Ata-ul-Haye Nasir, Ahmadiyya Archive & Research Centre

The “non-Muslimness” of Ahmadi Muslims is often talked about among various sections of the Muslim community and they are alleged to be the enemies of Islam.

These sentiments against Ahmadi Muslims are not new. The Founder of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, Hazrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmadas of Qadian, also faced opposition from his co-religionists and was labelled a kafir (disbeliever) and an enemy of Islam, among other labels.

Looking at the early half of the 20th century, we find that various sections of the Muslim community in British India were demanding the exclusion of Ahmadis from the pale of Islam.

This anti-Ahmadiyya rhetoric intensified after the Partition of British India, so much so that in September 1974,1 the Parliament of Pakistan declared Ahmadis as non-Muslims. However, this was not the first time the Ahmadiyya faith had come under discussion at a legislative body.

We find multiple instances where certain questions were posed, or an attempt was made to do so, about the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community’s beliefs and its connection with Islam at the legislative assemblies of British India. The official records of the British Indian Government’s Home Department provide significant information about these events, to which we will turn later in this article.

1925: Defence of Islam and ‘non-Muslimness’

Let’s first glance at the turbulent 1920s in British India. It was a time when several religious and political conflicts had surfaced.

The anti-Islam rhetoric was reaching new heights and the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat was defending the honour of Islam. As a result, it was facing continuous assaults from the opponents of Islam and also severe opposition from its co-religionists.

Focusing on the events of exactly 100 years ago, we find very interesting incidents – highlighting how the Ahmadi Muslims were defending Islam and showing concern for the Muslim rights and interests, while still being considered non-Muslims. Particularly, the new wave of Shuddhi Movement was being emphatically tackled by the Ahmadi missionaries.2

i) Nur-i-Afshan and Anjuman Islah-ul-Muslimeen

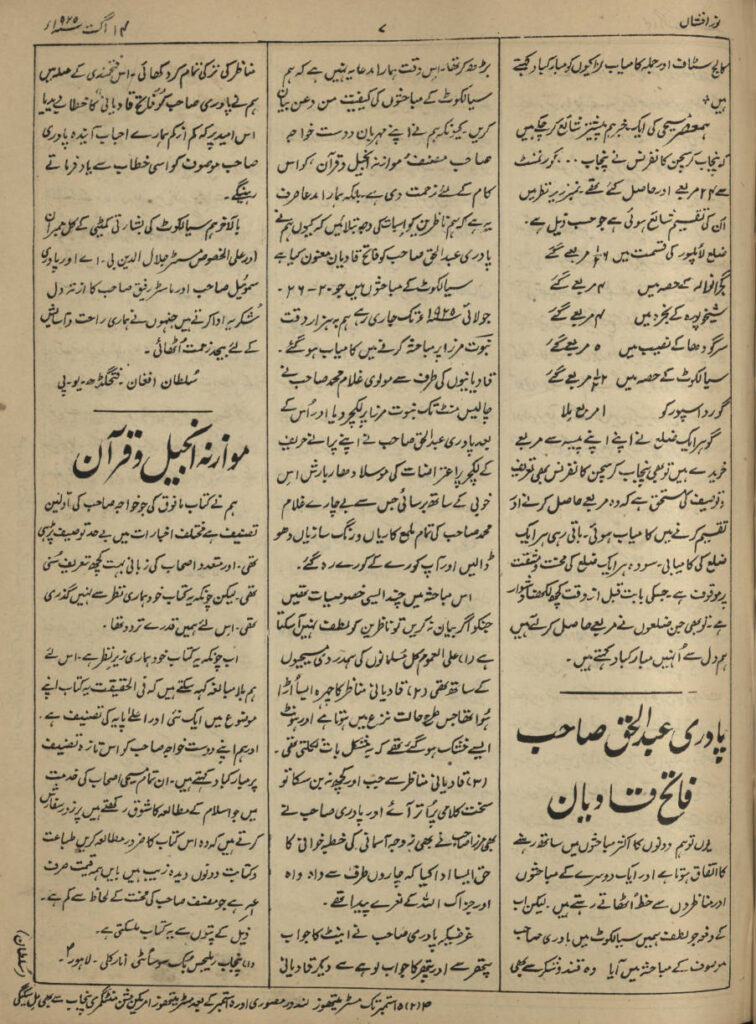

The second half of 1925 saw a series of debates in Punjab, between the Ahmadi Muslims and the Christian missionaries.3

The Nur-i-Afshan of Ludhiana – a leading Christian newspaper of the time – published multiple articles in August and September 1925, mentioning the Christian missionaries’ debates with the representatives of Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya. These articles were declaring their victory over Islam and even mentioned Rev Abdul Haq as the “Faatih-e-Qadian” (literally, Conqueror of Qadian).4

Interestingly, an article of Nur-i-Afshan reproduced a letter, dated 1 August 1925, from the Secretary of Anjuman Islah-ul-Muslimeen Delhi – Syed Mumtaz Hashmi – who expressed his views about these debates between the Ahmadi Muslims and Christians. He asserted that, God forbid, Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya was a part of Christianity, not of Islam. He continued by making the following statement:

“Whether the Mirzais stood victorious or the Christians, it has nothing to do with the Muslims. This is because – my respected friends should bear in mind – the success of any non-Muslim power over any Mirzai clerk or missionaries is not hujjat for the Muslims. The majority of the Muslim community unanimously considers the Jamaat-e-Qadian as outside of the pale of Islam.”5

How ironic that the very community which was defending the honour of Islam and its Holy Foundersa amidst unprecedented attacks from the opponents, since its inception, was being declared non-Muslim.

