Asif M Basit, Curator Ahmadiyya Archive and Research Centre

The Taliban are back again. Most of Afghanistan is now under their control and the mantra of Islamic state, Khilafat and the-rule-of-Islam is being chanted once again – in tones that continue to grow louder.

While the media deal with the issue as one of current affairs, a quest for its historical roots is completely ignored; hence blocking off one of the most plausible routes towards resolving it.

The Indian mutiny in 1857 had a long history as well as long-lasting implications that have spanned over all the years and decades that have so far followed. While Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims all fought against the British, Muslims alone were singled out as “violent” and “militant” in their outlook about the British colonial rule. Not often mentioned is the role the British press played in fashioning Muslims as such.

One of the malicious outcomes of the 1857 mutiny was a vicious cycle where the British press would brand Muslims as rebellious and violent, and certain Muslim circles would retaliate to this allegation in, ironically, a “rebellious” and “violent” manner; hence providing the British press more ammunition to attack Islam and its notion of jihad. This then went on in cycles, becoming more aggressive with every rotation.

Serving the colonial agenda, the British press employed a systematic approach (typical to the Western press and media even in this day) in branding Muslims as more of a race than a religion and one with an extremely rebellious approach. WW Hunter’s book, Indian Musalmans works as a good example of this approach with even the title suggesting the marginalising approach adopted therein. Hunter’s conclusion could be summed up as: The majority of Indian Muslims are not “good Muslims”, are fanatically violent and thrive on their belief in “Jihad” which is incumbent upon them.

Muslims, on the other hand, adopted the approach (typical to the Muslim world to this day) of violent retaliation. The British, who were mostly Christians, did not have to do much to further vilify Islam as ample proof was dished out by the fanatic response of Muslims themselves.

Unfortunately, the Muslims had very few among them who could counter the British propaganda in the same battlefield with similar weapons i.e. through the press by using words.

The one person usually seen as the Muslim protagonist in such testing times is Sir Syed Ahmad Khan who wrote a detailed review of Hunter’s work. Despite being a good attempt at refuting Hunter’s generalised vilification of Islam, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s review remained a piece aimed at the British government and did no good to reforming the Muslim understanding of jihad.

Christian missionaries found Hunter’s work as a great tool to incite Muslims on carrying out their religious duty of “jihad” which Muslims responded to in a manner favourable to the former.

The only remedy to the situation could come through a double-edged approach: to reform the Muslim understanding of jihad in the given situation and, also, to inform the government and Christian missionaries that their approach of vilifying Islam was the primary motive behind the violent Muslim reaction.

This was to come through the works of Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas, who took upon himself to reconfigure the concept of jihad in the Muslim psyche and also to warn the government that provocative works of Christian missionaries were equally responsible for the insurgency witnessed in certain Muslim circles.

This approach of Hazrat Ahmadas makes his work “Jihad and the British Government” one of immense importance in getting to the roots of what we now see as global terrorism. To get an idea of this double-remedy, I quote two short passages from the above-mentioned work:

“It should be remembered that today’s Islamic scholars (who are called maulavis) completely misunderstand jihad and misrepresent it to the general public. The public’s violent instincts are inflamed as a result and they are stripped of all noble human virtues. This is in fact what has happened […]”

“O Muslim scholars and maulavis! Listen to me. I tell you truly that this is not the time for jihad. Do not disobey God’s Holy Prophet.”

“At this point I must with great regret say that although ignorant maulavis have instructed the ordinary public in plunder and killing by calling these actions jihad, Christian clerics have also done something similar. They have, in Urdu, Pashto and other languages, produced thousands of publications, journals and flyers alleging that Islam was spread by the sword. This literature has been distributed by them in India, Punjab and the Frontier Region, wrongly claims that Islam is synonymous with violence. The people’s penchant for violence has increased as a result of the combined testimony of the maulavis and Christian clerics. The dangerous lies of the Christian clerics create unrest and rebellion and, in my view, it is essential that our government prohibit them.”

Hazrat Ahmadas identified the North Western frontier of India and its neighbouring Afghanistan as the epicentre of the fanaticism exhibited in the name of Islamic jihad. Tapping on the root-cause, he saw Muslim maulavis and Christian clerics equally responsible for it as both highlighted jihad as being incumbent upon every Muslim against every disbeliever.

