The wisdom behind the physical acts of worship in Islam

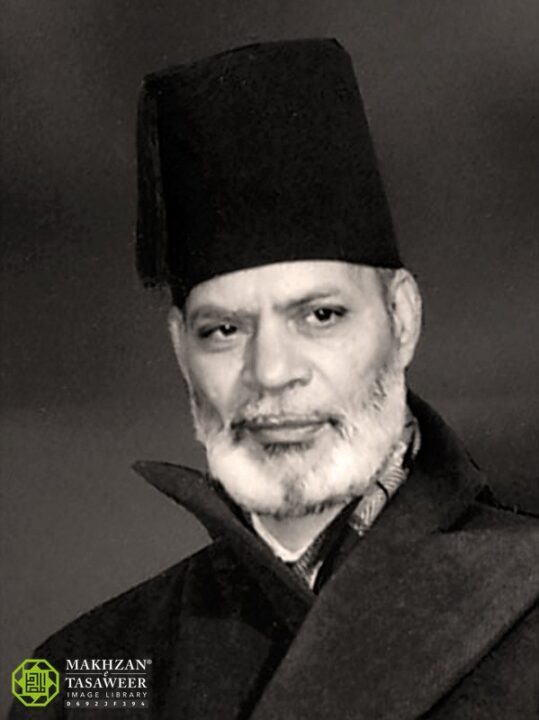

Hazrat Sir Chaudhry Muhammad Zafrulla Khanra (1893-1985)

Non-Moslem scholars as well as hostile critics of Islam assert that Islam pays very little attention to matters spiritual and that it lays undue stress on mere ceremonies. This they allege is a characteristic of all primitive forms of religion. At a time when human intellect was in its stage of infancy and no great philosophic truths had been discovered, man’s perception could not travel beyond outward appearances and the material things by which he was surrounded, and he, therefore, tried to win God’s pleasure by mere ceremonial and outward acts of worship. This is the reason why all old religions are full of rituals and ceremonies. In Islam too we find that great stress has been laid upon the performance of ceremonies.

[Development of worship in various religions]

[In addition to the profession of faith (shahadah), t]here are four pillars, as they are called, of Islam, viz., prayer (salat), fasts [siyam], pilgrimage to Mecca [Hajj], and the legal alms (zakat); all these are outward physical acts and so much stress is laid upon them that the omission of any of them renders a Muslim’s faith imperfect. What spiritual benefit, it may be asked, can be derived from certain prescribed movements at certain prescribed hours of the day, or from starving during certain seasons of the year, or from visiting certain spots on certain occasions, or from paying out a fixed sum within a prescribed period of time? Different people, it is alleged, living under a variety of circumstances and conditions can, if necessary, frame rules and regulations conducive to their respective material and spiritual progress. It is not necessary that all countries, ages and conditions should be subjected to one uniform code. Besides, all these prescribed acts are mere forms without any spiritual meaning in them, and although perhaps necessary in the case of a primitive people, can have no significance for the enlightened races of mankind. For instance, we see that different religions in the course of their evolution have completely discarded outward forms and have only retained their spiritual meaning. Take the case of Judaism. This great religion in its infancy was a mass of forms and ceremonies, but as it progressed the performance of mere formalities was less and less insisted upon. The study of the Bible reveals the fact that after Moses[as] each succeeding prophet laid less and less stress upon outward forms and directed people’s attention more and more towards spiritual matters, till in the time of Jesus Christ[as] the greatest stress was laid upon the doctrine that outward forms are but empty nothings and that purity of heart is the only object to be aimed at. Prayer and fasting belong to the spirit rather than to the body, and real success lies in purifying the mind and in establishing and maintaining the right relations with God and man.

The next great religion is Hinduism. Here too we find evolution on similar lines. In its primitive stage, this religion was enveloped in forms and ceremonies, but gradually it began to progress, till in the time of Buddha[as] it was proclaimed that outward ritual was nothing and that inner purity was the only true aim of religion.