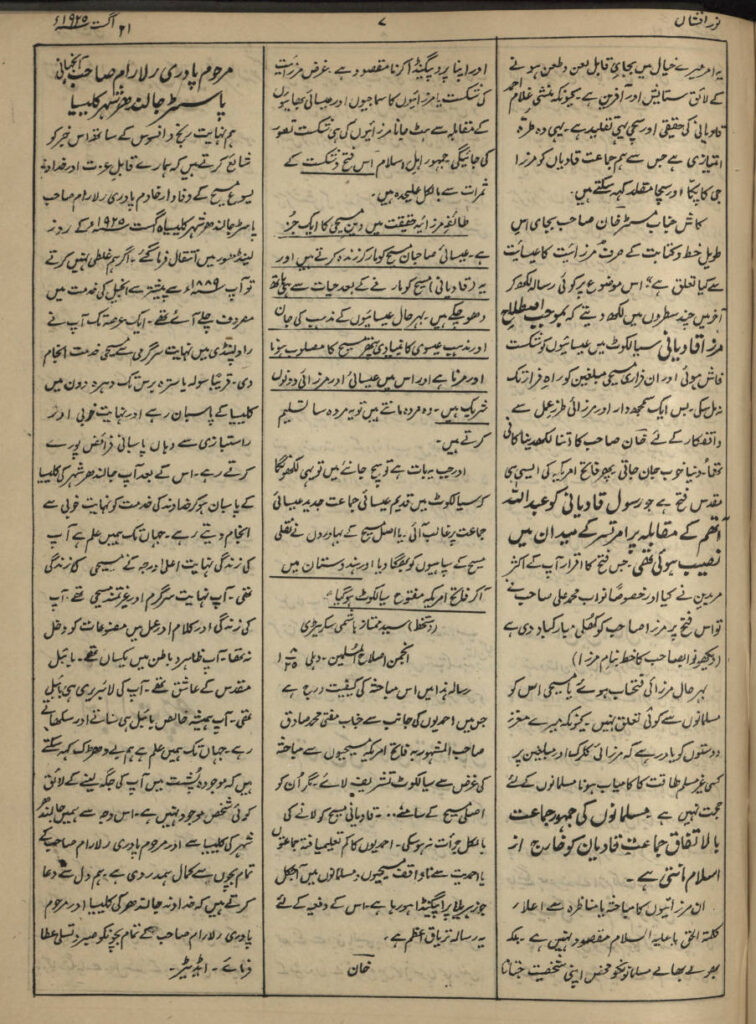

ii) Maulvi Sanaullah Amritsari’s comments

The Ahmadi Muslims were defending Islam amidst the Christian attacks in such an emphatic manner that even the staunch opponents of the Jamaat had to accept it.

For instance, Maulvi Sanaullah of Amritsar – an opponent of Ahmadiyyat – was also compelled to acknowledge in his newspaper, Ahl-i-Hadith, that the Ahmadi missionaries stood victorious against the Christian missionaries.6

However, he asserted that since Ahmadis conduct debates with the Christians and Aryas in defence of Islamic issues (masa‘il), they achieve victory only because of the might of Islam, not due to Ahmadiyyat’s truthfulness. He claimed that Ahmadis were wrong in presenting their victory over Christians as a proof of the truthfulness of the Promised Messiah’sas claims and revelations.7

iii) Concern for the Siamese Muslims

Speaking about the year 1925, another example of Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya’s loyalty to Islam is found in regard to the issue of Siamese Muslims. The Indian newspapers started highlighting the rumour about forcible conversion of Siamese Muslims to Buddhism. When these rumours emerged, Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya raised its voice for Siamese Muslims and contacted the British officials in Siam for more information on this matter.

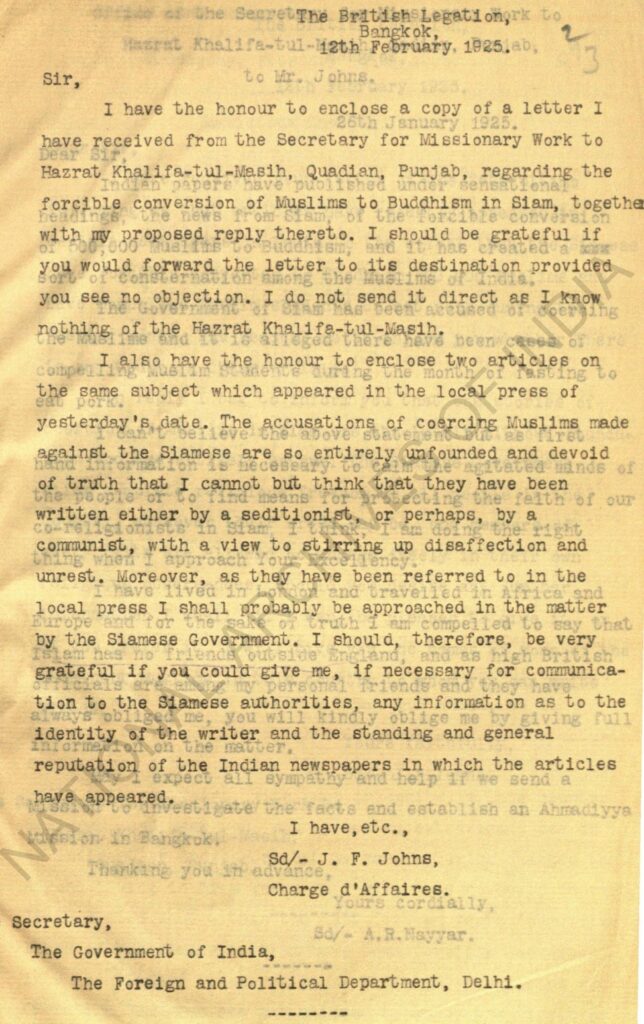

A letter dated 12 February 1925, from J F Johns – British Charge d’Affaires in Bangkok – to the Foreign and Political Department of the Indian Government, mentioned a correspondence received from Qadian. He wrote:

“I have the honour to enclose a copy of a letter I have received from the Secretary for Missionary Work to Hazrat Khalifa-tul-Masih, Quadian, Punjab, regarding the forcible conversion of Muslims to Buddhism in Siam.”8

In response to this letter from Hazrat Maulvi Abdur Rahim Nayyarra, the British Charge d’Affaires wrote that “the stories of coercion of Muslims in Siam are absolutely without foundation and are entirely untrue.”9

Nonetheless, this episode was another example showcasing the care and concern shown by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat for the Muslim interests.

1930s: Ahrar and the legislative assemblies

Amidst the religious or political problems faced by the Indian Muslims, Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya was always ready to provide solutions and the good-natured Muslim leaders would even invite the Ahmadiyya Khalifa and prominent Ahmadis to various conferences.