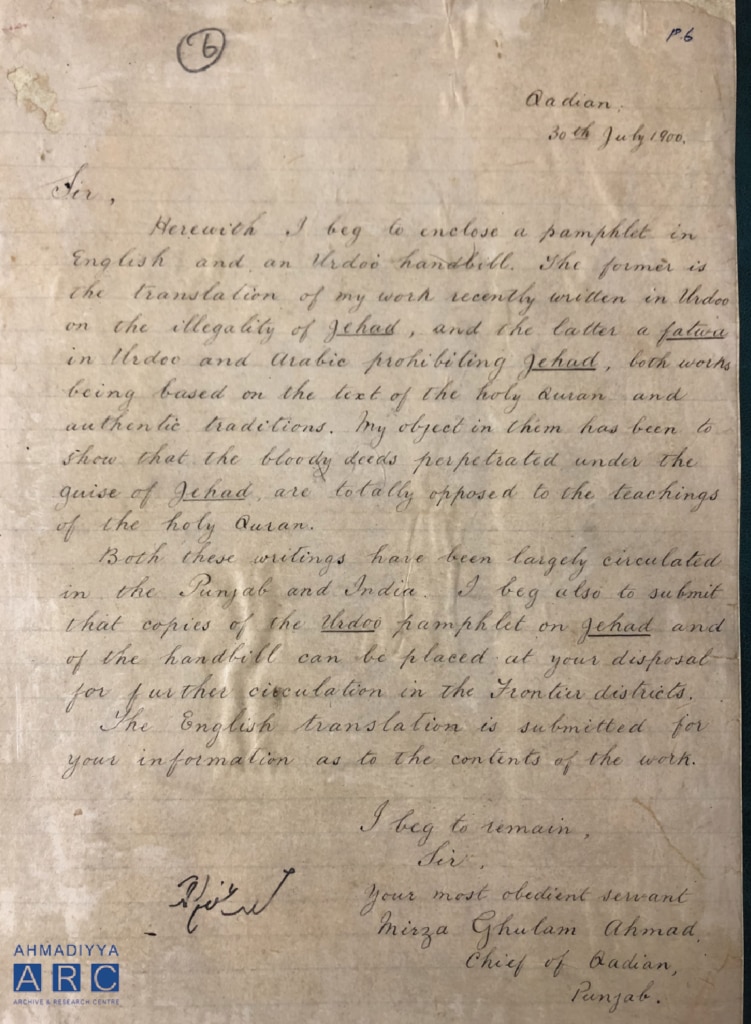

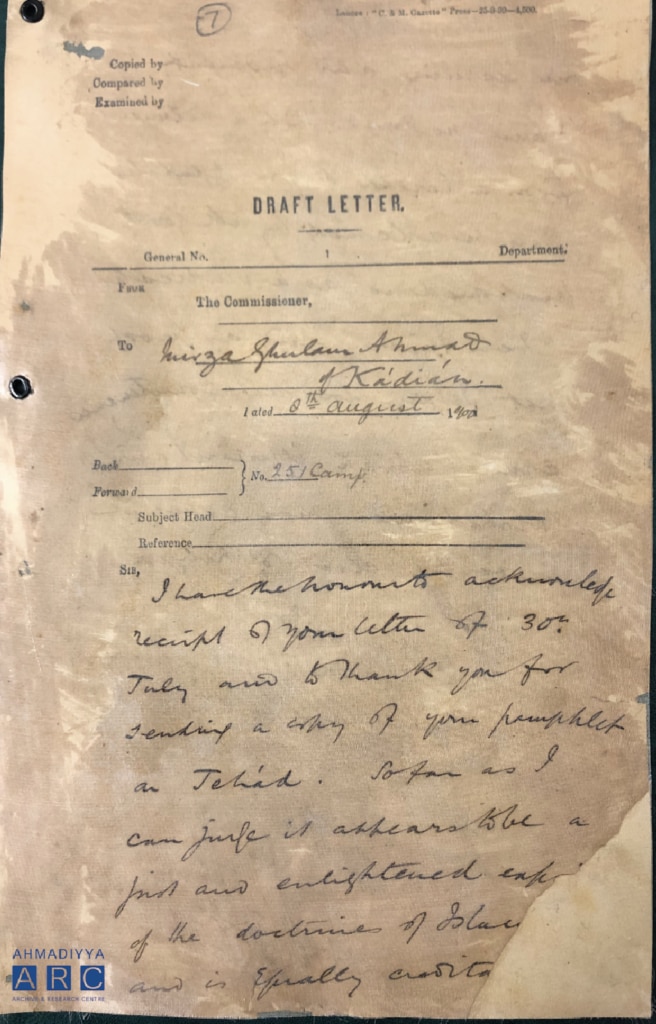

Hazrat Ahmadas wrote a letter to Francis Cunningham (the commissioner of Peshawar) informing him that the treatise, Jihad and the British Government had been written in Urdu for the general population to understand and had been distributed free of charge. He offered Cunningham more copies at his own expense to distribute in Peshawar, the frontier region and Afghanistan.

With the situation laid bare before the British government by Hazrat Ahmadas, one is left thinking whether the government even wanted the violence in the name of jihad to end; just as one is left thinking today whether the West actually wants the ongoing violence in the name of Islam end. It seems as if it suits some greater agenda of the West against Islam.

Very closely linked to the notion of jihad against disbelievers was the punishment for apostasy; the latter practised equally brutally by Muslims of the Frontier region and Afghanistan in the days of the British raj.

Abdul Latifra of Khost, who had remained a confidant of the Amir’s court in Kabul, happened to travel to India. He had remained instrumental in the Afghan delegation that held negotiations with the Durand commission during the demarcation of the Afghan border.

While in India, he met Hazrat Ahmadas and accepted his teachings. Upon return, he was charged with apostasy, imprisoned and finally stoned to death at the orders of the Amir of Kabul.

Hazrat Ahmadas was deeply hurt at this barbaric act and wrote a detailed treatise titled, Tadhkiratush-Shahadatain. He pointed out the fact that Kabul had turned into a place where the worst form of atrocity had been carried out in the name of Islam. He saw this act of violence as one that could be understood in isolated form and was to have greater implications in times to come. The warning, once again, was ignored by the authorities.

That the British government ignored clear and plain warnings by Hazrat Ahmadas is not a claim without proof. After the publication of Tadhkiratush-Shahadatain, newspapers like Akhbar-i-Aam and the Civil and Military Gazette published excerpts in their publications. The Amir of Kabul took notice and urged the British government that the account published by Hazrat Ahmadas was libellous and that charges of defamation be brought against him.