All this is borne out by the doctrine of Evolution. If, on the other hand, we study the downfall of religions, we arrive at a parallel conclusion, viz., that with the decline of a religion outward forms begin to assert themselves more and more, till nothing is left but the mere outer shell of ritual. The decline of the Jewish, Hindu and Parsi faiths furnishes instances of this rule. The degeneration of Christianity in the Middle Ages further strengthens this conclusion. In the progress and decline of the Hindu religion we can very clearly trace these three stages, viz., the primitive stage, i.e., the stage of forms and ritual, the advanced stage, i.e., the stage of spiritual progress, and finally the stage of decadence, i.e., the stage of reversion to empty forms and ceremonies. These observations lead us inevitably to the conclusion that conformity to outward form is associated with the primitive stage of civilisation, and that with the advance of civilisation and progress outward conformity to forms begins of itself to decline, inasmuch as such conformity is required only of a people who possess a primitive intellect, and who are incapable of grasping abstract spiritual truths. Hence the stress which Islam lays upon formalities shows that this religion was suited only to the primitive condition of the Arabs at the time of its appearance and that it is totally unsuited to the needs and requirements of this age of civilisation and progress, wherein the purity of the soul is regarded as the only true aim of religion. The result of this is that even among the [Muslims] there has sprung up a class who do not view these “outward forms”, as they call them, with any respect.

[Views of a Muslim graduate of Aligarh]

Some years ago a [Muslim] graduate gave expression to these ideas in an article which he sent for publication to various papers. He pointed out that ablution (wuzu), prayers, fasts, the pilgrimage, etc. were suited only to the condition of the Arabs, and that they were mere symbols and no more. According to him the Holy Prophet (peace and blessings of God be upon him) prescribed these acts merely to point out to us the manner in which he desired us to conduct ourselves and that the form prescribed by Islam for these acts possessed no special virtue. As the Arabs of that time led very irregular and disorderly lives and had absolutely no idea of, or regard for, the value of time, the five daily prayers were instituted, in order to introduce among them notions of regularity and punctuality. Similarly, as they were not very cleanly in their habits, especially owing to the scarcity of water, regular ablutions and other ordinances concerning physical purity were enjoined on hygienic principles. In this enlightened 20th century, however, civilised people go regularly through their daily ablutions and baths, and they, therefore, do not stand in need of any religious ordinance concerning these matters. Again, all educated people are not only fully alive to the value of time, but their time is generally so usefully occupied and they have so many engagements to keep, that the five daily prayers are mere superfluities. If, however, prayer is considered absolutely essential, the opening and concluding graces at meals should suffice to reconcile man to his Maker.

At the time of the advent of Islam, oriental monarchs insisted upon their subjects prostrating themselves before them, so that prostration was considered as the symbol of absolute submission and humility. Therefore was a Muslim required to prostrate himself before God, the King of kings. The oriental dress offering no inconvenient hindrances to the performance of this feat and Oriental limbs being supple enough to go through such evolutions, prostration became the principal feature of Muslim prayers. Great difficulties and inconveniences, however, attend the performance of this gymnastic feat in modern society. Modern sovereigns no longer regard prostration as an essential part of the homage due to them, and fashionable trousers no longer admit of prostration being performed without disregard of their safety and a sacrifice of decency on the part of the wearer. Even if a pair of modern English trousers could stand the strain of half a dozen orthodox sajdas, they would certainly be distorted out of all shape and proportion and would become absolutely unfit to appear in decent society around the lower limbs of any self-respecting member thereof. In addition to the resistance offered by one’s trousers, there is the want of suppleness of limb which can only be acquired by the constant use of the carpet or the floor as a substitute for chairs. The stiffness of the joints born of chairs and sofas renders the sajda, therefore, a physical impossibility.

Similarly, there is no sense in starving for a fixed period during the year. To keep up the symbol of fasts, however, it is enough if during Ramazan one reduces the number of meals. Light refreshments should not be objected to during the period of the fast. The pilgrimage to Mecca could with advantage be replaced by compulsory attendance at the annual Sessions of the Educational Conference and the League. Donations to the Aligarh College, the Muhammadan University and other national institutions could take the place of zakat. This is how a Modern Muslim graduate interprets the “symbols”, as he calls them, prescribed by the Quran and the Holy Prophet[sa].

Although only one man has been bold enough to give open expression to such ideas, unfortunately, there are thousands of Muslims whose thoughts run in the same channel but whose fear of public opinion prevents them from making an open profession of them. It is clear, therefore, that this aspect of the question is not only dwelt upon by hostile critics but is also agitating the minds of many thoughtful Muslims themselves. Some of these latter have practically renounced all connection with, and all interest in, the purely religious side of the faith, and others, who still feel an affectionate regard for the faith of their forefathers, either through long association or through habit or as the result of a purely national sentiment, employ themselves in inventing excuses and expedients which would meet these and similar objections on the part of non-Muslims and yet retain a semblance of the Islamic practices ordained by the Quran and the Holy Prophet[sa]. Among this latter class may be counted the young man whose views I have explained above.