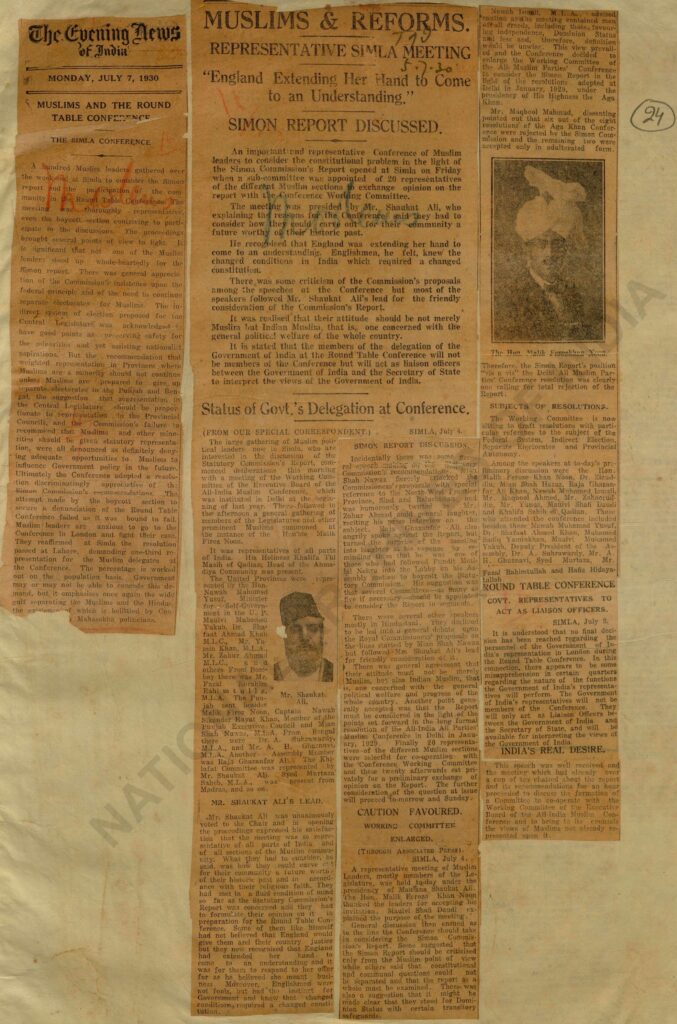

For instance, in April 1912, Allama Shibli Nomani invited Hazrat Sahibzada Mirza Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmadra to attend the Annual Conference of the Nadwat-ul-Ulama,10 and then in 1930 – according to a report by The Times of India – Ahmadiyya Khalifa delivered a speech at the All-India Muslim Conference in Simla.11

The services of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat for the oppressed Kashmiri Muslims are a shining example of its loyalty to Islam. However, this episode – according to The Civil and Military Gazette – “made Ahrars green with jealousy.”12 Thereafter, they initiated the anti-Ahmadiyya agitation and vigorously demanded the exclusion of Ahmadis from the pale of Islam.

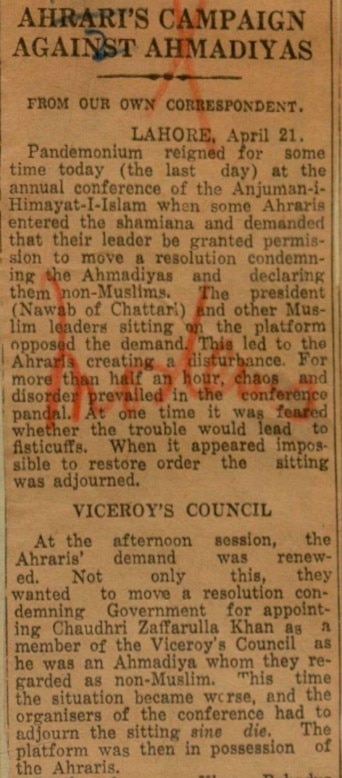

For instance, during the 1935 Annual Conference of the Anjuman-i-Himayat-i-Islam, some Ahraris entered the Jalsa Gah and “demanded that their leader be granted permission to move a resolution condemning the Ahmadiyas and declaring them non-Muslims.” However, the president and other Muslim leaders sitting on the platform opposed the demand.13

Further, during an Ahrar Conference in Lyallpur, a resolution was passed demanding the showing of Ahmadis “as a section separate from Muslims.”14

Moreover, the Ahrari leaders created commotion upon Sir Zafrulla Khan’sra appointment as a member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council.15 Multiple letters “were sent to the Viceroy, stating that ‘You have appointed a “non-Muslim” to fill the vacancy of a Muslim. Remove Zafrulla Khan and appoint any other Muslim in his place.’”16

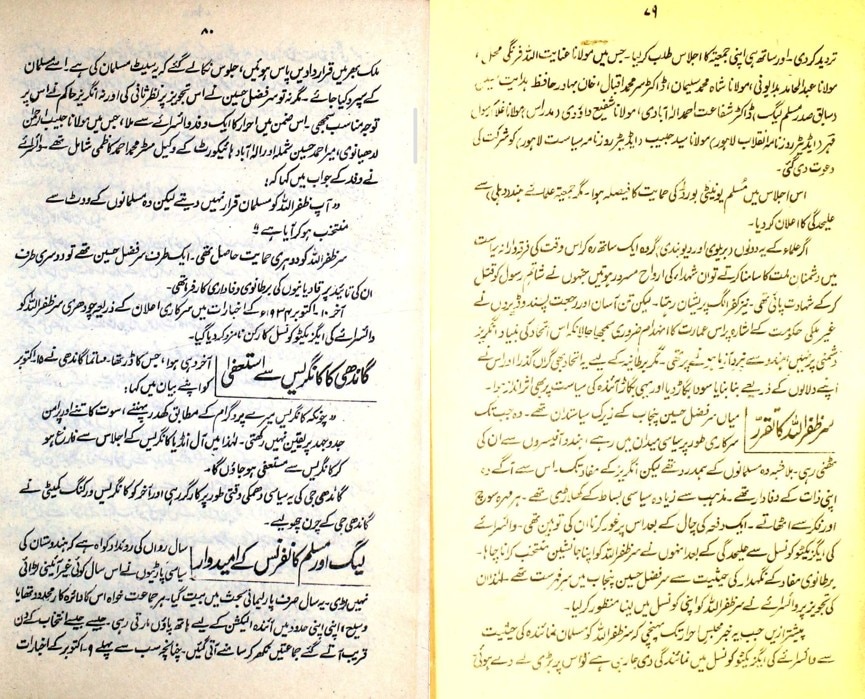

Janbaz Mirza, the official historian of Ahrar, has stated that “when the news came to the Majlis-e-Ahrar that Sir Zafrulla was being granted representation in the Viceroy’s Executive Council as a Muslim representative, it caused great concern. Resolutions were passed all over the country, [and] protests were carried out saying that this seat is reserved for a Muslim and should be given to a Muslim.”17

