اَعۡنَابٍ

“And set forth to them the parable of two men: one of them We provided with two gardens of grapes.” (Surah al-Kahf, Ch.18: V.33)

Contrary to these rules, in the lughaat of some tribes such as Banu al-Harith Ibn Ka‘ab, Khath‘am, Zubaid and Kanana etc., the state of Al-Muthanna never changed in nominative, accusative or genitive cases. Its alif used to remain in all the three cases and was not changed with ya. (Al-Nahw al-Wafi, 1/123-24, and Jami‘ al-Durus al-Arabiyah li Shaikh Mustafa al-Ghalayini)

The examples of the Arabic lughaat with respect to Al-Muthanna are also found in the Arabic works of the Promised Messiahas, but some opponents, due to lack of knowledge, object when they find such examples contrary to today’s well-known rules. Below are some of those old lughaat and examples of the above-mentioned rule from the Arabic works of the Promised Messiahas:

[…] مِنْهَا أَنَّ الشُّهُبَ الثواقِبَ انْقَضَتْ لَهُ مَرَّتَانُ

“One such [sign] is that shooting stars which appeared twice for him.” (Al-Istifta)

أَلّا تَعْلَمونَ أَنَّ هَذَان نَقيضانِ فَكَيْفَ يَجْتَمِعَانِ فِي وَقْتٍ واحِدٍ أَيُّهَا اَلْغافِلونَ

“O those who are unaware, do you not realise that these two are complete opposites, so how can they come together at the same time?” (Al-Tabligh)

إِنَّ فِي هَذَا الِاعْتِقادِ مِصِيبِتَانَ عِظِيمْتَانِ

“Certainly, there are two great calamities in this belief.” (Ibid)

In all the above examples, Al-Muthanna, i.e. مَرَّتَانُ, هَذَان نَقيضانِand مِصِيبِتَانَ عِظِيمْتَانِ, is mansub (accusative) and as per general rules of Arabic grammar, it should have come with ya and nun at the end, but according to the old lughaat, it is correct.

2. The common rule for كلا and كلتا is that when they are mudaf (the noun that comes before ‘of’ and is possessed or owned) to an apparent noun, then in all three cases, their alif remain. However, deviating from this general rule, in the lughat of the tribe of Kanana, they are changed according to the common rule of Al-Muthanna in their respective cases. An example of this kind is also found in the Arabic works of the Promised Messiahas and it is as follows:

لِيَدُلّ لَفظُ الأُنسَين عَلَى كِلْتَيْ الصِّفَتَين

“The word al-unsain signifies both attributes.” (Minan al-Rahman)

The person who does not know this lughat will say out of ignorance that is should be كلتا الصفتين instead of كِلْتَيْ الصِّفَتَين, but his assertion is erroneous because this form is also part of Arabic lughaat.

3. One of the lughaat of the Banu Rabi‘ah tribe was that they did not write alif at the end of a word which was mansub (accusative) with tanwin (nunation). For example, they used to write قرأت كتابًا without alif as قرأت كتابً.

An example of this lughat is also found in the Arabic works of the Promised Messiahas. He stated:

وَتَتَعَهَّدها صَباحً وَمَساءً زُمَر الْمُعْتَقدينَ

“The group of believers make this pledge every morning and evening.” (Maktub Ahmad)

Instead of صباحًا, the Promised Messiahas has written صباحً, which is one of the old lughaat.

Apart from the above-mentioned variations, one of the causes of discrepancy in Arabic lughaat was that some tribes used to change some letters and use other letters in their place. For example, they used to read and write mim after changing nun. In this regard, the statement from Lisan al-Arab is as follows:

وَفِي كِتابِهِ لِوائِلِ بْنِ حجْرٍ: مَنْ زَنَى مِم بِكْر وَمَن زَنَى مِم ثَيِّب، أَيْ مِنْ بِكْرٍ وَمِن ثَيِّبٍ، فَقَلَبَ النُّونَ مِيمًا

“Wa‘il bin Hajjar has written in his book: ‘man zana mim bikrin wa man zana mim thayyib’, using mim instead of min, that is, he has changed the letter nun into mim.” (Lisan al-Arab, under the word mim)

Similarly, among other reasons for differences in the Arabic lughaat, the examples of changing different letters such as ghain to kha and jim to ha etc. are also present.

Hence, if these variations are kept in mind, a lot of objections of opponents will be answered automatically.

Somebody can object that all of our justifications and deductions cannot be considered correct, because the door of limitless usages devoid of rules cannot be opened on the basis of such assumptions. The opponents can say that such matters should be taken from the Arabs through discourse, that is, their usages should be allowed and other styles should not be used. The answer to this objection is that it is a well-known fact to the lexicographers that very little from the auditory lughaat of the Arabs has been preserved and a great deal has been lost.

Thus, none of the writings related to the subject of lughaat could be ruled out because they may well be one of the Arabic lughaat; especially if the author of such writings claims that he has been given the knowledge of Arabic lughaat by God Almighty, then this possibility turns into a certainty. Moreover, the out-of-the-ordinary Arabic works of the Promised Messiahas compel a person to believe that they are from the lughaat of the Arabs.

(Research conducted by Muhammad Tahir Nadeem Sahib, Arabic Desk UK. Translated by Al Hakam, with special thanks to Ibrahim Ikhlaf Sahib, Arabic Desk UK)