His view is that all these practices are mere “symbols” and that, keeping their object in view, we are at perfect liberty to devise rules of conduct and practice which should accord with the conditions and circumstances under which we are now living.

[Refutation of the above views]

The truth of the matter, however, is that neither the enemies nor these so-called advocates of Islam have really understood, or made any serious attempt at understanding, the spiritual meaning which is hidden in every ordinance or practice enjoined by Islam. The very same doctrines of evolution and decline from which they have drawn their conclusions offer a complete refutation of those conclusions. Not a single religion which has succeeded in reforming the morals or in elevating the spiritual condition of any section of mankind has ever been free from these external physical acts of worship. The different stages through which a religion passes and which have been instanced in support of the theory under discussion illustrate only the result of neglecting one aspect of religion and giving undue prominence and attaching undue importance to the other. Where degeneration has resulted from too great subservience to forms, the reason has not been the mere observance of forms and their retention as part of the practice of the faith, but their acceptance as an end in themselves and the complete neglect of the spiritual aspect of religion, on the other hand, it has not been found possible to dispense completely with external acts even during periods of the highest spiritual progress.

Besides, there is a vast difference between the elementary teachings of Islam and those of other religions. The study of the Zend-Avesta, the Vedas, or the Bible reveals such minute and detailed regulations concerning the smallest affairs of life, that a [Muslim], being unaccustomed to such details, begins to wonder how fettered an existence the followers of those books must have led. For instance, the Book of Exodus, chapters 25 to 31, contains such detailed instructions concerning the building of the temple, the kinds of woods to be employed in different parts, the quality, colour and texture of the cloths and tapestries, the adornment of the altar, the ark, the mercy seat, the tables, the candlesticks, the curtains, the boards and bars, the garments of the priests, the holy garments and ornaments for Aaron and his sons and numerous other matters of the like nature, that one is absolutely bewildered, and marvels what extraordinary memories Moses[as] and his followers must have possessed to remember and carry out to the letter all these commands. Similarly, there are instructions about the proper performance and offering of the different kinds of sacrifices. The Hindu religion also contains a confusing wealth of ordinances concerning caste, purification, the different kinds and modes of worship and kindred subjects. The Zend-Avesta prescribes rules even for the preservation of water and the tending of the Holy Fire. In short, the visible forms and external acts prescribed by Islam are so few and so definite that an average [Muslim] accustomed to the regular performance of all the duties laid down by his faith would begin to find life too heavy a burden if asked to conform to all the rules set down by any of the books mentioned above.

It is quite wrong to say that Islam lays undue stress on mere forms. No doubt, Islam too has retained visible forms as parts of its practice, but only on occasions when, and to an extent to which, their observance leads to some physical or spiritual benefit. For instance, in salat, fasts, pilgrimage and the legal alms, visible forms have been adopted only so far as they are conducive to spiritual progress or the good of humanity at large.

[Salat: the benefits of wuzu (ablution)]

Let us first take salat. In order to complete his salat, a Muslim must perform the wuzu (ablutions) and then say his prayers in certain defined attitudes. Now, wuzu is a[n act of the] purification of certain external organs, viz., the mouth, the nose, the face, the head, the arms and hands and the feet. No doubt, there are many Muslims who habitually live in a state of irreproachable cleanliness, and it might be urged, that whatever the necessity or the benefit of wuzu in the case of those whose habits are not as cleanly as one would desire, it is clearly a superfluity in the case of those to whose purification it can add nothing. But apart from the fact that Islam contains ordinances alike for the rich and for the poor, for the tidy and for the untidy, the promotion of physical cleanliness is not the only object of wuzu, so that the tidiest Muslim can derive as much spiritual benefit from it as the most untidy. The washing of all those organs which lead a man towards sin indicates that prior to presenting himself before God the worshipper must wash off all immoral stains and must make himself as clean morally as the wuzu renders him physically. All sins originate with the hands, feet, eyes, nose and the mouth, and the ordinance enjoining a thorough cleansing of these organs requires symbolically, as it were, absolute moral purity on the part of the worshipper. As in wuzu, he removes every impurity from these limbs, so must he purify them by restraining them from all sinful acts.