He also mentioned that a deputation of Ahrar met the Viceroy of India and expressed their concerns, however, the Viceroy responded:

“You do not consider Zafrulla Khan to be a Muslim; however, he has been elected through the Muslim votes.”18

In short, the 1930s was an era when the urge for declaring Ahmadis as non-Muslims was at its peak. So much so that the beliefs of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community were brought under discussion at the Legislative Assembly of British India.

On one occasion, when the Ahmadiyya faith was questioned at the Legislative Assembly of British India, some members of the House expressed that the legislative body ought not indulge in such debates, even suggesting that it was a waste of time. This article will particularly narrate details of this episode and, in general, of some other instances where the Ahmadiyya faith was questioned at the legislative assemblies of British India.

1932: Questions at the Central Legislative Assembly

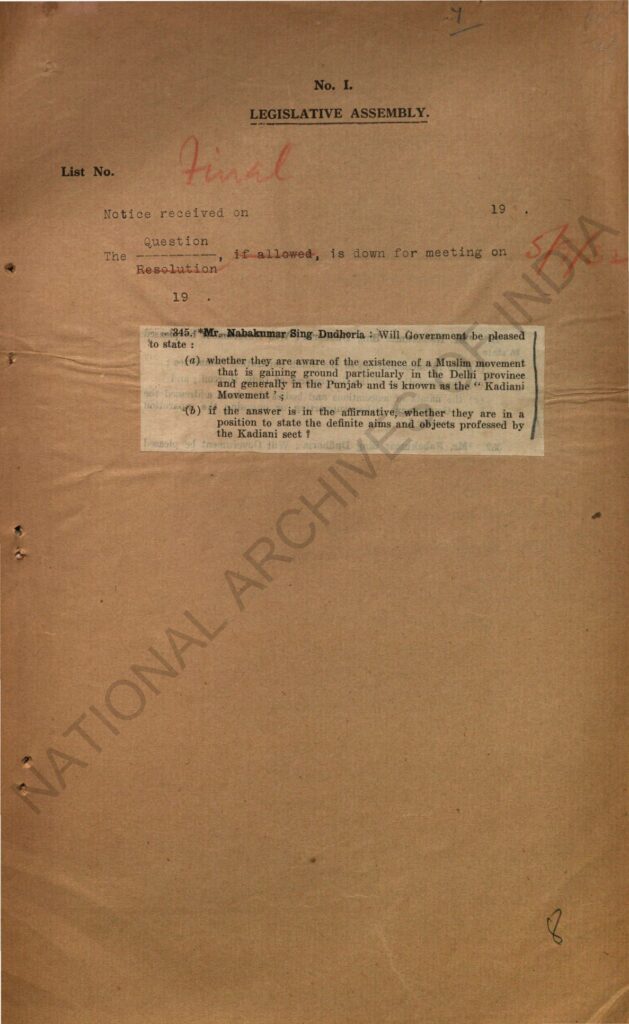

In August 1932, a member of the Central Legislative Assembly of British India – Nabakumar Sing Dudhoria – proposed some questions to be asked about the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community.

i) The proposed questions

The proposed questions, as initially formulated by the member of the Assembly, were as follows:

“Will Government be pleased to state:

“(a) whether they are aware of the existence of a Muslim movement that is gaining ground particularly in the Delhi province and Kashmir and generally in the Punjab and is known as the ‘Kadiani Movement’;

“(b) if the answer is in the affirmative, the definite aims and objects professed by the Kadiani sect; and

“(c) whether the sect is purely religious or politico-religious?”19

ii) Correspondence between the Home Department and the D.I.B

Following these questions, a series of correspondence got initiated between the government officials at the Home Department (H.D.), the Foreign and Political Department (F & P Dept.) and the Director Intelligence Bureau (D.I.B). This correspondence also included letters to-and-fro Hazrat Sir Zafrulla Khanra.

A query from the Home Department to the Director Intelligence Bureau stated that the Foreign and Political Department “have asked us whether we are dealing with this question. We may agree to do so.”

It further mentioned that “the Kadianis or Qadianis are, it is understood, identical with the Ahmadiyas, our information about whom is very scanty,” and perhaps the “D.I.B. may have more information than we have. We would be thankful for a reply.”20

In response to the query from the Home Department, the D.I.B suggested a reply to the proposed questions.

The Director also wrote that “the Qadiani religion cannot, in my opinion, be described as a Muslim movement; it is a religion established over 40 years. Its history up to 1928 is contained in the Supplement to the Punjab Police Secret Abstract of Intelligence dated June 2, 1928.”