The lengthy correspondence between British-Indian government officials that entailed the Amir’s complaint sits in its original form in the Indian National Archives. Every piece of communication between the bureaucrats only seeks ways of how the Amir’s request can be politely declined. Attempts were also made to see if any steps could be taken against Hazrat Ahmadas so as to harbour diplomatic goodwill with the Amir. For instance, a letter from DE McCracken (assistant at headquarters to the general superintendent) to SE Wallace (assistant to the inspector-general of Police, Punjab), dated 14 January, 1904, states:

“I shall be much obliged if you can send me urgently any papers you may have on record relating to discussion of the point whether legal action could be taken against Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Kadian […]”

After much deliberation, the government could not find good reason to prosecute Hazrat Ahmadas, with Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India, writing to his officials the following on 2 February 1904:

“I should have thought that the best course was to say frankly to the Envoy [of the Amir] that the Amir had laid himself open to violent attacks by the murder of Abdul Latif […]”

The viceroy, being head of the British-Indian government, knew well about the fate that had struck Abdul Latif, yet no communication with the Amir of Kabul was made in this regard. To further confirm that the British government was aware of the atrocity carried out in the name of Islam, the aforementioned record – marked “SECRET” on almost every folio – has an extract from the “Diary of the British Agent at Kabul” (dated 15 July 1903):

“Mulla Abdul Latif having obtained permission had started on a pilgrimage to Mecca from Khost. But on his arrival in India he became a follower of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, Kadiani. Thereupon he altered his mind and returned to his province, and effected a change in the minds of the people of the province to a certain extent as to their religious creed. This matter was reported to the Kabul authorities. By order of the Amir he was arrested and brought in to the Darbar, in which all the Maulvis gave a unanimous opinion that both the Mulla and Ghulam Ahmad, Kadiani, were infidels. Under the orders of the Amir, Mulla Abdul Latif was stoned to death below the gallows. His remains were buried in that very place.”