Again, it is an established fact that our thoughts are constantly flowing out through our hands, feet, noses, mouths, etc., thus causing a constant disturbance. This fact has been illustrated by a French Scientist in a very amusing and instructive manner. He has invented an instrument, called the planchette, which may be roughly described as a slate on a wheel with a pencil attached to it; and this instrument can, by a very simple process, record the thoughts of the operator. One has simply to place the tips of one’s fingers very lightly on the surface of the slate to enable it to record the thought which is uppermost in one’s mind. Now, this constant flow of thoughts can only be checked by wetting the limbs with water, cold water proving a most effective remedy. In moments of excitement and disturbance of the mind, cold water ablutions restore one to absolute tranquillity and bring about that state of calmness and repose without which man shrinks from venturing into the presence of his Maker. The Holy Prophet (peace and blessings of God be upon him) has also recommended the use of cold water for ablutions.

These are only a few of the benefits to be derived from wuzu, but they are enough to prove that it is not a mere empty form. The five daily ablutions enjoined by Islam not only promote physical cleanliness, but the mental repose induced by them enables a man to go through his daily task patiently, cheerfully and without irritation. The hygienic benefits of wuzu, however, are not negligible either. It can, with confidence, be asserted that a Muslim who is regular in his five daily prayers exhibits a far higher standard of personal cleanliness than the majority of Europeans in similar walks of life. Indeed the introduction of compulsory wuzu among certain sections of the population of Europe would result in their leading cleaner, purer and happier lives than they are at present doing.

[Salat: outward expressions affect the inner self]

Similarly, the attitudes adopted in Muslim prayers appear at first sight to be mere formalities with no spiritual meaning whatever, but in reality, they constitute a regular course of spiritual training, and a little reflection would make this apparent. The human soul is encased in the body and the latter serves it as a vessel or as a shell, and the condition of the vessel affects its contents as the condition of the shell affects the kernel. A dirty vessel is sure, sooner or later, to contaminate its contents, and a crooked one is bound to impart to its contents its own crooked shape. For instance, we find that the amount of intellect possessed by an individual depends upon the shape, dimensions and structure of his brain, and the development and decline of the intellect are subject to the development of the physical characteristics of the brain. If by some accident or some scientific operation the shape of a man’s brain could be altered, his intellect would be affected at once, notwithstanding the fact that no diminution or increase has taken place in the quantity of the substances of which the brain is composed. The assumption of a particular facial expression or a particular attitude produces a corresponding change in our powers, manners or moods. For instance, the mildest of men could, by assuming a stern expression of countenance, acquire a corresponding sternness of character. A high functionary in one of the American States, placed in a position of great authority which required the exercise of strict control and discipline, was pronounced absolutely unfit to perform his duties, inasmuch as he totally lacked the will and resolution to carry out disciplinary measures. He could never bring himself to administrate the slightest reproof or punishment. At last, he was told that unless he could infuse a little more firmness and resolution into his character he would no longer be allowed to retain his post. He then went to consult a character specialist and was told that he must put on an expression of sternness, keep his teeth clenched and generally assume a severe manner. He relates that after going through this course of assumed sternness for a few months he began to find that he was growing really severe and that gradually he practically lost all feelings of compassion and forgiveness! This is a very convincing illustration of the influence which the mere assumption of an attitude or an expression exercises on one’s character.

Physiognomists and phrenologists are able to read a man’s thoughts and character from a study of his features and the shape of his head, and these sciences have been reduced to definite principles. These sciences demonstrate that there is a strong relationship between a man’s outward form and his character and that they both react to each other. A moral or spiritual charge in a man’s character produces a corresponding change in his features or in the expression of his countenance and vice versá. By the artificial development of certain parts of the head or face of a man, it has been found possible to develop certain moral characteristics in him, so that it cannot be denied that every alteration in the physical condition of a man has its corresponding effect on his moral or spiritual nature. Weeping, even if artificial, saddens the heart, while even an artificial laugh is sure to dispel the fogs of melancholy. Similarly, certain foods develop certain qualities in those who make use of them. On the same principle, certain attitudes and postures are not only symbolical but induce certain states of mind. All the attitudes and postures prescribed in the Salat are productive of meekness and humility, and not one of them has been enjoined as a mere formality. They are all natural expressions of respect and homage. Similarly, jama‘at (congregation) is a symbol of union. When the Muslims stand in rows to offer their prayers, they in a manner express by their attitude that in all spiritual trials and contests they would stand steadfastly by each other, and help each other in carrying out the commands of God.