He further stated, “I understand that the Hon’ble Member for E.H. & Land Department is himself a Khalifa [sic., follower] of His Holiness Mirza Bashiruddin Mahmud. Possibly, H.D. may like to consult him as to the reply. Personally I should doubt the question receiving the approval of the Hon’ble the President of the Assembly.”21

Here, the Director was pointing toward Hazrat Sir Zafrulla Khanra as he was serving in the Education, Health and Lands Department at the time.

iii) Correspondence between HG Haig and Sir Zafrulla Khanra

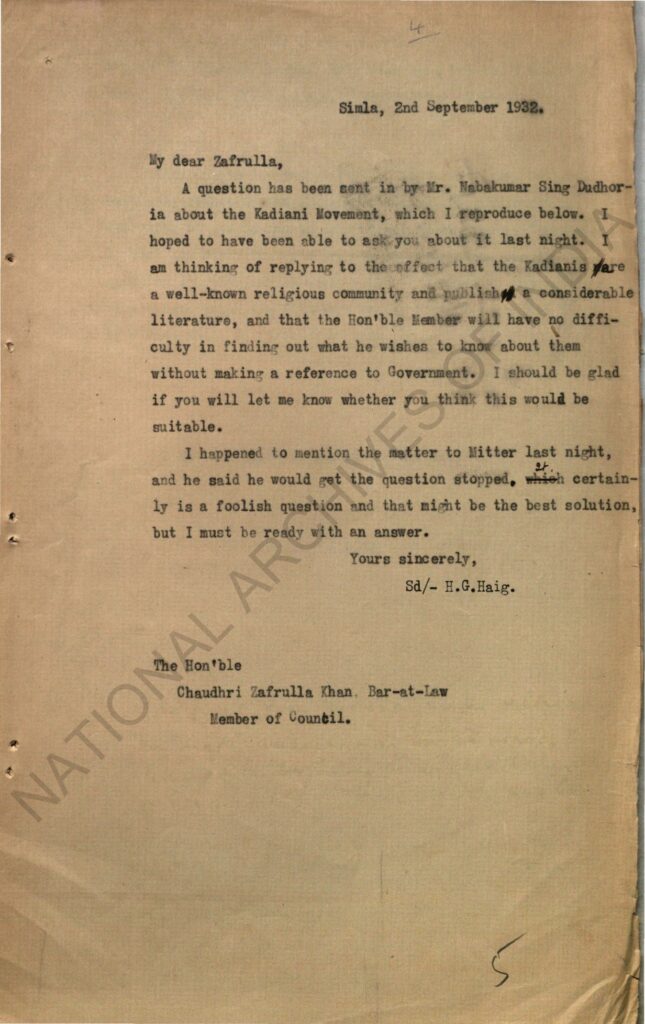

This was followed by a letter, dated 2 September 1932, to Hazrat Sir Zafrulla Khanra from Harry Graham Haig (1881-1956) – Home Member of Executive Council of Governor-General, India – which ran as follows:

“A question has been sent in by Mr. Nabakumar Sing Dudhoria about the Kadiani Movement, which I reproduce below. I hoped to have been able to ask you about it last night. I am thinking of replying to the effect that the Kadianis are a well-known religious community and publish a considerable literature, and that the Hon’ble Member will have no difficulty in finding out what he wishes to know about them without making a reference to [the] Government. I should be glad if you will let me know whether you think this would be suitable.

“I happened to mention the matter to Mitter last night, and he said he would get the question stopped. It certainly is a foolish question and that might be the best solution, but I must be ready with an answer.”22

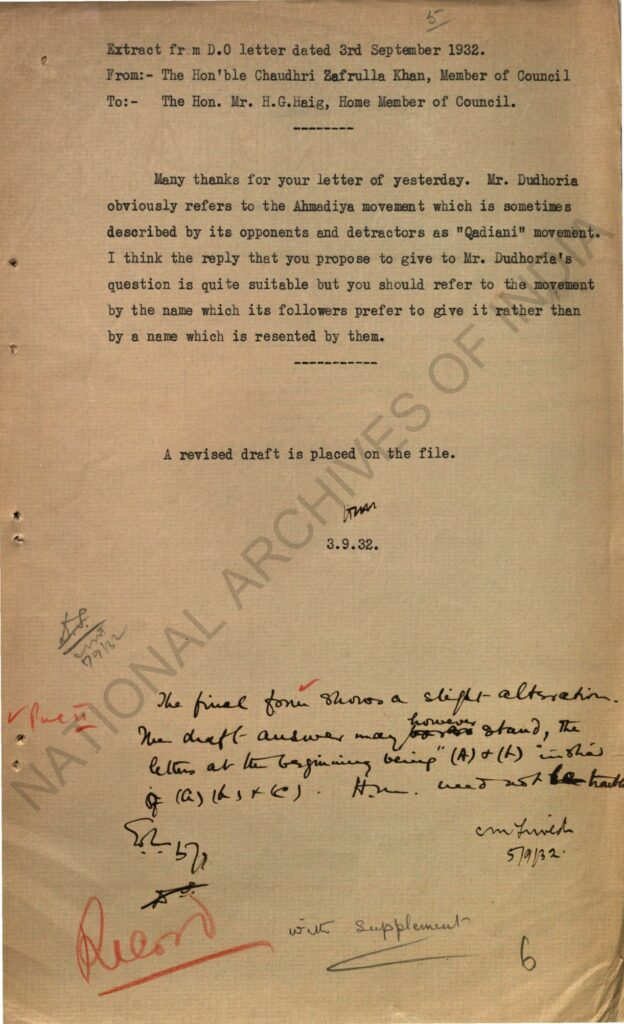

Upon this, Sir Zafrulla Khanra replied as follows:

“Many thanks for your letter of yesterday. Mr. Dudhoria obviously refers to the Ahmadiya movement which is sometimes described by its opponents and detractors as ‘Qadiani’ movement. I think the reply that you propose to give to Mr. Dudhoria’s question is quite suitable but you should refer to the movement by the name which its followers prefer to give it rather than by a name which is resented by them.”23