The silence exhibited by the British government on the brutality of the Amir of Kabul in the name of Islam speaks volumes about where things initially went wrong. Historians can better decide whether the British diplomacy in the days of the Raj was correct or incorrect (politically and otherwise), but the statement uttered by Hazrat Ahmadas seems to have proven itself true – all along and to this very day:

“O land of Kabul, stay witness to the heinous crime committed on your soil. O unfortunate land, you have fallen in the estimation of God for being home to this extreme brutality.” (Tazkiratush-Shahadatain)

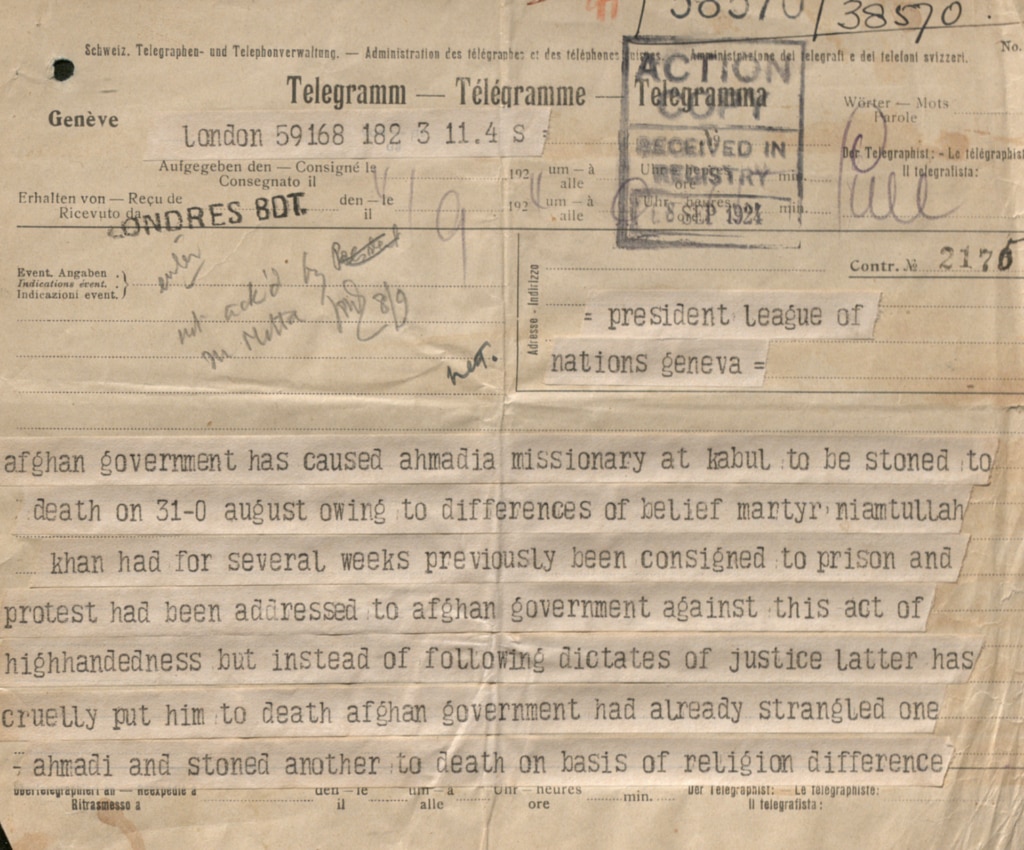

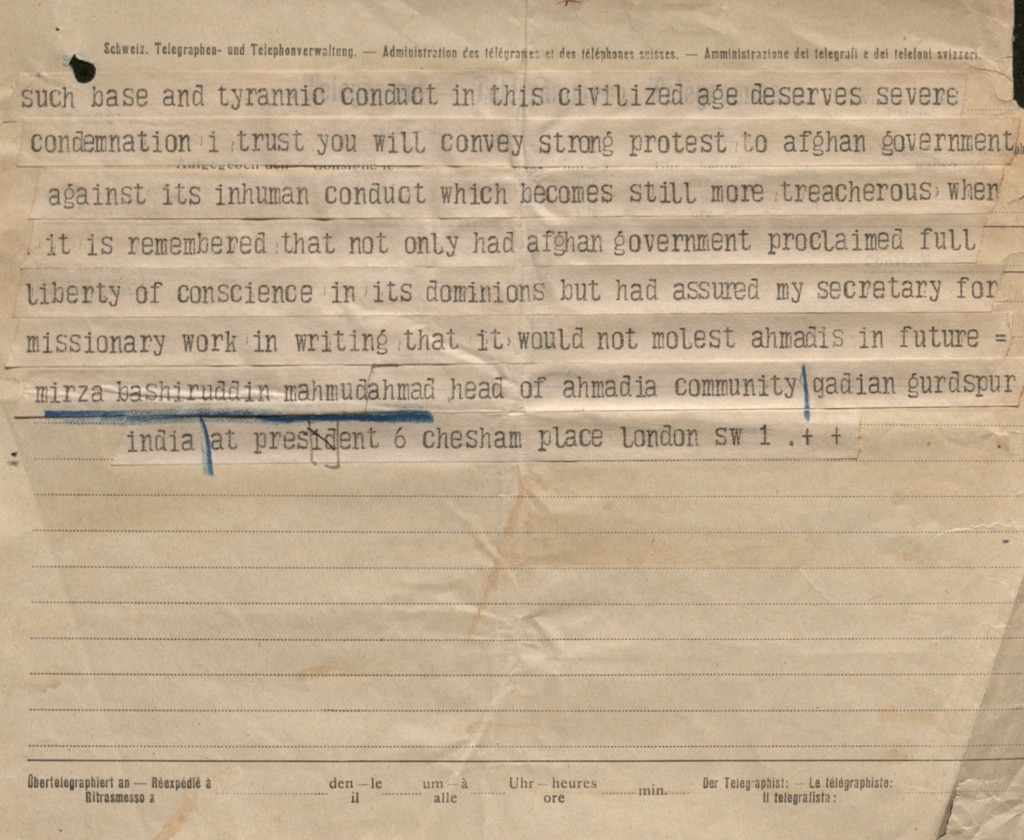

Fast-forward the tape of history and pause it at 1924: The same act of brutality was repeated with two other believers of Hazrat Ahmadas, again under direct orders of the Amir of Kabul.

India Office records have a file titled Afghanistan: Persecution of Ahmadiyya Sect (Political, 3607, 1924). It holds numerous cuttings from British mainstream newspapers that reported a protest meeting held at the Essex Hall in London. We present, as sample, a report published by The Times, London, on 4 September 1924. Headlined “Priest stoned to death” and “sacrifice for his faith”, the column-long story states:

“His Holiness the Khalifa-tul-Masih, head of the Ahmadia movement, who is in London, received news yesterday that Niamatullah Khan, the chief priest of the movement in Afghanistan, had been stoned to death by order of the Amir on Saturday […]

“His Holiness stated that the outrage was the culmination of a series of atrocious and barbarous acts directed by the Afghans against the Ahmadia movement owing to its opposition to the preaching of the Holy War.

“He added that he intended to appeal to the British Government and the League of Nations to protest against the action of the Amir.”

The Times, London, on 6 September 1924, published a detailed note on how the Amir of Kabul had ordered the execution by stoning of an Ahmadi as a punishment for apostasy, stating clearly:

“The execution by the Ameer’s orders of Maulvi Nimatulla Khan, who was stoned to death after months of torture, is regarded as significant of the seriousness of the position in Afghanistan”.

The British bureaucracy, in Simla and Whitehall both, could not ignore the protest meeting widely reported by the British press. The highlight was the resolution passed during the protest meeting that had been presided by Dr Walter Walsh and signed by not only Muslim dignitaries but by English intelligentsia as well. Among the English signatories were the likes of HG Wells, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Sir Francis Younghusband.

This resolution, sent to the prime minister of the United Kingdom and to the president of the League of Nations, called for stopping the growing religious extremism in Afghanistan in its tracks, before things got out of hand.