Besides, it must be remembered that no kernel can exist independently of its shell, and a shell is to be valued only for the sake of the substance which it contains. Those who neglect the shell altogether, in the end, lose the substance also. Those peoples who have completely discarded outward religious forms have also gradually lost the spiritual reality. In the case of the greater portion of mankind the result of the neglect of outward forms would be that everybody who finds the ordinances of his religion a little irksome or inconvenient would allege that he can acquire the substance without the shell and that therefore conformity to those ordinances is not obligatory on him. Hence, this freedom instead of helping spiritual progress would lead millions of men to spiritual death, as is apparent from the plight of those who in answer to these objections allege that purity of heart is the only object worthy of being striven for and that external acts have no virtue in themselves. Such people lose both the shell and the substance; they do not retain external conformity and fail to attain inner purity. Their hearts become foreign to the fear and the love of God, whereas if the substance could be acquired without the shell, it should have followed that their hearts should not for a moment have lost sight of God. By neglecting external acts of worship, they become incapable of rendering the true homage of the heart to their Maker. Conformity to salat would at least have directed their attention to God five times a day.

No doubt the real object is the substance and not the shell, but can any kernel exist without the shell? From a study of the laws governing external nature we can discover the laws governing our spiritual development. In external nature, we find that the outer skin or shell is necessary for the development of the substance or the kernel. Would it be wise to do away with the skin or the shell of a fruit because we only want the sweet substance of the fruit and not its outer covering? It is a universal rule that fine and delicate substances are protected by rough coverings, and just as the soul stands in need of the protection afforded by the body, our spiritual devotions stand in need of physical expressions. The mistake lies not in adopting outward physical symbols of worship but in regarding these outward expressions as the only object of worship, and this is strongly condemned by Islam. The object of salat is thus expressed in the Quran:

اِنَّ الصَّلٰوةَ تَنۡهٰي عَنِ الۡفَحۡشَآءِ وَالۡمُنۡكَرِ

“Salat keeps one away from unseemly and undesirable acts.” [Surah al-’Ankabut, Ch.29: V.46]

Elsewhere the Quran strongly condemns those who perform acts of worship for mere show and outward conformity. The Holy Prophet (on whom be peace and the blessings of God) has said that prayers unattended by the devotion of the heart are useless and that real prayer is that in which the heart finds itself in the presence of its Maker.

[Siyam: fasting]

Next, there are the fasts. Here too it is supposed by some people that the act of worship consists in merely abstaining from food and drink during certain prescribed periods of the year, whereas fasts are not merely feats of abstention but lead to great spiritual benefits. It is an admitted truth that the connection of the soul with the body inclines the former towards material objects and pleasures. This is the reason why the spiritual perception of those whose principal concern is the care of the body becomes dulled. We find that people engaged in intellectual pursuits devote comparatively little attention to eating and drinking and the mere physical pleasures of the body. Very often their food and dress are matters of indifference to them, beyond the fact that the former should be healthy and the latter clean. Even in these days of material comfort and luxury, we find that the intellectual portion of every community bestows comparatively little time and attention upon mere physical comforts. This shows that until the soul is to some extent freed from the trammels of the body it cannot soar very high in the intellectual and spiritual realms.

[Siyam: fasting in other religions]

A study of the lives of men who have attained spiritual eminence in any age or religion shows that all of them have kept fasts during some part of their lives. Almost all spiritual leaders and founders of religions have enjoined their followers to keep fasts. Out of the thousands of religions which have flourished or are flourishing in this world, there are only two, viz., the Parsee religion and the religion of Confucius[as] about which it has been asserted that they do not enjoin fasting on their followers. As regards the Parsi religion, however, modern investigation has established that fasts were enjoined by that religion, although the keeping of them has now fallen into disuse through neglect of the ordinances of that religion. One of the prayers in use among the followers of that religion contained a reference to fasting. Thus every religion, ancient or modern with the solitary exception of the religion of Confucius[as], is found to have contained ordinances concerning fasts. It is possible that further investigation may yet disclose the fact that Confucianism is no exception to this rule. However, this single exception, in the face of the united testimony of all the other religions of the world, dead or living, is not sufficient to refute the proposition that at all times and among all religions the keeping of fasts has been considered essential for spiritual progress, or at any rate, that fasting helps spiritual progress. In the present day, the followers of Christianity, especially those belonging to the Protestant Churches, are the greatest objectors to outward acts of worship, yet even here we find that Jesus Christ enjoined fasts on his followers and that the disciples kept fasts. Among all Christian communities the great fast of Lent is still recognised and to a certain extent observed. This shows that fasting has not been enjoined as a mere ceremony but has a deep spiritual meaning.