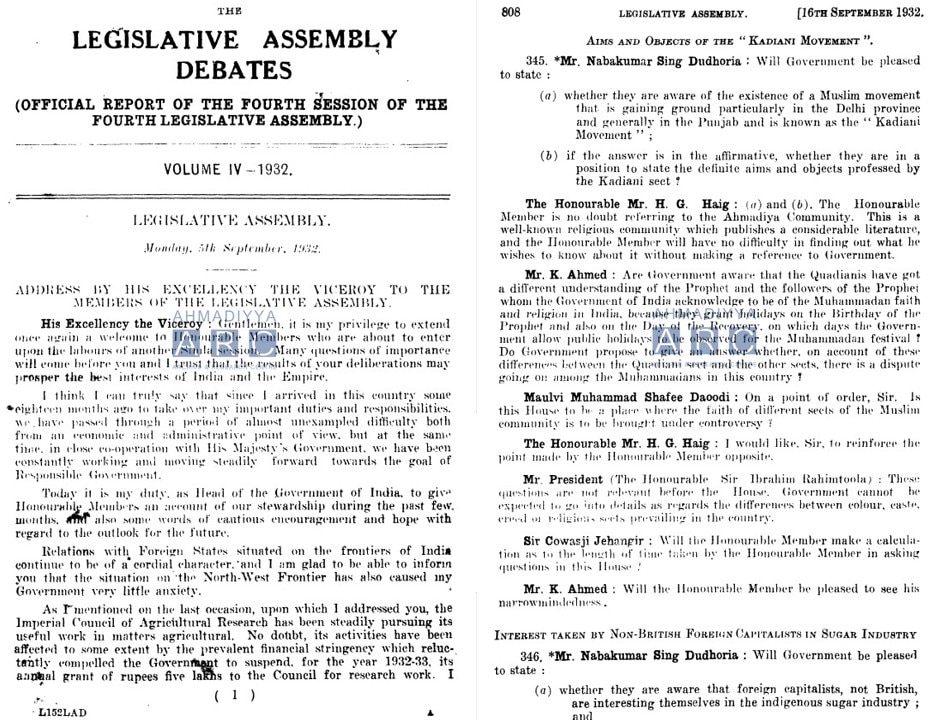

iv) Assembly proceedings, September 1932

Thereafter, it was decided that the question – with some modification – be presented to the Assembly during its 5 September 1932 meeting. The questions were presented in the following words:

“Will Government be pleased to state:

“(a) whether they are aware of the existence of a Muslim movement that is gaining ground particularly in the Delhi province and generally in the Punjab and is known as the ‘Kadiani Movement’;

“(b) if the answer is in the affirmative, whether they are in a position to state the definite aims and objects professed by the Kadiani sect?”24

The question was then answered during the 16 September 1932 session of the Legislative Assembly.

The official records of the Assembly’s proceedings contain very interesting discussion on this matter, which has been titled as “Aims and Objectives of the ‘Kadiani Movement’”.

The transcript of the answers to these questions and the subsequent discussion is as follows:

“The Honourable Mr. H. G. Haig: (a) and (b). The Honourable Member is no doubt referring to the Ahmadiya Community. This is a well-known religious community which publishes a considerable literature, and the Honourable Member will have no difficulty in finding out what he wishes to know about it without making a reference to [the] Government.

“Mr. K. Ahmed [Khabeeruddin Ahmed (1870-1939)]: Are Government aware that the Quadianis have got a different understanding of the Prophet and the followers of the Prophet whom the Government of India acknowledge to be of the Muhammadan faith and religion in India, because they grant holidays on the Birthday of the Prophet and also on the Day of the Recovery, on which days the Government allow Jubilee holidays to be observed for the Muhammadan festival? Do [the] Government propose to give an answer whether, on account of these differences between the Quadiani sect and the other sects, there is a dispute going on among the Muhammadans in this country?

“Maulvi Muhammad Shafee Daoodi [1875-1949]: On a point of order, Sir. Is this House to be a place where the faith of different sects of the Muslim community is to be brought under controversy?

“The Honourable Mr. H. G. Haig: I would like, Sir, to reinforce the point made by the Honourable Member opposite.

“Mr. President (The Honourable Sir Ibrahim Rahimtoola) [1862-1942]: These questions are not relevant before the House. [The] Government cannot be expected to go into details as regards the differences between colour, caste, creed or religious sects prevailing in the country.

“Sir Cowasji Jehangir [1879-1962]: Will the Honourable Member make a calculation as to the length of time taken by the Honourable Member in asking questions in this House?

“Mr. K. Ahmed: Will the Honourable Member be pleased to see his narrow-mindedness?”25

1935: KL Gauba and the Punjab Legislative Assembly

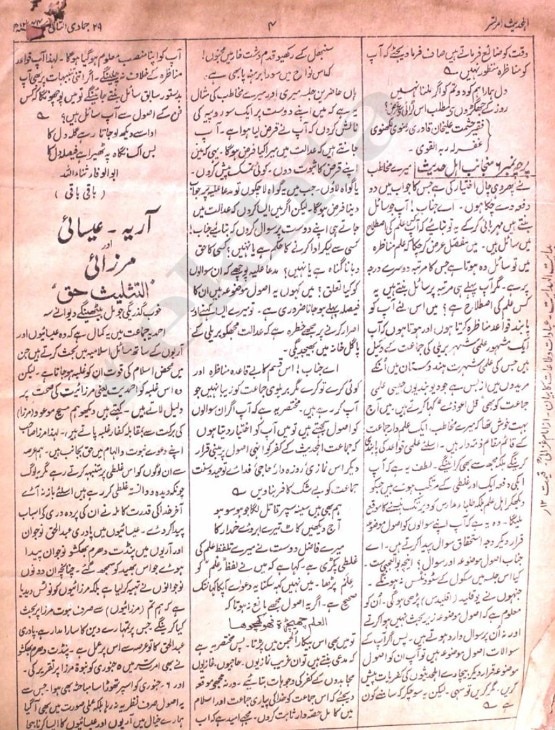

Such attempts were made in the following years as well. For instance, Mr KL Gauba, who had converted to Islam in 1933 and was a member of the Punjab Legislative Assembly, raised false allegations against the Promised Messiahas and stated that, God forbid, he had disrespected the non-Ahmadi Muslims by using abusive language.

Mr Gauba proposed to put the question in the Assembly whether the government was aware that the Founder of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community has, God-forbid, used “abusive” language against other Muslims.