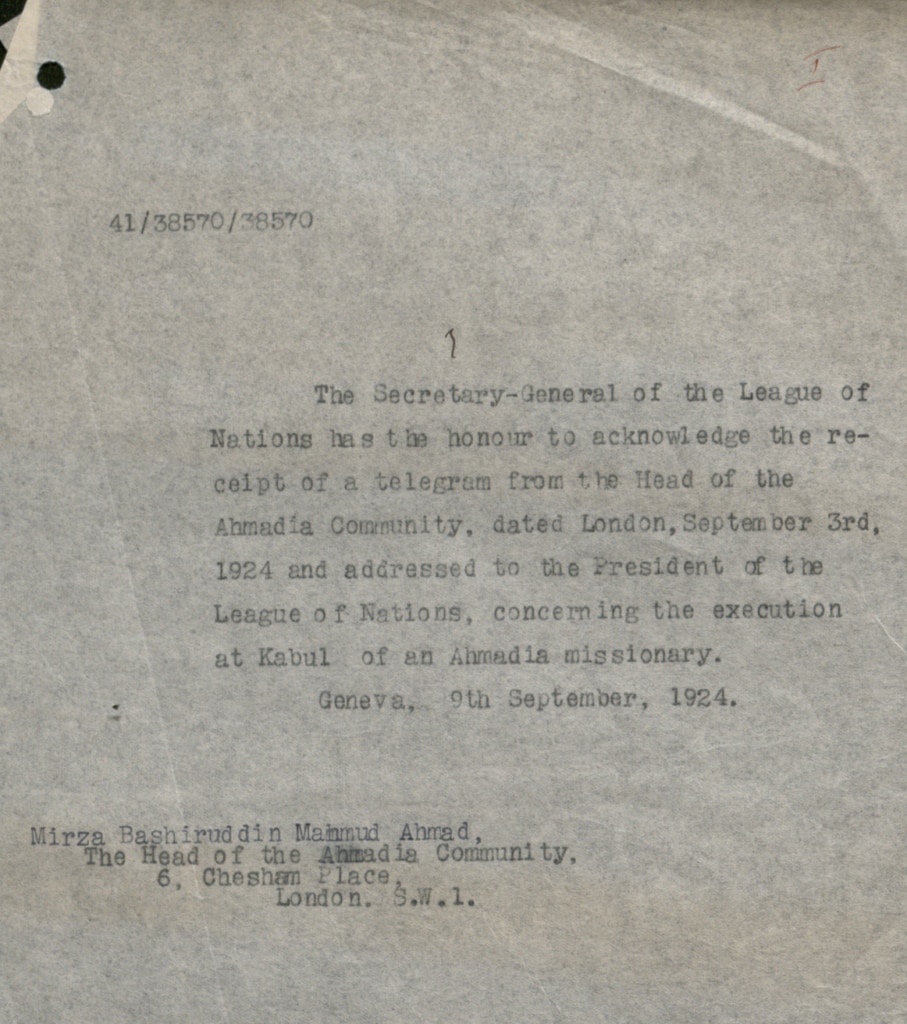

There is evidence that the president of the League of Nations received it – and thanked for it – but no further action can be found in the League of Nations records (now part of the UNO records in Geneva).

Whitehall and Westminster can be seen, through the aforementioned India Office records, grappling with the situation. The records reveal shocking facts.

Ministers from the Home and Foreign Offices are seen seeking advice from Scotland Yard as to whether they should honour the invitation and attend the protest meeting.

Titled An Extract from Report by New Scotland Yard, a report was sent back to the ministers by an Arthur Field. The report opens with the following words:

“Regarding a meeting called for Wednesday, 17th September, 1924, at 8.15 at Essex Hall, when ‘His Holiness the Khalifat ul Masih’ will speak at a meeting to protest against the Muslim populace stoning one of the Ahmadi schismatics to death, I unhesitatingly ask you not to attend.”

Letters are sent to and fro by ministers – their bureaucrats scribble notes in the margins – and then, finally, the Foreign and Political Department, India, writes back to LD Wakely (Secretary, Political Department, India Office, London), on 25 November 1924:

“The Government of India consider that it would be dangerous to make any representation, however informal, to the Afghan Government in the matter […]” (India Office Records, Political/Secret P4828, 1924)

While religious extremism in Afghanistan was in its formative phases, the British government was fully aware of it and also, possibly, of what it could grow into. The Amir of Kabul was a puppet with his strings tied to the British diplomats in India (proof of which will be provided in a separate article); presenting the best opportunity for the British to mould the extremist mindset that prevailed the Afghan Muslim scene.

Yet, the British government turned a blind eye to the menace in the making and let it grow into the monster that now embraces the whole world.

The Taliban insurgence is worrying. Their plans are extremely disturbing. But while the West looks at resolving the situation, they might want to take a quick jog down the annals of history. Clues to the solution could still be lying around covered in the dust of time.

MashaAllah, a great piece. I have learnt a lot of new information.

A very revealing article . Well researched with evidence . Clear and concise

Jazak Allah for all the hard work; very well documented timely statement of accounts of the historic events and glimpses of divine leadership/guidance.