For instance the Holy Quran says:

كُتِبَ عَلَيۡكُمُ الصِّيَامُ كَمَا كُتِبَ عَلَي الَّذِيۡنَ مِنۡ قَبۡلِكُمۡ لَعَلَّكُمۡ تَتَّقُوۡنَ

(Fasts have been enjoined upon you, just as they were enjoined on those who were before you, in order that you may attain to purity of heart.) [Surah al-Baqarah, Ch.2: V.184)]

In this verse, the Holy Quran has dealt with both aspects of the matter. It says that fasts have been “enjoined” upon you, thereby declaring that the mere keeping of a fast simply because God has enjoined fasting is an act of worship which pleases God. This would amply satisfy those who wish to perform an act of worship simply because it would please God and not because they would thereby secure some direct spiritual benefit or reward. This, however, the Holy Book says, is not an obligation imposed upon you alone. It was considered equally necessary for the spiritual progress of former nations and was also imposed upon them. It is not an empty form or ceremonial. The real object of the injunction is that you may attain to purity of heart. Thus the Holy Book explains that by means of fasts a man gains strength to avoid all manners of sins and evil-doing and attains nearness to God. The reason for this is that fasting loosens the bonds which bind the soul to the body, and the former being thus set free is enabled to soar higher and higher into spiritual realms. On the other hand, there is no doubt, that while the soul seeks separation from the body for the sake of its intellectual and spiritual development, it seeks union with the body in order to attain perfection in deeds. This double requirement demonstrates the need for fasting at some seasons and for administering to the needs of the body at others. In Islam, therefore, while on the one hand, fasting has been enjoined as a religious obligation during Ramazan, continuous fasting during other seasons has been altogether prohibited, so that this arrangement ensures opportunities for development in every direction. There is neither too much ease nor too much asceticism in Islam. It aims at creating neither hermits nor epicures. Its object is to encourage the symmetrical development of every faculty, and not the abnormal development of certain faculties at the expense of others.

Siyam: benefits of fasting in Islam

Apart from the principal object of attaining taqwa (righteousness) fasting leads to many other beneficial results. For instance, it is a great test of endurance. For a poor man to whom one full meal a day is a luxury it may be comparatively easy to abstain from all food and drink for sixteen or seventeen hours, but for a rich man who is accustomed to his four meals a day at regular hours the limit of endurance is reached when he is asked to deny himself food and drink from earliest dawn till after sunset on a hot summer’s day, and this not only on a single occasion but during a whole long month. Imagine a wealthy man accustomed to all sorts of delicacies imposing upon himself such a course of stern self-discipline during a whole month and relaxing it neither in thought nor in deed! Thus, Ramazan keeps alive habits of patience, abstinence and endurance even among the richest Muslims. It also awakens the wealthy to a realisation of their duties towards the poor, especially during times of hardship and famine. A man who has never missed a single meal in his life is not likely to be aroused to much sympathy by the knowledge that to thousands of his fellow beings one full meal a day is a luxury. The pangs of thirst and hunger have no meaning for him. It is a form of ill to which he himself has never been subject and for which, therefore, he is not likely to afford much sympathy. A man, on the other hand, who fasts during one month out of every twelve is not likely to treat the solid facts of hunger and thirst with indifference. The knowledge that there are fellow beings of his to whom a loaf of bread might mean life itself will keep him restless till he has done all that in him lies to relieve the distress around him. The reality experienced by him will prevent him from dealing with such matters lightly.

Similarly, there are many other benefits which result from an observance of this injunction, but they are all minor or secondary ones and it must be clearly understood that the chief object to be attained by fasting, as already stated, is taqwa (righteousness). The Holy Prophet (may peace and the blessings of God be upon him) has said that the pleasure of God cannot be won by mere abstention from food and drink and that so long as a man’s fast does not keep him away from evil, it is not a fast but mere starvation. This shows that the true aim and object of fasting is to gain strength to avoid evil and to purify the soul, and the man who observes the form and forgets the substance gets no credit for his starvation.

(Transcribed by Al Hakam from the original, published in The Review of Religions, Vol. XVII, October 1918, No. 10, pp. 341-357)