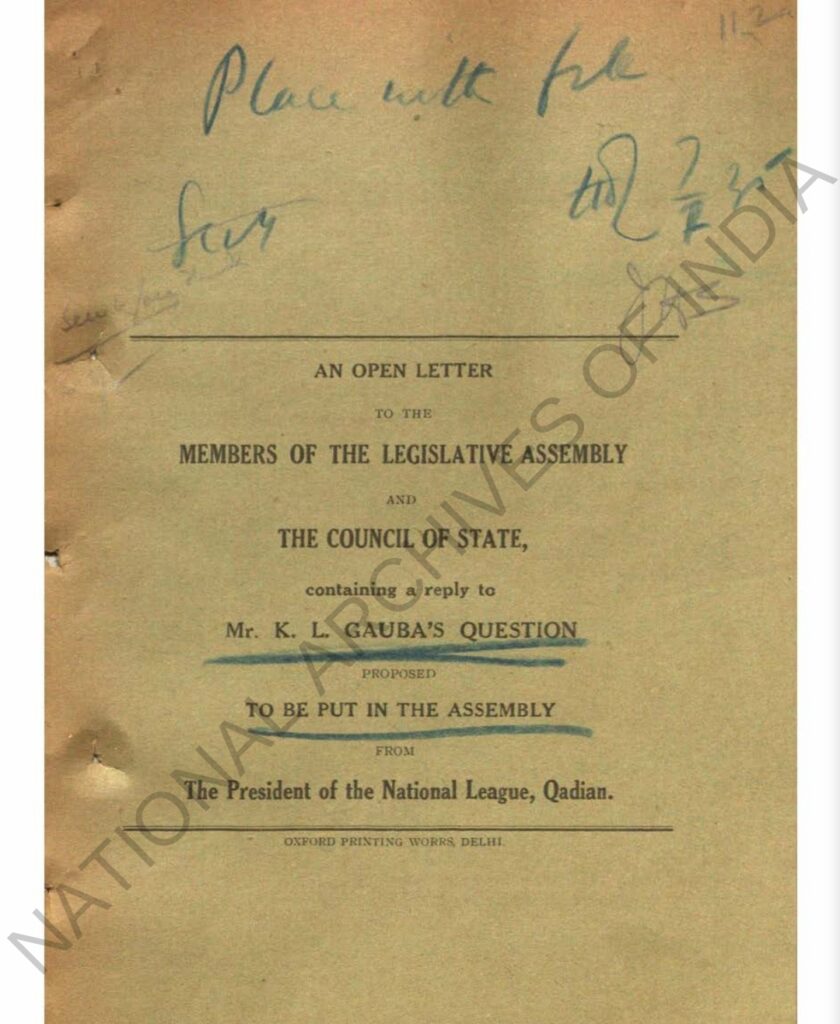

Considering the possibility of it being presented to the Assembly, “An Open Letter” was published from Qadian to refute Mr Gauba’s false allegation. It was titled “An Open Letter to the Members of the Legislative Assembly and the Council of State Containing a Reply to Mr. K. L. Gauba’s Question”. It was published in the March 1935 issue of The Review of Religions as well.

However, later on, KL Gauba’s proposal for the question about the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat was disallowed.

It is important to mention that KL Gauba had strong ties with the Ahrar and in the 1934 general elections, he contested as an Ahrar nominee.26

Mr Gauba would openly express his support for the Ahrar and his views about Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya. For instance, he once said:

“If the Government genuinely wants Muslim friendship, it must remove the sources of irritation; it must give up its support of the Qadianis. […] However great the task which the Ahrar party has set itself, it has been achieved, Kashmir, Kapurthala, Alwar and now Qadian are milestones in its march of triumph. Its successes lie in the causes that it champions. It is the party of the Muslim masses and the masses regard it as their own.”27

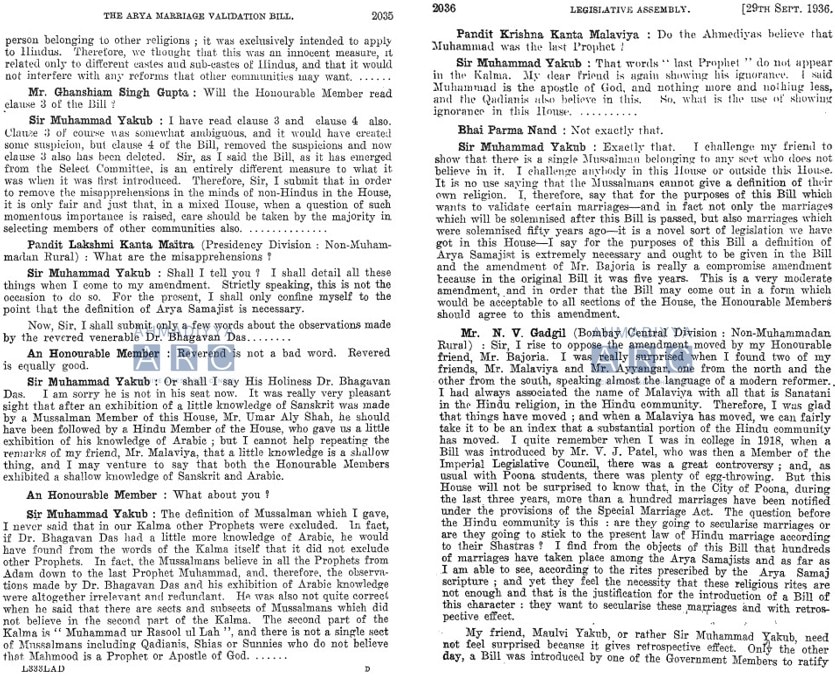

1936: Definition of a Muslim, Kalima and prophethood

Even in 1936, during a debate regarding the communal issues of British India, the Ahmadiyya faith came under discussion. A member of the Central Legislative Assembly, Sir Muhammad Yakub, presented the definition of a Muslim and said:

“The second part of the Kalima is ‘Muhammad ur Rasool ul Lah’ [sic.], and there is not a single sect of Mussalmans including Qadianis, Shias or Sunnies who do not believe that Mahmood [sic.] is a Prophet or Apostle of God.”

Upon this, another member, Pandit Krishna Kanta Malaviya, asked:

“Do the Ahmediyas believe that Muhammad was the last Prophet?”

Sir Muhammad Yakub replied:

“That words ‘last Prophet’ do not appear in the Kalima. Dear friend is again showing his ignorance. I said Muhammad is the apostle of God, and nothing more and nothing less, and the Qadianis also believe in this. So, what is the use of showing ignorance in this House.”28

Conclusion

In summary, debates about the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community’s faith in British India’s legislative assemblies reveal prevailing hostility towards Ahmadis and misunderstandings regarding their religious identity.

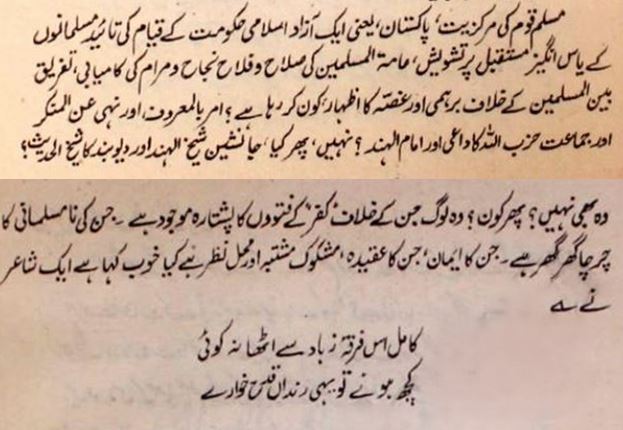

A well-known journalist of British India, Raees Ahmad Jafri (1908-1968), had beautifully summarised the bitter reality that the same community that showed concern for the future of Muslims and strived for their rights, was being made subject to the edicts of kufr.

Jafri wrote that the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, despite being at the forefront of serving Islam, is a community “against whom there is a knapsack of the edicts of ‘kufr’, whose non-Muslimness is talked about everywhere, [and] whose faith and belief is considered to be doubtful, suspicious and objectionable.”29

During the above-mentioned discussions at the legislative assemblies, while some officials recognised the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat’s faith in Islam, others questioned or marginalised them, foreshadowing later persecution, such as the Parliament of Pakistan declaring Ahmadis as non-Muslims in 1974. This was followed by further restrictions and stricter laws in Pakistan.

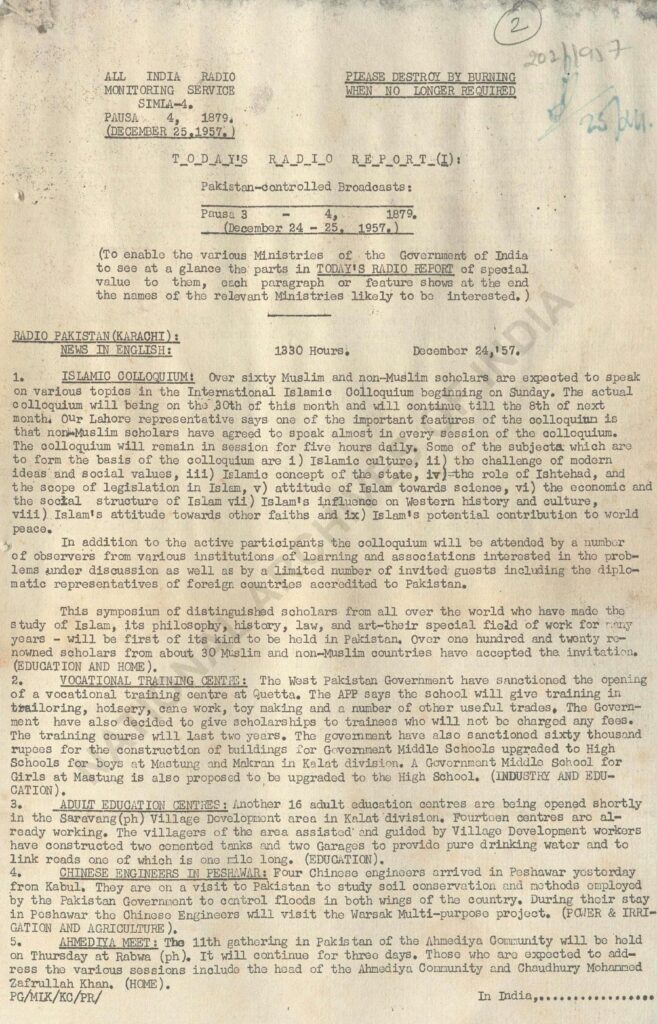

There was a time when the Radio Pakistan would give news about the Jalsa Salana of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jamaat in Pakistan, for instance Radio Pakistan (Karachi) made an announcement about the 1957 Jalsa Salana Rabwah (see the scan below), but now the Ahmadis in Pakistan are not even allowed to hold such gatherings.

Endnotes

1. “The Ahmadi Muslims of Pakistan: A loyal community under siege since 1974”, alhakam.org , 7 September 2024

2. Shuddhi Movement In India: A Study of its Socio-political Dimensions, RK Ghai, [ed. 1990], p. 97

3. Al Fazl, 1 September 1925, p. 8

4. Nur-i-Afshan, 14 August 1925

5. Nur-i-Afshan, 21 August 1925, p. 7

6. Ahl-i-Hadith, 15 January 1926, p. 4

7. Ibid.

8. National Archives of India, “Alleged ill-treatment of Indians in Siam”, Political, File No. 212, 1925

9. Ibid.

10. Hayat-i-Shibli [ed. 1970], p. 571

11. The Times of India, 5 July 1930, p. 11

12. The Civil and Military Gazette, 14 December 1937, p. 10

13. Times of India, 22 April 1935

14. The Civil and Military Gazette, 2 July 1935, p. 13

15. The Civil and Military Gazette, 22 September 1934

16. Yaran-e-Kuhn, Abdul Majeed Salik, Matbu‘at-e-Chitan, pp. 87-88

17. Karwan-e-Ahrar, Vol. 2, Maktaba Tabsarah Lahore, 1977, pp. 79-80

18. Ibid., p. 80

19. National Archives of India, Government of India, Home Department, Political Section, File 30/132

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid.

25. The Legislative Assembly Debates (Official Report), Vol. IV, 1932, Government of India Press, New Delhi, 1933, p. 808

26. Tarikh-e-Ahrar, p. 198; Karwan-e-Ahrar, Vol. 2, pp. 94-95

27. The Civil and Military Gazette, 16 May 1935, p. 7

28. The Legislative Assembly Debates (Official Report), Vol. VIII, 1936, Government of India Press, New Delhi, 1933, pp. 2035-2036

29. Quaid-e-Azam Aur Unka Ehad – Hayat-e-Muhammad Ali Jinnah, pp. 344-346